The Risk Of Progressives Talking Over Marginalized Communities

What does it mean to say you're trying to protect a group when its members say they don't require your protection?

(My last day in Los Angeles, I went for a hike with my oldest friend and his very cute, very chatty 2-year-old, who rode in one of those backpack-things. It was all uphill for the first half or so of the hike, and near its apex, this was the view — it was rare, my friend said, for the LA air to be so clear one could see all the way to the Pacific, and he said the fact that it had been raining most of the week was likely the reason why.)

As you likely know, a scandal recently exploded when it was revealed that Virginia’s Democratic governor, Ralph Northam, appeared in a medical-school yearbook photo wearing blackface at a party — part of an apparent gag (maybe insert air quotes) in which he dressed as a black man and a friend of his as a Ku Klux Klan member. This led to as-yet-unheeded calls for Northam’s resignation from a rather large, bipartisan group of politicians and activists and pundits. “Black People Elected You, Northam. And You Betrayed Us,” went a representative Daily Beast headline affixed to a column by Goldie Taylor.

But there was a bit of a plot twist last week. According to a Washington Post/Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University poll summarized by WJLA, “Only 37 percent of African Americans [in Virginia] say Northam should resign compared to 58 percent who say he should not. African Americans approve of the job Northam is doing by 58-30 percent and accept his apology by a 58-31 margin.” In polling, a 27-point difference is quite large — in this case it translates to about a 2:1 gap, meaning members of the single group ostensibly most affected by Northam’s donning of blackface believe rather strongly that he should stay in power despite it.

This story ties into one of my qualms about the way progressives talk about race, and marginalized groups in general, these days: It feels increasingly common for progressives to treat the opinions of elite members of marginalized groups as representative of the groups in question — even though rank-and-file members without platforms may feel quite differently.

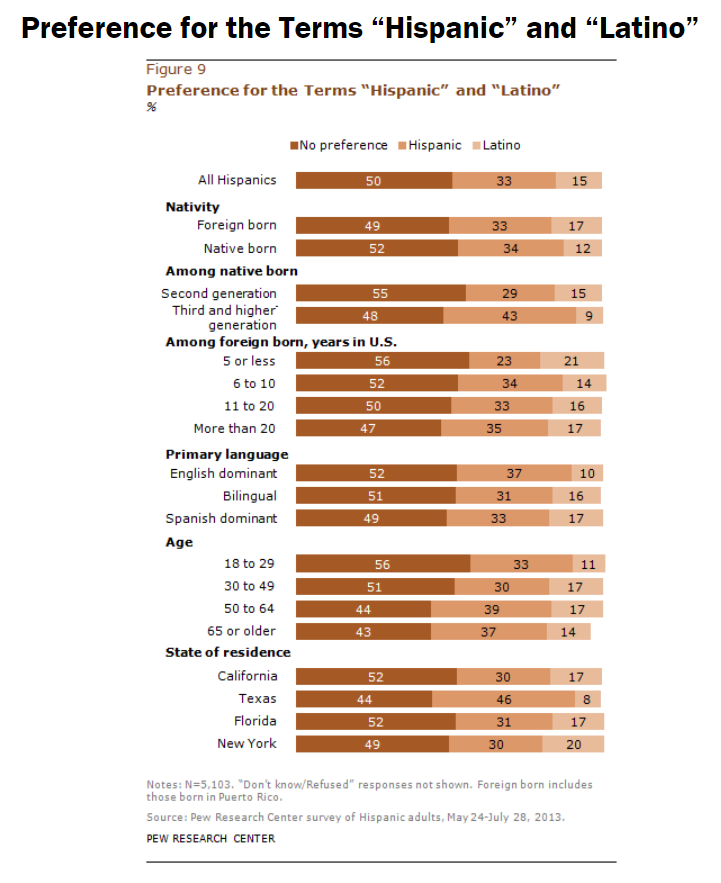

Some other examples of this: Many progressives, Latino and non-Latino alike, seem to have rather strong linguistic preferences about whether to use the word Hispanic as opposed to Latino (or, more recently, Latinx). But when actual, well, Latinos/Hispanics are polled on this question, their answer tends to be that they identify more with their country of origin or ancestry than with zoomed-out ethnic labels anyway, with only about half of members of these groups even having a preference — meaning it doesn’t make much sense for anyone to suggest one term or the other is “right” while the other is outdated or offensive:

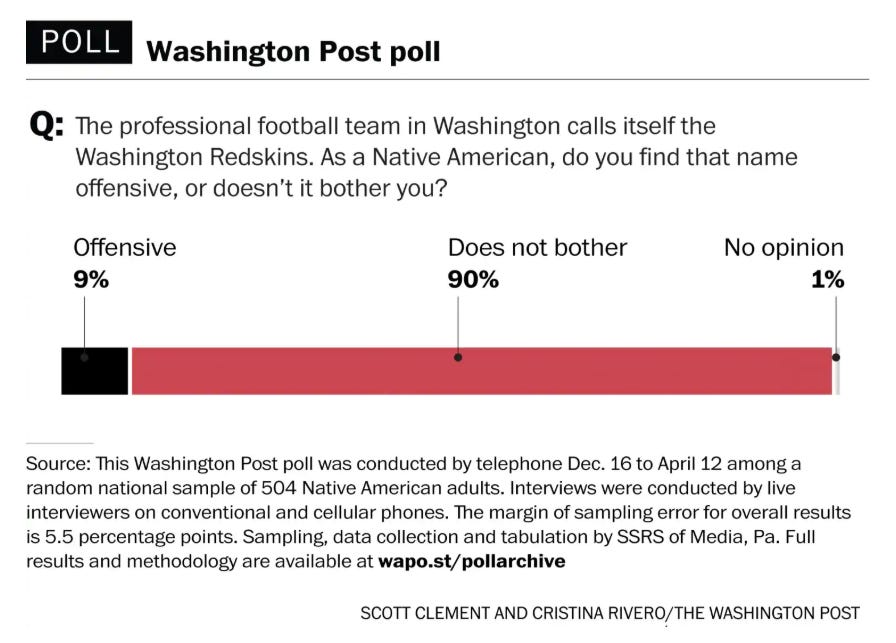

There’s something similar going on with a controversy that, to me, is a much easier call: the Washington, erm, football team. I’m of the belief that the logo and name are offensive and should absolutely be changed. Which, it turns out, is an opinion held by a mere 9% of actual Native Americans, according to a 2016 Washington Post poll:

(Interestingly, according to the Post, that number hadn’t budged since the last time the question had been asked, in 2004, by a different polling outfit — despite a great deal of activism and awareness-raising between the two surveys.)

Now, does the fact that a solid majority of black Virginians want Northam to stay mean that he definitely should, and does the fact that an overwhelming majority of Native Americans don’t find the Redskins name offensive* mean that it should? No — I don’t think that should be the end of either story. (* This section of the sentence originally read “overwhelming majority of Native Americans want the Redskins name to stay” — the bolded phrase was a misstatement of the survey result and has been edited.)

But at the same time, if you’re a progressive who is calling for the Washington football team to change its name, or for Ralph Northam to resign, because of the harm that football team name and that governor did to marginalized people, it should feel very weird that the actual groups most affected mostly disagree with you, no? Or if it doesn’t feel weird, why doesn’t it feel weird? What does it mean to say you hold an opinion out of a desire to protect a given group when members of that group say, in polling, they don’t require your protection on that particular issue?

The broader problem here is that progressive political elites have a bit of a class problem. They know how to speak the language of their fellow college-educated politicians and journalists and nonprofit-founders, who tend to have more progressive politics than just about everyone else, but sometimes stumble when it comes to their attempts to appeal to more blue-collar groups. That this is true when it comes to the white working class is a truism at this point, albeit a complicated one without an obvious solution — conservative whites in the U.S. are, on average, so conservative that it’s hard to argue in good faith a different progressive communication strategy could sway anything but a tiny subset of them. But what’s less appreciated and more rarely discussed is the extent to which this class problem extends to non-elite blacks, Latinos, and members of other minority groups, who are sometimes taken for granted simply because they vote so solidly Democratic.

A version of this popped up during the last presidential campaign. After Donald Trump was elected, the New York Times sent a reporter to a low-turnout, poor, African-American neighborhood of Milwaukee, and she found that many voters there were unenthused by Hillary Clinton and shared little to none of progressive-bubble America’s panic about the nightmarish prospect of a Trump presidency.

Here was one of the key points I pulled out from the article for my New York Magazine reaction to it:

The African-American Milwaukee voters were less outraged by Trump’s bigotry and misogyny than many optimistic Democrats expected them to be. Over and over, Democrats and journalists stated and wrote confidently that Trump’s outrageous statements about minority groups would fire up and turn out the Democratic base, making Trump’s uphill battle even steeper. It didn’t happen — exit polls suggest Clinton underperformed among African-Americans and Latinos. One interpretation is that members of these groups were, overall, less offended than bubble-denizens assumed they would be, or at least less mobilized by that offense. In the case of the Milwaukee voters [Sabrina] Tavernise interviewed (an admittedly nonscientific sample), Trump’s bigoted remarks just weren’t near the top of their list of concerns. One likely possibility is that African-Americans’ views on Trump were mediated by class and education. Just a month ago, the Times ran an article quoting a handful of the many black voters who were disturbed by Trump’s racial rhetoric. But it appeared to be a somewhat different crowd than the folks interviewed by Tavernise: Among the anti-Trump interviewees were a graduate student, another graduate student, a finance professional, and the head of a gay-rights group. It may be that high-information, politically engaged minority voters — those who are likely to have higher incomes and be better educated — found the choice obvious, but lower-information ones didn’t. It’s not like white people don’t have the same pattern.

This is reminiscent of how many Democrats approached the question of gender this cycle: The common thinking was that there was no way all that many women could possibly vote for someone with as extensive and explicit a record of misogyny as Trump, and that this would corrode the GOP’s usual base of white support. Again, the bubbles produced a spate of news stories reinforcing this belief: “Trump Is Losing Educated GOP Women—and Splitting Up Families Along the Way,” went the Politico headline. That was part of the basis for Chuck Schumer’s now infamous prediction that “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia.” But nope: White women broke quite solidly for Trump. Clinton got walloped by something like a 2-to-1 margin among white women without a college degree, according to one set of exit polls cited by Claire Malone of FiveThirtyEight, and only won those with college degrees — those respectable suburban types — by 6 points. The outrage was not as potent a force outside the bubbles as it was within them. [emphasis in the original]

So the risk of confidently proclaiming to know about “black opinion” or “female opinion” based on small, anecdotal, skewed elite samples is you might miss the bigger picture. Would you have ever imagined that only 9% of Native Americans find the Washington football team’s name offensive? Would you have ever imagined it was so easy to find African-Americans who don’t view it as obvious that Donald Trump is a much, much worse president for black people than Hillary Clinton would have been? If the answer to either question is no, it could be because you’re trapped in a bubble where, when you are exposed to black or Native opinion, it’s to a very specific type of black or Native opinion.

It’s possible to stretch this point too far, of course. African-Americans are still overwhelmingly Democratic — you won’t find any talk here about a secret black majority ready to vote GOP in the next election, because black GOP voters really are outliers. So in certain cases one can make rather confident statements about what African-American people — or members of other relatively politically homogeneous groups — prefer or value, as long as those statements are sufficiently broad. And when it comes to the 2016 election and black voters, we also can’t ignore voter suppression, which may have swung the election given how agonizingly close things were in so many crucial states (though on the other hand, had fewer Democratic voters, minority or otherwise, chosen to stay home, that also would have swung things in the other direction).

Anyway, on more specific issues like the Northam controversy, the key point here stands: Two very different questions — What are the views of members of marginalized groups? and What are the views of elite exemplars of marginalized groups whose opinions I am exposed to on cable news or on Twitter? — are being conflated by many people. And that’s a problem.

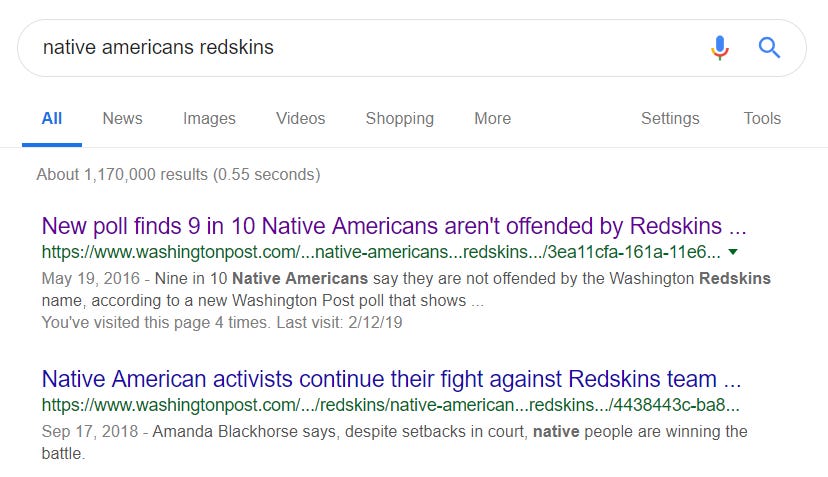

Maybe the best way to end this post is with a screenshot of the Google result that popped up when I tried to find the aforementioned poll of Native Americans:

So, a question for my non-Native-American readers: Does Native opinion matter to you? Which subset of it?

Questions? Comments? Unsolicited screeds about how the real story is the way the media is missing the heterogeneity of Scientologist opinion? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal.