Three Arguments I, An Unapologetic Free-Speech Bro, Am Not Making About Free Speech

Let's dissect these mantras so as to elicit some deserved eye-rolling

In Today’s Newsletter:

-A Book Giveaway (Short)

-What Was In The Paid Newsletter Last Week (Short)

-Three Arguments I, An Unapologetic Free-Speech Bro, Am Not Making About Free Speech (3,400ish words)

Book Giveaway: Clear and Present Safety: The World Has Never Been Better and Why That Matters to Americans by Michael A. Cohen and Micah Zenko

This looks like a timely and provocative book:

What most frightens the average American? Terrorism. North Korea. Iran. But what if none of these are probable or consequential threats to America? What if the world today is safer, freer, wealthier, healthier, and better educated than ever before? What if the real dangers to Americans are noncommunicable diseases, gun violence, drug overdoses—even hospital infections? In this compelling look at what they call the “Threat‑Industrial Complex,” Michael A. Cohen and Micah Zenko explain why politicians, policy analysts, academics, and journalists are misleading Americans about foreign threats and ignoring more serious national security challenges at home. Cohen and Zenko argue that we should ignore Washington’s threat‑mongering and focus instead on furthering extraordinary global advances in human development and economic and political cooperation. At home, we should focus on that which actually harms us and undermines our quality of life: substandard schools and healthcare, inadequate infrastructure, gun violence, income inequality, and political paralysis.

I’ve got two copies for Singal-Minded subscribers, free or paid, who send an email with the subject line ‘safety’ to singalmind@gmail.com. Send those emails! (Disclosure: I know one of the coauthors, Michael Cohen, a little. We’ve probably met three or four times in person over the years.)

Oh, and the Q&A with Alice Robb, author of Why We Dream: The Transformative Power of Our Nightly Journey, is going to happen next Monday rather than today, as was originally planned. Sorry for the delay but thank you to the many people who sent in questions.

What Was In The Paid Newsletter Last Week

On Wednesday, I published a post, pegged to a new study, on a subtle way in which the implicit association test could be shown to be ‘effective’ despite a fair amount of evidence that it doesn’t really measure what it purports to be measuring. And on Friday I argued that the Ilhan Omar controversy is an example of right-wing offense archaeology, and lamented the social-media-driven tendency to search for superficial stuff to get deeply offended by, which is continuing to make us all dumber at an alarming rate.

Non-subscribers, imagine how much richer your life would be if you had read these posts! “They were not too bad, overall, I suppose?,” said a friend of mine who may or may not exist and who will remain anonymous. The glowing endorsements keep flooding in!

If you want to subscribe, here you go:

Three Arguments I, An Unapologetic Free-Speech Bro, Am Not Making About Free Speech

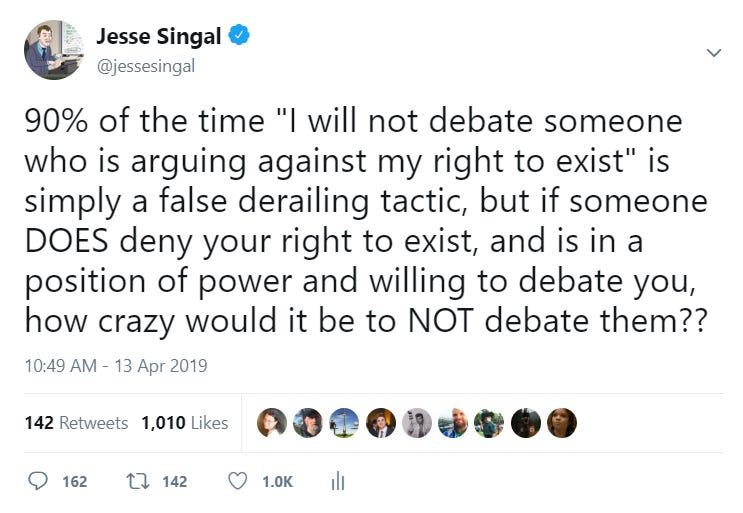

Over the weekend I got in a pointless Twitter blowup by arguing against the idea that people should automatically refuse to engage in political conversation with those who don’t recognize their humanity.

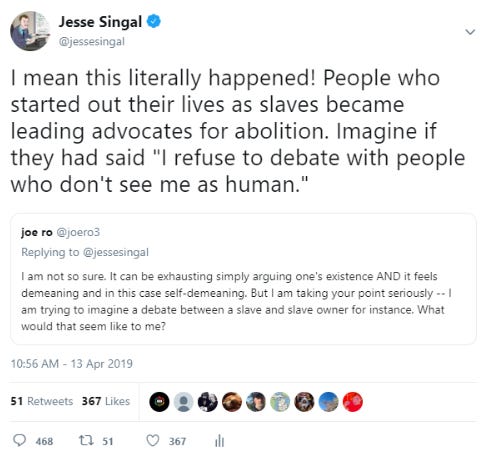

I followed that up with this tweet, obviously with Frederick Douglass in mind:

I ended up deleting the second one because it attracted so many angry responses. Which of course it was going to! Do not casually express opinions on fraught subjects that require a lot of caveating and explaining on Twitter — it is a poor platform for that. This is a lesson I keep failing to learn, so I can’t really blame anyone but myself for the mini-blowup that followed. I also focused too much on the word ‘debate’ in both tweets, when I should have leaned more heavily on the broader concept of “political engagement,” or something like that (‘debate’ has certain online baggage associated with it that I’ll explain later).

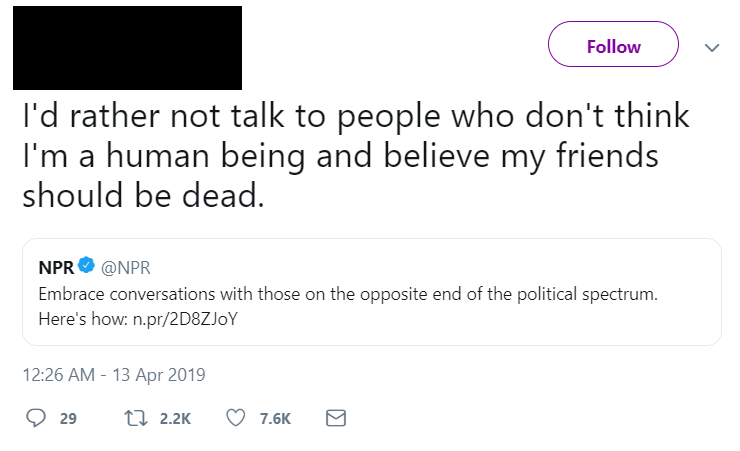

Now, the whole reason I brought any of this up is because “I will not debate my right to exist” and its variants appear, at the moment, to be pretty common utterances. To take one of a million examples:

(As a general rule, I’m going to shield the identities of Twitter-folk who don’t have much of a platform, but keep the names in of writers and others who do — it’s a public platform, after all.)

Often, this is presented not only as a justification for refusing to engage with vilest-of-the-vile figures like Nazis, but is also applied to a wide variety of conservative figures, too. Another random example from memory, this one from a group of student activists: “If engaged, Heather Mac Donald would not be debating on mere difference of opinion, but the right of Black people to exist.” You may disagree with Heather Mac Donald’s views on policing or Black Lives Matter or whatever else, but she definitely is not saying that black people do not have the right to exist, and none of her arguments lead logically to that claim.

I definitely spend too much time on Twitter, so it could be that beyond that platform and activist hothouses like some college campuses, few people are using this line of argument to avoid political engagement. Either way, what I realized, in reading the responses to my tweets, was that many of those responses weren’t geared toward my particular argument. Rather, they were mantras that seem to get chanted whenever someone makes any liberal case for free speech, intellectual engagement with one’s political adversaries, or both. They’re recited even when they don’t really apply, as though it’s simply that time in the ceremony.

These mantras end up derailing things and preventing meaningful left-of-center dialogue on free speech and related issues. So I think one potentially useful way of salvaging my Twitter misadventure is to lay out, as clearly as possible, what I am not saying when I make arguments in favor of free speech or political engagement between those who disagree on vital subjects. Maybe my own views are right and maybe they’re wrong, but we’d all be better off if people rolled their eyes when they encountered these mantra-responses rather than treating them like substantive counterarguments.

Now, I can’t speak for anyone else who is free speechy, but once again: I hear these mantras all the time, in many different contexts. I would bet that in the three subheadlines that follow, one could replace “I am not…” with “People with liberal views on free speech are not…,” and things would stay pretty accurate.

I am not arguing that debate solves everything.

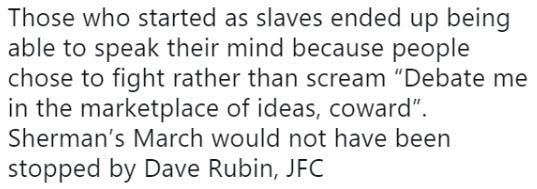

Here were a couple of the responses I got over the weekend:

And this one from a professional journalist:

And this one from a professional academic philosopher:

I see this claim, that free-speech advocates believe that debate can solve everything, all the time. In this case, I am (apparently!) being accused of claiming that civil debate alone could have ended slavery without the Civil War, or something.

That would obviously be a silly argument given how history played out. But it would also be a silly argument to pretend abolitionism as an intellectual and activist movement didn’t play an important role in the eventual undoing of slavery as well, or that part (not all) of what someone like Frederick Douglass was trying to do was influence the opinions of people who did not, in fact, recognize his full humanity, or that other countries with slavery didn’t abolish it peacefully, in part because of the efforts of activists whose saw persuasion as one of their goals, even if the full story was always more complicated than persuasion alone.

Questions surrounding what Douglass did and didn’t believe on this front caused a whole other set of Twitter spinoff debates over the weekend — this is tangential to the main point of my post but too interesting to not give it a few paragraphs. The tweet the above philosopher was referring too, and many others, referred to this speech, delivered in Rochester in 1852, which was used to defend the idea that of course Douglass was against the idea of debating his humanity itself:

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? That he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the wrongfulness of slavery? … To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your understanding.

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash, to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction, to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? …

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.

But in this other speech, from eight years later, he portrayed free speech itself as capable of destroying slavery: “Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South.” And prior to delivering either speech, he wrote and published a famous, white-hot letter to his own former owner, which, while not a ‘debate,’ is the very dictionary definition of engaging with someone who doesn’t view you as fully human, even if the goal in that case wasn’t to persuade him but to persuade and mobilize others.

These were specific arguments given in specific contexts to specific audiences, and there were reasons for the rhetorical flourishes Douglass included in each — I think it’s a mistake to overextrapolate from one or the other or to take literally the claim that free speech alone could have ended slavery. But even in the speech in which Douglass was mocking the ridiculousness of having to engage on the question of slavery’s horror given its self-evident nature, he was… trying to convince a mostly white, moderation-inclined audience to take those horrors more seriously. Engaging through ridicule and moral suasion is, of course, still engaging, and it’s undoubtedly the case that some in the audience didn’t understand the full horrors of slavery. So I don’t really see how even this speech supports the idea that Douglass had anything like the equivalent of a modern, I won’t engage with those who dehumanize me! stance. (For those who want to learn more, the first link above is to a great Slate article that provides plenty of context for the Rochester speech, and the second is to a transcript that itself contains all the context one needs to situate that one.)

Anyway, the “You think debate can solve everything? Idiot!” rejoinder is usually deployed in the context of morally egregious episodes like the Holocaust or American slavery to monster the positions of free-speech advocates without engaging with them. It’s strawmanning, basically — Debate can solve everything! is a much easier position to knock down than the arguments about free speech and political engagement that actually get made. But of course I’m not arguing that, and I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anyone argue that anywhere, to be honest.

I am not arguing that people in vulnerable positions, or anyone else, should be forced to debate fraught issues with anyone who insists on doing so.

Another mantra that gets recited whenever free-speech issues come up is that it’s unfair to ask marginalized people to defend their own existence (or language to that effect):

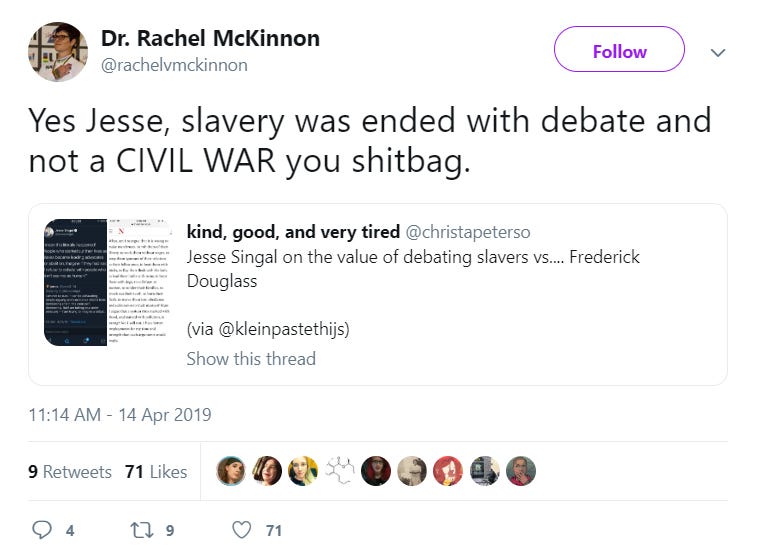

One journalist took it further — he helpfully pointed out it could be dangerous for Douglass to literally debate a slaveowner on a plantation (which, thanks!):

This is another area where I simply get confused as to who, exactly, is making the arguments being attributed to the pro-engagement side of the debate. When I said that former slaves, Douglass among them, advocated for their own humanity, I obviously wasn’t saying that this means they felt an obligation to put themselves in danger or to debate any random slavery-lover who showed up. The point was broader than that. Likewise, when I say that Palestinians shouldn’t use the fact that some Israelis dehumanize them as justification to not engage with and attempt to sway Israeli public opinion, or that Uighur activists shouldn’t use their own beyond-horrific marginalization as an excuse to not advocate forcefully for their humanity to Chinese audiences, it goes without saying — or it should go without saying, unless you’re trying to derail the conversation rather than understand my position — that this does not mean I think members of these groups should engage in a manner which would put them at immediate risk, or in situations in which they would have nothing to gain by doing so. There was a reason even in my too-debatey, too-hypothetical first tweet, I specified that I was only referring to situations in which the potential ‘debate’ partner has power and is therefore, arguably, worth debating with in the first place.

I think this mantra about supposed free-speech bros trying to force marginalized people to debate with bigots has flourished for two reasons: one is simply bad-faith strawmanning, and the other has to do with the nature of social media. The strawmanning reason is simple: Again, it backs the free-speech advocate into the corner of appearing to be arguing for a really dumb, harmful position. If, in fact, my claim was that (say) every Jewish person is obligated to engage in debate with every anti-Semitic person they come across — or that escaped slaves should try to return to the plantations they escaped from for the sake of The Discourse! —then this would be a remarkably dumb argument, not to mention one that would force me to cancel my book to spend my every waking hour debating CuckFuhrer1488 et al online. Pretending free-speech advocates are saying this is simply an easy way, again, to discount their arguments sans genuine engagement with them.

There’s a more good-faith flavor of this claim, though. For a lot of people, these days, political debate means online debate, and online debate means Twitter. On Twitter, you do get a lot of random people, bigots and otherwise, trying to force you to have some sort of debate with them. This gets quite annoying, fast. And of course no one should ever feel any obligation to debate someone simply because that person has popped up, demanding a debate. The Debate Me Bro caricature exists for a reason — there are a lot of Debate Me Bros out there, gunking up people’s Twitter mentions. So I think a subset of people, when they hear “Political engagement and conversation are important, even on sensitive subjects,” are thinking of all the idiots who pop up in their Twitter mentions and saying to themselves, “Wait, you want me to debate CuckFuhrer1488 about his theory that Jews have differently shaped skulls?”

This is an area where those of us who find ourselves arguing for free speechy positions should do a bit of a better job specifying exactly what we mean. For example, my view is that if you are a public thinker type, like a journalist or an academic or someone in that wheelhouse, you do have some level of obligation to seek out and engage with those who disagree with you honestly and transparently. Or at least I don’t know what it means to be a public thinker type if you don’t do that sort of thing. But I’m not saying anyone has any particular obligation to debate anyone else.

I am not arguing that many or most people are persuadable via reasoned discussion alone.

Free speech fans are constantly accused of taking the naive position that if only people had access to the right facts and information — delivered via civil discussion, of course — Bad People would change their minds, becoming Good People. It’s as if we are arguing that more open conversation with Nazis about race science would cause said Nazis to metamorphose into pacifistic hippies from the sheer force of our Logic and Reason.

Persuasion itself is an endlessly complicated subject. To a certain approximation, on hot-button issues, people aren’t all that persuadable. And there’s definitely no one recipe for effective persuasion. My favorite effective-persuasion study, my writeup of which I link to all the time, involves trans issues, and on that one, people likely weren’t really swayed by some deeply insightful new slice of logic, but simply by being prompted to reflect a bit on how trans people’s situations might not be entirely different from their own, in a certain zoomed-out sense. It was more personal and visceral than logical, in other words.

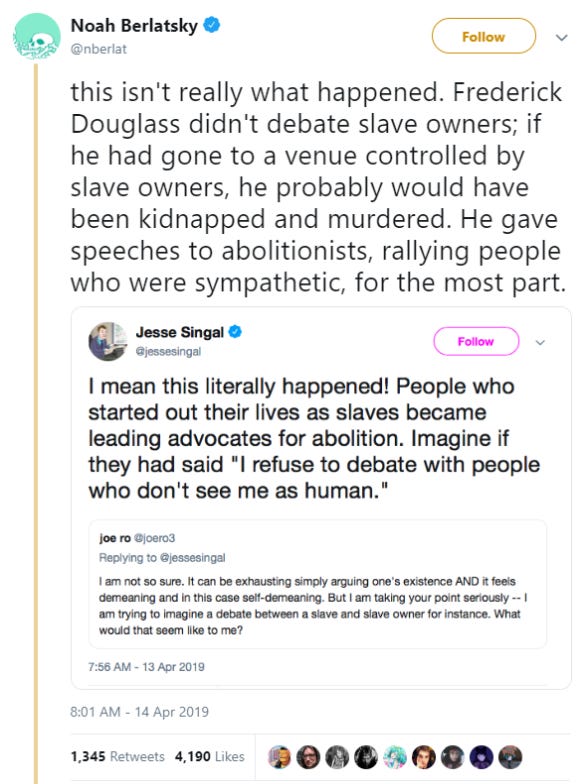

So as someone who once wrote an article headlined “Awareness Is Overrated,” far be it from me to argue that new information or argumentation, on their own, sway people all that often. But I think they do play a role. American history is rife with dramatic, relatively short-term changes in public opinion on extremely important issues, as this chart on whites’ racial attitudes shows:

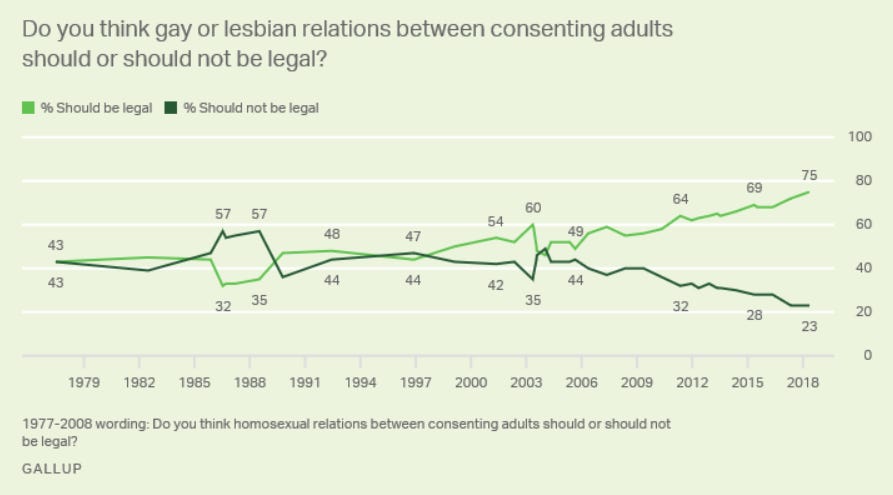

Or this one, on attitudes toward gay sex:

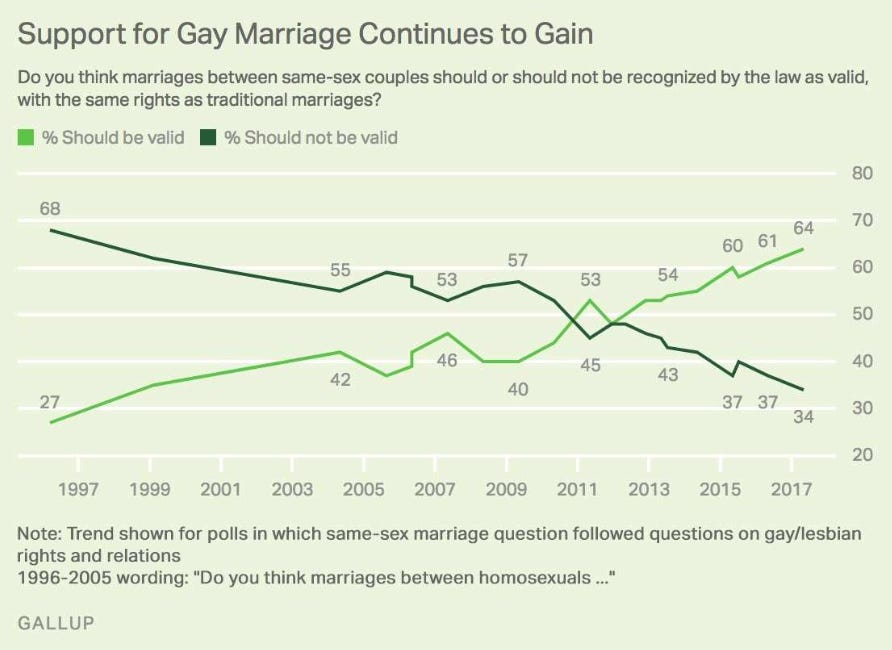

Or this one, on attitudes toward gay marriage:

And so on.

What’s going on when this happens? How much of it is ‘traditional’ persuasion versus a host of other factors working in concert? No one knows. I think the most likely general model is that people change their minds primarily because of social influences, including the development of meaningful relationships with members of the groups in question — the contact hypothesis, in other words, though see this less optimistic take, too — or slowly coming to realize their own community will no longer tolerate their old attitude. Then, after the individual changes their mind, they explain what happened in a bit of a fancier-sounding way. It may sound like they were ‘persuaded,’ in other words, even when that’s not exactly what happened.

But having open discussion of these issues, carried out by compelling figures, is really, really important. Somewhere along the way, if you go from being in favor of segregated schools to being against them, or from being against gay marriage to being for it, you will need to develop a logical-ish explanation for your views. And it’s likely that the process can be hastened by particularly effective exemplars of civil rights positions.

Again, I think people put too much weight on that concept of debate in its purest, prep-schooliest form. What matters more is engagement. To have a member of a hated group show up to an event and passionately, eloquently defend her humanity is a form of engagement, of pushing one’s way into a conversation from which one has previously been excluded. It doesn’t always work and it isn’t a social-justice panacea, but it needs to be part of the process, and to discount its efficacy entirely would be unwise. There’s a reason part (not all) of every single civil-rights struggle consists of simply carving out a place in the discourse.

Douglass’s free-speech speech, for example, was delivered in response to a group of thugs successfully dispersing an abolitionist event in Boston:

The world knows that last Monday a meeting assembled to discuss the question: “How Shall Slavery Be Abolished?” The world also knows that that meeting was invaded, insulted, captured by a mob of gentlemen, and thereafter broken up and dispersed by the order of the mayor, who refused to protect it, though called upon to do so. If this had been a mere outbreak of passion and prejudice among the baser sort, maddened by rum and hounded on by some wily politician to serve some immediate purpose, - a mere exceptional affair, - it might be allowed to rest with what has already been said. But the leaders of the mob were gentlemen. They were men who pride themselves upon their respect for law and order.

Do people really think this sort of thing is totally pointless? That no pro-slavery or ‘moderate’ 19th-century Bostonian could ever have been swayed by the growing salience of abolitionist arguments in his daily life? Why? Why did Douglass make such a big deal about it if he thought engagement was futile? Why was the “mob of gentlemen” — one serious pleasure of this weekend was re-reading speeches I haven’t read in a very long time — so threatened by the event’s mere existence? Maybe in the everyday din of things we don’t see a lot of persuasion, but those charts above aren’t just the result of older, more conservative generations being supplanted by newer, more liberal ones, or of already-sympathetic people being mobilized. There’s obviously some persuasion going on, even if that isn’t the most common outcome of a given instance of political disagreement.

People are a little too confident in their ability to judge whether a given individual’s views are or aren’t going to change over time. There’s a lot of faith that humans, as though equipped with fancy moral X-ray machines, can distinguish Merely Misguided people (who are worth engaging with) from Bad People (who are not), which has the effect of treating those categories as immutable. But they aren’t — not always. The above charts translate to tens of millions of people changing their minds. There are hardened racists who become tolerant enough, people who are tolerant enough who become passionate advocates, tolerant people who backslide into intolerant positions, and every other combination imaginable. Everyone’s different, and there’s some seriously unearned hubris in the idea that we, schmucks and sinners all, can extract perfect information about the heart of another and, on the basis of this diagnosis, confidently hurl them into a pile of moral untouchables.

I hate that idea. It smacks of a profound lack of curiosity about how human beings work, and a willful ignorance of our deep, if often untapped, potential to be and to do better.

***

The point of running through these three mantras is to try to prevent this conversation from falling into the same ruts every single time it pops up. It never seems to get anywhere. I guess “I want to improve the way we argue about this” is in fact a very free-speechy sentiment, and the burgeoning group of people on the left who are suspicious of the very concept of free speech itself aren’t going to be swayed by it, but still: If you are skeptical of pro-free-speech and pro-intellectual-engagement claims, you should stop reciting these mantras, at least until you can provide evidence of important people making arguments like “I think random black people on Twitter should be forced to drop what they are doing and debate KKK members.” If you are a journalist or other public thinker in this camp, you should definitely stop reciting these mantras, because to continue doing so in the absence of evidence is intellectually dishonest. If we’re going to talk about this stuff, we should do so in a good-faith way. Or maybe it’s too late — maybe Donald Trump and Twitter and everything else have melted everyone’s brains so profoundly that even people who really do agree on a great deal can no longer have a normal, semi-functional conversation about one of the oldest and most important concepts in American life.

That would be a shame.

Questions? Comments? Complex legal arguments about how this newsletter meets the legal threshold for incitement? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The lead image, a Lincoln-Douglas debate stamp, is from Wikimedia Commons.

To some extent, isn't part of the problem what you think is the "invisible hand" of the "marketplace of ideas"?

If you're all-in on "social pressure is the invisible hand", then you're likely to believe that ostracism (or even censorship) of the opponents is the winning strategy. You're likely to be more concerned about the unequalness of the playing field causing a chilling effect on marginalized people, than you are about the traditional legal arguments protecting freedom of speech (including "hate speech" or "dehumanizing speech"). You would also be likely to believe that your opponent has come to a similar conclusion and be concerned that a denial of a "right to exist" is fundamentally your opponent's goal. Honestly, I blame literally everything on blank-slatism and social constructionism, so I genuinely assume that most people who are against debate and free speech think along this line, but am probably provably wrong.

If you're all-in on a "free speech is the invisible hand" side, you're likely to get strawmanned by any of these three. Debate isn't magic that solves everything, but it's incredibly powerful. Whether its power comes from public mockery of bad ideas, moral high ground, awareness of serious problems, FACTS and LOGIC, persuasion and mobilzation, contact with and sympathy towards differing groups, or some other source... explaining the exact mechanism by which debate will solve the problem is not necessary because the market will figure it out (mostly). Obviously, not knowing the exact mechanism for the specific situation can lead to a perception of it as "the naive position that if only people had access to the right facts and information — delivered via civil discussion, of course — Bad People would change their minds, becoming Good People". Also, there's no real reason that a specific instance will be recognized as good at all, but somehow each individual twitter shitpost will be work toward a public interest.

If we buy into this dichotomy I asserted without any real evidence, I think that the "free speech is the invisible hand" people are right, but at an important strategic disadvantage. It's very easy for anti-debaters to cite specific examples of where they were right and the exact mechanism for them being right, and much harder for debaters to prove that allowing debate completely at will is good for society as a whole. We, in general, know that people don't particularly care about facts in the body of a post as much as moral claims in the headline. A bad popular idea is often 10 times stronger than a little-known right one. We know from people like Christian Picciolini and Daryl Davis that conversations can deradicalize white nationalists, but there's a lot of heat on Twitter and YouTube to deplatform the "Alternative Influence Network" who are apparently radicalising the kids because they interviewed Milo Yiannopolis and Candace Owens. Honestly, I can't comprehend someone being more in favor of Owens after hearing her speak, but I'm proven wrong every single time.