The Heritage Foundation’s Paper On Puberty Blockers And Hormones Is Quite Bad

So naturally it went viral in conservative circles

Recently the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, published a report by Jay P. Greene about puberty blockers and hormones for trans youth. Greene claimed to have found, as he put it on Twitter, that “easing access to puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones has actually increased youth suicide rates, contrary to the claims of the Biden admin, advocates, and flawed prior research.”

That’s an extremely strong causal claim for a social scientist to make. A scary one. Unsurprisingly, it’s being spread far and wide by right-wing commentators eager to score points in the culture war — it’s very unfortunate that that’s what it is right now — about youth gender medicine. Some big conservative outlets picked up the study, and they tended to echo that same causal language:

But Greene’s report doesn’t show anything like that — it’s very, very shoddy research. I don’t think this paper warrants the sort of in-depth debunking I’ve done elsewhere. Its flaws are so evident, and it swings and misses so badly with regard even to being about the thing it purports to be about, that I hope I can keep this brief (I usually fail). I’m just going to point out how broken the methodology is and address some of Greene’s responses to his critics, myself included.

Greene’s Argument

Greene’s argument is basically this:

1. Some states have provisions allowing for minors to make their own healthcare decisions in certain circumstances, which could allow them to access puberty blockers or hormones.

2. If, since youth gender medicine became available in the United States, we compare the suicide rates in states with versus without these provisions, while controlling for other potentially confounding factors, we can test the popular hypothesis that youth gender medicine reduces suicidality.

3. When we do this, we see that actually, in states with youth gender medicine access provisions, the suicide rate has gone up over this period, compared to in states without such provisions.

4. Therefore, access to blockers and hormones increases youth suicide.

Before I get into the details, I should say that I’m extremely skeptical that we could confidently attribute any change in a state’s suicide rate — no matter how carefully measured and no matter how many confounders were controlled for and no matter which direction it pointed — to access to youth gender medicine (or a lack thereof) in particular.

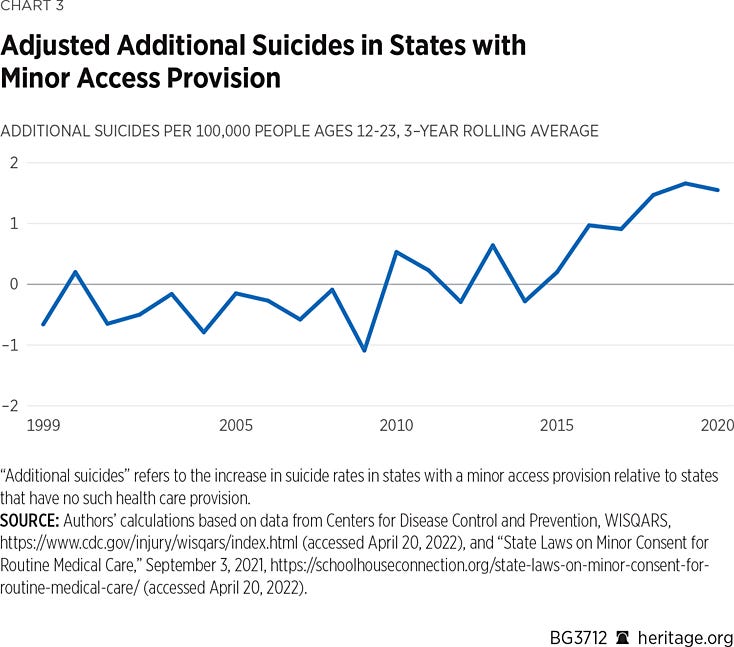

That’s especially true here. Once you adjust for potential confounders, all the action concerns a difference of 1–2 suicides per 100,000 young people:

Any suicide is a tragedy, of course, but the differences here are small, in a statistical sense. And the suicide rate, for youth and adults alike, jumps around for so many reasons — there’s in fact no expert consensus on exactly why. Nothing better highlights how little is known about the suicide rate than the fact that mental health experts were at least somewhat divided on whether, during the pandemic, it would go up or down (it appears to have gone down, thankfully). If there’s at least some before-the-fact uncertainty about how something as world-historical as a massive pandemic is going to affect the suicide rate, why should anyone have any faith that experts can suss out the precise reason one group of states has a 1–2 per 100,000 higher suicide rate than another? (Yes, yes, I know Greene controlled for some stuff — but obviously he doesn’t come within light years of controlling for everything you’d need to control for to be confident that the above chart can be traced to one particular policy and set of medical procedures. More on that soon.)

Getting a bit more specific can help explain why we should be supremely skeptical that it makes sense to look at puberty blockers and hormones as a driving factor here. Transgender identification is on the rise among young people, but there still just aren’t that many trans kids seeking blockers and hormones, relatively speaking. And of the ones who are, only so many of them are seriously suicidal in the first place, meaning that at the outset, we have some reasons to be skeptical of these treatments, on their own, having noticeable effects on state youth suicide rates. Greene calls his approach a “superior research design” to other, prior attempts to evaluate the effects of this medicine, but it’s fundamentally not credible. (If anyone reading this is new to my work, I should say that I think liberals chronically overclaim about the strength of the evidence supposedly linking youth gender medicine to good outcomes, and I did deep dives on the subject here and here.)

Above is the supposed smoking-gun chart. And here are the states and which categories they fall into:

Here’s how Greene justifies his approach:

There is also a lack of precise information on where cross-sex medical interventions are more readily available to adolescents. A reasonable proxy for that data is to identify the states that have a legal provision allowing minors to access routine health care without the consent of their parents or guardian, at least under some circumstances. In states that have those provisions, puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones should be more easily available to teenagers.

No, this is not a reasonable proxy, for three reasons.

First, during much of the time period in question — Greene is clear that he sees the trend emerging from 2010 on — it simply wasn’t the case that these treatments were widely available in most of the country. Take five of the states on the list: Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. This Cosmopolitan article from 2014 was written by “the only pediatric endocrinologist in the only transgender youth clinic in the Southwest” at that time, which is located in Dallas. If in 2014 there was only one transgender youth clinic in the entire Southwest, then of course it doesn’t matter what the minor healthcare access laws were in those states — hardly any young people were able to access blockers and hormones at the time. (If instead of one transgender youth clinic in this giant region there were, say, three or four, that wouldn’t change my argument much.) And while the number of youth gender clinics has increased quickly, it takes a while for them to ramp up — it’s not like in 2016 or 2017, the Southwest was suddenly an all-you-can-inject hormone buffet for trans youth. (If you look at the suicide stats in those states during the period in question — credit to Dave Hewitt, whose work we’ll get to, for assembling this chart — you’ll see that in all four, the suicide rate jumped significantly from 2010 to 2020. That means Greene’s result is being driven in part by changes in suicide rates in states where, for most of this span, there was very little youth gender medicine going on, let alone youth gender medicine minors could access without parental permission.)

The same logic applies in many states on the right side of that chart. No one actually thinks there was a major presence of youth gender clinics in Wyoming or Idaho or Indiana between 2010 and 2020. I doubt Human Rights Campaign’s tracker is fully up to date, but as of today it lists but a sole youth gender clinic in those three states.

Second, most of the laws in question only allow minors to access their own healthcare in very specific situations. We know Greene is extracting his information about the state laws from SchoolHouse Connection because he tells us he is, and if you click over you’ll see this description: “This document includes 34 states, and the District of Columbia, with laws allowing minors who are living on their own, including unaccompanied minors experiencing homelessness, to consent for routine health care, which should include vaccinations unless explicitly exempted.”

In a few outlying cases, minors who have reached certain ages can make their own medical decisions, full stop, but this isn’t the norm: These laws really are mostly about homeless and emancipated minors. For example, the law in Texas is that “A child may consent to medical, dental, psychological, and surgical treatment for the child by a licensed physician or dentist if the child is 16 years of age or older and resides separate and apart from the child’s parents, managing conservator, or guardian, with or without the consent of the parents, managing conservator, or guardian and regardless of the duration of the residence, and is managing the child’s own financial affairs, regardless of the source of the income.” Similar deal in Utah, where “An unaccompanied homeless minor who is 15 years of age or older may consent to any health care not prohibited by law.” Okay, so this applies only to a very tiny percentage of kids, and while Greene’s analysis is in theory about both blockers and hormones, it’s worth noting that these kids would already be approaching the end of their eligibility period for blockers, anyway, if not already past it.

I’d argue that in many of these states, during much of the 2010-2020 period in question, the number of kids who would actually be eligible to seek blockers and hormones on their own, and who would want to do so in the first place, is unlikely to be far from zero. It’s just math. Roughly: Take a state’s total population, multiply that by the percentage that are emancipated and/or homeless minors, and multiply that by the percentage of the overall population that are trans youth seeking to physically transition.

Greene openly acknowledges that there’s a wide range from state to state in what these laws say, but then he just sort of brushes this aside, treating it as a minor issue and lumping together all the states with any such provision, despite the fact that in many of them, only a small slice of kids will ever be able to seek their own medical care, and that even these kids will likely be too old for blockers, anyway. This is an exceptionally crude method of carving up the states, roughly the same class of crudeness as the dichotomization shenanigans I discussed here.

Third and finally, just because a state has a provision granting kids the ability to seek their own medical treatment doesn’t mean a medical provider will dispense it! There’s huge variation across clinics in how much “gatekeeping” occurs. While “informed consent” is increasingly common for adult clinics, it isn’t universal, and trans people have numerous stories about being denied treatment by clinicians who thought they “weren’t trans enough,” had too many other psychological problems, and so on. The point here isn’t to litigate the right approach but simply to note that it’s one thing to say that the law allows some teenagers to make their own medical decisions without any adult’s say-so, and it’s another to say that an actual, real-life trans health clinic in 2016 would actually prescribe them hormones. The further back in time you go, the fewer informed consent clinics there were — many clinics were happy to say no to adults, or to impose onerous restrictions, so why would they be less likely to do this in the case of a (possibly homeless) minor?

Summing all this up, for any given state, the question of whether the presence of a provision allowing youth to make their own medical decisions would enable some youth actually to access blockers or hormones would depend on:

—whether the youth in question qualified for the provision (in most cases they would need to be homeless or emancipated, meaning the vast majority of youth would be excluded from even hypothetical access to these treatments without parental consent)

—whether there was a gender clinic close enough for the youth in question to access it, and during the earlier years of this time span (against, 2010-2020) it would probably have to have been over multiple appointments, meaning in many cases the geographical distances and other logistical challenges would be too great

—whether, if there were a gender clinic the young person could go to (probably for multiple required appointments), the gender clinic would agree to put the young person on hormones.

My contention is that for much of the time period in question, in many of the states on the right side of that chart, the presence or absence of one of these laws would make almost no difference in the number of minors able to access blockers or hormones. We’re talking absolutely tiny numbers. This means that any claim that these policies affected the youth suicide rate relative to states which lacked them — and that those differences can be attributed in particular to access to blockers and hormones — should be met with stiff skepticism.

Of course, actually getting a grasp on the numbers — on which gender clinics had which policies when, how realistic it was for emancipated Idahoan teens to access hormones in 2014 (not very, I can confidently guess!), etc. — would require an overwhelming amount of research. Not gonna do it. But in addition to lumping together very different state laws on minor access to healthcare, Greene can only make his argument by simplifying and abstracting the daunting landscape that would have been faced by any solo trans kid seeking these treatments. And then he dispenses with any sort of caution, claiming that “easing access to puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones has actually increased youth suicide rates.” Full stop. Causal language.

That’s really irresponsible! We’re talking about young people and suicide. There’s no area where we should be more careful.

One final point worth highlighting: Greene says that one strength of his approach is that it appears to be more or less random which states do and don’t have provisions for minors seeking their own healthcare. The right side of the above chart includes both Texas and Massachusetts, which are as different as two states could be.

If states did randomly fall onto one side of that chart or the other, in theory this could make it easier to attribute any differences in subsequent outcomes to the existence of these laws. But the problem is that it could still be the case that the states are accidentally clumped together in certain confounding ways. That is, the 17 states without youth access provisions could share unobserved characteristics that somewhat shielded them from the national rise in youth suicidality observed since 2010, while the 33 states with such provisions could share unobserved characteristics that rendered them somewhat more susceptible to it.

Let me illustrate this with a totally out-of-left-field example from the first thing I noticed about the two groups of states: that one of them contained Texas and California, the two biggest states (by population) in the country. That made me wonder how many of the biggest cities by population fell on the left side of the table versus the right. With some help from World Population Review, I marked up the table to indicate how many of the 15 most populous cities are in each state (in almost all cases the answer is zero, of course):

Of the 15 biggest cities in the country, 12 sit in states with minor access provisions. Maybe, for whatever reason, big urban areas were more susceptible to increases in youth suicide. Greene didn’t control for that, so that could account for some of the observed differences.

I’m completely making that up, but my point is you could pick basically any variable potentially connected to the youth suicide mystery, and there’s a decent chance you’ll find some difference between the two groups. That’s because there are only 50 states, and only 17 of them in one category. There’s such heterogeneity between states that it’s very unlikely that if you carve them up this way, the two groups will be truly equivalent in all the ways that matter for the subject at hand. Along those same lines, five of the six biggest states are on the right — maybe similar logic applies at that level.

Greene does control for some variables, such as states’ baseline suicide rates. But that’s not enough. Literally any other unobserved, unaccounted-for factor correlated with the rise in youth suicide could also partly account for the difference that drives Greene’s conclusion, and nowhere does he explain why he’s confident he can rule out that possibility.

Greene Responds To His Critics

On his own website, Greene wrote:

Other than name-calling with words like “misleading,” “crude,” and “shodd[y],” Singal has two seemingly substantive objections to offer. First, he claims “this isn’t even about blocker [sic] and hormones — it’s about which states have lower ages of medical consent. Then he says ‘Well, around the time blockers became available, the suicide rates go up.’ This is an exceptionally crude approach.” Second, he embraces a criticism expressed by Elsie Birnbaum that it is ridiculous to describe states like Texas and Utah as having “easier” access to these drugs, adding: “This is a good catch and should immediately cause anyone with any knowledge of this subject to deeply question the study.”

He continues:

With both of these criticisms, Singal appears to think that the proper way to study the effects of puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones would be to compare the suicide rates in places based on the number of prescriptions being dispensed, the number of clinics offering these treatments, or their state reputation as being more or less permissive on transgender issues. While I understand why it is tempting to think that these direct comparisons would be better, if our goal is obtaining an unbiased, even if imprecise, estimate of causal effects, it is far better to focus on state minor access provisions. Because modern research designs for isolating causal effects are not necessarily intuitive, let me try to offer a brief explanation for readers (and Singal) who are not trained researchers.

Greene goes on at some length to explain why this would be a bad approach, but that’s irrelevant because I wouldn’t endorse it in the first place. I neither believe there are enough people on these treatments — nor that we should a priori expect blockers and hormones to have large enough effects on suicidality — that we should expect policy shifts pertaining to gender-affirming medicine to leave any fingerprint on local or national suicide stats at all. There aren’t a lot of trans people, fewer of them seek medical treatment, and fewer of them still seek it at a time when they are suicidal and we could therefore expect it to alleviate their suicidality. (Greene seems to be arguing that these treatments make people suicidal, but I’m very skeptical of any such straightforward connection. I think in cases where other, preexisting psychological problems contributed to suicidality and these weren’t addressed, you could have a situation where blockers or hormones don’t improve suicidality, but I’m aware of nothing in the scant research to offer much support for this idea of a causal link between access to gender-affirming medicine and increased suicidality. Or at least a consistent link, I should say — of course there could be outlying instances where, say, testosterone gives someone a boost of energy and impulsiveness that leads to a suicide attempt, or estrogen triggers some depression that does the same. All the more reason for careful screening and assessment.)

Further up in his follow-up article, Greene responds to claims made by the psychiatrist and frequent proponent of youth gender medicine, Jack Turban:

I never claim that “minors can easily access hormones without parental consent.” My study is based on the natural policy experiment that results from some states having one fewer barrier to minors getting these drugs by having a provision in law that allows minors to access healthcare without parental consent, at least under some circumstances. It just has to be easier for minors to get these drugs, not that they can do so “easily.”

But Turban seems to suggest on Twitter that this virtually never happens. Where would I get the idea that minors can access these drugs without parental consent? It comes from Turban’s own research. In his 2022 study on the effects of cross-sex hormones on suicidal ideation, he analyzes the results of a survey given to a convenience sample of adults who identify as transgender. In Table 1, he reports that 3.7% of those who say that they received cross-sex hormones between the ages of 14 and 17 are still not “out” to their families as transgender. These respondents must have obtained those drugs without parental consent since their parents do not even know that they identify as transgender. In addition, we see in that same table that only 79.4% of those adults who got hormones between the ages of 14 and 17 say that their families are supportive. We might reasonably assume that unsupportive families would not have given consent to their teenage children getting hormones, especially if they continue to be unsupportive several years later when those children are now adults. Yet somehow, nearly a fifth of those who got the drugs as teenagers did so despite the lack of support from their families.

Let’s just stop right there. Everyone knows that this is a thoroughly busted data set. See my last post on youth gender medicine for more details. But three-quarters of the kids who said they got blockers had their responses tossed out by the survey administrators because they said they did so over the age of 16, which is basically impossible, and there’s all sorts of other statistical weirdness in this sample, including a weird number of 18-year-olds. If we can’t trust this data to provide accurate information about who went on blockers, or even what age respondents were when they filled out the survey, there’s no reason to trust any of it to provide us with accurate data on more detailed questions.

In short, this data definitely cannot be used to assert that many kids obtained access to blockers and hormones without the knowledge of their parents. If Greene is making a “by Turban’s logic” argument, sure, whatever — at this point, anyone who has even briefly perused the U.S. Transgender Survey data knows it’s ridiculous how much Turban and other researchers are extrapolating from it. “Water from a stone” is an understatement.

But Greene’s own argument does rely on the idea that fairly large numbers of kids could access these treatments without parental consent. If for a sizable chunk of that 2010 to 2020 span there was very little of this going on in much of the country, then of course it’s bunk, definitionally, to point to changes in suicide trends and to not only attribute them, but attribute them entirely, to kids going on blockers and hormones.

One final point: Dave Hewitt, who goes by @void_if_removed on Twitter, posted his own critical response to Greene on Substack that has a lot of useful, more in-depth analysis.

Hewitt noted something strange about the sex ratios in Greene’s data:

Looking at the suicide data, another thing that leaps out is that the group most likely to commit suicide - and the group with the largest increase - are males aged 18-23. However the group with the largest increase in trans-identification is younger teenage girls. This again doesn’t add up. If the report is attempting to link suicide rates with juvenile transition, we would expect the demographic most likely to be affected to be most represented in the suicide stats, but the opposite is true. This lack of connection again points to the overall weakness of the report.

This is yet another solid reason to question Greene’s confidence that he can divine, from a small disjuncture in two groups of states’ youth suicide rates, that the causal agent is blockers and hormones.

There’s A Very Worrisome Trajectory Here

I think that overall, journalistic coverage of the youth gender medicine debate is improving. That’s in large part because the average normie recognizes the complexities and trade-offs here and wants to consume journalism that takes them into account.

But among partisan and hyperpartisan types, the landscape is getting crazier and crazier. It seems like left and right are locked in a bit of an epistemic death spiral, some sort of twisted race to produce the worst and most misguided arguments and data. Because liberals produce far more mainstream social science than conservatives, one way this has manifested itself has been through the publication of methodologically questionable studies, and then the enthusiastic, oversimplified promotion of said studies by media outlets and university PR offices. That’s why so many partisans on the left believe this is a settled issue and there’s no debate over blockers and hormones. And because conservatives control far more state governments than liberals, there’s been a misguided rush, in many red states, to ban youth gender medicine, and to attempt to commit grotesque injustices against those who furnish it, when these states could just as easily instead push for better clinical practices and data collection.

So the partisan landscape on this issue was already depressing as hell, but this Heritage report marks an unfortunate new low point, because there’s really a “hold my beer” aspect to it. Greene’s work doesn’t come anywhere close to supporting his extremely strong and alarming causal claims, and despite the evident weaknesses of this methodology it instantly went viral on the right. I can see why it’s a tempting means of triggering the libs — Oh, you were saying these treatments reduce suicidality… ? But it’s really bad that Heritage published this, and that so many conservatives are taking it seriously.

Questions? Comments? Examples of heartland states handing out copious quantities of puberty blockers and hormones in 2012? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The image of the front of The Heritage Foundation building is from here.

Good grief. That’s awful, awful reasoning. As someone who’s completely against puberty blocker treatment… thanks for keeping us honest.

Thanks for being one of the very few objective, good-faith actors in this shitshow of a debate.

It's extremely frustrating to see so much idiocy on both sides.