A Critique Of Scientific American’s Recent Article, “What Are Puberty Blockers, and How Do They Work?”

The stakes are too high for this

What’s Coming Up This Month

If you’re a paying subscriber to this newsletter, THANK YOU. You’re the reason I’m able to write long, in-depth articles like this one. Here’s some of what’s on tap:

The Guardian’s Coverage Of Jordan Neely’s Killing Is Really Quite Bad: This is what happens when journalists act like activists.

The Time I Briefly Grasped The Bottom Millimeter Of The Bottom Rung Of A Famous Humor Publication: A college story, which, like most of my college stories, mostly involves me sitting around and brooding and writing forgettable dreck. Not that different from my adult years, now that I think about it.

It’s Interesting How Much Discretion Courts Have To Decide How To Evaluate Scientific Evidence: What’s more trustworthy: an expert witness’s claim about a scientific controversy, or the conclusions of a carefully conducted systematic evidence review that directly contradicts that expert witness? The answer is obvious in most cases, and yet the American court system hasn’t recognized that. I’ll explain why that’s the case, drawing on some examples from a very sad story involving a debunked treatment for metastatic breast cancer.

Against (Bad Arguments For) Incivility: Let’s overanalyze Alex Goldman’s call for Matt Yglesias to be cyberbullied right off Twitter. It’s a richer subject than it sounds — I promise!

If you’re not a premium subscriber and would like access to all of this, plus more, please consider becoming one.

Throat-Clearing

This post is an in-depth critique of an article about puberty blockers that appeared in Scientific American. It is far from the first media criticism I have published about this subject, and I’ve received some admonition for doing so at a time when Republicans are attempting to ban or severely restrict youth (and even adult) medical transition all over the United States.

To quote a mediocre but prolific writer, “ ‘Why Do You Write About This Rather Than That?’ Is Almost Always A Lazy And Unserious Derailing Tactic.” Almost always — there are exceptions. I’ve had people whose opinions I respect suggest to me I should balance things out a bit and write more about these bans and restrictions, and since I understand where they’re coming from, I want to briefly explain my coverage decisions and future plans on this front.

Sometime in the next couple months I will publish a lengthy piece examining a few of these policies in depth and explaining the serious problems with them. But to be honest, in doing so I’ll partially violate an informal rule that guides this newsletter: I tend to stay away from stories everyone else is already discussing. And the story about these bans could not be getting more attention from national mainstream outlets. Look back at my archives and you will see that in most situations where a story is covered daily by some combination of The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, CBS, NBC, and Vox, I am unlikely to chime in — or if I do chime in, it’s to take a different angle from the bulk of the existing coverage.

You won’t find much commentary about Donald Trump or Ukraine in this newsletter, for example, both because I don’t know much about these subjects and because, in light of the overwhelming quantity of existing coverage, it wouldn’t provide much added value for me to wade into these subjects. My own feelings about Donald Trump (bad guy!) or Ukraine (it is bad that Russia invaded!) don’t really matter that much, and are unlikely to spark added value for my subscribers, unless these stories intersect with one of my areas of interest and knowledge.

For the last almost-decade, one of my main areas of focus has been on bad and overhyped popular science and its impact on society, so that’s the lens through which I write about youth transition (if Donald Trump publishes a p-hacked study on social priming, I promise I will be all over it). There are a lot of journalists better equipped than I am to explain what is going on at the state level, and I’m content to let them do their thing. Again, this has been a pretty consistent policy for me: I also haven’t written a lot about state-level attempts to ban or severely restrict abortion, except here, when the aforementioned intersection occurred.

That said, I did write about the youth gender medicine bans before they got national attention: on May 4, 2020, before the attempted bans ramped up and before most major outlets had caught on that this was going to be a major story, I published “Why The Hard Age Caps On Youth Gender Transition Being Proposed By Conservatives Are A Very Bad Idea.” So it’s not as though my own views on this are unclear.

But I think there are multiple bad things going on at the moment. One of them, surely, is the campaign to restrict and ban these treatments. It’s a terrible way of dealing with the genuine controversy surrounding them. It’s had exactly the effect anyone could have anticipated: there’s been panic (justifiably so, in many cases), a circling of the wagons, and it has become only more difficult to have any sort of careful national conversation about these treatments, free of the increasingly deranging influence of our partisan politics.

Lackluster media coverage of this subject precedes these Republican efforts, though. This has been frustrating me for years. Journalists and pundits are utterly failing to disseminate accurate information about very serious treatments, in some cases straightforwardly misleading their audiences — among them parents trying to make medical decisions for kids who are too young to consent on their own — about vital questions involving mental health and suicide. I believe that this will go down as a major journalistic blunder that will be looked back upon with embarrassment and regret.

So I remain committed to calling out this sort of coverage when I come across it. I don’t see a lot of other journalists doing that. And I’m most likely to call it out when it emanates from respected sources of science news, like Science Vs or Science-Based Medicine. That’s why I’m spending this much time criticizing a single article in Scientific American. These outlets have to do better.

My Critique Of “What Are Puberty Blockers, and How Do They Work?”

Here’s the article. I feel a little bad critiquing it because it was written by a SciAm intern. But it was published in one of the leading science outlets in the world, and it does have some major problems, so I don’t know what to say.

I blame the editors, for whom this is a pattern, far more than I blame the individual author. I’m not going to name her, because I’m not trying to cause long-lasting Google damage to a young journalist’s reputation, but obviously her name will not be hard to find. I promise you, notwithstanding any of the criticisms that follow, that when I was a young journalist I wrote far worse stuff than what she wrote here. She is in a difficult situation, attempting to write about an issue where there is so much spin and so much politicization that it is impossible not to step on landmines unless you are very, very careful. Her editors were not careful. Not at all.

Let’s start here:

Hormonal medications called gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHas), often referred to as puberty blockers, temporarily halt the production of sex hormones testosterone, estrogen and progesterone with minimal side effects. They can pause puberty and buy transgender children and their caregivers time to consider their options.

We don’t know that the side effects are “minimal” when these medications are used on gender dysphoric youth. That’s one of the reasons for controversy, and this language dismisses that controversy in far too pat a manner.

Similarly, the “time to think” line is very much in dispute at this point. Evidence from the Tavistock clinic, in particular, calls it into question because almost every kid there who has gone on blockers has proceeded to hormones. “Time to think” is a common activist line that treats puberty blockers as a common-sense time-buying measure, but that might not be accurate. Many researchers think early puberty can have the effect of resolving gender dysphoria. So it’s an open question, scientifically, whether blockers actually give kids time to think in an otherwise neutral manner, or whether they contribute to the solidification of gender dysphoria by halting a natural developmental process and setting the child along a different pathway. See Hannah Barnes’ book titled, well, Time to Think, or my interview with her, for more information on this.

More:

These medications are well studied and have been used safely since the late 1980s to pause puberty in adolescents with gender dysphoria. They have been used routinely for even longer in children who enter puberty too early and in adults with a range of other medical conditions.

“Since the late 1980s” is technically, narrowly true since the very first gender dysphoric youth had their puberty blocked “around 1987,” as Emily Bazelon put it, but this is quite misleading since (1) the widespread use of blockers for this purpose didn’t catch on until much later, and (2) to this day, we have close to zero studies that have tracked gender dysphoric kids who went on blockers over significant lengths of time to see how they have fared. So it’s absolutely false to claim that these medications are “well studied” in this use case.

As for the second sentence, this gets to a certain confusion that comes up often in this debate — confusion that I think is intentional in some cases. Yes, puberty blockers have been used to treat precocious puberty for longer than they have been used to treat gender dysphoria, and are better-studied in those circumstances. But these are very different situations.

In the latter case, there’s a very good chance (according to the data we have) the child will then proceed to cross-sex hormones, meaning they won’t go through the natal puberty that would otherwise cause their body and brain to develop in a certain way. Can cross-sex hormones provide an equivalent-enough form of development, without any negative consequences to the teenager’s physical or cognitive development? The answer is simply that we don’t know yet, because we have hardly any medium-term data and no long-term data following young people who have gone through this protocol. That’s why you can’t conflate these two use cases. On top of all of that, there are questions about the safety of using puberty blockers to buy time for kids with precocious puberty, too. This goes unmentioned by Scientific American.

You don’t have to trust me that we don’t have good evidence for using puberty blockers to help trans kids. Here is the otherwise very pro-transition World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care 8: “Despite the slowly growing body of evidence supporting the effectiveness of early medical intervention, the number of studies is still low, and there are few outcome studies that follow youth into adulthood. Therefore, a systematic review regarding outcomes of treatment in adolescents is not possible.” I disagree with the first half of that sentence, since many of the recent studies are quite weak and/or offer mixed results (more on that soon), but if WPATH thought there was good, high-quality evidence to support blockers, of course it would have shined a spotlight on it.

Every government-sponsored investigation of the evidence base for puberty blockers has come to the same conclusion: the quality of extant literature is so weak that no one really knows whether they are safe and effective for gender dysphoric youth. The healthcare systems of Finland and Norway have gone so far as to call these treatments “experimental,” as did the Swedish team behind a major, just-published systematic review. The UK’s National Health Service hasn’t quite gone that far, but late last year it proposed new guidelines, based in part on this realization about the evidence base, that would call for a significantly more conservative approach to administering blockers and hormones (again, see Barnes’ book for more background on this).

You would know none of this reading Scientific American’s article about puberty blockers. And frankly, that makes the piece negligent science journalism. Of course the existence of these reviews doesn’t, on its own, resolve the question of exactly what our feelings should be toward these medications, let alone what national or state-level policies toward them should be. Sometimes you have to make healthcare decisions for a vulnerable young person under conditions of scientific uncertainty. But that uncertainty is an absolutely crucial part of the story — a major detail that has to be communicated by journalists writing about this subject.

It’s baffling and frustrating that, in 2023, the magazine’s editors are comfortable allowing their publication to claim both that there’s solid evidence puberty blockers help gender dysphoric kids, and to conflate two such different uses for this medicine. This is an extremely misleading, potentially harmful claim to disseminate to parents trying to work through an extremely fraught medical decision.

The article then notes that “Half of transgender people aged 13 to 24 have seriously considered suicide in the past year, according to a 2023 nationwide survey released on May 1 by the Trevor Project, a nonprofit focused on LGBTQ+ suicide prevention.”

This is one of the more subtle critiques I’m going to level at this article, but I think it’s important, because it gets at one of the worst types of misleading assertion about youth gender medicine: claims involving suicide.

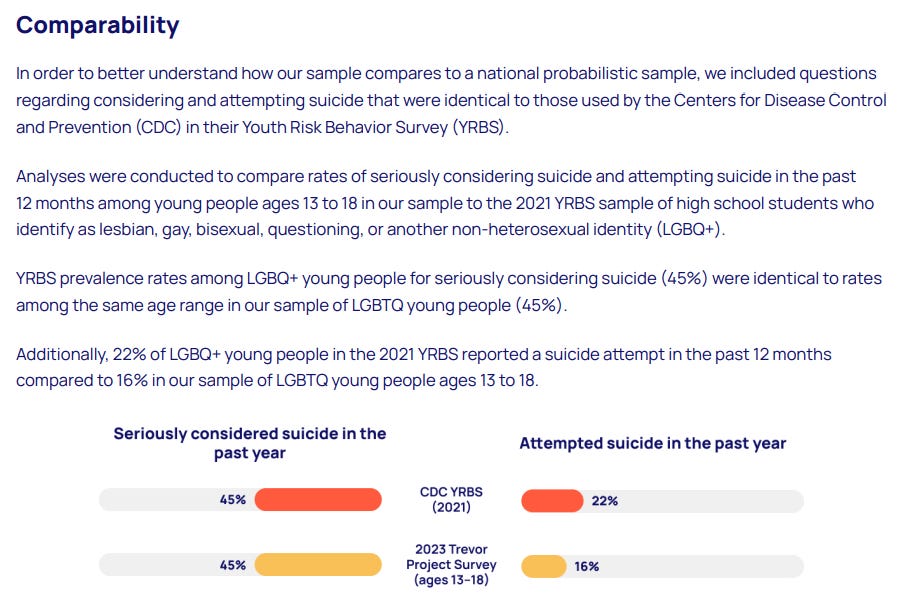

It’s true that the Trevor Project asked its respondents whether they had attempted or considered suicide in the past year, and that responses were alarmingly high. In its write-up of the survey, the organization touts that it got similar numbers as a more representative sample: the teen LGBT subset of respondents to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS):

Luckily, these are almost certainly significant overestimates of the prevalence of serious suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among the LGBT population. Or at least that’s what suicide researchers think. This paragraph from a Williams Institute report entitled “Suicide Attempts among Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Adults: Findings of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey,” which found that an astonishing 41% of trans respondents reported having ever attempted suicide, is very useful:

While the NTDS provides a wealth of information about the experiences of transgender and gender non-conforming people, the survey instrument and methodology posed some limitations for this study. First, the NTDS questionnaire included only a single item about suicidal behavior that asked, “Have you ever attempted suicide?” with dichotomized responses of Yes/No. Researchers have found that using this question alone in surveys can inflate the percentage of affirmative responses, since some respondents may use it to communicate self-harm behavior that is not a “suicide attempt,” such as seriously considering suicide, planning for suicide, or engaging in self-harm behavior without the intent to die (Bongiovi-Garcia et al., 2009). The National Comorbity [sic] Survey, a nationally representative survey, found that probing for intent to die through in-person interviews reduced the prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts from 4.6 percent to 2.7 percent of the adult sample (Kessler et al., 1999; Nock & Kessler, 2006). Without such probes, we were unable to determine the extent to which the 41 percent of NTDS participants who reported ever attempting suicide may overestimate the actual prevalence of attempts in the sample. [links to other studies added]

I believe the same logic applies to simply asking someone if they have “seriously considered suicide” without any follow-up probes. This is part of a broader phenomenon often observed in opinion polling in which respondents endorse extreme sentiments at seemingly alarming rates, unless and until you get more specific with your follow-up questions. The “Lizardman’s constant” is the most extreme (and entertaining) example of this.

Trans youth can experience heightened risks of suicidality, but these numbers are frequently presented in a scaremongering, exaggerated manner. Better, more careful means of measuring suicidality, such as with the use of validated tools in clinical contexts, yield different and somewhat less dire results.

As the Australian psychiatrist Alison Clayton, who is affiliated with the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine, a group that is skeptical of youth gender medicine, explained in an excellent recent article in Archives of Sexual Behavior:

[T]he suicidality of GD youth presenting at [child and adolescent gender clinics], while markedly higher than non-referred samples, has been reported to be relatively similar to that of youth referred to generic child and adolescent mental health services (Carmichael, 2017; de Graaf et al., 2022; Levine et al., 2022). A recent study reported that 13.4% of one large gender clinic’s referrals were assessed as high suicide risk (Dahlgren Allen et al., 2021). This is much less than conveyed by the often cited 50% suicide attempt figure for trans youth (Tollit et al., 2019). A recent analysis found that, although higher than population rates, transgender youth suicide (at England’s CAGS) was still rare, at an estimated 0.03% (Biggs, 2022).

Here and there, such as at this Belgian clinic and in a study we’ll get to shortly, fairly alarming rates of suicidality and suicide are observed (there are actually almost no studies of trans youth measuring completed suicide), but context is quite important here: Even if you cherry-pick the scariest research, there’s no reason to think that 40% or 50% of trans youth are at a serious risk of killing themselves.

It’s unfortunate that the discourse surrounding youth gender medicine often claims otherwise, because the constant dissemination of the meme “huge numbers of trans kids will kill themselves if they don’t have ready access to blockers or hormones” both incites unnecessary fear and could potentially contribute to suicide contagion. That’s why experts implore journalists and others to be very, very careful when publishing about this subject. The Scientific American article is (very) far from the worst offender, but it exemplifies a common problem that could exacerbate the risk to trans kids.

After mentioning trans kids’ scarily high risk of suicide, the article continues:

Gender-affirming hormone therapy can decrease this risk. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, showed that hormone therapy significantly decreased symptoms of depression and anxiety in transgender youth. Another study found that transgender teenagers who received gender-affirming care were 73 percent less likely to self-harm or have suicidal thoughts than those who didn’t.

Imagine a pillar of frowny faces ten thousand light-years high.

It is really, really frustrating that SciAm is spreading these messages. Remarkably, not only do neither of the linked-to articles in this passage demonstrate a reduction in suicidality (which is distinct from depression and anxiety) among kids who went on blockers or hormones, but there’s a case to be made that both findings offer some evidence these treatments don’t reduce suicidality.

If you’re a regular reader, we’ve been over this before. Let’s start with the NEJM study, which was published by an all-star team of gender clinicians as part of a very ambitious, federally funded ongoing research effort. As I’ve noted previously, Diane Chen et al.’s study failed to report on six of the eight variables the authors mentioned in their primary, preregistered hypothesis, including suicidality — which strongly suggests they didn’t find what they wanted to find. And while the cherry-picked variables that were reported did include anxiety and depression, these findings weren’t promising, either: there was no statistically significant improvement for trans girls (natal males) on either front, and the overall average decreases (the researchers didn’t provide specific numbers by natal sex) were of questionable clinical importance: over the course of two years, depression decreased just 2.54 out of 63 points, while anxiety decreased just 2.92 out of 100 points. On top of all of that, because the researchers didn’t control for access to medication or therapy, there’s genuinely no reason to attribute these improvements to hormones rather than those factors, the placebo effect, other influences, or a combination of all or some of the above. Any experienced, critical reader of this sort of research should come away from the NEJM study thoroughly unconvinced the authors have established the causality they claim to have established when they write that hormones “improved appearance congruence and psychosocial functioning.” (I remain surprised NEJM allowed this language to slip through into the paper, given that the authors ticked basically zero of the boxes required to make such a claim. It isn’t a close call.)

As for suicides, the authors note that there were two completed suicides in a sample of 315 kids. While (as I noted in my original write-up) one needs to interpret a rate based on a small number of raw events with caution, this is undeniably a high rate, especially when you account for the fact that this sample was screened, at the outset of the study, for severe psychological problems, including suicidality.

So:

The authors of a major study, in their preregistered protocol, say they’re going to measure suicidality in a sample of kids who go on hormones.

They mysteriously fail to report anything about that variable, other than to note, almost as an aside, that there were two completed suicides — meaning the sample had a high rate of suicide. Several other key variables are missing as well, with no explanation.

In short, the study provides no evidence that, in this sample of trans youth, access to hormones reduced suicidality.

Scientific American points to this study as evidence that hormones reduce suicidality in trans youth.

You can see how this is frustrating, right? You can see why I keep writing these articles?

As for SciAm article’s claim that “Another study found that transgender teenagers who received gender-affirming care were 73 percent less likely to self-harm or have suicidal thoughts than those who didn’t,” it’s simply remarkable that this zombie study is still shambling along in 2023. Again, we’ve been over this: Diana Tordoff and her colleagues found no sign that the kids they followed who went on blockers and hormones (again, no controlling for medication or therapy) experienced improved mental health outcomes over time. Then they went ahead and claimed the opposite.

How were they able to pull off this feat? First, they used a very weird statistical technique, which was described to me as “quite a poor person’s way of dealing with [this sort of data]” by James Hanley, the statistician who coauthored what I believe to be the most-cited article about that technique. They also ignored the fact that 80% of the non-treatment group had dropped out by the end of the study, leaving just six kids, as compared to a much smaller percentage for the treatment group, meaning it’s more or less impossible to draw any meaningful comparison between the two groups.

See my post for the grisly details, but the point is that no informed, good-faith person familiar with the taped-and-Elmer’s-glued-together nature of this study could possibly claim that it found “transgender teenagers who received gender-affirming care were 73 percent less likely to self-harm or have suicidal thoughts than those who didn’t” — at least not without a hell of a lot of hedging and throat-clearing — and I will happily repeat myself by arguing that it is immoral to disseminate this sort of claim in this sort of context.

It would not be difficult for Scientific American to be a bit more skeptical about. . . well, all of this. But I think the same thing is going on here that went on with Science Vs: because these claims about blockers and hormones are seen as politically urgent, certain critical faculties get switched off in service of the seemingly noble goal of spreading the word. SciAm would never exhibit this level of credulousness toward a conservative-coded scientific claim.

Moving on:

Puberty has a long natural window, which typically occurs between eight and 14 years of age and lasts from two to five years. Blockers are usually prescribed once puberty has already begun, and the process involves evaluations by multiple doctors, including mental health practitioners, explains Stephen Rosenthal, a member of the board of directors at the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and a pediatric endocrinologist at the University of California, San Francisco, Benioff Children’s Hospitals.

If you’re going to get Rosenthal, a coauthor on that NEJM study, on the phone, why not ask him what happened to those six missing variables? It seems like a missed opportunity.

Anyway, Scientific American is seriously oversimplifying things here. The protocol American youth gender clinicians use is more or less descended from something known as the “Dutch protocol” (I’m excited that this book just arrived), which originated at a world-famous (to nerds) Amsterdam gender clinic, and entailed very careful, thorough assessments. Under this protocol, kids were seen for months, and carefully evaluated for psychological comorbidities, before they were allowed to go on blockers or hormones, or to (later on) get surgery.

I don’t know if things have since loosened up a little over there, but traditionally, kids simply were not allowed to transition if their other mental health issues weren’t under control, if they didn’t have supportive parents, or if they didn’t have a long-standing history of childhood gender dysphoria. Some of the only decent research we have comes from this very specific clinical context, though even that research isn’t as straightforward as many (myself included) have previously assumed, at least according to this article by Oxford sociologist Michael Biggs and this critique by E. Abbruzzese, Stephen Levine, and Julia Mason.

Stephen Rosenthal is describing a process that sounds Dutch-ish. Is that what’s going on in American gender clinics? Probably not, at least in many cases. Here’s Reuters last year:

In interviews with Reuters, doctors and other staff at 18 gender clinics across the country described their processes for evaluating patients. None described anything like the months-long assessments [leading Dutch clinician Annelou] de Vries and her colleagues adopted in their research.

At most of the clinics, a team of professionals — typically a social worker, a psychologist and a doctor specializing in adolescent medicine or endocrinology — initially meets with the parents and child for two hours or more to get to know the family, their medical history and their goals for treatment. They also discuss the benefits and risks of treatment options. Seven of the clinics said that if they don’t see any red flags and the child and parents are in agreement, they are comfortable prescribing puberty blockers or hormones based on the first visit, depending on the age of the child.

On top of that, many of the kids coming to gender clinics today don’t have a history of childhood gender dysphoria, which means they wouldn’t have been eligible for transition under the Dutch protocol, and which also means any honest clinician would have to concede that there’s significantly less evidence to support putting them on blockers and/or hormones.

De Vries herself raised some concerns about this in Pediatrics in 2020:

According to the original Dutch protocol, one of the criteria to start puberty suppression was “a presence of gender dysphoria from early childhood on.” Prospective follow-up studies evaluating these Dutch transgender adolescents showed improved psychological functioning. However, authors of case histories and a parent-report study warrant that gender identity development is diverse, and a new developmental pathway is proposed involving youth with postpuberty adolescent-onset transgender histories. These youth did not yet participate in the early evaluation studies. This raises the question whether the positive outcomes of early medical interventions also apply to adolescents who more recently present in overwhelming large numbers for transgender care, including those that come at an older age, possibly without a childhood history of GI. It also asks for caution because some case histories illustrate the complexities that may be associated with later-presenting transgender adolescents and describe that some eventually detransition. [footnotes omitted]

I don’t think anyone who reads SciAm’s description of a carefully conducted evaluation process will know that 1) this clearly isn’t happening in many American gender clinics, 2) many of the kids showing up at these clinics are nothing like their Dutch predecessors, meaning some of the little bit of research we have can’t be applied to them, and 3) one of the leaders of the Dutch clinic took to the pages of Pediatrics to express her concerns about treating this new cohort.

It’s baffling and frustrating that, in 2023, Scientific American’s editors are comfortable leaving so much. . . stuff out of a complicated story, opting instead for a breezy, oversimplified account.

The article also originally stated that “The World Professional Association for Transgender Health’s standards of care recommend waiting until adulthood for gender-affirming surgeries,” which is not true. The document SciAm originally linked to here, a WPATH Frequently Asked Questions about its most recently released standards of care, indeed claimed:

The SOC-8 guidelines recommend that patients reach the age of adulthood, which may vary based on where that TGD person lives or is seeking care, to be a candidate for gender-affirming surgery. These guidelines are designed to help providers make individualized assessments about when and for whom a procedure is age-appropriate and medically necessary and exist to ensure that patients receive the individualized care they need, as is true across medicine.

This is going to sound weird but the WPATH is. . . misstating its own guidelines. In fact, hours after the SOC 8 was released, a “correction” was issued that stripped out all guidelines about ages. The actual, operative version of the SOC 8, then, does not include age restrictions. At the time, this caused a bit of a blowup because some people, like Ron DeSantis’s deputy press secretary, noticed the change and expressed their outrage.

https://twitter.com/JeremyRedfernFL/status/1570916264918536195

This sentence jumped out at me the same way it would to anyone who has been following this issue, because the removal of age restrictions was seen as a pretty big deal at the time. I emailed the editor-in-chief of Scientific American to ask about this and, to her credit, the text has since been updated and now links to the actual SOC 8 rather than that weird FAQ (though the change is noted at the bottom rather than in-text, which is a pet peeve of mine because hardly anyone reads an article all the way to the very bottom). But I can’t resist pointing out that this is an error that could really only have occurred if everyone involved in the process of publishing this article was quite unfamiliar with the contours of this debate and how it has evolved in recent years. (I also emailed WPATH to double-check, and I got back a statement from Marci Bowers, president of WPATH, confirming the absence of age requirements, that I’ll stick in a footnote.1)

After SciAm reiterates that puberty blockers have been used to treat other conditions over the years, the article continues with some more breezy oversimplifications:

This host of beneficial clinical uses and data, stretching back to the 1960s, shows that puberty blockers are not an experimental treatment, as they are sometimes mischaracterized, says Simona Giordano, a bioethicist at the University of Manchester in England. Among patients who have received the treatment, studies have documented vanishingly small regret rates and minimal side effects, as well as benefits to mental and social health.

The timeline here is simply inaccurate. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone wasn’t discovered until 1971, and wasn’t first used to treat precocious puberty until a decade later. This is another instance of SciAm linking to a document that says something is true and taking that as gospel. The link on “back to the 1960s” indeed points to a paper that argues that “Puberty blockers have been in use for delaying early (precocious) puberty in children since the 1960s,” but the citation at the end of that sentence makes no such claim. I myself am not all that familiar with this history, and this would have slipped by me unnoticed if someone else hadn’t pointed it out to me, but again. . . this is Scientific American. If they can’t get basic questions like “When was this hormone discovered?” right, it should call a lot of things into question. (Immediate post-publication addition that I meant to include: I emailed the EIC about this as well, but I hadn’t heard back yet by the time I published this article about 20 hours later. It’s a weekend and a relatively minor issue that I described as “[d]efinitely not urgent” in my email, so I wouldn’t have expected her to address it immediately.)

Timeline issues notwithstanding, this is the same bit of elision we saw before. Whether puberty blockers are an “experimental treatment” for other conditions is a completely different question from whether they are an “experimental treatment” for youth gender dysphoria. The fact is we have almost no quality evidence addressing puberty blockers’ safety and efficacy in the latter setting. Why is Scientific American hiding all of this from its readers?

As for the claim about “vanishingly small regret rates,” it’s unwarranted and leaves out a lot of context. The claim links to a single study from a Dutch clinic that engaged in a careful diagnostic evaluation of all its patients prior to putting them on blockers. “This evaluation usually consisted of approximately six visits (more if necessary) of the adolescent with an MHP in 6–12 months in addition to interviews with parents/guardians.” Among these carefully selected kids, 3.5% regretted going on puberty blockers, and a handful of others discontinued the blockers for health reasons, though that group mostly later proceeded with gender-affirming medicine one way or another.

It’s good that the rate is low, but what would that figure be if these kids hadn’t been carefully assessed? If they’d gone on blockers after a single visit to a clinic? If they hadn’t had the benefits of the Dutch rather than the American healthcare system? We have no studies about puberty blocker regret or discontinuation rates in an American context. So to say these treatments have “vanishingly small regret rates” on the basis of a single study from a single foreign clinic that takes a much more gatekeeper-y approach than what appears to be going on in the States is disingenuous. It’s a very basic principle of science writing and editing that you can’t over-extrapolate from most single studies, and surely Scientific American’s editors are well-acquainted with it.

Let’s zoom through the two other links from this paragraph:

minimal side effects — The linked-to editorial doesn’t argue that puberty blockers have “minimal side effects,” but rather that there are unknown medium- and long-term side effects, but they shouldn’t be seen as sufficient evidence to deem the treatments “experimental.” The authors themselves argue that “The questions that still need answering are about the medium- and long-term effects of puberty delay,” and that “If it can be substantiated in larger studies that peak bone mass is affected by GnRHa treatment it will obviously become an important consideration in the general risk/benefit calculation prior to offering this treatment.” It is simply inaccurate to present this article — which is an editorial, anyway, rather than a research paper or review or meta-analysis — as evidence that blockers have “minimal side effects,” because the authors themselves don’t even make that claim!

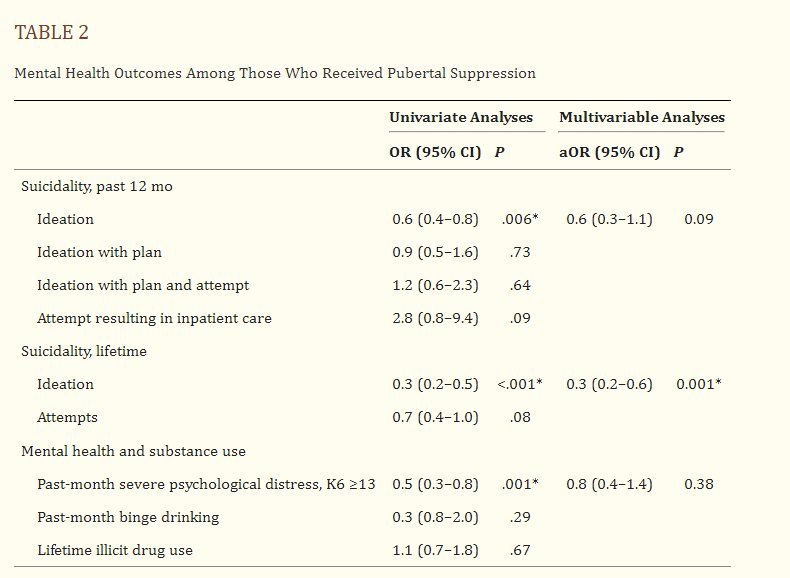

mental and social health — This links to one of Jack Turban and his team’s studies. It is, to phrase things bluntly, not serious research. It relies on a broken self-report data set known as the 2015 United States Transgender Survey that, among other problems, excludes detransitioners —click here and scroll down to “There are many reasons to be skeptical” if you are unfamiliar with why work based on the USTS often isn’t to be trusted. To interpret this data the way Scientific American is also neglects the possibility that poor mental health causes a lack of access to transition care rather than vice versa (because some clinicians and medical guidelines view solid mental health as a prerequisite to blockers or hormones). On top of that, the researchers found only one statistically significant correlation, out of three, in their most well-controlled model. By their own methodology and argument, in this model access to blockers had no statistically significant impact on past-month severe psychological distress or past-year suicidal ideation. Even in their simpler, so-called “univariate model” (meaning a model that does not control for other, potentially confounding variables), there was no correlation between access to blockers and more serious forms of recent suicidal ideation.

If blockers are as wonderful and effective as advocates say, why would all of this be the case?

See Michael Biggs’ letter here for a thorough yet concise debunking of this study. Nobody should be making decisions about a child’s or teenager’s healthcare on the basis of this sort of research, and to be clear, my argument is that we probably can’t draw any strong conclusions from any research published on the basis of the 2015 USTS.

More broadly, even if the dataset were less broken, you just can’t make causal determinations about whether a medical treatment works through this sort of survey research — too many things can go wrong. It would be hard to come up with a less compelling type of medical evidence, given what we know about the difference between good and bad medical research.

On the other hand, Jack Turban himself thinks the Scientific American article that cited his work is good, so maybe I’m incorrect?

Joking aside, it’s baffling and frustrating that, in 2023, Scientific American’s editors are comfortable publishing such misleading arguments, are so unfamiliar with the many critiques leveled against a study first published more than three years ago, and are completely unwilling to engage with any of them. It’s not very. . . scientific.

Last one: “Meanwhile the increased rates of suicide among those who do not receive gender-affirming care is well documented.”

This really drives me crazy.

Now we’ve moved on from assertions about suicidal ideation and attempts to claims about completed suicides. It would be hard to come up with a more serious claim than “If you don’t give your kid this medication, you are increasing the probability that they will commit suicide,” and as regular readers will know from this article I wrote responding to Science Vs’s version of this argument, it is not borne out by the evidence. It’s an irresponsible thing to tell parents — or kids or teenagers considering youth gender medicine, for that matter.

Let’s go through the two links:

well — This links to a MedPage article headlined, ridiculously, “Gender-Affirming Meds Have Drastic Impact on Suicide Risk in Trans Youth.” It’s paywalled but shhhhh, and if you click that link you’ll see that it’s a favorable write-up of. . . the Tordoff study. The Tordoff study didn’t measure completed suicide. I sincerely hope no one in their cohort killed themself, but if they did, the researchers haven’t seen fit to inform us of that fact. So setting aside the many other problems with this study, you simply can’t point to it as evidence that if you deny kids access to youth gender medicine, their suicide rate goes up.

documented — This points to a Time magazine article about a study based on survey data from the Trevor Project. Again, SciAm is confusing itself (and its readers) by mixing up suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides, which are crucial distinctions for researchers in this area. Obviously, a survey study cannot tell us anything about completed suicides. But going beyond that simple observation, this study was structured similarly to some of Turban and his team’s work — it compares those who reported having ever received hormones to those who reported wanting them but not having received them — and suffers from the same major obstacles to establishing any sort of causality. Again, the data could be partly explained by the exact opposite of what is being claimed: being mentally ill made young people less likely to be able to access hormones.

The Scientific American article also talks about some bone health stuff I’m less familiar with, so I can’t speak to its quality without doing some reporting I don’t have time to do right now, but in light of the above. . . let’s just say that my default stance would be skepticism. I would not take anything in this article at face value, without vigorous fact-checking — the fact-checking that should have occurred before the article was published.

So I’ll leave things here. It seems an appropriate note to end on: a major science magazine makes a very serious claim about suicide — that a specific intervention is “well established” as reducing it. That phrase links to write-ups of two studies, neither of which even measured completed suicide, let alone proved that the intervention in question reduces its likelihood. That’s where mainstream science reporting is on all this.

It’s pretty bad, guys. The good news is that since it’s very clear what has gone wrong, there’s no reason these outlets can’t do better.

Right?

Questions? Comments? Demands I focus on that, not this? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com. Image:“Signs are seen as LGBTQ activists protest on March 17, 2023, in front of the US Consulate in Montreal, Canada, calling for transgender and non-binary people be admitted into Canada. - According to police services, some 200 people gathered in the rain to show support for the trans community in the United States. (Photo by ANDREJ IVANOV / AFP) (Photo by ANDREJ IVANOV/AFP via Getty Images)”

“Throughout the process of developing and updating the Standards of Care 8, we made adjustments to ensure there was consensus among the scientific and medical community based on the latest research. Instead of specifying rigid age limits for certain forms of health care, the SOC-8 provides a detailed framework to help providers assess the needs of patients at different stages of life. We do not want guidance around age-appropriate care to be misinterpreted as being so rigid that patients aren’t able to get care that meets their unique needs. We want to ensure every transgender person receives the age-appropriate and individualized care that is best for them.”

For what it’s worth, I’m not sure it’s accurate to say that there is a “consensus among the scientific and medical community based on the latest research” that there should be no age guidelines dictating the pace of youth gender medicine — in my opinion, there is more evidence to support the idea that activist pressure caused this last-minute edit. Emily Bazelon’s article has good background on the tension within WPATH over questions of assessment and timelines.

“Gender-affirming surgeries are not common among those under age 18 and are usually limited to “‘top surgery,’ or a mastectomy. Breast reduction surgery is also one of the most common forms of plastic surgery in cisgender teenagers.”

I have no words. This is so disingenuous and absolutely NOT comparable.

Thank you, Jesse! Here is a relevant story to this regrettable chapter on the state of gender science in America today:

When the New York Times published the article "They Paused Puberty, but Is There a Cost?" (https://nyti.ms/42pM5ak) on Nov. 14, 2022, one of the letters they received was from Marc B. Garnick from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (https://bit.ly/3VHHtKn), and more importantly, one of three academic principal clinical investigators of studies that led to the initial F.D.A. approval of Lupron [the puberty blocker drug that gets used most often] for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Yes, for metastatic prostate cancer. That letter (see https://nyti.ms/3nwblwJ), published two weeks later on Nov. 28, 2022, said this (and I will quote it in full for those who might not have access behind the paywall): "As one of three academic principal clinical investigators of studies that led to the initial F.D.A. approval of Lupron for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer — and having studied this class of drugs, which includes puberty blockers, for more than four decades — I can say that physicians are still learning and continue to be concerned about the safety of these agents in adults. Woefully little safety data are available for the likely more vulnerable younger population. Bone loss in adult men who have been on these agents is significant [Jesse, you mentioned this topic in your article - that you were less familiar with - it turns out that the concerns you heard were true], and a leading cause of morbidity with long-term administration. Other safety issues include cognitive, metabolic and cardiovascular effects, still under intense investigation. The prudent and ethical use of such agents in the younger population should demand that every pubertal or pre-pubertal child be part of rigorous clinical research studies that evaluate both the short-term and longer-term effects of these agents to better define the true risks and benefits rather than relying on anecdotal information."

So opines the principal investigator of the drug. Need we say more?