(If you’re reading this in your email client and have any issues due to its length, hop over to jessesingal.substack.com and read it there.)

Osita Nwanevu’s article in The New Republic, “The ‘Cancel Culture’ Con,” got a lot of attention when it went up on Monday. In it, he presents the vast majority of concerns over “cancel culture” as, well, a con — as misguided and opportunistic outrage directed against a world that is changing for the better. While I think “cancel culture” is an increasingly useless term — a point I’ll return to very shortly — I found Nwanevu’s article really, really off-base with regard to the broader controversy over online outrage and callout culture, and thought that it went out of its way to either completely avoid engaging with, or to mischaracterize, the arguments of those of us who have raised some level of concern over (ugh) “cancel culture.”

So for this post, which is going to be long, I’m going to go through Nwanevu’s article and unpack everything that I think is wrong with it or misleading about it. Then, in a concluding section, I’m going to comment more broadly on this style of work, bringing in a piece from earlier this year by another TNR staffer, Josephine Livingstone, that was much more directly about my own work than Nwanevu’s article, in which I’m just one of many media types mentioned.

(I should say that this entire post is probably pretty skippable if you’re not interested in the “cancel culture” debate, which I recognize that not all of my newsletter subscribers are. Also, if you have previously come across Livingstone’s piece and are interested in my critique of it, but not all this other stuff, you can search down to the phrase “I’ll wrap this up,” and you’ll find that that section mostly makes sense [or doesn't!] on its own.)

I think both articles are examples of what I am calling, for lack of a better phrase, “slalom punditry.” It’s a style in which certain pundits position themselves as tackling big issues in bold, fearless, truthtelling ways, cutting through all the bullshit out there, but in which they themselves are, in fact, the bullshitters. This particular subgenre of bullshitting involves whooshing past, slalom-style, any of the arguments or facts that could disrupt the author’s own certitude and moral righteousness without making any attempt to engage with them. It’s a superficially compelling but fundamentally bankrupt way of writing and thinking.

***

The problem that is giving rise to a lot of the messiness of the “cancel culture” conversation isn’t Nwanevu’s fault: As many people have pointed out, “cancel culture” doesn’t really have an agreed-upon definition. It’s one of those terms, like “political correctness,” that has become an overinflated political football. I’ve realized that it’s probably best not to use it at all, or to ask other people to specifically define what they’re talking about when they bring it up. If you see me ignore my own rule on this, please let me know.

But for the purposes of this post, I’m going to put the term in scare quotes and use it to point out different aspects of the broad discourse to which the phrase refers at different times. Because whatever “cancel culture” is, it’s a pretty big tent. A loud, roiling conversation about how technology has changed outrage and shaming dynamics has been going on for years now, ranging from the stories of random individuals getting caught up in unforgiving shame-vortices to essays arguing that social media (or generational change) is making everyone more sensitive than they used to be, and so on. (Lest I be accused of simply reframing this conversation so it occurs on more favorable terrain for my own arguments, Nwanevu himself acknowledges in his piece that “cancel culture” is more or less equivalent to “call-out culture” — we’re on the same page about that.)

So my main knock on Nwanevu’s piece is that he doesn’t really engage with any of the interesting “cancel culture” arguments. The vast majority of his piece simply points out, over and over, that various people purported to have been ‘cancelled’ are doing fine (more or less), which is a rebuttal to an argument few people are making.

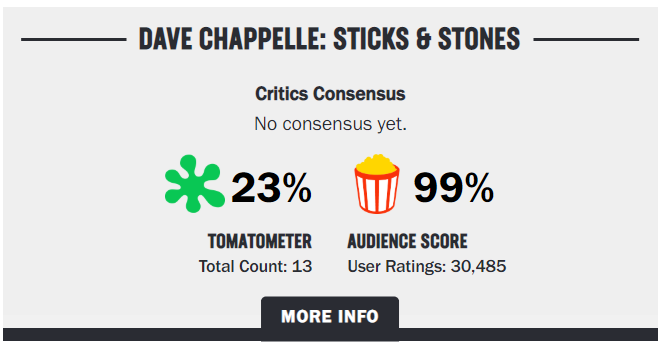

Early on, for example, Nwanevu focuses on the Dave Chappelle controversy, in which Chappelle has made offensive jokes about trans people and Michael Jackson’s victims, a bunch of people complained online, a bunch of people then complained about the complainers, and then… Chappelle suffered no real repercussions whatsoever and is still a comedy juggernaut who effortlessly rakes in tens of millions of dollars. It’s not that stories like this don’t have their own interesting bits to unpack — earlier this month I discussed the Chappelle situation in a way that I hope raised some worthwhile points about how elite, woke opinion on questions of “political correctness” or “cancel culture” or whatever the hell you want to call it is pretty far out of line with most Americans’. But to look at a situation like Chappelle’s and to focus mostly on the fact that he’s still doing quite well is to sort of miss the point, because there’s a lot more to discuss here. It’s only a tiny, tiny subset of the people discussing “cancel culture” whose most pressing concern is the fate of Dave Chappelle, anyway.

As for Nwanevu’s broader treatment of the comedy scene, he argues that the comedians complaining about “cancel culture” and political correctness are both the powerful titans who rule the industry, and that they are fading dinosaurs grasping at their last straws of relevance. This is the one part of his piece where, while I think Nwanevu gets things wrong, I can’t really accuse him of writing in a misleading or willfully myopic way (as I will do so enthusiastically later on). Here, I think there’s some genuine disagreement about how to interpret the available evidence, and it’s worth attempting to hash out.

He writes:

There’s a large audience for this kind of thing and comedy marketers are hip to it. A 2016 Joe Rogan special was titled, simply, Triggered. A new special from Bill Burr that offers subtle critiques of the turn against political correctness was nevertheless promoted by Netflix with a selection of clips from a rant in which Burr appears to mock the #MeToo movement, feminists, and the like. This year’s MTV Video Music Awards were hosted by 46-year-old comic Sebastian Maniscalco, whose opening monologue mocked millennials and teens. “If you feel triggered or you feel offended by anything I’m saying here or anything the musical artists are doing,” he said, “they’re providing a safe space backstage where you’ll get some stress balls and a blankie and also Lil Nas X brought his horse which will double as an emotional support animal.”

Those who turned to Google afterwards wondering how an aging comedian wound up on MTV sneering at young people the network has been struggling to reach might have happened across a Forbes article listing Maniscalco, who also released a Netflix special of his own this year, as one of the top ten highest paid comedians in the world in 2018, having earned an estimated $15 million. Chappelle was third, having earned $35 million. This “mutated McCarthy era” has treated the comics on that list particularly well, although some on it, beyond Chappelle, remain troubled by our cultural climate. Chris Rock (#4, $30 million) and Jerry Seinfeld (#1, $57.5 million), for instance, have been quoted in recent years, saying that over-sensitivity has made it impossible for comics to tour college campuses. In response, comedian John Mulaney argued that campuses have become sensitive not to the material of comics like Rock and Seinfeld, but to their astronomical performance fees.

…

[Shane] Gillis is now at the center of a discourse that suggests comedians should see, in critical tweets and Tumblr posts, the kind of threat comedians in Bruce’s day once saw in undercover policemen. This might be the funniest idea comics like Chappelle have left to offer us. As far as comedy is concerned, “cancel culture” seems to be the name mediocrities and legends on their way to mediocrity have given their own waning relevance. They’ve set about scolding us about scolds, whining about whiners, and complaining about complaints because they would rather cling to material that was never going to stay fresh and funny forever than adapt to changing audiences, a new set of critical concerns, and a culture that might soon leave them behind. In desperation, they’ve become the tiresome cowards they accuse their critics of being—and that comics like [Lenny] Bruce, who built the contemporary comedy world, never were.

There’s an important issue to resolve here. If Nwanevu is right that there is a broad base of support for criticisms like the ones leveled at Chappelle, and that comedians like him are failing to “adapt to changing audiences, a new set of critical concerns, and a culture that might soon leave them behind,” then it really could be the case that “CANCEL CULTURE!” is the dying wail of the soon-to-be fossilized comic. If, on the other hand, audiences aren’t changing that much after all, and there’s a lot of sympathy for Chappelle’s kvetching about “cancel culture,” then that’s a very different story, and one that is harder to square with the idea of a stubborn comedian clinging to increasingly obsolete material.

I think Nwanevu, like so many other progressive writers, fails to fully account for and grapple with the possibility that cultural elites are on a very different page than the population at large. It’s telling that later on in his piece he mentions younger critics of this sort of work specifically: “The critics of cancel culture are plainly threatened not by a new and uniquely powerful kind of public criticism but by a new set of critics: young progressives, including many minorities and women who, largely through social media, have obtained a seat at the table where matters of justice and etiquette are debated and are banging it loudly to make up for lost time.”

The part I bolded seems at least partially true, but I’m not sure Nwanevu is drawing the right lesson from it — I don’t think the drumbeat is one that the average liberal, whatever their color, is particularly interested in dancing to. As I pointed out in my Chappelle post and in this post about mostly white progressives speaking over marginalized people who are a bit more conservative than they are, there is evidence to suggest a pretty big gap between how the woker subset of progressives (the average writer criticizing Chappelle for a major progressive publication, or the average Twitter follower of such a writer) and the broader American left-of-center (the average Chappelle watcher or attendee of one of his shows, who isn’t online that much) view many cultural issues. Some of this is also captured in “The Great Awokening,” Matt Yglesias’s exploration of survey data showing, among other things, that “In the past five years, white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter.”

Comedy isn’t a particularly important example in the grand scheme of things, but it’s an instructive one. My view of the situation is this: If you are in that woker cohort, it appears to be blazingly obvious to you why, for example, it was okay for Chappelle to have spent years ridiculing crack addicts and using violence against sex workers and racial slurs as punchlines, and to have made fun of white heroin addicts in his latest special, but why it was not okay for him to have made fun of trans people and Michael Jackson’s victims (the latter in a gonzo, over-the-top bit in which, to my interpretation at least, Chappelle is clearly making fun of his own inability to honestly reckon with the musical legend’s very public disgracing). I couldn’t tell you why it’s blazingly obvious because I don’t quite understand the arguments, which are often premised on rather Talmudic readings of power relations that rarely make sense to me, but the point is there is broad agreement, among this cohort, that this is obviously true, and it appears that this cohort is overrepresented in journalism — as evidenced by all the think pieces from culture critics only now determining that Chappelle is problematic.

The argument of the wokest progressives is often not only that their view of what is and isn’t acceptable to joke about is obviously true, but also that anyone who disagrees with it likely wishes harm upon the groups being joked about. Nwanevu, for example, writes: “Netflix, unfazed by all the commotion, actively promoted some of the show’s controversial bits. It’s hardly surprising. Disbelief of sexual abuse and disgust for transgender people are mainstream enough that Chappelle could take on a second career as a Republican speechwriter.” This comes across as an intentional act of self-stupidification on Nwanevu’s part. There’s just no conceivable way he actually believes that if someone laughs at a joke about X, they harbor ill will toward X. I am positive Nwanevu has laughed at offensive jokes, but that he did so for the complicated human reasons most of us do. I think “The Producers” is hilarious. Does that mean I don’t take the Holocaust seriously? Do the many people who laughed at Tyrone Biggums over the years literally hate crack addicts and want to see them humiliated? This isn’t even close to a psychologically serious understanding of what humor is, but it usefully illustrates the way moral judgement has been injected into line-drawing questions about humor that lack easy answers.

But again, this is part of a broader lack of interest, on the part of the cultural critics mad that people are mad that people are mad at Chappelle (and others), in the question of how much popular support there is for the outrage his latest work kicked up online. Rather than grapple with the thornier questions of what’s acceptable and why and who decides and on the basis of what authority and logic they do so, it’s simply taken as obviously true that the standards adopted by Chappelle’s critics are correct, and that disagreement with those standards indicates immorality and a lack of concern for vulnerable people.

Nwanevu doesn’t, and can’t, marshall any real evidence for his theory that problematic comedians risk pissing off some emerging plurality or majority of young fans (as opposed to professional critics) uninterested in, and offended by, Chappelle’s most controversial material — that these comedians are threatened by “changing audiences, a new set of critical concerns, and a culture that might soon leave them behind.” In fact, all the limited evidence we have suggests otherwise, that there is not going to stop being a market for such material anytime soon. Seventy-nine percent of Americans 24 and under, when asked whether political correctness is a problem, answer that it is — just a single percentage point below the overall national figure of 80%. Is this a perfectly worded or crystal-clearly defined question? No. But obviously the sort of person who thinks Chappelle crossed a line is not going to respond ‘yes’ to such a question, and 80% is 80%: It’s a lot. While members of that remaining 20% are massively overrepresented on the masthead of The New Republic and similar publications, overall, they are a minority at the national level.

So Nwanevu’s claim that the comedians he cites are soon to be on the wrong side of history is totally unsupported and, I would argue, wishful thinking. It also ignores the fact that we have had these debates over and over and over, that one generation replaces another replaces another and we are always arguing over political correctness, comedians are always pushing boundaries, there are always complicated conversations going on about where various lines should be drawn, and so forth.

I don’t want to take this claim too far or ignore the kernel of truth in Nwanevu’s article. Yes, standards and audience taste do change over time. Jokes about pushy wives that would have been standard sitcom-fodder 15 years ago likely would elicit more groans today, and might eventually go extinct when it comes to mainstream media outlets like the major networks. But I think this process is slow and unpredictable, and there will always be a healthy market for transgressive comedy. So the claim I’m making is a lot narrower than the claim that suddenly Chappelle’s material is too offensive, or is on the verge of being too offensive, for a big and important subset of standup-comedy consumers.

So until we have any evidence to suggest otherwise, imagine if — bear with me, and sit down if you’re easily startled — young Americans are broadly liberal, are in favor of LGBT rights, abhor racism and other forms of bigotry, are increasingly in favor of a vibrantly multicultural approach to everything, but also think that it’s okay to make offensive jokes, because jokes are jokes and don’t, in most instances, do any harm..

I know, I know… it’s a bizarre idea. Especially if you are heavily invested in the culture wars and don’t get out of your bubble much.

***

In the next section, Nwanevu continues his annoying habit of pretending that, in 2019, the phrase “cancel culture” is always intended to refer to people whose lives or careers have been ruined, and that he is making some sort of important observation by pointing out that sometimes, ‘cancelled’ people aren’t actually cancelled(!):

Perhaps this is too flippant a dismissal. “Cancel culture,” after all, is a phrase deployed widely outside the world of comedy to describe an all consuming, social media-fueled climate of outrage—a dark cloud hanging over not only comics, but also a wide range of public figures and entities, some of whom where helpfully named by a New York Times piece last year, “Everyone is Canceled”:

Bill Gates is canceled. Gwen Stefani and Erykah Badu are canceled. Despite his relatively strong play in the World Cup, Cristiano Ronaldo has been canceled. Taylor Swift is canceled and Common is canceled and, Wednesday, Antoni Porowski, a Queer Eye fan favorite was also canceled. Needless to say, Kanye West is canceled, too.

Significantly, all of these figures are alive, well, and prosperous today—as are the people, brands, and projects named in a Wired piece about the Chappelle controversy earlier this month[.]

‘Significantly’? Why is it significant? If you actually read the New York Times piece, by Jonah Engel Bromwich, you’ll see that one of the subheds asks “Is Anyone Ever Really Canceled?,” and a few sentences later Bromwich writes that “an act of cancellation is still mostly conceptual or socially performative.” Bromwich, like every other writer covering this issue in an interesting way, understands that ‘cancelled’ doesn’t always literally mean ‘cancelled’ — his piece approaches the “cancel culture” controversy through the lens of various aspects of modern capitalism and the (fleeting) sense of power and agency social media can confer upon cancellers. Whatever one thinks of his arguments, Bromwich actually shines a light on some potentially interesting aspects of “cancel culture.” Then Nwanevu reads this piece — again, a piece which explicitly states that being ‘cancelled’ doesn’t mean you necessarily lose much of value — and chimes in to point out that “all of these figures are alive, well, and prosperous today[.]” Okay!

Weirdly, he keeps doing this — his next excerpt of a list of supposedly cancelled figures comes from a Wired article whose author writes “People who are canceled usually don’t stay that way, and often the attention just fuels their success. Many of the canceled people whom The New York Times name-checked last year are no longer canceled—Taylor Swift, Queer Eye’s Antoni Porowski, and Chris Evans seem to be doing fine.” He then excerpts another list of the supposedly cancelled from a Digiday article which notes, in part, that “It’s unclear if canceling something means actually canceling it. Equinox, after all, remains in business. Other figures who have been canceled, from Taylor Swift to YouTuber Logan Paul, are also still thriving.”

Summing up all these articles, Nwanevu writes:

If we take these lists seriously, cancel culture, as best as one can tell, seems to describe the phenomenon of being criticized by multiple people—often but not exclusively on the internet. Neither the number of critics, the severity of the criticism, nor the extent of the actual fallout from it seem particularly important. A great many people find Louis CK to be disgusting. The same can’t yet be said for guacamole. Both, we’re told urgently, have been canceled.

But every single article he links to and quotes from acknowledges that there are various gradations of ‘cancellation’ and rejects the simple idea that the word ‘cancellation’ and its variants always mean having one’s career or life permanently disrupted. Who is being argued with here? When Nwanevu says “we’re told urgently,” who is doing this telling? Who is comparing guacamole to Louis CK? This all feels like the equivalent of me telling a friend, “You know, I heard you say you hate onions, and I also heard you say you hate Hitler — you’d really put onions on the same plane as Hitler?” My friend would roll his eyes, and justifiably so.

Next comes probably the meatiest part of his article, where Nwanevu highlights some hyperbolic claims about cancel culture he has encountered recently:

Since their piece on “cancel culture” last year, writers at the Times alone have referenced the concept in at least 14 articles on subjects ranging from Joe Biden’s age to a revival of Kiss Me, Kate on Broadway. This count doesn’t include references to “call-out culture,” a close synonym invoked by David Brooks earlier this year in a column about a woman “cancelled” or “called out” online after it was discovered she had engaged in cyberbullying during high school. Her saga, featured in the podcast Invisibilia, troubled Brooks deeply. “I’m older, so all sorts of historical alarm bells were going off,” he wrote. “The way students denounced and effectively murdered their elders for incorrect thought during Mao’s Cultural Revolution and in Stalin’s Russia.” Later in the column, he described call-outs as “a step towards the Rwandan genocide.”

Statements like this are routine in cancel culture discourse—any particular cancellation, no matter how trivial or narrow it may seem to the casual observer, evidently carries within it the seeds of something much more grave. In a March column, TheWall Street Journal’s Peggy Noonan also made reference to torture and indoctrination under Mao. “I don’t want to be overdramatic, but the spirit of the struggle session has returned,” she declared. “Social media is full of swarming political and ideological mobs. In an interesting departure from democratic tradition, they don’t try to win the other side over. They only condemn and attempt to silence. The spirit of the struggle session is all over Twitter.”

Being cancelled on Twitter, then, is an event that belongs to an alarming lineage of severe intolerance, cruel persecution, official condemnation, and vindictive upheavals. The list of weighty precedents is endless. Nelson Mandela was cancelled. Martin Luther King Jr. was cancelled. The Beatles were cancelled. Lenny Bruce, of course, was cancelled. Vladimir Nabokov, D.H. Lawrence, and James Joyce were all cancelled. Alfred Dreyfus was cancelled and, famously, uncancelled. Robespierre, like fellow canceller par excellence Joseph McCarthy, eventually got himself cancelled. Twenty unlucky Puritans were cancelled at Salem. Galileo was cancelled. Martin Luther was cancelled. Joan of Arc was cancelled. At least half a dozen popes have been cancelled. Jesus was cancelled. Socrates was cancelled. The pharaoh Akhenaten, reviled and stricken from official records for introducing monotheism to Egypt, was cancelled quite thoroughly in the fourteenth century BC. In the twenty-fourth, Lugalzagesi, uniter of Sumer, was cancelled by Sargon of Akkad and a cheering public as he was marched in a neck stock through the city of his coronation and executed. Et cetera.

I’m not sure where to begin. It’s good, at least, that Nwanevu notes that “call-out culture” is a “close synonym” to “cancel culture,” because it nicely highlights everything he is willfully ignoring. If we focus in on the “call-out culture” aspect of this conversation, which we can define simply as the tendency to aggressively critique and shame those who say offensive things online, there are a lot of genuinely disturbing incidents Nwanevu could have mentioned but elected instead to ignore, lest they untidy his narrative.

In 2015, for example, I reported on the story of Monica Foy, a college student whose offensive joke about a dead sheriff’s deputy, made on a Twitter account with almost zero followers, was discovered and blown up by Breitbart. She then had to flee her home amidst a torrent of death and rape threats. Everyone knows about the similar, but even worse, stuff that happened to Zoe Quinn during GamerGate. And Justine Sacco’s travails. Or there’s the Cecil the Lion controversy, which, if you listen to this excellent RadioLab, you might find to be more controversial than you believed. Then there’s the story of Vic Berger IV, who dealt with a wave of online accusations he was a pedophile, on the basis of zero evidence, after the unhinged and pedophile-obsessed far-right figure Mike Cernovich targeted him over a very low-stakes online beef they were engaged in. (I understand that some people have chosen to define “call-out culture” as solely a left-wing phenomenon, but I reject that entirely given the similarity between left-wing and right-wing behavior on this front, and given how frequently right-wingers engage in it. It makes no sense to define “call-out culture” or “cancel culture” or “political correctness” or any such term as being the sole or primary province of the left or right, given the voluminous evidence we have suggesting that these phenomena all stem from deep-seated human tendencies, not the particulars of one political camp or another.)

Foy’s scary story isn’t the only example of how questionable media behavior can exacerbate these situations and cause harm. Last year, a woman in Portland was widely portrayed as racist for — the story went — calling the cops on a black guy whose parked car was blocking a crosswalk. The tabloidish headlines helped turn the outrage meter to 11: “‘CROSSWALK CATHY’: WHITE WOMAN ALLEGEDLY CALLS COPS ON BLACK COUPLE FOR PARKING JOB” (Newsweek); “‘Crosswalk Cathy:’ Woman calls the Bureau of Transportation on couple for bad parking job” (Yahoo); “#CrosswalkCathy Calls Police on Black Man Because She Didn’t Like The Way He Parked” (The Root). Except, if one believes in the laws of time and space, it’s impossible she was motivated by race, because she reported the car (to a non-police hotline) before knowing who the driver was. Didn’t matter: Online outrage has its own sets of laws and rules, and a bunch of idiot internet vigilantes quickly went to work doxxing “Crosswalk Cathy” and attempting to make her life a living hell. Remarkably, many of the articles with loud, racism-accusing headlines related the timeline of the incident accurately in their actual bodies — meaning writers or editors or web producers must have known exactly what they were doing in playing up a clickbaity, outrage-fomenting, chronologically impossible race angle. Even more remarkably, many of these outlets still haven’t corrected the false claim that “Crosswalk Cathy” called the cops rather than a non-police number, which matters a lot in this context. This all feels like a pretty good example of “cancel culture”!

At Yale, there was a somewhat similar controversy earlier in 2018: A grad student called campus police on a black woman sleeping in a student lounge. A bunch of news outlets and Yale activists and a furious band of Twitter users, outraged at this seemingly bigoted act, responded in a way that can only be interpreted as an attempt to destroy the grad student in question. Except that story, too, was a lot more complicated than it initially appeared. It’s a long one, well-told by Cathy Young, involving trauma and mental illness and all sorts of strife and misunderstanding, but it’s just impossible — I mean that — to learn the details and remain confident this was, at root, about race rather than a host of other stuff. (Which is not to say, of course, that other, similar situations aren’t about race; of course people get harassed because of their race, all the time.)

As a final example of how brutal these outrage campaigns can get, there’s the case of the Steven Universe fan artist who was bullied to the point of a suicide attempt for drawing cartoon characters too fat or too skinny or the wrong color or whatever else. Once the online mob decided she had sinned against the show, and against social justice (conveniently, there’s always a super-important principle at stake to justify sociopathic online behavior), no punishment was too harsh. It’s a very hard story to read, but I hope people click that link.

In all these cases, whatever the controversy or the politics, the people who get sucked into these shame-vortices stand a pretty big chance of their life being changed forever, often in ways that the average person would find grossly unfair and disproportionate. They go through what is often a genuinely horrifying, traumatic experience. And if you have a trace of curiosity, it’s impossible not to be fascinated by this, or to be compelled by the most thoughtful accounts of the phenomenon, like Jon Ronson’s. Mobs aren’t new and outrage isn’t new, but what is new is the way a non-public figure can be captured forever at their worst or most misunderstood moment, and have that define them forever. Technology has permanently amplified one of the uglier and more primal and difficult-to-wrangle parts of human nature.

Since Nwanevu acknowledges that “cancel culture” and “call-out culture” are closely related, it might be interesting to hear what he thinks of these stories. Did the victims deserve it? Did the outlets in question act responsibly? Should we be trying to nudge certain norms in certain directions to account for the sheer speed with which outrage can spin virally out of control these days? Do social-media platforms themselves have a role to play in mitigating this sort collateral damage, given that they benefit directly from the emotionally charged content that causes it?

We never find out, because rather than engage with actual examples of the phenomenon he is writing about that are difficult to wave away as irrelevant, Nwanevu cherrypicks the phenomenon’s tiny handful of least-harmed and most powerful ‘victims’ and the “cancel culture” discourse’s most over-the-top quotes from conservatives. Struggle sessions! Ha-ha. How silly. Nothing to see here. How could something David Brooks hyperventilated about once possibly deserve any serious analysis?

Nwanevu continues:

Yet it seems at least possible that tweets are just tweets—that as difficult as criticism in the social media age may be to contend with at times, it bears no meaningful resemblance to genocides, excommunications, executions, assassinations, political imprisonments, and official bans past. Perhaps we should choose instead to understand cancel culture as something much more mundane: ordinary public disfavor voiced by ordinary people across new platforms.

Imagine if — and please indulge me as I wander off into another completely wild hypothetical — it were at least possible to conceive of a way of writing and thinking about technologically mediated and amplified forms of outrage and shaming that landed, say, somewhere between “No reasonable person should be genuinely worried by or interested in any of this” and “Mean tweets are literally the Holocaust.” If only!

I also don’t want to let “ordinary public disfavor voiced by ordinary people across new platforms” sneak by unnoticed. If there’s one thing everyone knows about social media by now, it’s that its users are very far from a representative slice of the broader population. The evidence suggests that “Twitter Is Not America,” for example, with recent Pew research showing that, as Alexis Madrigal summed it up in The Atlantic, “Twitter users are statistically younger, wealthier, and more politically liberal than the general population. They are also substantially better educated, according to Pew[.]” But you can apply this general logic however feels appropriate to any given internet controversy: The people who hounded Monica Foy from her home weren’t a random slice of normal Americans, either, but rather Breitbart readers and others looped in with right-wing online social networks.

Which opens up another potentially interesting conversation that Nwanevu slaloms right past: Different controversies attract different audiences, and as communication entails less and less friction and effort — I can type “Fuck you” to another real-life human being faster than I can grab a glass of water from my kitchen — that makes it increasingly important for decision makers to understand which forms of feedack they should heed, and which forms they should ignore, because there will always be jerks on Twitter (or wherever) mad about everything. That’s why I mostly stand by my argument from 2017 that “Companies Should Ignore Angry Online Mobs More.” Whether or not you agree with me, surely this is a practically important, rich vein of the “cancel culture” conversation that deserves some thoughtful mining. But there’s none to be found in Nwanevu’s article — after all, online outrage is just “ordinary public disfavor voiced by ordinary people across new platforms.”

***

Nwanevu then proceeds to his critique of how a number of journalists, including me, have covered the social-justice dumpster fires that have been raging in the online world of young-adult fiction for the last couple years or so. If you’re not familiar with this stuff, Kat Rosenfield’s piece in Vulture is the place to start. There’s also my piece in Tablet, or the series of emails I posted from those in YA who are concerned about what’s going on which starts here (I received dozens, but in a certain sense the most important ones came from writers of color who feel pressured, by mostly white editors ostensibly deeeeeeeeeply concerned with social justice, to write about their identities in a very particular way that feels uncomfortable or irrelevant or exploitative to them).

It will not surprise you that Nwanevu believes there is nothing to see here. I’m going to jump around order-wise a bit, and start with what I view as a pretty dishonest distortion of what Rosenfield wrote in her Vulture article:

The [Kosoko] Jackson and [Amélie] Zhao controversies came roughly a year and a half after “The Toxic Drama of YA Twitter,” a piece by New York magazine’s Kat Rosenfield about Laurie Forest’s The Black Witch—another fantasy criticized online for its handling of race—and the YA book world’s other supposed casualties of cancel culture, which Rosenfield listed:

In recent months, the community was bubbling with a dozen different controversies of varying reach — over Nicola Yoon’s Everything Everything (for ableism), Stephanie Elliot’s Sad Perfect (for being potentially triggering to ED survivors), A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas (for heterocentrism), The Traitor’s Kiss by Erin Beaty (for misusing the story of Mulan), and All the Crooked Saints by Maggie Stiefvater.

Elsewhere in the piece, she named two other condemned titles: E.E. Charlton-Trujillo’s When We Was Fierce, criticized for stereotyping African-Americans, and Keira Drake’s The Continent, yet another racially problematic fantasy.

For all the online ruckus Rosenfield chronicles in the piece, it seems significant every title referenced within it but one, including The Black Witch, has been published. Everything Everything, in fact, was a Times bestseller and adapted into a feature film. The author of the lone exception, Charlton-Trujillo, released her third YA novel this year.

But Rosenfield simply was not listing what she viewed as “casualties of cancel culture.” Here’s that full section of her article:

And even if it becomes an article of faith that certain books are harmful and shouldn’t exist, how to adjudicate the claims of harm is a question nobody seems able to answer. During our conversation, the ambivalent agent suggests that Twitter shaming is called for “when someone is resistant and won’t acknowledge when they’ve clearly made a mistake,” but hedges on the question of who gets to decide what a clear mistake looks like, or when an authorial decision is a shaming-worthy offense:

“I don’t have an easy answer to that. The problem with these sorts of conversations and debates online is that as soon as an accusation is made, the burden of proof is put on the accused party. You can make all sorts of allusions to The Crucible. I don’t know what needs to be done. I’m certainly not happy with how it plays out.

“But,” he adds, “I don’t think the answer is to have everyone shut up and not criticize it.”Twitter being Twitter, that outcome seems unlikely. In recent months, the community was bubbling with a dozen different controversies of varying reach — over Nicola Yoon’s Everything Everything (for ableism), Stephanie Elliot’s Sad Perfect (for being potentially triggering to ED survivors), A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas (for heterocentrism), The Traitor’s Kiss by Erin Beaty (for misusing the story of Mulan), and All the Crooked Saints by Maggie Stiefvater (in a peculiar example of publishing pre-crime, people had decided that Stiefvater’s book was racist before she’d even finished the manuscript.)

But in an interesting twist, the teens who make up the community’s core audience are getting fed up with the constant, largely adult-driven dramas that currently dominate YA. Some have taken to discussing books via backchannels or on teen-exclusive hashtags — or defecting to other platforms, like YouTube or Instagram, which aren’t so given over to mob dynamics. But others are pushing back: Sierra Elmore, a college student and book blogger, expressed her frustration in a tweet thread in January, writing, “[Being] in this community feels like being in high school again. So much. No difference of opinion allowed, people reigning, etc… I and other people I know (mostly teens) are terrified about speaking up in this community. You don’t get a chance to be wrong here.”

Rosenfield is specifically saying that many readers are tired of these controversies and unmoved by them, and describes the controversies as being “of various reach.” How does Nwanevu infer from that that Rosenfield believes the listed names to be “casualties of cancel culture” — the word ‘cancel’ and its variants, by the way, appearing nowhere in Rosenfield’s piece?

Nwanevu is trying to massage the facts to promote a narrative in which Rosenfield, as part of some sort of unhinged and uninformed rant about cancel culture, is pointing to a bunch of authors who are doing fine and is declaring them to have been grievously, permanently harmed because of the online mob. Which would be dumb! But Rosenfield isn’t dumb — she’s smart. She wrote a thorough, carefully reported piece that both covers the excesses of what’s going on in YA fiction and explains that there are very real issues with diversity and representation and access to the industry fueling the online pileons. In that piece, she is rather specific on the question of who is harmed, and how much: “Even The Black Witch, which took one of the worst online beatings in recent memory, scored a No. 1 rating in Amazon’s department of ‘Teen & Young Adult Wizards Fantasy’ a few days after its release and has been overwhelmingly well-reviewed since,’ she writes at one point. Nwanevu simply ignores all of this.

Let’s review this sequence: Kat Rosenfield writes in an article that despite all the controversy surrounding the young-adult novel The Black Witch, it did well, and Osita Nwanevu then criticizes that article on the grounds that… The Black Witch was published after all. It almost feels like he was making a concerted, conscious effort to miss the point of Rosenfield’s article.

I think the fundamental problem, other than that Nwanevu doesn’t seem all that interested in carefully reading the stuff he critiques — more on which soon — is that he thinks there is some very clearly defined battlefield here, with one side that is worried about cancel culture, one side that is not worried about cancel culture, and no middle ground or nuance worth exploring. It is very important to him to broadcast, as loudly as possible, that he is standing on the correct side of this battlefield, and to portray all those people on the other side as being united in opposition to him and his fellow reasonable pundits who just want people to stop freaking out about this “cancel culture” myth.

I got a sense of this when, against my better judgement, I asked him about some of this stuff on Twitter, and this was one of his replies:

Of course, I have never defined “cancel culture” in that manner anywhere, and have written about multiple instances of right-wing outrage ruining or at the very least complicating people’s lives. I also don’t know what Nwanevu means by my ‘ilk’ — it is a lonely feeling to lack knowledge of one’s own ilk! But this helps explain why he has so much trouble processing Rosenfield’s actual views, or relating her work fairly — he is trying to lump her in with a big enemy camp supposedly all expressing the same dumb, reactionary opinions on this subject. Rosenfield is more useful, to Nwanevu, as a hysterical mascot of the enemy ‘side’ than as a writer who has done real reporting on this issue and whose work could have possibly made some points worth genuinely reflecting upon and engaging with.

As am I! Here’s how he covers my own work on YA social-media drama:

The controversy surrounding that book, Blood Heir by Amélie Wen Zhao, was covered in a Tablet article titled “How a Twitter Mob Derailed an Immigrant Female’s Budding Career,” by Jesse Singal—part of his ongoing effort, he wrote, to catalog “pathological social rituals in online communities.” Singal wrote that he’d been tipped off to a “whisper campaign” against Zhao, which mostly amounted to posts arguing her novel, a fantasy about a magical society defined by a caste system in which, according to PR copy, “oppression is blind to skin color, and good and evil exist in shades of gray,” trivialized racism and American slavery.

This is a complete misreading of my “whisper campaign” reference, which was not about the social-justice critiques. Sorry for another long excerpt, but I want to make it clear just how much stuff Nwanevu failed to read carefully or intentionally misrepresented.

Here’s what I wrote:

Further heightening the drama [on YA Twitter], these pile-ons are often accompanied by claims that those who have been selected for dragging or excommunication have not only sinned against social justice, but pose a safety threat to others in the community. To be sure, online harassment can be a genuinely scary experience when it occurs. But within YA Twitter, harassment accusations are almost a tic at this point, and many of them don’t pass the smell test. Rosenfield, for example, asked the author of the anti-The-Black-Witch post for an interview, was politely turned down, and then watched as she “announced on Twitter that our interaction had ‘scared’ her, leading to backlash from community members who insisted that the as-yet-unwritten story would endanger her life.”

Between Rosenfield’s article and my general fascination with pathological social rituals in online communities, I had long kept one eye on YA Twitter. Last week, I was tipped off that there seemed to be some sort of drama brewing there—someone or some group had started a whisper campaign against this Zhao person. A YA reviewer with just 800 or so Twitter followers appears to have been the first to make these accusations public. She said: “I have nothing to lose by it and have the time, I’ll tell you which 2019 debut author, according to the whisper network, has been gathering screenshots of people who don’t/didn’t like her book. Amelie Wen Zhao.” As justification for airing whisper-network rumors, the woman tweeting suggested that Zhao’s alleged wanton screencapping constituted an actual threat of some kind: “Readers should be aware of this for their own protection. That’s why I’m saying it publicly after some confidential sources let me know privately.” The tweeter, who is white, explained to a skeptical replier that “I’m not ruining her life. I’m making public with permission what POC told me privately so in order to protect reviewers.” (If a confused friend ever asks you to sum up the culture of YA Twitter in one sentence, “Imagine a white woman explaining that she is spreading unverifiable rumors about a first-time author of color in order to protect people of color” will do nicely.)

I’d argue this actually warrants a correction of Nwanevu’s article. My entire paragraph on the “whisper campaign” is about the bizarre, borderline-nonsensical rumor-mongering that engulfed Zhao before the racism claims first popped up. The racism claims were not a whisper campaign — they were right out in the open! Part of the work these paragraphs did in my story was to point out what an intense hothouse of an online environment YA Twitter is, and how easy it is to be accused not only of having politically problematic opinions, but of actively plotting to harm your fellow writers or editors or critics. On YA Twitter and the other social-media communities that circle it, unproven accusations of ‘abuse’ and ‘harassment’ are constantly weaponized and disseminated without evidence. That’s part of the reason I’ve heard from many people in this world who won’t even make milquetoast critiques under their real names because of how scared they are of the insanity that can so easily engulf anyone viewed as stepping out of line.

But of course Nwanevu’s readers don’t get any of that — instead, he leaves out the material in both my story and Rosenfield’s which most clearly shows how off-the-rails this online community can get, and the intensity of the social and professional repercussions faced by YA’s perceived wrongdoers. Again: This allows him to ignore the reality of the story, and to avoid engaging with any of the tricky bits that might make it difficult for him to make sweeping claims about who is right and who is wrong. There’s no time for nuance when the culture-war bullets are flying.

Moving on:

Singal, citing an apology from Zhao in which she said that the book had been an allegory for contemporary slavery, concluded his piece with a solemn shake of his head. “[T]he book, which was intended as a comment on contemporary slavery in a part of the world most Americans know nothing about, probably won’t be published,” he wrote, “and won’t give American readers a chance to read the perspective of an Asian writer inspired by an issue of urgent importance to many Asian people.”

[...]

As for Jackson and Zhao, the decision to suspend their debuts was entirely voluntary and entirely their own, as The New Yorker’s Katy Waldman wrote earlier this year. In his tweeted apology to critics, Jackson conceded that he had “failed to fully understand the people and the conflict” central to his novel. In hers, Zhao expressed gratitude to those who had spoken up about the book’s themes. “I have the utmost respect for your voices, and I am listening.” This was received well by those who had led critiques of Blood Heir. “When Zhao apologized and withdrew her book, Y.A. stakeholders largely greeted her words with support and encouragement,” Waldman wrote, “seeing them as the result of being ‘called in’—reminded of one’s values as a community member—rather than ‘called out.’”

Kosoko Jackson now has another novel set for release in the spring. Zhao’s Blood Heir—the novel that inspired Soave’s allusion to book burnings, the novel Singal suggested would never be released thanks to a controversy that “derailed” Zhao’s career—will be out in November.

Ah yes, that entirely voluntary decision both authors made after watching influential subsets of their professional networks turn against them overnight, spread rumors about them, and read various out-of-context bits of their work in as uncharitable a light as possible. Every step of the way Nwanevu is excising context from his retelling, and in this case the missing context helps reveal just how sociopathic these blowups can get, and how damaging they can be to their victims. To take one example from Jackson’s case: A very popular and influential YA author, Heidi Heilig, who is at the center of many of these campaigns (partly through her tweets, partly through a closed Facebook group she runs and has publicly mentioned multiple times through which the outrage campaigns are sometimes organized and focused), positively blurbed Jackson’s book and then helped lead the charge against him. Can you imagine the feeling of having an important professional ally positively blurb your book and then turn against it at the first whiff of controversy?

But don’t worry: Jackson and Zhao did what they did voluntarily. Not long after laughing off Peggy Noonan’s claim that “I don’t want to be overdramatic, but the spirit of the struggle session has returned,” Nwanevu wants you to know that there’s nothing to worry about here, because the ‘victims’ actually thanked the critics who feverishly and dramatically denounced them online. For what it’s worth, I wasn’t the only person to notice how strange it was to stress the supposedly voluntary nature of these unpublishings and thank-yous:

There’s a lot to be annoyed by in Nwanevu’s piece, but, in an egocentric way, this sentence sits near the top of my list: “Zhao’s Blood Heir—the novel that inspired Soave’s allusion to book burnings, the novel Singal suggested would never be released thanks to a controversy that “derailed” Zhao’s career—will be out in November.” For one thing, ‘derailed’ appears in the headline of my piece, not the piece itself — and certainly seemed appropriate at the time, in the wake of the unpublication of a much-celebrated debut!

But more importantly, Nwanevu is simply up to his same tricks here, ignoring the actual context of what I wrote in favor of zooming in on the question of literal cancellation. I specifically pointed out in my piece that there was a chance Blood Heir would still come out, and specifically explained why, if it did, this whole episode would remain quite worrisome:

In a certain visceral sense, it doesn’t feel like Zhao’s trilogy could really be gone—it just doesn’t make sense that this was all it took. And maybe, as some online are already hinting, she will revise the book to make it more acceptable to YA Twitter—perhaps she can replace all that pesky material darkly inspired by modern-day human trafficking with references American Twitter critics find easier to process. Either way, this was a big deal. Surely other publishers will take notice and make decisions accordingly the next time a manuscript with anything bearing even passing resemblance to hot-button issues crosses their desk, even if it’s written by an author of color.

I am not the only person who has made this point — Rosenfield did, too, and Nwanevu himself quotes Jennifer Senior’s concerns in the New York Times that if this trend continues, “we’ll soon enter a dreary monoculture that admits no book unless it has been prejudged and meets the standards of the censors.” If you agree this is a concern, then of course the fact that Zhao’s book will eventually get published isn’t much consolation. The campaign against Blood Heir relied on so much misunderstanding (assuming a character was intended to be coded as black who wasn’t), so much genuine malfeasance (spreading unverified rumors about Zhao’s online conduct), and such Americocentric historical ignorance (assuming that any fictional reference to slavery must be an allusion to American slavery), that the obvious question is whether we should want such critiques to influence publishers and authors in general. Nwanevu, who is himself a professional writer who could, in theory, find himself negatively affected by these forces, doesn’t find any of this potentially concerning? There’s nothing to talk about here? Come on.

More broadly, I’m just struck by the bad-faith nature of the critique. Whatever you think of my argument or politics, I hope you can understand how a sequence like this is frustrating to a writer:

Me: This book got unpublished. It might still see the light of day, but even if it does that won’t address the reasons we should find even its temporary unpublishing disturbing.

Osita Nwanevu: Jesse Singal said the book wouldn’t get published but now it’s going to get published!

Not great.

***

The worst worst part of Nwanevu’s article — where it tips over from point-missing and context-stripping to, in my opinion, being outright disgraceful — comes at the very end, and it reads as follows:

This isn’t to say, of course, that there aren’t real instances of intolerance and repression around for our putative chroniclers of cultural ostracism to take an interest in. In April, a 23-year-old Dallas woman named Muhlaysia Booker backed into a car in an apartment parking lot. The driver of the other car then held her at gunpoint to force her to pay damages. As the confrontation took place, a bystander was offered $200 to attack Booker. He obliged. In a video that subsequently went viral, a mob—a real one—can be seen joining in, punching and kicking her in the head and yelling slurs as she squirms and struggles on the ground. She was hospitalized with a concussion and facial fractures.

Muhlaysia Booker isn’t going to be given a column in which she might describe her treatment to the public. She won’t be appearing on any panels or podcasts. She won’t be doing any standup sets. Muhlaysia Booker is dead. A month after the attack, her body was found face down in an East Dallas street with a gunshot wound. She was one of nineteen transgender people to have been murdered so far this year in a wave of violence the American Medical Association has called an epidemic.

The cultural power the critics of cancel culture breezily ascribe to progressive identity politics did not save them. It hasn’t yet afforded their deaths the pride of place in our discourse which our media class—in its incredible, bottomless narcissism—readily gives to elite university dramas and the insults that land in their Twitter notifications. The power to cancel is nothing compared to the power to establish what is and is not a cultural crisis. And that power remains with opinion leaders who are, at this point, skilled hands at distending their own cultural anxieties into panics that—time and time and time again—smother history, fact, and common sense into irrelevance. Cancel culture is only their latest phantom. And it’s a joke.

It’s clear that Nwanevu wanted to employ the horrific murder of this trans woman to help him win his argument about cancel culture, but he doesn’t even bother to summon a reasonably credible justification for bringing it up. I guess the closest he gets is the line “The cultural power the critics of cancel culture breezily ascribe to progressive identity politics did not save them.” What does that mean? Who is the person, anywhere, who is claiming that because “cancel culture” exists and in some cases leads to certain regrettable excesses, this shields powerless people from horrific forms of victimization? This isn’t a straw man — it is smaller strawman perched on the shoulder of a bigger one, flipping a contemptuous middle finger at readers. Having spent thousands of words trying to land as many blows as possible in this culture-war skirmish using every cheap rhetorical trick at his disposal, Nwanevu concludes his article with a grotesque flourish: “And if you don’t believe me, check out this dead trans woman.”

Again, disgraceful is the only word for this.

***

I’ll wrap this up soon, I swear. But whenever I engage in the masochistic act of a deep dive into a piece like Nwanevu’s, I like to try to pull out some threads that might show up in other pieces of its, well, ilk. I do think it’s useful, faced with a piece like this, to not only explain “Here’s why X is wrong, here’s why Y is wrong, and here’s why Z is wrong,” but also to take things a bit further than that.

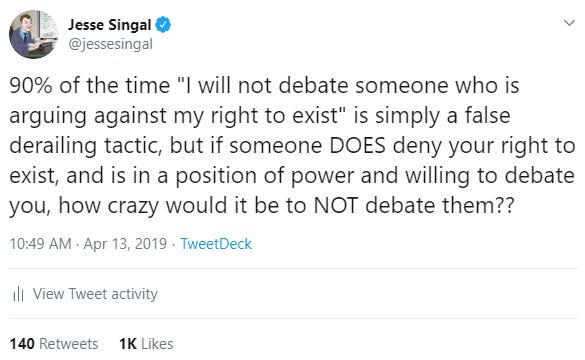

So: slalom punditry. Back in April, TNR published an article by Josephine Livingstone (who uses they pronouns) that was mostly a broadside directed against me and my work. Livingstone was mad about some tweets of mine in which I argued against the line, often uttered by my fellow progressives and leftists, that one shouldn’t “debate [one’s] right to exist.”

Elsewhere, I pointed out that former slaves had rather assertively argued for their own humanity, Frederick Douglass being the obvious example, though there are others, as well. This caused a bit of a Twitter blowup and I made my argument in a bit more detail here, for what it’s worth. (In my view, a lot of people on Twitter have oversimplified Douglass’s view on the possibilities and limitations of public discourse — at various points he has uttered quotes pointing in near-opposite directions — so in the post I tried to explain some of that.)

Anyway, in Livingstone’s article, they jump off from my tweet to attempt a searing indictment of my work on youth gender dysphoria, particularly my story in The Atlantic about what the diagnostic processes for dysphoric young people seeking out puberty blockers and hormones and (less frequently) surgery should look like. First, Livingstone claims that I believe “debate is an axiomatic good,” which is an argument I’ve made exactly nowhere — Livingstone’s editor refused to correct this, claiming in an email it was a matter of ‘interpretation.’ That is, Livingstone read a tweet of mine in which I said that debate about difficult issues is good under certain circumstances, ‘interpreted’ it as my saying debate on difficult issues is good under every circumstance, and publicly attributed the latter view to me. Journalism!

There are a bunch of similarly nonsensical claims in this very strange article. “Singal compared the experience of trans people to enslaved black people in the antebellum era.” Never happened, anywhere — completely made-up. “His logic[on trans issues] is circular, and obsessive.” Where? What circular logic have I employed? Livingstone doesn’t say. “In returning to the subject repeatedly, Singal seems intent on cracking some truth about the trans experience that is not accessible to him, as if provoked by that very inaccessibility.” Well, no — almost everything I’ve written on this subject has to do with specific clinical controversies about how to help alleviate the suffering of young people with gender dysphoria. I don’t think there’s any single “trans experience” to crack, nor would I attempt such a cracking.

Elsewhere, Livingstone writes:

Singal and others who are critical of the social justice left—a group that ranges across the ideological spectrum and includes Bari Weiss, Ben Shapiro, Daphne Merkin, and Katie Roiphe—accuse the left of being footstampingly insistent on their views, to the detriment of healthy debate. In fact, it is the “debate me, coward” crowd that has made it impossible to have arguments in good faith, because they demand, unwittingly or not, to set the terms.

I have no idea what any of this means. I have no idea when I have ever demanded someone debate me, as opposed to asking critics to clarify exactly what they disagree with me about, and proposing genuine conversation rather than Twitter-sniping or — just to take a hypothetical example — bad-faith attempted-takedown articles. I have no idea why I’m being lumped in with a group that includes Ben Shapiro, someone with whom I disagree about almost everything, or what I could have possibly done to make it “impossible to have arguments in good faith” — such power I apparently have! I have no idea what ‘terms’ I have demanded to ‘set.’ None of this is explained at all. It’s treated as obvious, on its face, what Livingstone is saying, because they are writing for a set of readers who will have a pavlovian reaction to names like Ben Shapiro and Bari Weiss and to buzz-phrases like “debate me, coward,” who will nod along and cheer without attending to the specifics. But to the reader unfamiliar with these culture wars, it must come across as very confusing. What does it even mean for one group to “make it impossible” for everyone else to have good-faith arguments? How would the mechanics of that even work? If someone demands to set the terms of a debate, why not simply tell them to fuck off, that you don’t want them as a debate partner? Every time I reread this paragraph I get more confused.

And on and on and on. Livingstone manages to write hundreds of words about me without ever engaging with the actual substance of my own thousands of words on this subject. The general sense the sympathetic reader gets is one of some grand debunking — there’s the real veneer of moral force, of common sense, of truth-telling in Livingstone’s writing — but at no point does any non-caricatured version my work make even a brief cameo appearance.

That’s why I’m partial to the “slalom punditry” metaphor. Livingstone zooms downhill in their article, deftly evading any of the questions that might slow them down. Do they think 12-year-olds should be granted full medical autonomy, or they think that there might there be situations where clinicians should slow down or question a young patient’s desire to physically transition? Whoosh, and it’s gone. Does Livingstone disagree with the American Psychological Association, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Endocrine Society, and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, all of which counsel some degree of caution about clinicians proceeding too hastily when working with gender-dysphoric youth seeking physical interventions? If so, what do they think these organizations are getting wrong? Whoosh, a featureless speck 500 feet uphill. Does Livingstone disagree with all the clinicians I got on the record echoing these concerns? Do they think detransitioners complaining about subpar care are lying? What would their preferred approach be when a 12-year-old decides in a sudden-seeming way they are transgender, in the midst of various mental-health problems? Whoosh, whoosh, whoosh. It’s like Livingstone has exactly zero interest in the actual lives of young transgender people seeking services, or the quality of the services they receive.

We can do the same thing with Nwanevu’s piece, because it’s the exact same style, even if it’s a bit more detailed and does make a bit more of a token effort to quote from his perceived opponents directly. Does Nwanevu really think social media hasn’t changed the nature of outrage at all? Whoosh, goodbye! Does he believe that media outlets aren’t doing anything wrong in their coverage of outrage stories? Whoosh. Does the ability of small, organized, angry groups of people on Twitter to affect the process of publishing young-adult fiction worry him at all? Whoosh. What about when it’s conservative video-game fans pressuring that industry? Whoosh. And so on.

This is a very downhill style of writing. And I suppose there’s a certain craft and skill to it, in the same sense that a speech delivered for a corrupt purpose can be beautiful or affecting — I can’t deny that. These essays are written for fellow culture-war partisans, not for anyone with conflicting or nuanced views on the subjects at hand. But I just think writers should do more: I like the idea of stopping, halfway downhill, to linger on some question or to admit uncertainty or to challenge my readers. I think that style produces much better journalism and commentary and criticism than what is being peddled by Nwanevu and Livingstone and a larger and larger chunk of left-of-center journalism. This isn’t the fault of individuals, necessarily — these articles themselves constitute a corner of outrage culture, and they’re relatively cheap to produce, and a solid writer can pull them off without having to go through the messy complexities of reporting or engaging with and reflecting upon complicated events and ideas. Journalism’s ongoing collapse is going to continue causing things to trend in this direction.

But this style is boring and it makes the conversation dumber. No one who reads Nwanevu’s article who is a neophyte to the “cancel culture” discussion will think there is anything to debate there, because Nwanevu slaloms past all the potentially important points, often obscuring them from his readers rather willfully (I may have just mixed metaphors, but we’re about 10,000 words in so please forgive me). No one who reads Livingstone’s piece who is unfamiliar with the subject will understand that there is a complicated debate playing out across our broken health-care system about how to help gender-dysphoric youth and detransitioners, because Livingstone pretends that conversation doesn’t exist — instead, what matters here is “the epistemological challenge that trans culture lays at cis culture’s doorstep: You must trust me to know my own identity,” as though that’s a meaningful statement with an obvious interpretation when applied to an adolescent in the throes of a period of rapid development, mental-health problems, or both.

I’ll repeat myself: This is a fundamentally bankrupt way of doing journalism and criticism, and it should be treated as such. It’s also a wasted opportunity. Nwanevu and Livingstone are intelligent, passionate professional writers at one of the top publications in the country. Surely if they engaged with these issues more seriously, they could advance the conversation in useful ways. For instance, it can’t be that Nwanevu is unaware of the incidents I highlighted further up. So I’ll repeat: What does he think of them? It could, for example, be that he thinks Breitbart was within its rights to shine a brutal spotlight on Monica Foy for making a joke about a dead cop, and that that’s just the world we live in now — sometimes you make a bad Twitter-joke and a bunch of people drive you from your home with rape and murder threats, and there’s nothing to really be done about it. But without hearing Nwanevu’s thoughts on the sorts of incidents that motivate thoughtful critics of “cancel culture” like Jon Ronson to write about this subject, there’s no way to know if this is his view.

Similarly, Livingstone skis pretty close to making an argument that trans 12-year-olds should have full medical autonomy. Or at least that’s how I interpret the line “You must trust me to know my own identity” when raised in the context of my work on gender dysphoria, which has always focused on minors. It would be really, really interesting for Livingstone to use The New Republic to lay out this argument more directly — surely it would be a provocative piece in light of our contemporary understanding of developmental psychology and medical ethics. What would the Josephine Livingstone article “Trans 12-Year-Olds Should Be Able To Make Their Own Medical Decisions” look like? Upon which premises would it rest? We don’t know, because they didn’t actually engage in the on-the-ground discussion about trans kids and blockers and hormones. (In fact, I can’t find anything that Livingstone has ever written that even contains the term “gender dysphoria” — this appears to be an entirely new issue for them, journalistically, and possibly one where they haven’t done any actual reporting or research.)

Of course there could also be downsides to Nwanevu or Livingstone grappling with these subjects in a more substantive way: They’d have to stake out actual positions on issues that aren’t so cut-and-try, and which often defeat the overly simplistic culture-war frameworks which render clear which side you’re ‘supposed to be’ on. It’s a scary challenge to do that, but it’s rewarding — it’s what makes being a writer worthwhile in the first place.

I think they should go for it.

Questions? Comments? Rants about the ranting ranters ranting at ranters? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Photo by Victoire Joncheray, from Unsplash.

The fact of the matter is that this sort of disingenuous think-piece essentially saying "nothing to see here" has been going on regarding so many of these culture war issues, for at least 6-7 years. It's been going on regarding the censorship/free speech in academia issue. It's been going on regarding the general issue of political correctness run amok. It's been going on regarding how vindictive and pathological call-out culture has become. It's been going on regarding trans activism. It's been going on regarding the growing language policing. Anytime a nuanced critique of these extremist positions and tactics is raised, you have these dishonest voices dismissing the critiques with something akin to, "These critics are really just a bunch of horrible bigots wanting to be offensive without repercussion. Cf. Milo!"

For me, this is all really frustrating to deal with, not just because I disagree with their positions, but because I strongly believe that it's important to hear honest criticism of one's own positions. But these critiques are rarely honest. They misrepresent the cases, deny facts, selectively quote, and generally obfuscate the issue in order to bolster their regressive viewpoints. After seeing this sort of bad-faith feedback enough, one tends to just tune out criticisms of one's views entirely, realizing it's a waste of time to spend one's energy engaging with dishonest actors. But that isn't an intellectually healthy approach either.

I don't have a solution, just laying out my thoughts.

Before they became progressives, liberals called "cancel culture" blacklisting-- and hated it. Then again, liberals used to believe in free speech and due process.