The New Study On Rapid-Onset Gender Dysphoria Published In “Pediatrics” Is Genuinely Worthless

There’s a growing credibility crisis in youth gender research

I can only write articles like this because of my premium subscribers. If you find this sort of work useful, please consider becoming one, or gifting a subscription to a friend or family member or enemy:

If you’re new to my work and are interested in the youth gender debate, you also might like this article I wrote about a controversy in Leon County, Florida, this one debunking a viral study about the benefits of puberty blockers and hormones, this one debunking a Heritage Foundation study arguing the opposite, and this one evaluating Science Vs’s claim that these treatments are completely uncontroversial.

Did you hear? The theory of rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) has been seriously challenged by research published in a top-flight medical journal. Just happened, thanks to a new study in Pediatrics. As NBC News summed it up, “‘Social contagion’ isn’t causing more youths to be transgender, study finds.” Isn’t causing, full stop.

Did the study really find convincing evidence calling this idea into question? No, it did not. The study is a disaster — such a disaster it’s been torn apart by researchers who are very sympathetic to its overall argument.

If you follow this issue closely or read this newsletter regularly, you probably already know who one of the coauthors of the study is: the psychiatrist Jack Turban. Turban recently finished his fellowship and is about to start as a psychiatry professor at the University of California–San Francisco.

In recent years, there’s probably no public-facing researcher who has written or been quoted more about youth gender medicine. And it’s always in the same way: The evidence is fantastic. These treatments work. Everything’s great. Our field is helping so many kids. There’s no controversy here.

In a sworn declaration (PDF) he filed as part of a legal challenge to Arkansas’s attempt to ban youth gender medicine, Turban wrote that “all existing evidence indicates that gender-affirming medical interventions improve mental health outcomes for transgender adolescents and it would be dangerous and unethical to prohibit these medical services.” If you know anything about the present state of research on youth gender medicine, this is an absolutely astonishing thing for a supposed expert to claim — and under oath! There are plenty of studies that offer mixed at best findings about the impact this medicine has on youth mental health. Some of Turban’s own research has failed to establish a statistically meaningful link between access to youth gender medicine and improved outcomes on crucial variables like suicide attempts. (See here for more details.) This is why just about every nation or research body that looks closely into this question has found the same thing: The evidence base is alarmingly weak. Finland, Sweden, and now England have significantly tightened up how they approach youth gender medicine as a result. To my knowledge, Turban has never explained why his assessment of the research base for youth gender medicine is so different — so much sunnier — than almost everyone else’s.

His role in pushing this sort of research and this sort of message is an unavoidable part of this story. While I don’t want to make this post about him, per se, rather than the specifics of his latest study, I’d just say that if you’re curious, you can read more about his work’s many red flags here and here. Or check out this Medium post about his inability to summarize research accurately even when he was doing it for that sworn declaration (I haven’t read it closely enough to endorse 100% of the claims, but all the ones I spot-checked are legitimate). Given the outsize role he now plays in American discourse over puberty blockers and hormones for trans youth, appearing or being quoted in the New York Times and Washington Post and NPR and everywhere else, I think there are serious questions about both his research and his style of supremely confident science communication, and as far as I know, he hasn’t made any significant attempts to answer them. (PLOS ONE, the journal that published one of his more influential studies, is, to its credit, looking into questions the Oxford sociologist Michael Biggs raised about that study that would potentially reverse one of its key findings. See this post for the full rundown.) (Update/Corrected link: The text “the Oxford sociologist Michael Biggs raised about that study” originally pointed here, which is to a separate controversy irrelevant to this article. It was supposed to point here and has been fixed.)

Even setting aside these issues, some of which involve crawling around in the statistical weeds, in the past Turban has exhibited basic ignorance about the DSM-IV criteria for gender dysphoria and has grossly violated very well-established, safety-oriented standards (albeit informal and nonbinding ones) for how experts should publicly discuss youth suicide. On their own, these would be two pretty big warning signs.

The latter exchange did lead to a correction:

Which, good for Turban. But this is a bad look for a psychiatrist who presents himself as an expert on this subject. The DSM-IV pathologized mere gender diversity is simply not a claim you can make if you have any familiarity with the DSM-IV. It’s something activists say for the sake of winning an in-the-weeds fight about old research. In much of what he does, Turban acts much more like an activist than a good-faith, open-minded researcher.

So I am, suffice it to say, coming into this a bit biased against Turban. I do not really trust his research, in part because I’ve spent far too many hours poking around under its hood (I’m far from the only one to have come to this conclusion after having done so), and in part because I’ve found he’s unwilling to answer basic, Stats 101–level questions about very strong, very shaky claims he has published that have clear public policy implications. I figured I should be upfront about this bias.

We Have No Idea If Any Of The Statistics About Biological Sex In This Study Are Meaningful

On to the study itself. Here’s how Turban and his team describe ROGD:

A recent descriptive article hypothesized the existence of a new subtype of gender dysphoria, putatively termed “rapid-onset gender dysphoria” (ROGD). The ROGD hypothesis asserts that young people begin to identify as TGD [transgender and gender diverse] for the first time as adolescents rather than as prepubertal children and that this identification and subsequent gender dysphoria are the result of social contagion. This hypothesis further asserts that youth assigned female sex at birth (AFAB) are more susceptible to social contagion than those assigned male sex at birth (AMAB), with a resultant expectation of increasing overrepresentation of TGD AFAB youth relative to TGD AMAB youth. [footnotes and table references omitted throughout]

This is perhaps just a matter of sloppy writing, but it’s telling that the team can’t even correctly describe the ROGD hypothesis. Lisa Littman and others who are sympathetic to this theory definitely don’t assert that “young people begin to identify as TGD for the first time as adolescents rather than as prepubertal children” [emphasis mine] — rather, they acknowledge that kids come out as trans at different points in time but are concerned particularly with those who come out during or after puberty, which is a less studied group, and the group where they believe peer contagion is most likely to be playing a role.

Anyway, here’s Turban and his team’s methodology:

One element of the ROGD hypothesis has been understudied, namely, the sex assigned at birth ratio of TGD adolescents (ie, the number of TGD AFAB adolescents relative to the number of TGD AMAB adolescents). Although representatives of some pediatric gender clinics have reported an increase in TGD AFAB patients relative to TGD AMAB patients, there is a dearth of studies that explore this ratio in larger, national samples of adolescents. Using data from the 2017 and 2019 iterations of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) across 16 US states, we explored this component of the ROGD hypothesis and examined the AMAB:AFAB ratio among United States TGD adolescents in a larger and more representative sample than past clinic-recruited samples. Moreover, to test the assertion that youth identify as TGD because of social desirability, we also examined rates of bullying among those who identified as TGD and those who did not. We further compared rates of bullying victimization among TGD youth with rates among cisgender sexual minority youth because some have asserted that TGD youth identify as TGD because of their underlying sexual orientation and presumption that TGD identities are less stigmatized than sexual minority cisgender identities.

Turban has an exceptionally strong pre-commitment to the idea that ROGD is, in some important sense, fake or deeply overblown. He’s been open about this fact for years. So it would be shocking if he subsequently coauthored a paper saying “Whoops, there’s some evidence for ROGD.”

Sure enough, he and his team claim the data don’t support the idea of ROGD.

Turban et al.’s most important claims rely on sex ratios, or what percentages of trans kids are biologically male versus female. They argue that since in 2017 and 2019 the ratio still favored natal males, this is evidence against ROGD. I think this reasoning is totally wrong, especially given that over this period the ratio shifted in the direction ROGD theorists would predict, but the bigger problem is we don’t actually have any idea what the real sex ratios are here.

The data set in question simply asks respondents whether they are transgender and “What is your sex?” — not “sex assigned at birth” or “biological sex” or other, more specific language. So the question is how a trans person responds when you ask them their “sex.”

The consensus, before this study was published, appeared to be that there’s simply no good, reliable way to know whether a trans person answering this specific question is referring to their biological sex versus their gender identity, which, for a trans person, are likely to have opposite answers. This is a widely known issue in this data set and this sort of research. For example, one group of researchers relying on the Youth Risk Behavior Survey demurred from making any claims pegged to respondents’ biological sex in their paper: “Because it is unclear whether transgender students’ responses to the sex question reflected their sex or gender identity, this analysis could not further disaggregate transgender students.”

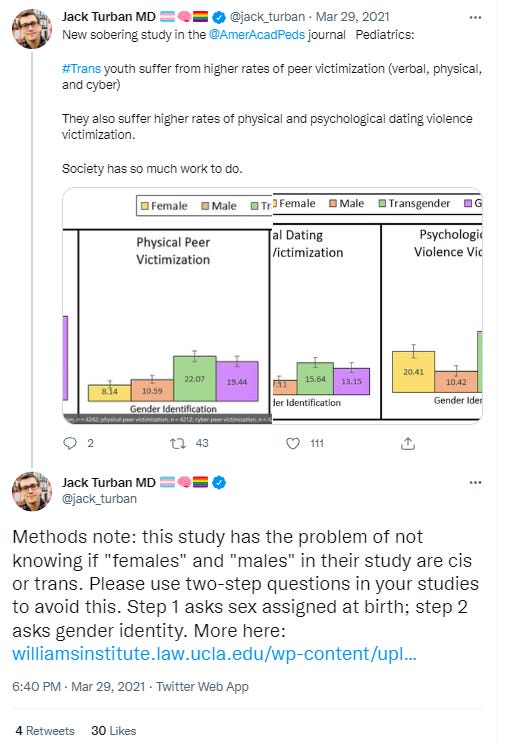

Another researcher, writing on Twitter about a different Pediatrics study in 2021, made the same point more generally: “Methods note: this study has the problem of not knowing if ‘females’ and ‘males’ in their study are cis or trans. Please use two-step questions in your studies to avoid this. Step 1 asks sex assigned at birth; step 2 asks gender identity.”

That researcher’s name? Jack Turban:

So Turban and his team are aware of this issue. But luckily, they say, there is research to back up their idea that we can safely infer that trans kids’ responses to a question about “sex” refer to their biological sex rather than their gender identity:

Youth reported their sex assigned at birth by answering: “What is your sex?” Response options were female or male. Although this question does not refer to sex assigned at birth specifically, several studies have found that TGD youth are likely to understand “sex” to be sex assigned at birth rather than gender identity, due to the foundational salience of these characteristics to their identities.13,14,15

Ah, okay. So Turban just didn’t know about these studies when he tweeted about this issue in 2021. That’s not a crime — it was a tweet, not published research. If, it turns out, “several studies” have found that usually, trans kids answer questions about their “sex” with reference to their biological sex, that would lend some credence to his and his team’s results.

Problem solved, more or less. But for the hell of it, let’s look up the three studies in question to double-check:

Footnote 13: Vrouenraets LJJJ, Fredriks AM, Hannema SE, Cohen-Kettenis PT, de Vries MC. Perceptions of sex, gender, and puberty suppression: a qualitative analysis of transgender youth. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(7):1697–1703

14: Sequeira GM, Kidd KM, Coulter RWS, et al. Transgender youths’ perspectives on telehealth for delivery of gender-affirming care. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(6):1207–1210

15: Kidd KM, Sequeira GM, Rothenberger SD, et al. Operationalizing and analyzing 2-step gender identity questions: methodological and ethical considerations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(2):249–256

Wait a minute… none of these studies even addresses the question of how trans kids answer a query like “What is your sex?,” let alone offers data supporting Turban’s and his team’s claim. (Seriously; they don’t come close. The first one concerned Dutch kids, anyway, so it seems unlikely the conversations took place in English.) I emailed Pediatrics to ask about this discrepancy and will update this post if and when the journal gets back to me, but unless Turban and his team have other studies up their sleeves that they failed to cite, “several studies have found that TGD youth are likely to understand ‘sex’ to be sex assigned at birth rather than gender identity” appears to be a wholly made-up claim. In a top-flight medical journal!

This is not a small thing. If even a relatively modest percentage of kids interpreted “sex” to mean “gender identity” rather than “biological sex,” it would massively change the results: The authors write that “In 2017, 2161 (2.4%) participants identified as TGD, with an AMAB:AFAB ratio of 1.5:1. In 2019, 1640 (1.6%) participants identified as TGD, with an AMAB:AFAB ratio of 1.2:1 [bolding mine].” You can do your own math if you’re so inclined, but it just wouldn’t take much to nudge things toward a very different storyline.

It turns out we have pretty solid evidence to suggest that some of the trans kids who answered this question did so with reference to their gender identity rather than their biological sex. Not long after the study went up, Michael Biggs let me know that he submitted a critical comment about it to Pediatrics that was rejected just an hour later — a surprisingly short time for such a rejection.

You can read his comment in full here, but one of the cleverest things he did was take advantage of the fact that the data set includes height as a variable:

Predicting height separately for each sex, OLS regression (adjusting for age and race) reveals that transgender respondents who identified as male were on average 2.5 cm shorter than non-transgender male respondents (95% CI: 1.3 … 3.8 cm, total n = 87,568). (There was no discernible height difference between transgender respondents who identified as female and non-transgender female respondents.) This height difference is evidence that some of the transgender respondents who identified themselves as male were natal females.

This means that if biological sex had been reported accurately, a number of members of the “male” category would instead be in the “female” category, which would nudge everything in exactly the direction that is unfriendly to Turban’s and his colleagues’ theory (that’s if you accept their logic).

What’s the exact percentage of kids who answered the question with reference to gender identity? There’s no way to know. But again, it probably wouldn’t take that many such responses to completely ruin Turban’s and his team’s argument about sex ratios.

As I was completing this post, another critique of this study appeared online, this one by a group of researchers who are very friendly to Turban’s overall political project, and who are very skeptical of ROGD. They dug deeply into the actual data in a way I didn’t during my brief time working on this piece, and they noticed that the authors got a basic thing very wrong: a “data reporting error that severely misrepresents the robustness of the sample”:

Turban et al. state that their estimates of the AMAB:AFAB-ratio are based on 16 states in the abstract, 15 for 2017 and 15 for 2019 (Delaware in 2017 only and New Jersey in 2019 only) as shown in the caption for Table 1. However, only 10 states fielded the SOGI [sexual orientation and gender identity] module in 2017, and of them only 9 had publicly available data (Massachusetts does not provide permission for the CDC to share their data). Similarly, only 14 states with publicly available data fielded the SOGI module in 2019. Under these circumstances, the trend analysis is comparing subsets of trans youth from different states and any differences are likely due to sampling bias making the trend analysis invalid. [footnotes omitted here and below.]

More:

Beyond issues with the trend analysis are issues with the individual point estimates for the AMAB:AFAB-ratio. For 2017 and 2019 less than one-fifth and one-fourth, respectively, of the 50 states and five territories in the United States are included in the analysis. Table 1 shows the high variability of the AMAB:AFAB-ratio between states and within states across time points. Much of this variability is driven by the sample size; for instance, in the Rhode Island sample between 2017 and 2019 the AMAB:AFAB-ratio inverted from 0.8 to 3.0, based on TGD youth samples of only 39 and 16 persons, respectively. In comparison to Rhode Island, Maryland dominates the sample for both years. Specifically, Maryland comprises 67% of the sample (1547/2302 persons) in 2017, and 40% (711/1790 person [sic]) in 2019. To show the sensitivity to state inclusion, we recalculated the AMAB:AFAB-ratio without that state for 2017 and 2019, and found 1.2 and 1.1, respectively compared to the 1.5 and 1.2 in the authors [sic] original analysis. Because the authors methodology did not account for oversampling, their analysis provided biased results and shifted the “national” estimate that is driven by a single state. Additionally, the analysis neglects the survey sampling design. YRBSS state surveys are two-stage cluster samples and the data include weights that allow for state-level representative analyses. We have written elsewhere that such analyses are suboptimal for estimating transgender populations when one-step gender identity measurements are used, however; to overlook the sampling schema precludes the possibility of state-level representative estimates, making further extrapolation to the entire US dubious. This critique also applies to the pairwise comparative analyses in Tables 2 and 3 between trans, cisgender sexual minority, and cisgender heterosexual youth which similarly fail to account for survey sampling design and clustering by state. Providing details of any approach regarding accounting of sampling schema, if any were indeed utilized, would have benefitted the analysis. Lastly, the analysis becomes more problematic when one notes that the few states included are not a random sample of the US states and territories, but instead show a concentration of states in the Northeast, and a smaller group in the Midwest with remaining states having no neighbors that also collected data on TGD youth[.]

If you don’t understand every word of this, that’s fine. But the point is that this data is incredibly flimsy. It’s a nonrepresentative sample as it is, and even within that nonrepresentative sample, Maryland completely dominates the scene. We cannot trust these results at all. This data can’t be used to make any claims about any trends concerning trans people in the United States.

Even If There Weren’t Questions About The Sex Ratios, This Study’s Logic Makes Very Little Sense

By this point, you should know that this study is genuinely worthless for the sake of addressing the ROGD controversy. If that’s all you need to know, go in peace. But I do want to highlight just how shoddy the logic of this work was throughout. Even if all the aforementioned issues didn’t exist, this study wouldn’t have come close to engaging meaningfully with the ROGD theory.

Turban and his team, remarkably, claim that their data appear to show a much lower percentage of kids identified as trans in 2019 than in 2017, and then gloss over this finding despite the fact that it runs contrary to what’s being observed almost everywhere else. In the aforementioned sworn declaration (PDF, again), Turban himself mentioned, without dispute, the phenomenon of “the higher rates of adolescents openly identifying as transgender.” The debate among experts really hasn’t been about whether this rate is going up — in fact, I can’t remember anyone even questioning that finding, to be honest. Rather, the debate has been about why. In his declaration, Turban really seems to take it as a given that the rate is going up, and offers an explanation that runs contrary to the ROGD narrative: “Transgender young people are for the first time growing up in environments where transgender identity is not as stigmatized, making it much easier for them to come out when compared to transgender adults plagued by anxiety due to decades of living in societies where being transgender was not recognized or accepted.”

Then, a little more than a year later, he publishes research seeming to show the exact opposite, and just breezes past it with no explanation. “Transgender young people are for the first time growing up in environments where transgender identity is not as stigmatized,” and as a result… fewer of them are identifying as trans? Huh? This absolutely screams out for an explanation. There’s no explanation, because Turban and his team didn’t take seriously the task of analyzing their data and fitting it into past work on trans youth. The whole point was to produce something that looks enough like evidence against ROGD to further their preestablished agenda of fighting this hypothesis. That’s my belief, at least, and I think it’s consistent with the standards of rigorousness on display here.

Turban and his team are in a bit of a bind with regard to clinical samples, which do fuel a lot of ROGD theorizing because just about everywhere, referrals are increasing and getting more and more female. (It’s not that ROGD is the only explanation for these patterns, but they are compatible with ROGD.) The authors, again, just sort of breeze past both how common this finding is, as well as the sheer magnitude of what has gone on: “Although representatives of some pediatric gender clinics have reported an increase in TGD AFAB patients relative to TGD AMAB patients,” they write, “there is a dearth of studies that explore this ratio in larger, national samples of adolescents.” Here there are a grand total of two citations, whereas for the made-up claim about the sex question, they managed three.

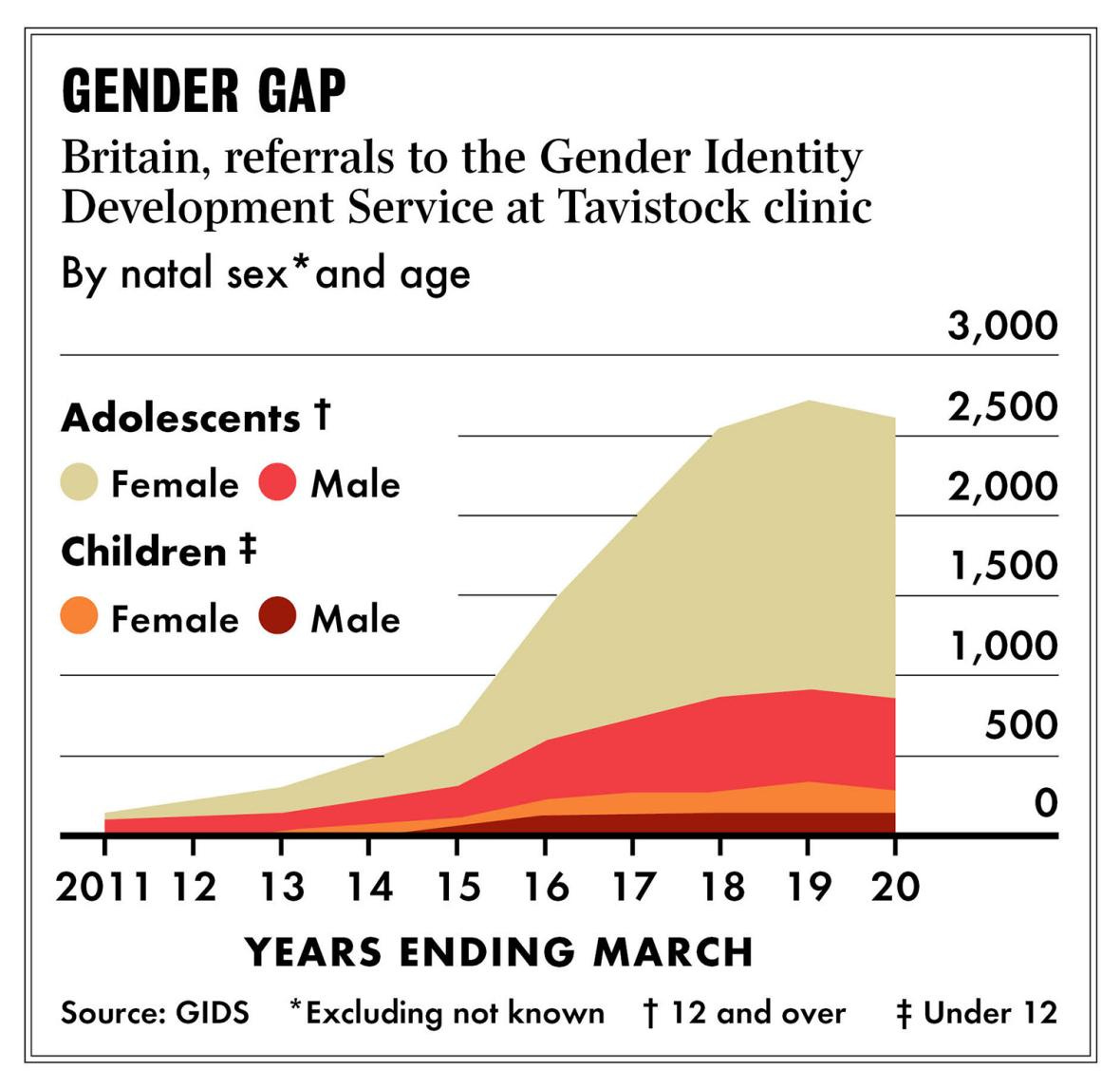

In fact, many clinics on two different continents have all noticed the same thing. Here’s a graph from the British Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), via a (paywalled) Sunday Times article by Janice Turner:

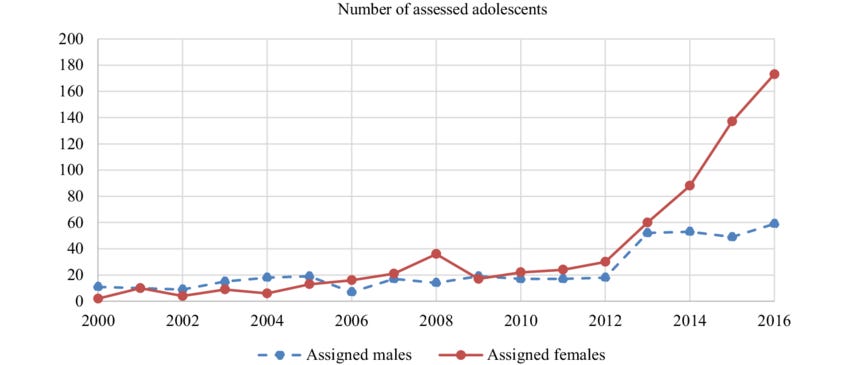

Here’s a similar graph from “the Dutch Clinic” in Amsterdam (I couldn’t find one that ends more recently), via this study:

This clinic from California reported that from 2015 to 2018, the number of referrals per year tripled, and “73% were assigned female sex at birth,” which is quite a skew (I didn’t read the whole thing carefully, but I don’t think the authors included data on whether that percentage increased over time).

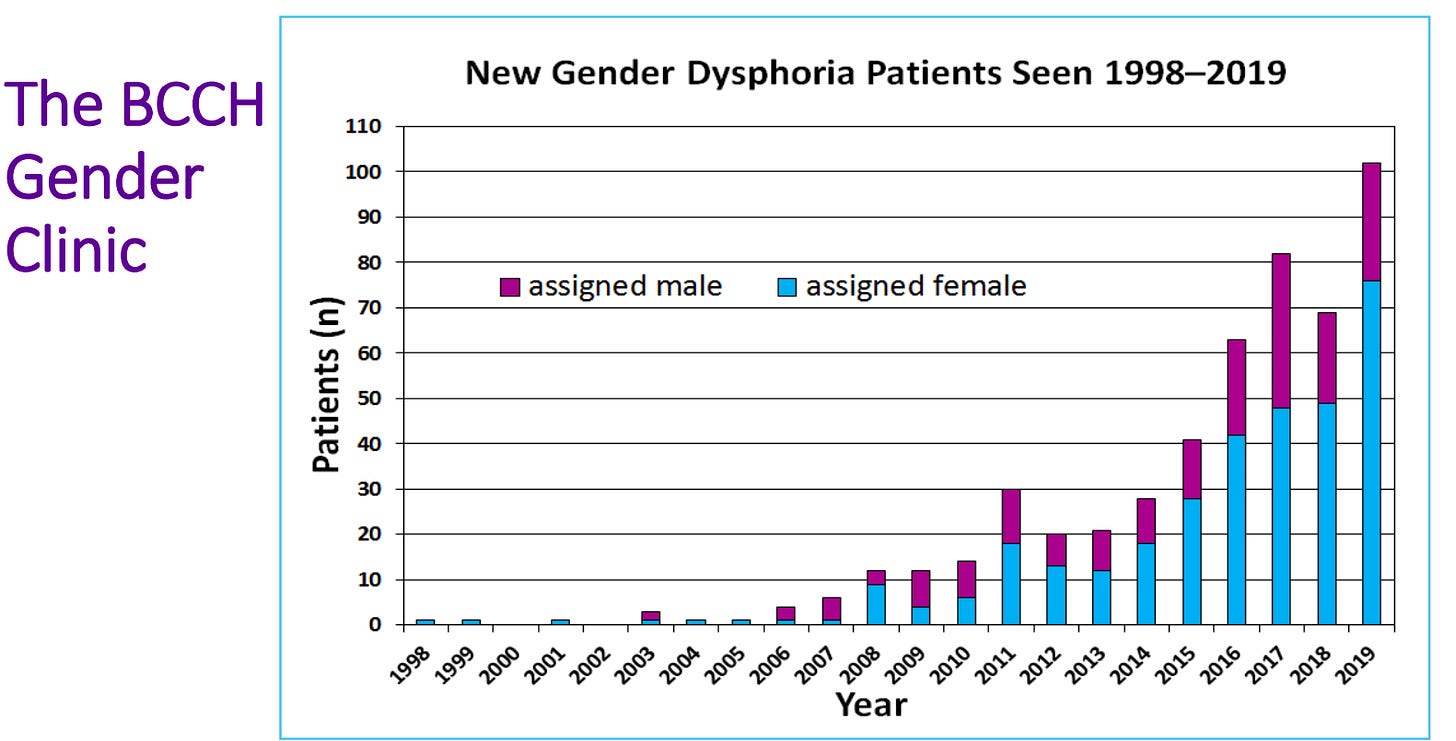

And here’s a graph from the Gender Clinic at British Columbia Children’s Hospital, via a public event put on by Trans Youth CAN!:

Elsewhere, at a Spanish youth gender clinic, “Over the 18-year period [of the study], the number of referrals increased considerably, more assigned natal female minors and children were seen[.]”

It appears to be the same situation everywhere there are gender clinics that report their data: way more referrals from year to year, with the trend growing more female. The real debate, again, is why.

Even if national-level statistics look different — which Turban and his colleagues haven’t come close to proving — would that necessarily tell us anything? Of course in general there are a lot of contexts where you’d prefer a representative sample1 over a clinical one. If you want to know what the “average trans person” thinks or does, or what health challenges they face, you’d prefer a nationally representative sample to a clinical one. But among the people who believe in the ROGD hypothesis and are worried about it, their top concern, by far, is kids undergoing unnecessary and harmful medical procedures. So they’re much more concerned about supposedly ROGD kids being put on blockers and hormones by irresponsible clinicians who don’t properly assess them than they are about, like, kids cycling through new pronouns on TikTok. If only a subset of kids are affected by ROGD, that could show up in the clinical data but not zoomed-out national data. So if your goal is to debunk ROGD, I don’t think you can fairly ignore what’s going on in clinics everywhere, which the authors do.

The Authors’ Other Claims Are Pretty Shallow And Badly Misrepresent The ROGD Argument

Turban and his colleagues made doubly broken claims about sex ratios among American trans youth. I say “doubly broken” because there’s an issue both with how the question was asked and with the fact that the data is about as unrepresentative as can be. Either problem on its own would seriously threaten the validity of this research; combined, this is a disaster, and an embarrassment for Pediatrics.

The study’s subsidiary arguments aren’t much better. To respond to the claim that some kids embrace a trans identity because it gives them community and/or because it feels safer than acknowledging that they’re gay, the authors note:

…TGD youth were more likely to be victims of bullying and to have attempted suicide when compared with cisgender youth, which is consistent with past studies. Our additional analyses reveal that TGD youth experience significantly higher rates of bullying than cisgender sexual minority youth, who themselves experience significantly higher rates of bullying when compared with cisgender heterosexual youth. These exceptionally high rates of bullying among TGD youth are inconsistent with the notion that young people come out as TGD either to avoid sexual minority stigma or because being TGD will make them more popular among their peers, both of which are explanations that have recently been propagated in the media. Of note, a substantial percentage of TGD adolescents in the current study sample also identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual with regard to their sexual orientation, which further argues against the notion that adopting a TGD identity is an attempt to avoid sexual minority stigma.

This is a misunderstanding of… well, everything. Let’s use an example we know is driven by social contagion to make this point: goths. I am not aware of any high-quality polling on goths, let alone representative polling, but it seems safe to assume goths are bullied more often than non-goths. Imagine the argument “You’re claiming being a goth is socially transmitted, but that makes no sense, because why would someone choose to be a member of a group that is bullied?” This would be supremely silly, because the sort of kid who is entering gothdom is probably already facing some level of ostracization or bullying or other social issues. That’s why the goth identity appeals to them! Then, once they’re a goth, it can both be true that they’re a member of a group that is looked down on by other, more popular cliques in their school, but also that membership in the group gives them a sense of meaning and social belonging they previously lacked.

The problem is failing to make the right comparison. The question isn’t whether goths are more popular than non-goth; it’s whether an already unpopular non-goth might become a bit more popular, or at the very least gain a modicum of belonging and community, by putting on those weird dark clothes and mascara. (Plus, there’s some legitimately awesome music.)

I am not directly comparing being a goth to being trans, of course — I’m using an example that we know is 100% driven by social contagion rather than latent biological factors to make the point.2 But to engage honestly with the ROGD hypothesis would be to acknowledge that Lisa Littman and others have never presented this as, like, a video game character selection screen: “Instead of choosing to be popular cisgender kids who captain the football team, our thesis is that kids choose to be bullied trans teens instead.” That would be ridiculous. The whole point of the ROGD hypothesis is that it is more likely to affect kids who are already lonely and disillusioned, and that for kids going through that sort of stuff, embracing a trans identity might bring with it the promise of some degree of social and psychological relief.

Maybe ROGD’s proponents are wrong about this! But if you want to argue in print that they’re wrong, you need to engage with the actual substance of what they’re saying, not a caricature of it. And if you go online it’s immediately obvious that yes, kids find community and support when they come out as trans, even as one component of that group membership often involves complaining about bullying, adults not understanding them, and so on. It should be neither complicated nor controversial to claim that a lot of teenage subcultures are structured in exactly this way, where part of the point is feeling like an insider among outsiders.

It’s not quite as silly, but I also think Turban and his team are also misunderstanding the homosexuality argument in a pretty willful way. My understanding has always been that the argument is two-pronged: First, in some youth settings it might be perceived as cooler or higher-status to be (say) a trans boy than a cisgender lesbian, which could nudge kids in that direction. (It is plainly true that in some progressive adult settings, trans guys are seen as “higher status” than cisgender lesbians, and trans women as “higher status” than cisgender gay men, so I don’t see why we should be skeptical this could be true among some youth as well.) Second, due to internalized homophobia (and misogyny), some females (especially) might interpret homosexual feelings as evidence they are trans. It’s not uncommon for youth gender clinicians to encounter 12- or 13-year-old natal female patients who say things like “When I picture myself kissing a girl, I see a boy kissing a girl.”

These are kids with no real-world experience with sex or romance, and they’re immersed in a very complicated, ever-swirling vortex of hormone-addled ideas about sex, gender, identity, status. The ROGD hypothesis is that in some cases, to the extent anyone has a “true” or “latent” or “innate” identity, they’re really lesbians, but just don’t feel comfortable landing at that conclusion. Whether or not this theory is true — I think it is in some cases, in part because I’ve read and listened to firsthand accounts from kids who say it’s happened to them and trans-affirming clinicians who insist it’s a real phenomenon — Turban’s and his team’s approach of simply looking at zoomed-out bullying data doesn’t engage with any of its actual meat. It goes without saying that “some trans kids identify as gay or lesbian” is not a response to the argument that other kids adopt a trans identity as a result of internalized or external homophobia.

So throughout their study, Turban and his colleagues are responding to strawman arguments that no one in the ROGD camp is really making.

A Final Note On Social Contagion

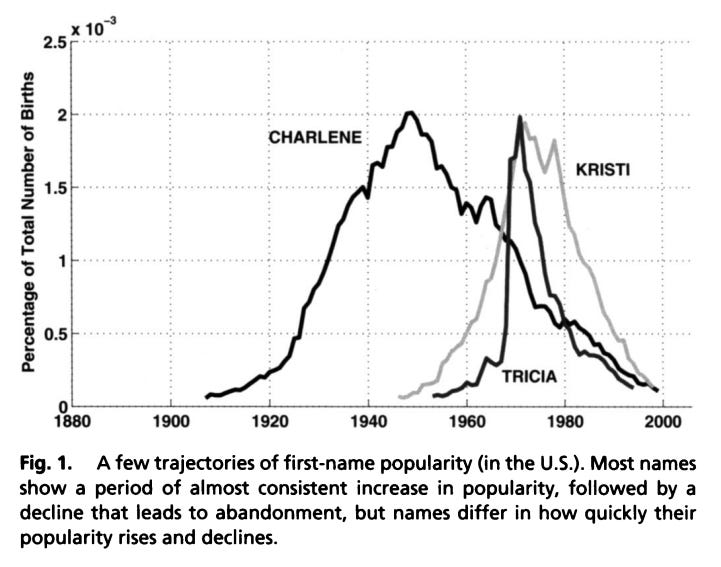

Gabriel Rossman, a sociology professor at UCLA, sent me a very useful email running down his thoughts on this study. You can read it in full here, but this is the bit I found most interesting, in which he grants the possibility of an observed decline in trans identity but points out that simply grabbing two points on a graph of a phenomenon’s prevalence can’t tell you anything about whether or not it’s a “social contagion” in the sense that people are arguing here (image inserted by me):

Ok, so here’s the [aspect of the study] that’s most relevant to my own research agenda. To call something a social contagion, the product of social influence, a fad, etc. does not imply that it will always and continuously rise. If that was the case all of us would still be doing the Macarena while swinging a hula hoop and being deathly afraid of the mad gasser of Mattoon.

The classic example of fashions in the sociology literature are baby names, which rise and then fall. See Lieberson’s Matter of Taste (2000). Indeed, Berger and Le Mens PNAS 2009 shows that names that rise quickly also fall quickly.

You can check any given name using Social Security data and see that many of them have time trend graphs resembling a lone mountain. For instance, here is “Caitlin” which certifies a woman as a millennial almost as reliably as checking her driver’s license for her year of birth.

https://www.wolframalpha.com/input?i=name+caitlin

Saying that something spreads by social influence or is a social contagion does not mean it never falls. But it does strongly imply that at some point it spread via exponential growth. And we have evidence for periods of exponential growth in both the Tavistock clinical data (which shows growth from 2009 to 2019, with the most rapid growth being 2014 to 2018) and the age-period-cohort analysis Danya Lagos published recently in American Journal of Sociology [data here]. Note that the Tavistock data suggests that trans began to level off around 2018.

Turban et al. Pediatrics shows trans identification at two time periods and shows decline between them. But this does nothing to establish that trans identification did not experience rapid growth during an earlier period. Showing a decline does not show that something does not spread via social influence, only that it has gone past its peak popularity. Saying trans youth identification declined from 2017 to 2019 therefore trans is not a social contagion is like showing disco record sales declined from 1978 to 1980 and therefore disco was not a music fad.

Finally, one note on social contagion. Given the evidence for exponential growth in earlier periods, I think it is indisputable that trans identification spread via a process of social influence. The meaningful question is not social influence yes or no, but social influence of what to whom. One interpretation can be that there have always been about 2% of the population, including many natal females, whose true latent identity is trans or nonbinary but that this had been suppressed until a critical mass of acceptance, role models, etc. allowed people to reveal their true natures. That is, trans is like being left-handed, which has an underlying neurology but which as a social fact increased after schools stopped forcing lefties to write with their right – but then it stopped, with basically zero neurological righties adopting leftie [sic] identity and behavior. Another interpretation is that the spread of trans identification is not meaningfully limited to a population for whom it describes some latent essential nature, but spreads more broadly. In this model, trans is like the hula hoop. Or perhaps it is like left-handedness for the rate and population we saw until about 2007 and like the hula hoop for the higher rate and novel populations we have seen since then.

People tend to think of only the hula hoop model as “social contagion” but from the perspective of a diffusion specialist, both are. That is, a social influence process does not have to be just social influence to be social influence. Hybrid corn seed spread across Iowa in the 1930s because it spread by word of mouth and because it was a great crop. I like Lagos’s concept of “biographical availability” as a theoretical frame broad enough to encompass both models. For the left-handedness model, biographical availability could be something like “I have always felt myself to be a member of the other gender and that my body is wrong for me and now I see all these role models showing how this is a meaningful concept, there’s a way to adopt this as an identity, and there is decreased stigma, gatekeeping, etc. for doing so.” For the hula hoop model biographical availability could be something like “I feel dissatisfied and anxious and I really don’t like the changes my body is going through and don’t feel I can attain the standards of femininity our society holds up and my friends in-person and online say it’s because I’m really a transman and here’s what you have to tell people to get on T.” Or, for a different population, it could be that a critical mass of consumers for a certain type of pornography means there’s more of that pornography produced and available, which in turn habituates more people to the paraphilia embodied in the pornography. (The porn example is technically a network externality, but network externalities are a pathway for social influence, which is not limited to just word of mouth but can encompass any density dependent process). Both the left-handedness and hula hoop models are consistent with the idea that as trans becomes more common, it becomes more biographically available and therefore spreads socially, though the two flavors of the social influence model do have different implications in other respects. For one thing, the left-handedness model implies it should rise to a certain level and then stabilize. For it to rise and then drop is more compatible with a model of pure culture, absent any resonance with latent nature, for some nontrivial fraction of the adopters.

This all makes sense to me. A lot more sense than Turban and his colleagues’ deeply shoddy study.

Questions? Comments? Speculation about whether interest in my newsletter reflects a genuinely innate biological phenomenon or a regrettable and soon-to-be-forgotten social contagion? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

Image: St. Paul, Minnesota. March 6, 2022. Because the attacks against transgender kids are increasing across the country Minneasotans hold a rally at the capitol to support trans kids in Minnesota, Texas, and around the country. (Photo by: Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

It’s just hard to get truly representative samples for a lot of minority groups, including trans people. Often, the best you can do is representative-ish.

Though with the GWAS revolution, you never know — watch this space for breaking news about the newly discovered genetic underpinnings of going goth.

Another thing that's weird about this.

Do trans activists need to fight the ROGD idea? Couldn't you just say "some people are trans, but some people are misdiagnosed as trans when they have other issues. It's important to differentiate these groups."

I'm sure everyone in here believe in, for the lack of a better term, "people with cancer rights." But wouldn't it be reasonable to check if someone actually has cancer before giving chemo?

Just a bizarre paper.

I think you missed something though. When Turban says this:

"Of note, a substantial percentage of TGD adolescents in the current study sample also identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual with regard to their sexual orientation, which further argues against the notion that adopting a TGD identity is an attempt to avoid sexual minority stigma."

Many trans-identified people who are opposite-sex attracted describe themselves as either "gay" or "lesbian" on the basis that they are "trans men" attracted to men, or "trans women" attracted to women. Similarly the trans people who describe themselves as "straight" may actually mean attracted to people of the same sex. So unless this was asked in such a way as to ascertain what they meant, this also doesn't tell you very much, and certainly doesn't rule out the idea that a large set of the ones self-identified as "straight trans" were actually gay or lesbian prior to transition.