How Science-Based Medicine Botched Its Coverage Of The Youth Gender Medicine Debate

The site fell into an all-too-familiar trap

I’m making this post free for everyone, but if you find it useful please consider subscribing to the paid version of Singal-Minded, or giving a gift subscription to a friend. Subscribers get at least seven exclusive articles per month, starting at just $4 per month. My paid subscribers are the reason I was able to take the time to write this in-depth critique, and I’m very grateful for their support.

Science-Based Medicine is a well-established, highly regarded website dedicated to delivering readers information about, well, science-based medicine. It’s run by Steven Novella, a clinical neurologist at Yale University and the site’s founder and executive editor, and David Gorski, a surgical oncologist at Wayne State University and the managing editor.

The About page reads, in part:

Science-Based Medicine is dedicated to evaluating medical treatments and products of interest to the public in a scientific light, and promoting the highest standards and traditions of science in health care. Online information about alternative medicine is overwhelmingly credulous and uncritical, and even mainstream media and some medical schools have bought into the hype and failed to ask the hard questions.

We provide a much needed “alternative” perspective — the scientific perspective.

Novella has long sought to emphasize a distinction between evidence-based and science-based medicine, and that distinction appears to be one of the animating principles of his website. Writing in Skeptical Inquirer in 2015, he explained that “The core weakness of evidence-based medicine is that it relies, as the name implies, solely on clinical evidence to determine whether a treatment is appropriate or not. This may superficially sound reasonable, but it deliberately leaves out an important part of the scientific evidence: plausibility.” The science-based medicine worldview, he wrote, “recognizes that clinical evidence is tricky, complicated, and often ambiguous. There is good evidence to support this position. John Ioannidis has published a series of papers looking at patterns in the clinical research. He found that most published studies actually come to what is ultimately the wrong conclusion, with a strong false-positive bias (Ioannidis 2005). This effect is worsened in proportion to the implausibility of the clinical question.”

This sort of thinking is catnip to me, and I believe we need more of. After all, I wrote a book, The Quick Fix: Why Fad Psychology Can’t Cure Our Social Ills, which relates many examples of faddish, half-baked-at-best psychological insights that appeared to be supported by a fair amount of published evidence at one point, only for the truth to turn out to be much more complicated (and usually much less exciting). Swap out a word or two here and there and everything Novella believes about the potential pitfalls of clinical evidence in medicine applies to the field of research psychology, too. It really isn’t enough to say “I believe in X because some studies say it is true” — at least not without knowing a lot more about the studies in question and the plausibility of the theories underpinning them.

Another subject I’ve written a fair bit about is the controversy over how to best help gender dysphoric children and adolescents — that is, young people who feel a great deal of distress about their biological sex, which they will often (though not always) describe as a sense of profound identity mismatch and/or being “trapped in the wrong body.” We have far less data about physical transition for youth, when it comes to both puberty blockers and hormones, than we do for adults. And there are myriad unknowns and tradeoffs that don’t apply, or at least not as much, to the adult setting. For one thing, 15-year-olds are, for obvious reasons, less equipped to think carefully about the future, and about how they might feel down the road, than 25-year-olds. For another, kids who go on blockers early, followed by cross-sex hormones, likely won’t be able to have kids, and even top clinicians aren’t sure if they will ever enjoy full sexual function. Does any of this mean physical transition is automatically a bad idea for young people? Of course not. Medicine often entails tradeoffs, and if the choice is “suffer from severe gender dysphoria for years and years” or “give up one’s fertility and potentially one’s sexual function,” there may well be many instances in which the latter is a superior choice to the former. But the point is this is a major medical decision that is often not treated like one.

In addition to writing about this subject for New York Magazine’s website when I worked there and for this very newsletter, in 2018, I wrote a long cover story for The Atlantic explaining many aspects of the controversy, and last month I wrote an article for The Spectator World about how mainstream outlets have failed, rather spectacularly, to communicate to readers that we have almost no quality evidence to rely on when making major medical decisions for this very vulnerable population. (I’m going to be excerpting my Spectator article throughout this one, mostly to avoid repeating points I’ve made previously, and if you are coming to this subject completely fresh, you will get more from this article if you read that one, and/or The Atlantic one, first.)

While my Spectator article was mostly given over to describing the present evidentiary landscape for youth gender medicine and providing examples of lackluster coverage of this subject, it also included a bit of informed speculation: Bad coverage is rampant, I argued, because this has become such a politicized issue — especially in light of ill-conceived conservative attempts to ban youth gender medicine outright at the state level in the United States.

In the present climate, to say that the evidence for blockers and hormones for young people is strong is to be a good ally who cares about trans kids and wants them to thrive; to point out the many gaps in the evidence is to be an ignoramus or bigot who, at best, doesn’t care if vast numbers of trans kids are driven into the closet and/or kill themselves — a ubiquitous claim in this space is that any delay in getting young people puberty blockers or hormones will inevitably lead to suicide attempts — and who at worst desires that outcome.

This sort of politicization of a very important scientific debate is pernicious for obvious reasons, and at first glance, a site like Science-Based Medicine would appear to be well-situated to serve as a useful balm to cool things down: Novella and Gorski enjoy leadership roles in a community of skeptics who aren’t afraid to step up and respond forcefully to confident overclaiming, whatever the politics of the overclaimer, on some of the most controversial subjects imaginable. And on this issue, confident overclaiming is rampant, so it’s a target-rich environment.

Unfortunately, that hasn’t happened. Instead, Science-Based Medicine has fallen into the exact same trap as numerous mainstream news outlets, violating some of its founding principles in the process. If you read the site’s recent coverage of this issue, you will come away thinking there is a big, broad, impressive body of evidence for youth gender medicine, that there isn’t any actual controversy here at all. Rather than evaluate the available evidence carefully, SBM defaults to just about every activist trope that has come to dictate the terms of this debate in progressive spaces. This is a disturbing example of what complete ideological capture of an otherwise credible information source looks like. Science-Based Medicine has “bought into the hype and failed to ask the hard questions.”

***

The trouble began when SBM recently published a favorable review of Abigail Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters by Dr. Harriet Hall, a longtime contributor to SBM who has written more than 700 articles for the site and who is listed as ‘Editor’ below Novella and Gorski themselves, rounding out the present masthead. To oversimplify, Shrier’s book argues that social contagion is causing many adolescent natal females to identify as trans and seek out medical treatments that will do far more harm than good, since they aren’t actually trans in any sort of deep-seated, durable sense, but are fundamentally confused and misled.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that this book is controversial, or that Hall’s positive review was met with some pushback. Novella and Gorski subsequently decided to retract the review entirely, replacing it with a statement that it had failed to meet SBM’s normal editorial standards and denying that the move was related to political pressure from the SBM community or anyone else. Hall’s review has been reposted by Skeptic Magazine, so you can read it there if you’d like to.

SBM has, in the wake of this retraction, published three articles about Shrier, Hall’s review of her book, and the broader controversy over youth gender medicine: “The Science of Transgender Treatment” by Novella and Gorski themselves, “Abigail Shrier’s Irreversible Damage: A Wealth of Irreversible Misinformation” by Rose Lovell, who as of February was finishing up a medical residency, and “Irreversible Damage to the Trans Community: A Critical Review of Abigail Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage (Part One)” by AJ Eckert, who serves as “the Medical Director of Anchor Health’s Gender and Life-Affirming Medicine (GLAM) Program” in Connecticut. Part Two is presumably on the way and I’ll read it when it’s published. (For what it’s worth, neither Lovell nor Eckert had written for SBM previously — they appear to have been brought on specifically for the task of responding to Irreversible Damage.)

All three articles contain major errors and misunderstandings and distortions, ranging from straightforward falsehoods to baffling omissions to the re-regurgitation of inaccurate rumors first circulated years ago. Activist claims that stretch or violate the truth are repeatedly presented in a credulous manner, while the myriad weaknesses in the research base on youth gender medicine are simply ignored. The basic problem here is what Scott Alexander calls “isolated demands for rigor.” This is a standard aspect of human nature, a close sibling of confirmation bias. When it comes to claims we don’t want to believe we will insist the evidence isn’t actually as strong as it appears, demand more and more clarification, shift the goalposts of the debate, and nitpick if necessary; for claims we do want to believe, we’ll wave weak evidence right through the gate without interrogating it too harshly, even if it suffers from exactly the same problems.

Isolated demands for rigor are a particularly big problem in areas where we don’t have a robust evidence base to rely on in the first place. Youth gender medicine is one such area, and throughout SBM’s coverage of this issue, the isolated demands for rigor target only research and individuals who appear to complicate the site’s favored narrative: There is nothing to be concerned about here, because youth gender medicine is in overall solid shape. At one point, faced with a published finding that could complicate their narrative, Novella and Gorski write it off as irredeemably bad research (though without explaining why). Then, later in the same paragraph, they accept as true a conclusion produced by the same youth gender clinic, most likely because that finding slots easily into their priors. It’s sort of a Schrödinger’s Evidence type of deal: Source X’s credibility exists in a fuzzy superposition of “totally credible” and “entirely untrustworthy” until we find out whether its claim fits comfortably within our politics, at which point its status collapses conveniently into one state or the other.

What makes SBM’s coverage of this issue so frustrating is that it was a big missed opportunity. Youth trans issues invite a huge amount of screaming and denunciation on all sides, and as a result, sometimes people think the circus itself — all those personalities yelling at each other online — is the actual issue here. But the actual actual issue here is the growing number of American families who face really difficult choices about puberty blockers and hormones that they are forced to make under a condition of terribly insufficient evidence. They desperately need institutions like Science-Based Medicine to step up and provide rigorous, science-backed advice untainted by the toxic climate that besets this issue, because hardly anyone, anywhere is doing so.

When I say there is “terribly insufficient evidence” for youth gender medicine interventions, that applies to the ‘traditional’ model of youth gender dysphoria, in which it manifests at a young age and persists at least until the onset of puberty. The evidence we have comes from this context, from kids who were assessed and watched over carefully for a fairly long period before any medical interventions took place. But things are even worse, now, given certain changes in clinic-referral patterns.

As I wrote recently in my Spectator article:

This is all going on at a time when youth-gender clinicians all over the world are noticing a marked increase in referrals, mostly of biological females. At some clinics teenagers are presenting at older ages than previously — and with no evidence of childhood GD. No one knows exactly how to explain this, but there’s evidence that some adolescents are, as a result of peer and cultural influence, diagnosing themselves as having gender dysphoria and seeking out treatment. This claim is viewed as offensive by some — and to be clear no one knows how frequently it occurs. I have encountered such cases in my own reporting. They were not hard to find.

The change in youth GD referral patterns was sufficiently concerning to Annelou de Vries[, a leading clinicians at the Dutch youth-gender clinic that came up with the puberty-blocking protocol, ] that she wrote a 2020 commentary in Pediatrics suggesting the emergence of a ‘new developmental pathway… involving youth with post-puberty adolescent-onset transgender histories’. ‘This raises the question whether the positive outcomes of early medical interventions also apply to adolescents who more recently present in overwhelming large numbers for transgender care, including those that come at an older age, possibly without a childhood history of [gender dysphoria],’ she wrote.

I should re-emphasize that I’ve said repeatedly I think banning youth gender medicine is a terribly bad idea. The evidence for those “positive outcomes of early medical interventions” come from research that, as we’ll see, leaves a lot to be desired. But it does suggest that for kids with intense, persistent dysphoria who have been well-evaluated, who have any other mental-health problems under control, and who have have good family support, puberty blockers and hormones are likely to lead to the amelioration of what would have been a great deal of suffering. (I include these conditions because we simply can’t say much about the effectiveness of these treatments under different circumstances.) I do not trust legislators to override doctors’ and psychologists’ decisions in a context like this. But again, the evidence here is thin and low-quality, so at the very least it is imperative that any truly ‘science-based’ outlet communicate this uncertainty to readers. Science-Based Medicine has failed to do so.

All that out of the way, below is my critique of the initial article by Novella and Gorski. In a future post or posts, I’ll cover the issues with the other articles in the series.

Problems in “The Science of Transgender Treatment” by Steven Novella and David Gorski

1. Novella and Gorski misinform readers about the difference between the DSM-IV and the DSM-5 entries for “gender identity disorder” and “gender dysphoria,” respectively.

In criticizing a comparison Abigail Shrier draws between adult responses to youth anorexia versus youth gender dysphoria, the authors write the following:

The analogy here is not apt. Eating disorders are clearly disorders, with now well-established diagnostic criteria and medical risks. The assumption behind the analogy is that feeling as if you are a different gender than the one assigned at birth is also a harmful disorder that should be “cured”. This assumption is not valid and is itself likely harmful. In fact Ms. Shrier relies on an outdated definition from the DSM-IV to make this case. The DSM-V now recognizes that having a gender identity that differs from the gender assigned at birth is not a disorder. Having dysphoria resulting from that fact combined with social factors is.

One of the main warning signs I look for when determining whether a given outlet is trustworthy on the subject of youth GD is whether it disseminates activist talking points without fact-checking them. This is one such talking point: the idea that in the DSM-IV, simply “being trans” and/or acting in a gender nonconforming way was considered a mental disorder, but then in the DSM-5, this injustice was rectified. It’s a tidy storyline that neatly parallels the delisting of homosexuality from the DSM in 1973. (If you’re curious why the American Psychiatric Association switched from Roman to Arabic numerals, that’s explained here.)

Major outlets helped seed this false belief, and I’ve been trying to debunk it since at least 2019, without much success. It just keeps getting repeated endlessly, including in very ostensibly rigorous outlets like the podcast Science Vs (the producers of which declined to correct this error after I pointed it out, though they did correct another one) and by some clinicians and writers with big platforms:

In that case, Turban, a frequent commentator on these issues, did eventually correct the false claim he published in Psychology Today:

It still runs rampant elsewhere, though.

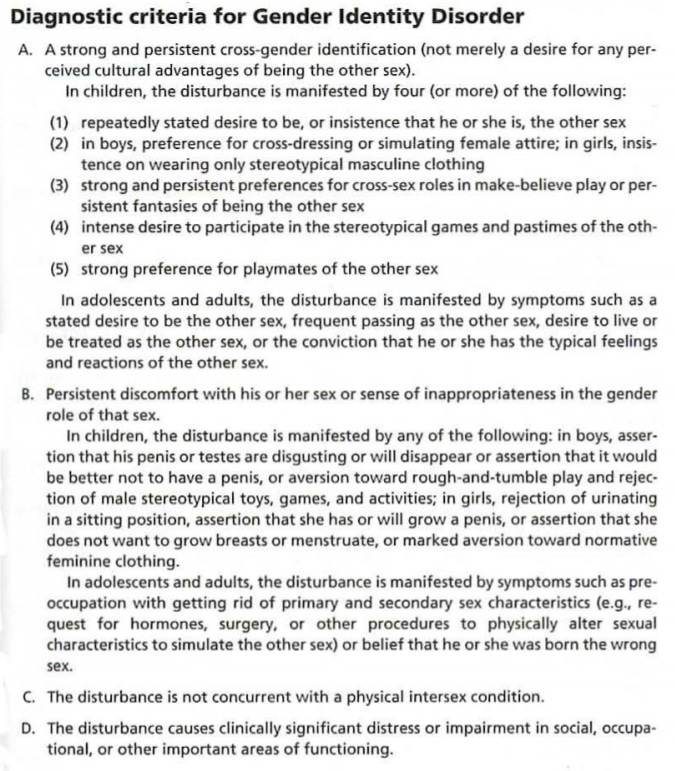

Here are the DSM-IV criteria that supposedly pathologize mere identification with a gender that doesn’t line up with one’s biological sex and/or gender nonconforming behavior:

It seems pretty obvious that if a young natal male said “I’m actually a girl,” but this identity wasn’t associated with other features that brought him anguish, that wouldn’t be enough for him to qualify under these criteria. This child would also need to experience actual dysphoria — that is clearly the phenomenon these criteria are attempting to capture — in various ways. The DSM-IV criteria do not have a diagnosis for someone who simply walks around being trans but who doesn’t exhibit the features and signs of distress listed in criteria A, B, and D.

Critics have harped on the fact that because criterion A(1) is optional in this listing, a child without a stated desire to be, or belief that they are, the ‘other’ sex could be diagnosed with GID. But when you look at all the other criteria they’d have to satisfy — A(2) - (5), plus B, C, and D — I think it’s a pretty big stretch to claim that such a child doesn’t have a condition we’d associate with a potential need to socially transition and go on puberty blockers or hormones in the long run.

The DSM-5 criteria, which you can read here and here (that’s kids and adolescents/adults, in that order), include various refinements, most notably, for our purposes, switching things around so that what was A(1) in the DSM-IV is a mandatory criterion in the DSM-5. But overall the two listings are pretty similar. It might be true that here and there, the DSM-IV led to the false diagnosis of a (likely) small number of kids who were merely gender nonconforming as having gender identity disorder, but it’s just hard to see how this could have happened all that frequently given the actual criteria, and given the existence, in the DSM-IV itself, of subsequent language specifically cautioning clinicians against making this blunder:

Gender Identity Disorder can be distinguished from simple nonconformity to stereotypical sex role behavior by the extent and pervasiveness of the cross-gender wishes, interests, and activities. This disorder is not meant to describe a child's nonconformity to stereotypic sex-role behavior as, for example, in “tomboyishness” in girls or “sissyish” behavior in boys. Rather, it represents a profound disturbance of the individual's sense of identity with regard to maleness or femaleness. Behavior in children that merely does not fit the cultural stereotype of masculinity or femininity should not be given the diagnosis unless the full syndrome is present, including marked distress or impairment. [emphasis in the original]

The switch Novella and Gorski and so many others have claimed occurred — that in IV simply “being trans” was a disorder while in 5 it isn’t — is nowhere to be found. Rather, what I think happened is that because the name of the disorder was changed from “gender identity disorder” to “gender dysphoria,” a bunch of people began making this claim out of pure confusion, and the rumor went viral because it made it easier to discount some of the desistance literature (more on which soon). But in both cases, the thing being listed is a disorder, and simply “having a gender identity that differs from the sex assigned at birth” or “being trans” is insufficient to receive a diagnosis.

This is a pretty basic thing to get wrong, and it suggests Novella and Gorski aren’t familiar with this subject, but are familiar with — and have accepted as true — some of the activist narratives surrounding it. It also will plainly misinform Science-Based Medicine readers, which is the opposite of the site’s goal.

2) Novella and Gorski argue that there is widespread adherence to the standards of care for youth gender medicine without providing any evidence that this is the case, other than referencing ‘countless’ interviews they neither quote from nor link to. They also misrepresent the World Professional Association of Transgender Health’s Standards of Care for the administration of hormones to adolescents.

Standards of care (SOCs) published by organizations like the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society explain what providers are supposed to do before and during the administration of puberty blockers and cross sex hormones to young people. The guidelines aren’t perfect, and WPATH is set to release a highly anticipated new set of standards by the end of the year, but these documents do tend to note, in at least a cursory way, the importance of careful assessment, mental-health support, and so on.

In the United States, these guidelines are nonbinding, and there is widespread disagreement over whether they are being consistently followed — in fact, a huge amount of this debate hinges on that very question. “When I look at what the [WPATH] SOC describes, and then I look at my own experience and my friends’ experiences of pursuing hormones and surgery, there’s hardly any overlap between the directives of the SOC and the reality of care patients get,” Carey Callahan, a detransitioner who herself worked in a gender clinic at one time, told me in 2018. “We didn’t discuss all the implications of medical intervention—psychological, social, physical, sexual, occupational, financial, and legal—which the SOC directs the mental-health professional to discuss. What the SOC describes and the care people get before getting cleared for hormones and surgery are miles apart.”

Callahan was a legal adult when she transitioned, but this issue applies even more urgently to youth care, and there are numerous anecdotal examples of young detransitioners who say they received blockers or hormones or both after hasty, threadbare assessment processes. Just poke around on the detransition subreddit and you’ll find plenty of such stories. (I don’t like that I have to point you to an anecdotal source either! But we have basically no research on this question.)

It isn’t just detransitioners — some highly regarded clinicians share these concerns. Here’s what the psychologists Laura Edwards-Leeper, who helped bring the puberty-blocking protocol to Boston in 2007 and who presently practices in Portland, and Erica Anderson, who is a trans woman herself and the president of the United States Professional Association for Transgender Health, told me last year:

“Yes, some kids are not getting sufficient assessments,” explained Anderson in an email (emphasis hers). “The quality of care for trans [people] varies a great deal.” Echoing concerns she expressed to me when we first met, Anderson told me that “Without question providers who are ill prepared to care for trans patients have attempted to do so. Some in my opinion did so because they felt obligated to do the best they could even without adequate training and experience. Others appear to have been opportunistic. Being transgender myself and a psychologist for so many years I see the gains that have been made thanks to WPATH and others. But suddenly trans is trendy and trans people seem like unicorns: fascinating objects of study. When I sense this happening I cringe and it feels very weird.” She doesn’t believe cases of poor youth evaluation are super-rare outliers. “I regularly encounter providers ignorant of the standards of care of WPATH,” she explained. “And assertive/anxious patients who have no tolerance for careful evaluation. It’s a toxic brew.” (In her email, she also noted that it’s perfectly natural and rational that trans people might be skeptical of what they perceive as overly aggressive gatekeeping, given what members of that community have endured in the past.)

Edwards-Leeper pointed out that parents who genuinely want what is best for their kids face a difficult situation if they’re unlucky enough to be in one of the many areas of the country without competent, well-trained youth gender clinicians. “What is problematic is that so many parents these days have reasonable concerns and cannot find a mental health provider who has been adequately trained to assess the gender concerns and ‘readiness’ for irreversible interventions from a psychological perspective,” she explained in an email (emphasis hers throughout). “This results in well-meaning parents being left to make decisions in their child’s best interest without true professional guidance. It puts parents in a horrible position and my heart goes out to them.” She explained that yes, some parents are too skeptical of medical transition, and might wrongly stall their child’s access to blockers or hormones despite a competently conducted diagnosis. “But what about the parents who disagree with the therapist who decided in a 1-hour appointment that their child who came out last week as trans after stumbling upon a YouTube video is ready for testosterone?” Like Anderson, Edwards-Leeper does not believe these cases are extreme outliers. Rather, she has heard from hundreds of parents in these sorts of situations since she was featured in my Atlantic article. “These are the parents who I have banging down my door still, since the Atlantic article,” she explained. “I can’t tell you how many times I'm almost in tears about the state of this field when I get off the phone with them.”

In addition to speaking with me, Edwards-Leeper and Anderson recently echoed these concerns on 60 Minutes (requires a subscription). Both of them are ardently in favor of helping trans kids, and view blockers and hormones as potentially life-saving when properly administered. But they are as well-positioned as anyone to gauge the present state of the field, and they think there is a problem here.

Part of that problem is that some clinicians themselves are opposed to providing careful assessment and mental-health support to kids being put on blockers or hormones, because they view this as an onerous level of gatekeeping and are confident in their ability to quickly determine which kids and teens will benefit from these treatments.

To a vocal group of American clinicians and activists ardently seeking to expand access to youth medical transition, [the Dutch protocol] is too cautious an approach — and there has been a backlash among some of them, not only against outright conversion therapy but also against Dutch-style ‘gatekeeping’. In 2018, [Edwards-Leeper] told me about ‘things almost being thrown at me at conferences’ because she favors in-depth assessment prior to medical transition.

While there are certainly some big, multi-disciplinary US youth-gender clinics that take a similar approach to the Dutch, access to them is limited — and not all clinics stress careful assessment prior to the administration of blockers or hormones. One, housed at the Center for Transyouth Health and Development at the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, for example, is the largest youth-gender clinic in the country. In a 2018 study of young people on hormones aged 12 to 24, the center reported that it had only been able to collect follow-up physiological data on about 60 percent of them — a high ‘lost to follow-up’ rate perhaps reflecting a laissez-faire approach to assessment. The often-quoted medical director there, Johanna Olson-Kennedy, is skeptical of in-depth assessments. ‘I don’t send someone to a therapist when I’m going to start them on insulin,’ she told me in 2018.

At the very least, there is clearly some debate here. I would never claim Anderson and Edwards-Leeper reflect some sort of supermajority opinion among clinicians, and have never presented things as such. But there are major philosophical differences from clinician to clinician when it comes to what constitutes proper safeguarding for kids going on these treatments, and how concerned we should be about clinicians who cut corners, whether due to ignorance or ideology.

So how do Novella and Gorski handle all of this? They ignore it, pretending the controversy is completely ginned-up by (what they view as) bad-faith actors like Shrier:

[L]ooking at published standards and countless interviews with practitioners, the notion that those involved in gender care are caving to political correctness rather than best practice is an unfair caricature that is clearly motivated more by ideology than science and medicine … Of course, these are standards, and not every practitioner adheres perfectly to the standard of care in any aspect of medicine. But we don’t take outliers and use that to criticize the standard or pretend it is typical or common. Interviews with those involved in transgender care indicate that adherence to rigorous standards as outlined above are the norm.

Of course their phrasing makes this whole exercise silly — I’d never claim that anything as simple as “political correctness” is driving potentially subpar care of transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth. But Novella and Gorski don’t quote anyone or explain who they talked to or provide any other basis for their view. If you’re trusting these two to give you accurate information, this sort of thing should worry you a great deal:

Steven Novella and David Gorski, two physicians with no firsthand experience with youth gender medicine: “Interviews with those involved in transgender care indicate that adherence to rigorous standards as outlined above are the norm.”

Erica Anderson, president of USPATH: “I regularly encounter providers ignorant of the standards of care of WPATH.”

Because Novella and Gorski pretend figures like Edwards-Leeper and Anderson don’t exist, they don’t have to attempt to reconcile their own claims with what these leading experts have now been saying for years. During these “countless interviews,” did Novella and Gorski come across any concerns on this front? Did they consult with any detransitioners? How did they encounter such a uniformly rosy assessment of the current state of youth gender medicine when it is a site of such obvious, roaring controversy that big-name figures have begun going on the record with their concerns?

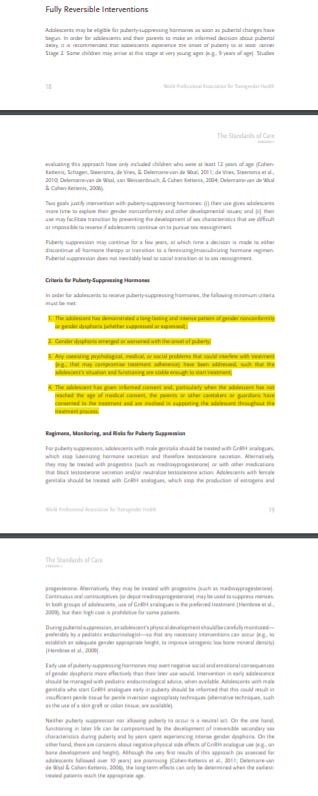

In this section, Novella and Gorski also reveal, again, their unfamiliarity with the source material they are confidently opining about. Immediately after excerpting the WPATH SOC’s criteria for puberty blockers, they write, “These standards are for fully reversible interventions. Partially reversible interventions, including cross hormone therapy, have stricter criteria for assessment and informed consent.”

Setting aside the question of whether WPATH should call puberty blockers “fully reversible” — that’s a whole other issue — this claim is false. The “Partially Reversible Interventions” section of the WPATH SOC comes right after the “Fully Reversible Interventions” section, and it is a grand total of two paragraphs, with far less detail than what precedes it:

Partially Reversible Interventions

Adolescents may be eligible to begin feminizing/masculinizing hormone therapy, preferably with parental consent. In many countries, 16-year-olds are legal adults for medical decision-making and do not require parental consent. Ideally, treatment decisions should be made among the adolescent, the family, and the treatment team.

Regimens for hormone therapy in gender dysphoric adolescents differ substantially from those used in adults (Hembree et al., 2009). The hormone regimens for youth are adapted to account for the somatic, emotional, and mental development that occurs throughout adolescence (Hembree et al., 2009).

That’s it. That’s everything WPATH’s SOC 7 has to say about giving hormones to adolescents, other than some general guidance on mental-health support for TGNC youth found elsewhere that applies to other interventions as well. There is a longer section on adult hormones later in the document, but that section is explicitly not designed to provide guidance for youth clinicians — it lists one of the criterion for prescribing hormones, on page 34, as “Age of majority in a given country (if younger, follow the SOC outlined in section VI),” “section VI” being the youth section Novella and Gorski are referencing. The section on blockers is much longer, though still fairly short — all it takes to know this is to read the document.

Here’s a visual comparison of the prior section versus the latter section:

Versus:

All these errors point in the same direction. “Huh, the WPATH SOC section on youth hormones is just two paragraphs and doesn’t even list explicit criteria” is the sort of realization that might cause a reader to ask certain questions about the state of youth gender medicine, especially given the other evidentiary concerns we’ll get to. Novella and Gorski can’t have that — they appear to be committed to presenting this area of research and clinical practice in as positive a light as possible — so they falsely tell readers that this section consists of “stricter criteria for assessment and informed consent” than the section on puberty blockers, even though a 20-second perusal of pages 18-20 of the Standards of Care immediately proves otherwise.

3) Novella and Gorski badly misunderstand the nature of the desistance debate and communicate a great deal of misinformation and undue skepticism about the desistance literature to their readers.

In attempting to rebut Hall’s claim that most young children with gender dysphoria will grow out of it without any intervention — that is, they will ‘desist’ — Novella and Gorski write:

[T]he fact that young children may alter their identity as they mature is based on highly flawed research, studies with methods so fatally flawed that the results cannot be trusted, let alone cited as facts. But even if this statistic were reliable, it is less relevant to the discussion. As stated above, there are no medical interventions for this group of children. Medical gender-affirming interventions are reserved for adolescents and older. The data on adolescents is very different. While more data is certainly desired, the statistics we have indicate that nearly all adolescents who identify as trans maintain that identity into adulthood.

Here Novella and Gorski are, again, amplifying a common activist talking point: not that the desistance research has some questions or holes (which it certainly does), or that the commonly cited figure that 80% of kids with GD desist might be too high (it probably is and I’ve stopped using it — Hall says 70%, for what it’s worth), but that this body of research is so bad and so broken that we should treat it as worthless — “the results cannot be trusted,” full-stop.

The desistance research, or at least the subset of it we should favor over older, smaller-sample-size studies, comes from the aforementioned Dutch youth gender clinic and another, Canadian one. (My first truly controversial article on youth GD came from my investigation into the largely false and overhyped misconduct claims that led the Canadian clinic to be closed — a later legal settlement confirmed that the overseeing hospital responsible for the closing had acted negligently.) Both these clinics discouraged early social transition, and both found desistance to be quite common.

The idea that this research is too flawed to offer any meaningful evidence stems from the claim that the Dutch and Canadian clinicians wrongly identified kids as gender dysphoric who were really just gender nonconforming (say, a boy who is fundamentally fine with being a boy, but likes to dress up as a princess, grow his hair long, and so on), because of those lackluster DSM-IV criteria and other problems with how these clinicians went about their business. The thinking goes that if you wrongly identify a gender nonconforming boy as having gender dysphoria at age 8, then find out at age 18 he identifies as male, this isn’t an example of true desistance because he never had actual gender dysphoria in the first place.

You see this claim a lot. In an unfortunately influential article she wrote for the Huffington Post headlined “The End of the Desistance Myth,” the trans activist Brynn Tannehill wrote that some of the Dutch research “did not actually differentiate between children with consistent, persistent and insistent gender dysphoria, kids who socially transitioned, and kids who just acted more masculine or feminine than their birth sex and culture allowed for. In other words, it treated gender non-conformance the same as gender dysphoria.” In a ThinkProgress article that rather hysterically referred to the desistance data as “The pernicious junk science stalking trans kids,” the journalist Zack Ford made similar claims (authors don’t always choose their headlines, but still).

This is now treated as a capital-t Truth by many activists and journalists, but it really shouldn’t be. It may be the case that as a result of the DSM-IV criteria being slightly looser than the DSM-5 ones, here and there these two clinics misdiagnosed merely gender nonconforming kids as having GD. This certainly could have occurred at the margins. But the idea that the Dutch and Canadian clinicians fundamentally did not understand the difference between mere gender nonconformity and gender dysphoria — that they were so bad at it we need to hurl all their research in the trash and pretend there’s no evidence for desistance, that this body of work “cannot be trusted” — really makes no sense on multiple levels.

I’ve already explained why at great length and am not going to rewrite that post here, but the short version is that you can simply read the research the Dutch and Candian clinicians have published and see that they utilized tools that were designed to detect this exact distinction — both the DSM-IV criteria (with its accompanying caution about the potential for misdiagnosis) and other psychological scales. Diagnosis of childhood gender dysphoria is generally made on the basis of both stereotypical “cross-gender” behavior, which is associated with gender dysphoria but not, on its own, sufficient evidence of it to warrant a diagnosis, but also criteria geared at gauging the presence of a more deep-seated sense of identity mismatch.

This instrument, for example, which I also embedded in the above-linked-to post, was used by these clinicians and clearly asks kids questions about not just gender nonconforming behavior, but also some of the other, more visceral features of gender dysphoria.

If a natal male child believes they are really a girl and/or are going to grow up to be a ‘mommy’ and/or that when they were in their “mom’s tummy,” they were in some sense supposed to be a girl, then of course what’s going on is different from mere gender nonconformity. No one who has read this research closely could come away claiming the clinicians who authored it were so clumsy they didn’t understand this important distinction.

More broadly, if you know about these clinics’ general philosophies, this accusation makes even less sense. Both of them took an approach that was basically We think most kids will desist, but that blockers and hormones might be good options for those who don’t. Whatever you think of this, the clinicians following this protocol were very intent on figuring out who would desist and who wouldn’t!

Focusing on the Dutch clinic, imagine that this claim were true — that the clinicians who pioneered the puberty-blocking protocol for trans youth could not differentiate “girly boys” from genuine trans girls. This would suggest a major scandal: It would mean that the Dutch relied on worthless diagnostic criteria to put many patients on powerful medications — medications most of these patients are still on today, often as young adults. Weirdly, the critics claiming confidently that the Dutch clinic had trouble distinguishing gender nonconforming cisgender children from transgender ones don’t seem all that concerned about this; rather, their concern only extends as far as ‘debunking’ the desistance literature.

I tried to raise this point with Novella and Gorski but they ignored me. Last month, after I saw they had retracted the Hall review and I decided I wanted to write about this, I sent them some questions. As part of his justification for the retraction, Novella wrote back, “Shrier also promotes the idea of ‘rapid onset gender dysphoria’ - that children sometime[s] suddenly realize they are trans. To say this notion is shaky is an understatement. This, in fact, is a major pillar of her narrative, and is most likely false. To bolster this idea she quotes figures, such as the notion that 70% of children who identify as trans later change their mind. Multiple topic experts have pointed out that this was due to a change in diagnosis from DSMIV to DSMV, and that Shrier confused gender identity disorder with gender dysphoria.”

In my response to Novella and Gorski, I asked how these “topic experts” were chosen and whether, in arguing that ROGD is “most likely false,” Novella was saying the phenomenon never occurs, or just that it is such a rare and outlying event that we should ignore it. I also pasted in the DSM-IV criteria and wrote: “[D]o you think it’s the case that these criteria picked out many kids who weren’t gender dysphoric, but merely gender nonconforming? If this is a valid criticism of the DSM-IV criteria, doesn’t it raise the possibility that the Dutch clinicians responsible for a lot of the desistance research negligently put many kids on irreversible medications since, in this argument, they were relying on criteria that merely picked out gender nonconforming, rather than truly gender dysphoric, youth?” I didn’t receive a response to any of those followup questions, which is fine — Novella and Gorski have no obligation to respond to my queries. But about a week and a half later they published their article, getting this stuff very wrong, in my opinion.

They also appear to be confused about the question of at what point in a child’s development clinicians feel fairly confident that their gender dysphoria is not going to desist. They write that “the statistics we have indicate that nearly all adolescents who identify as trans maintain that identity into adulthood.” This finding comes mostly from the Dutch clinic: “In contrast to what happens in children, gender dysphoria rarely changes or desists in adolescents who had been gender dysphoric since childhood and remained so after puberty,” wrote some of those clinicians in 2012, citing both their research and that of their Canadian counterparts.

That last bit — “who had been gender dysphoric since childhood and remained so after puberty” — is crucial. The evidence we have on this subject does not come from adolescents who suddenly came out as trans in their teens, but rather from those had been gender dysphoric awhile. That is the population for whom clinicians are most comfortable saying, “This young person is most likely to identify as trans in the long run.”

So when she describes her concerns, Hall is talking about kids who come out in adolescence and who don’t appear to have any childhood gender dysphoria — they are the focus of the present ROGD conversation. For this group, I believe the number of studies tracking how many of them continue to feel dysphoric and/or identify as trans in even the medium term is… zero.

Again, it isn’t just random internet reactionaries raising this concern about kids with apparently later-onset GD. To repeat some quotes from earlier, Annelou de Vries of the Dutch clinic recently wrote in Pediatrics of a “new developmental pathway… involving youth with post-puberty adolescent-onset transgender histories,” and said that “This raises the question whether the positive outcomes of early medical interventions also apply to adolescents who more recently present in overwhelming large numbers for transgender care, including those that come at an older age, possibly without a childhood history of [gender dysphoria].”

So when Novella and Gorski write that “the statistics we have indicate that nearly all adolescents who identify as trans maintain that identity into adulthood,” and that therefore Hall’s concerns are misguided, this is, in context, a pretty basic misrepresentation, because it simply doesn’t apply to the population Hall is discussing. Hall is saying something like “We should be concerned about kids who suddenly feel trans as adolescents since we don’t know much about their longer-term trajectories,” and Novella and Gorski are responding by saying something like, “What do you mean? Trans adolescents who have felt that way since childhood tend to stay trans.” Their answer is a non sequitur. A confidently-delivered one.

Now, the WPATH SOC does contain language explaining that “many adolescents and adults presenting with gender dysphoria do not report a history of childhood gender-nonconforming behaviors. Therefore, it may come as a surprise to others (parents, other family members, friends, and community members) when a youth’s gender dysphoria first becomes evident in adolescence [citations removed].” So even as of 2012, when that document was published, this was by no means a completely unknown phenomenon. And as I’ve written previously, I think it’s a potentially disastrous mistake for parents to believe that just because their teen appeared to develop GD ‘suddenly,’ they aren’t “really trans.” Things can often be more complicated than that, and there are certainly instances of kids misunderstanding or suppressing strong feelings of gender dysphoria.

But the point is that all the (limited) data we have attempting to correlate age of GD onset with the likelihood of GD persistence comes from samples of what were initially gender dysphoric kids. Conflating “trans adolescents who have had gender dysphoria since childhood” with “trans adolescents who recently came out despite an apparent lack of childhood GD” is a mistake one can only make if one is completely unfamiliar with the basic contours of this debate — or trying to be obfuscatory. Novella and Gorski should correct this, because if I’m wrong and the actual number of studies on late-onset GD teens’ trajectories isn’t zero, it’s close to it (I do think it’s actually zero). They are spreading scientific misinformation via Science-Based Medicine — strictly speaking, the claim “the statistics we have indicate that nearly all adolescents who identify as trans maintain that identity into adulthood” is false unless it includes a modifier about earlier-onset GD.

To make a more general point about the lack of consistent standards in this entire SBM article, I can’t resist mapping out the sources in this paragraph:

Furthermore, the fact that young children may alter their identity as they mature is based on highly flawed research, studies with methods so fatally flawed that the results cannot be trusted, let alone cited as facts. [<-- this finding mostly comes from the Dutch clinic] But even if this statistic were reliable, it is less relevant to the discussion. As stated above, there are no medical interventions for this group of children. Medical gender-affirming interventions are reserved for adolescents and older. The data on adolescents is very different. While more data is certainly desired, the statistics we have indicate that nearly all adolescents who identify as trans maintain that identity into adulthood. [<-- this finding mostly comes from the Dutch clinic]

Again, Schrödinger’s Evidence: When the Dutch find that most kids desist, their “methods [are] so fatally flawed that the results cannot be trusted.” When the Dutch find that trans adolescents tend to stay trans, no such qualms. Isolated demands for rigor, indeed.

4) Novella and Gorski badly misunderstand Hall’s concern about regret.

After introducing this cohort of later-onset GD youth in her book review, Hall writes, “We are starting to see desisters (those who stop identifying as transgender) and detransitioners (those who had undergone medical procedures, regretted it, and tried to reverse course). No statistics are available on how often this happens.”

The concept of desistance well predates the current ROGD conversation, so it’s a bit confusing for Hall to write that “we are starting to see desisters.” But it’s clear, in context, that she’s saying we lack statistics on regret and desistance/detransition for later-onset GD youth who transition.

But Novella and Gorski respond as though she had claimed we have “no statistics” on the broader question of outcomes for trans adults. They write:

This is misleading. First, it is not true that we have no statistics. But further, if it were true, then how would we know that the incidence [of regret] is increasing? Her two claims, which appear to come from Ms. Shrier’s book, contradict each other. It turns out, both are wrong.

A 2021 meta-analysis of regret following gender affirming surgery, combining 27 studies and 7,928 transgender patients, found that the pooled prevalence was 1%.

A 2018 survey of surgeons about their own patient statistics found that out of 22,725 patients who underwent GAS only 62 later expressed regret, and out of these only 22 said it was because of a change in their gender identity. The rest cite reasons such as conflict with family or dissatisfaction with the surgical outcome.

Other reviews also find extremely low rates of regret, ranging from 0.3% to 3.8%. Further, if anything the rate of regret is decreasing over time as social support and surgical procedures improve.

But none of these studies come from the present American context, and I don’t think any of them have to do with late-onset GD youth. Rather, they appear to be almost entirely drawn from research conducted on adults who physically transitioned a fairly long time ago, and when it comes to trans medicine, even a decade is a lifetime — puberty blockers just hit the trans healthcare scene in the U.S. in 2007. For most of the span during which mainstream trans medicine has existed, access to physical interventions has been much more gatekept than it is now, which raises the risk of apples-to-oranges comparisons. With more gatekeeping, it could be that only the most dysphoric people — or the wealthiest, or best-connected to healthcare, or whatever — successfully obtained these procedures, which could certainly affect regret rates.

For example, one of the studies included in the 2021 meta-analysis examined the outcomes of 66 natally male German patients who had bottom surgery between 1995 and 2000, and was published in 2001. Surely Novella and Gorski are aware that 1) the present debate is mostly over puberty blockers and hormones for young Americans, not adults; and 2) while it is good news for all involved that 90% of the trans women who responded to a long-term followup questionnaire were happy with surgeries they received in Germany in the 1990s, this tells us almost nothing about what our own practices should be with regard to TGNC youth in 2021, in an entirely different medical and cultural and social setting.

That’s even setting aside methodological issues that would surely inspire some skepticism in Novella and Gorski if the studies in question were being presented as evidence against their favored hypotheses. As you’ll remember, the SBM philosophy is, wisely, to not take studies at face value, but to interrogate their methods. Some of the methods of the papers they are touting here leave a bit to be desired. The survey of surgeons, for example, is just an abstract from an annual convention of plastic surgeons rather than a peer-reviewed paper. For it, “Surgeons were asked to select a range representing the number of transgender patients they have surgically treated, and this amounted to a cumulative number of approximately 22,725 patients treated by the cohort.” So this is a very rough number, at best, drawn from the self-reports of a group whose members are motivated to think they are doing a good job. And as detransitioners will tell you, they often don’t go back to the clinicians they feel offered them subpar care. Any study of regret that doesn’t attempt to track down patients who are not currently in contact with their clinicians risks undershooting the mark (though contacting such lost-to-followup patients is, to be fair, a difficult task for researchers to pull off).

I’m not saying we should take nothing from these studies. Again, if regret rates for gender-affirming surgeries are low, that’s good, and I’m not aware of any research suggesting they are high, though I do wonder how many articles properly account for lost-to-followup patients (this is not an area I’ve looked into closely, though). But I am making a very 101-level observation in pointing out that the existence of these studies tells us very little about whether we should find Hall’s and Shrier’s concerns credible. Again, Novella and Gorski are answering a different question from the one that was asked.

5) Novella and Gorski write off Lisa Littman’s study of rapid onset gender dysphoria as “bad science” without explaining why or engaging with Littman’s own rather credible defense of her work, and they engage in some methodological cherrypicking in order to do so.

The one study we have on ROGD was published in PLOS One by Littman in 2018, and it came under immediate, sustained attack by activists and journalists hostile to the idea that some kids are determining they are trans on the basis of peer or cultural influence. The pressure led Brown University to retract its press release touting the study, and for PLOS One to take the unusual step of publishing a ‘correction’ of a study that, according to the journal itself, had no factual errors:

Most of the criticism stemmed from the fact that Littman surveyed communities of parents who were skeptical their kids were really trans, and she only included responses from parents rather than soliciting reponses from their kids as well. But Littman was not attempting to make any strong, specific claims about ROGD, but rather to simply publish an initial paper about the possible existence of the phenomenon and what she found when she asked some parents about it. For this sort of preliminary research, I believe what she did would not be considered particularly unusual or fraught in non-politically-charged contexts.

Here’s what Novella and Gorski say about Littman’s work:

To bolster the “social contagion” hypothesis, Dr. Hall cites the controversy over “Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGD)”. This idea was proposed in 2016, based on a single study that even Dr. Hall now acknowledges to have been bad science. The journal later published a “correction” that mainly added a proper discussion of the preliminary nature of the study. At this point is it not valid to cite ROGD to support the social contagion hypothesis, nor is it valid to suggest that there is now a burden of proof to rule it out, or that it should in any way inform medical practice. This is a thin hypothesis based on shoddy science; it should no more affect medical practice than similar-quality studies should impact the vaccination program.

If you click on the link, you’ll notice that it doesn’t point to Littman’s paper itself, but rather to a critique of it. As a general rule for online critical thinking, this is a good thing to keep an eye on: If someone doesn’t want you to read the actual thing being criticized, but skips right to criticisms of it, it might be a sign of chicanery (here you go).

In what sense was the Littman paper ‘bad’ or ‘shoddy’ science? Why should we discount it so forcefully, placing it in the same general basket as vaccine denialism, even as we accept arguably weaker papers making stronger claims (more of which are to come) which support Novella and Gorski’s nothing-to-see-here hypothesis? They don’t say. But as Littman wrote in a followup paper in the Archives of Sexual Behavior published in 2020, she made the same methodological choices central to research often cited approvingly by those who criticize her work. None of Littman’s critics, for example, seemed to mind that some of the research taken to support “gender affirming” approaches to TGNC youth come from parental reports from communities that strongly believe their kids are trans. Scientifically, it doesn’t make sense to say that certain research methods are off-limits for papers pointing one way but not another, especially in a situation like this where there is genuine uncertainty and debate over the long-term trajectories of gender dysphoric kids and teens.

Because, as is the case throughout this article, Novella and Gorski are so vague in their criticisms, it’s hard to know exactly what they’re saying about Littman’s work or how to respond to it. But assuming they accept as valid the most common criticism of this paper — that Littman reached out to parents rather than kids — it’s noteworthy that three paragraphs before denouncing her research as useless, Novella and Gorski approvingly cite that survey of surgeons. If the standard is you have to survey the individual themself and can’t extract any useful data from someone talking about that person, how could it be that this standard applies to the parent/child dyad but not the surgeon/patient one? Again, it seems like the standards Novella and Gorski rely on to judge research aren’t fixed, but rather swing, rather wildly, on the basis of what is being claimed.

Anyway: At the very least, there is a good-faith case to be made that the campaign against Littman’s research was, well, bad-faith. Science-Based Medicine didn’t have to (again) simply recite the previously-agreed-upon activist talking points. Of course Novella and Gorski were under no obligation to agree with Littman’s conclusions or tout the searing brilliance of her research, either. But had they been acting like serious science communicators instead of activists, they could have, for example, simply pointed out that some of the criticisms of Littman’s methodology also apply to other research that doesn’t appear to have attracted any ire. That’s what a more scientific, less ideologically captured version of this Science-Based Medicine article would have looked like.

6) Novella and Gorski falsely report the result of one study and ignore the fatal weaknesses in another.

As we’ve seen, to dispute Hall’s claim that, as they summarize it, “gender-affirming [medical] interventions are risky or harmful” for youth, Novella and Gorski mention a fair number of studies of adult transition outcomes that do not bear directly on this question, for reasons I laid out in the introduction to this article.

I believe the only point in their article where they cite medical outcome research specific to trans youth is when they write:

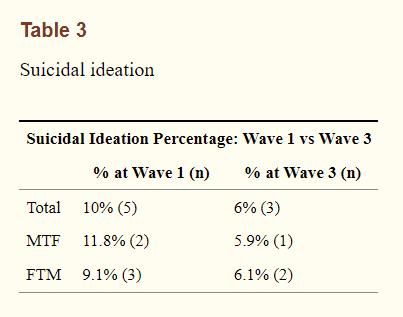

A 2020 study of hormonal therapy in trans teens found it decreased suicidal ideation and improved quality of life. A 2020 study of pubertal blockers and suicidal ideation found:

[this is from that study’s abstract:] This is the first study in which associations between access to pubertal suppression and suicidality are examined. There is a significant inverse association between treatment with pubertal suppression during adolescence and lifetime suicidal ideation among transgender adults who ever wanted this treatment. These results align with past literature, suggesting that pubertal suppression for transgender adolescents who want this treatment is associated with favorable mental health outcomes.

The first claim, that the 2020 study found hormone therapy “decreased suicidal ideation and improved quality of life,” is a serious misrepresentation of that study’s findings. And the suicide claim, in particular, should absolutely be corrected given that the authors of the study directly contradict it, and given the importance of the subject matter.

For that study, the authors looked at a cohort of adolescents and young adults who had gone on puberty blockers and/or hormones and used various instruments to track their depression, suicidality, and quality of life over three waves — at baseline, about six months later, and about 12 months later. Here’s the Results section of their abstract:

Between 2013 and 2018, 50 participants (mean age 16.2 + 2.2 yr) who were naïve to endocrine intervention completed 3 waves of questionnaires. Mean depression scores and suicidal ideation decreased over time while mean quality of life scores improved over time. When controlling for psychiatric medications and engagement in counseling, regression analysis suggested improvement with endocrine intervention. This reached significance in male-to-female participants.

“Suggested improvement” is already pretty hedgy language, and “reached significance in male-to-female participants” tells us the results didn’t reach significance in female-to-male participants. So already we have some hints of fairly wobbly findings. That is, if you read the abstract itself rather than the SBM summary of it.

Strikingly, Novella and Gorski take these claims, which are phrased by the researchers in either non-causal (“improved over time”) or tepidly causal (“suggested improvement”) manners, and transform them, via their phrasing of the summary, into a stronger, more robustly causal finding: “[H]ormonal therapy in trans teens… decreased suicidal ideation and improved quality of life.” Taking a relationship that may or not be causal and presenting it straightforwardly as causal is exactly the sort of misleading science communication Science-Based Medicine is supposed to criticize, not engage in. (This is such a common and basic issue that it’s no surprise that the word ‘causal’ and its variants pop up constantly on the website.)

So yes, “Mean depression scores and suicidal ideation decreased over time” in the study participants, but when you dig into the results there might not be much ‘there’ there. For one thing, not all of those decreases were statistically significant. For another, in the statistical models in which the authors controlled for patients’ engagement with counselling and psychiatric medicine, none of the supposedly positive results reached the p < .05 bar for statistical significance for female-to-male transitioners, and just one did (and three almost did), for male-to-female transitioners.

So the paper appears to offer marginal at best evidence that access to puberty blockers and/or hormones was associated with better outcomes for male-to-female transitioners, and effectively none that it helped the female-to-male ones. And this was an observational study rather than a fully controlled experiment, anyway, though to be fair there basically aren’t any of the latter when it comes to research on blockers and hormones. Because of the overhyped way in which Novella and Gorski summarize the findings, readers of SBM who don’t click through and read the paper will come away with a rather overinflated understanding of its results.

As for suicide, the authors of this paper are very open about the fact that they didn’t even have the data they needed to examine that issue rigorously: “Regression models for suicidal thoughts were not estimable due to the low frequency of endorsement and small cell sizes across gender.” Sure enough, just 10% of the total sample was suicidal at baseline — a grand total of two of the natal males and three of the natal females.

Technically speaking, there are decreases here, since the numbers of suicidal natal males and natal females dropped by one each from Wave 1 to Wave 3. But from a statistical perspective, as any capable AP Statistics student could tell you, this doesn’t necessarily mean anything. SBM really should correct the claim that this study showed a meaningful statistical link between endocrinal interventions and reduced suicidal ideation given that not even the authors claim that. Surely Novella and Gorski know the difference between a raw increase or decrease in some statistic and a statistically meaningful result. And surely, for that matter, they know the difference between a statistically significant correlation and a causal relationship. They are not making one but two big leaps here that, again, would not be accepted in a high-school stats course.

To be fair, when it comes to this study’s overall lack of statistically significant results on the depression and quality of life measures, this could, as the authors note, be a sample-size issue, and they point out that “effect sizes... values were notably large in many models.” I will leave it to the smarter stats-heads to litigate the quality of this study. But the point is, imagine if a researcher published an observational study which she claimed showed that access to puberty blockers and hormones was associated with worse mental-health and quality-of-life outcomes over time, but in which almost none of the results were statistically significant for one sex, and none of them were for the other. Is there any chance that Novella and Gorski would accept this as a worthwhile finding, nudging them away from their confidence in the efficacy of these interventions? Of course not. They would quickly highlight the mostly insignificant results as a compelling reason to disregard the study.

I suspect that this is all a game of cherrypicking for them: The desistance data is useless. Littman’s study is worthless. This study, though? Now that’s Science-Based Medicine™. Just don’t look past the abstract, and definitely don’t read any of the tables.

What about the “2020 study of pubertal blockers and suicidal ideation” that appeared to show access to the former reduced the latter? It’s an even weaker finding. But, again, you’d never know that from reading Novella and Gorski’s article.

In this politicized hothouse, questionable claims that support the ‘right’ political conclusions flourish. For example, last year Pediatrics published a study in which a team led by Jack Turban — a fellow in psychiatry who racks up many media hits promoting the view that concerns over youth transition are overstated — purported to demonstrate a link between access to blockers and reduced risk of suicidal ideation. His paper is rife with crippling methodological problems.

The researchers took data from the 2015 United States Transgender Survey (USTS), a big sample recruited online, and zoomed in on the subset of respondents who reported ever having wanted puberty blockers. Then the researchers attempted to correlate this group’s access to blockers to various outcomes. In the controlled models, the only outcome that was statistically significant was lifetime suicidality: among respondents who reported ever having wanted blockers, those who reported receiving them reported lower lifetime suicidality than those who reported not having received them. Hence, the claim that blockers reduce suicidal ideation.

Except that, as the Oxford sociologist Michael Biggs and a number of other critics pointed out, causality could just as easily go the other way: maybe those in the higher-suicidality group were more suicidal as youngsters, and the clinicians they went to for blockers followed guidelines which state that the medication should not be administered if a child has serious mental-health problems. The design of the study offers us no reason to view this as a less likely explanation. While the authors briefly mention the causality issue in the study itself, Turban subsequently gave interviews and wrote a New York Times column that ignored it. (In the column, he actually misrepresented his own study as having measured young-adulthood suicidal ideation rather than lifetime suicidal ideation, which would support his preferred causal explanation.)

There’s an arguably bigger problem with the study, anyway, also highlighted by Biggs: 73 percent of the respondents to the USTS who said they’d been on blockers reported receiving them at age 18 or later. Since blockers aren’t usually given past age 16, this clearly indicates that the respondents didn’t know what blockers are — and that they, as the authors of the survey themselves suggest, have likely confused them with cross-sex hormones. To address this, Turban and his colleagues simply tossed out the results from this 73 percent, but given the extent of the confusion, why should anyone think it didn’t apply to the younger respondents too?

In short, we have no idea how many of the respondents who said they received puberty blockers actually did so; it could reasonably be argued that this study offers us zero evidence about the mental health benefits of blockers. And yet the New York Times (repeatedly, including via Turban’s column), the Washington Post, Vox, Axios, CNN and many other outlets all summarized the paper in a manner very likely to confuse readers into thinking the study’s conclusions stemmed from a real-world clinical sample.

Naturally, Novella and Gorski — who, again, will eagerly sweep aside not only individual studies but an entire body of research as “fatally flawed,” “bad science,” “shoddy science,” and what have you for failing to meet standards they often don’t even explicitly define, and which to seem to flicker in and out of existence depending on which way a given result points — don’t mention any of this to their readers.

I want to pause for a second to address a potential response to some of my points: Aren’t I doing the same thing I’m accusing Novella and Gorski of doing? That is, I’m disregarding studies that seem to point one way, and embracing studies that point another way? After all, you can always find some methodological weakness to harp on.

I think this would be a fair criticism if, for example, I were arguing that Lisa Littman’s study provided ironclad evidence for the widespread existence of ROGD and offered us useful statistical particulars about it. But I’m not claiming that and don’t think she is either. Similarly, if I were claiming the Dutch had produced no evidence suggesting the efficacy of puberty blockers and hormones for gender-dysphoric youth, that, too, would be a very questionable interpretation of the data. But I’m not saying that: I’m saying their evidence is limited and comes from a very specific, gatekeeping-heavy context.

But I’m always open to the possibility I’m being biased, so I would welcome any feedback on this front. I do think the Turban et al study is so flawed that its evidentiary value is zero. “We have no idea how many of the kids who said they got this treatment got this treatment” is a much more severe flaw with a study, especially when you combine it with the causality issue, than “Our research findings were based on diagnostic criteria that have subsequently been tweaked a bit.” There’s no comparison, really.

7) Novella and Gorski conclude their article with a profound exaggeration of the available evidence for youth gender medicine that is completely out of step with what the evidentiary reviews conducted by major medical institutions in multiple countries have found, and make no attempt to explain how they came to such a different, more optimistic conclusion.

Here’s what they say:

The standard of care waits until children are at an age where their gender identity is generally fixed, and then phases in interventions from most reversible to least, combined with robust psychological assessments. Further, regretting these interventions remains extremely rare, and does not support the social contagion hypothesis.

At this point there is copious evidence supporting the conclusion that the benefits of gender affirming interventions outweigh the risks; more extensive, high-quality research admittedly is needed. For now, a risk-benefit analysis should be done on an individual basis, as there are many factors to consider. There is enough evidence currently to make a reasonable assessment, and the evidence is also clear that denying gender-affirming care is likely the riskiest option.

As they wrap up their article, Novella and Gorski are calling back their own misinformation: Is “gender identity… generally fixed” when it comes to kids who are just now beginning to feel dysphoric at, say, age 14? No one knows, but on the other hand: details! Is regret “extremely rare” for members of this cohort who medically transition, or for youth medical transitioners in America more generally? We have, I believe, either zero or close to zero data on this question, but again: details! Why communicate a lack of certainty when you can state, as a fact, that “regretting these interventions remains extremely rare”? It’s just really irresponsible science communication, especially, to repeat myself, given the vulnerability of the population in question, the lack of long-term evidence, and the hotly politicized nature of this debate.

Most shocking is that Novella and Gorski claim near the end of an article about youth gender medicine that “there is copious evidence supporting the conclusion that the benefits of gender affirming interventions outweigh the risks.”

Back to my Spectator article for the last time:

Whatever one thinks about these different approaches, it’s a fact that data generated from the Dutch clinic can’t be used to bolster the case for youth medical transition which takes place under very different circumstances. If kids go on blockers and hormones without good mental health and a careful assessment process, do they enjoy the solid outcomes observed by the Dutch? No one knows — and hardly anyone is trying to find out.

The lack of outcome data for gender-dysphoric youth who physically transition is one reason there has been a steady drip of news, mostly out of Europe, reflecting growing unease about these treatments. The UK has seen a complicated, slow-boiling controversy at the National Health Service’s sole provider for youth transition services, the Gender Identity Development Service at the Tavistock Clinic in London. Staffers there raised concerns about the quality of care; some argued children were being fast-tracked toward blockers and hormones in part as a result of activist pressure. Complaints from a young detransitioner who insists that she was not properly assessed, and who had a double mastectomy she regrets, culminated in a High Court ruling declaring that under-16s are unlikely to be able to consent meaningfully to blockers or hormones, making it much harder for this group to access treatment. An appeal is underway; in the meantime a convoluted process will still allow some young people to access these services with parental permission.

This spring Sweden banned youth medical transition outright at a number of gender clinics, including one at the famed Karolinska Institute, except in approved research studies. And in June last year the body that recommends on treatment methods in the Finnish public healthcare system published guidelines that emphasized the need for thorough assessment prior to the administration of blockers or hormones — stating that blockers may only be given ‘on a case-by-case basis after careful consideration and appropriate diagnostic examinations’.

These steps seem to reflect a growing realization that the holes in the research on youth medical transition are too big to ignore. Three major reviews of the literature conducted by government agencies in Finland, Sweden and the UK found an alarming lack of data supporting early treatments. The last, conducted by the NHS’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), found a grand total of five ‘uncontrolled, observational studies’ suggesting beneficial outcomes for dysphoric youth who go on cross-sex hormones. [This is actually a minor error I’m going to have corrected — NICE isn’t technically under the purview of the NHS.] But they were methodologically weak, leading the review authors to caution: ‘Any potential benefits of gender-affirming hormones must be weighed against the largely unknown long-term safety profile of these treatments in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria’. The researchers came down similarly on the strength of the evidence base for puberty blockers, describing it as ‘very low.’ Distressingly, they categorized a landmark 2011 study by the Dutch on puberty blockers as ‘at high risk of bias (poor quality overall; lack of blinding and no control group)’.

When it comes to hormones for gender dysphoric youth, it’s pretty remarkable to compare the assessments of Steven Novella and David Gorski with those of NICE.

Novella and Gorski: “[T]here is copious evidence supporting the conclusion that the benefits of gender affirming interventions outweigh the risks.”

NICE: “Any potential benefits of gender-affirming hormones must be weighed against the largely unknown long-term safety profile of these treatments in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria.”

What evidence are Novella and Gorski drawing upon that NICE missed? They should explain this striking discrepancy. And they should transparently correct their article where corrections are warranted, as well as add numerous points of elaboration and clarification. If they don’t, they will mortgage even more of their site’s long-term credibility than they already have.