It’s Best To Build Dams During The Dry Season

On mental health and learning from your regrets

The year 2022 was extremely difficult for me. That was when the full weight of my mom’s death, which occurred in April 2021, finally hit. In addition, my maternal grandmother died in May 2022. Combined with my paternal grandmother’s death, which occurred just a few days after my mom’s, I lost three of my four remaining parents or grandparents in about 13 months. To be honest, neither grandmother’s death was that unexpected, and both women were in their nineties, but it was still a lot of loss — I can’t help but think of that mawkish Arcade Fire line, “My family tree’s/losing all its leaves.” Plus, some other very bad stuff also happened last year.

Before wading into the swamp that follows, I do want to make it clear that overall, I’m doing okay. I have a lot that I’m looking forward to, including a couple of trips where I will get to hang out with people I love but hardly ever get to see. I might have a couple exciting work-related announcements to make soon, and I’m very lucky to have a rich and busy life. So while I’m struggling, the situation is manageable.

But things have been quite rough — perhaps rougher than they need to be. And I’ve been kicking myself a little that I didn’t pay more attention to my mental health when it would have been easier to do so.

I’ve written very little about my personal life over the years. It has never been my style, and I’ve kept my social media presence almost completely devoid of truly personal information (other than frequent disclosures pertaining to my addictions to, in order of declining severity, carbohydrates, the Boston Celtics, and Slay the Spire). I didn’t even say anything about my mom getting sick. My stance on this sort of sharing changed after she died, simply because it was the worst thing that ever happened to me and it didn’t feel like something I could keep private any longer. So I wrote and talked about it a little on the podcast and later, here (this is the only other example of such content I can think of off the top of my head, but I could be missing something).

My general attitude about this sort of writing and speaking is that I’m in no position to give people truly substantive positive suggestions about how to overcome grief or trauma or improve their mental health, except in the most milquetoast, here’s-what-the-science-suggests way. When I do enter this realm, I’m mostly doing so in the hope that it will make me feel a little bit better (YOU ARE MY UNWITTING THERAPISTS), that it will make other people going through similar issues feel a little bit less alone, and that in some cases, readers and listeners potentially can learn from my mistakes. I think it’s a lot easier to identify what not to do in these heavy areas than it is to figure out exactly the best ways to move forward. That’s what this post is about.

For most of my adult life I’ve been in a weird in-between space, mental health–wise. I’ve always known I had fairly significant tendencies toward anxiety and depression, but things never reached a crisis level. Perhaps because I had such a vivid example of serious depression waiting for me whenever I went home to Boston — in the form of a mom who couldn’t really get out of bed for long spells — I downplayed my own issues, which included a lot of intrusive thoughts, a lot of pathological-seeming rumination, and severe insomnia (more trouble falling asleep than staying asleep). Over the years I’ve just devoted far too much mental energy to, for example, being terrified at the sheer size of the universe and our insignificance within it (which is depressing, because when I was a kid I found astronomy and cosmology utterly fascinating rather than terrifying), ruminating about death, and the sort of tiresome, pointless metacognition where you beat yourself up over having thoughts you can’t control in the first place.

There’s nothing wrong with you if your brain occasionally dallies in these areas, of course — we are all human, and being a human is intrinsically weird and scary sometimes — but at a certain point, when you are recycling the same thoughts ad nauseam without generating any progress or insights… well, something is wrong, and you should see if you can fix it. That said, I was never suicidal. I’m being very intentional about noting that, because I do think anyone with frequent suicidal thoughts needs to seek help, if only to confirm that their suicidality is mild and not worsening, and to get a safety plan in place if that changes.

During my twenties and (rapidly diminishing) thirties, I had a lot of opportunities to try to figure out what I didn’t like about my brain and, to the extent possible, address those issues. I don’t think I would have been a candidate for medication, and I never wanted it, but why not some talk therapy (I did it only sporadically and never took it that seriously), or meditation, or even workbook-oriented cognitive behavioral exercises? I’m casting a wide net here because I have no idea what would have helped. That’s sort of the whole point: If you don’t try different things until you hit on something that works, at least a little, you’re not going to tweak your mind for the better.

Already I feel the Hedge Monster poking his head out of his burrow and whispering to me that I’m being too pat here and need to hedge. Okay, Hedge Monster. I’m not saying improving your mental health is like taking your car to the mechanic, where they will poke under the hood and identify the problem and loosen some crankshaft (?) (I know nothing about cars) and boom, problem solved. And for someone with really serious anxiety or depression, which I didn’t have back then, something more regimented than what I’m suggesting may be necessary.

But what I am saying is that if you’re unhappy with certain aspects of how your brain works (which I was) and have the resources to do something about it (which I did), you really need to act with intent. You can’t just hope things will get better, especially once you reach your mid-twenties and can no longer blame your problems on the lingering effects of the hyper-hormonal shitshow that is adolescence (I think a lot of people do simply grow out of mental health problems, luckily). And if you’re experiencing a fortunate spell where you don’t have a lot of external stressors or trauma going on, that’s a perfect time to do this sort of work. If you need to build a dam, it makes more sense to do so when the body of water in question is at a trickle.

I was pretty lucky during the first part of my life. Very little bad stuff happened. Yes, things got worse after my mom got really depressed, but that wasn’t until my late twenties, and the simple fact is that relative to the broader Human Experience, I did experience something of a cakewalk until recently. I’m not going to engage in extended self-flagellation over this, but if I could go back and do it again I would have said to myself, “Look, things are going to get rough at some point. You should use this time to figure out how to become a bit more resilient, and how to fight some of your worst cognitive tendencies, because then it will be a little bit easier to manage the worst stuff life can throw at you — which it will throw at you, because that happens to everyone, unfortunately.”

I think there were four main impediments to getting some help back then: One is that I have trouble with self-motivation when it comes to tasks I don’t find intrinsically rewarding, or that aren’t pegged to specific deadlines. You can always push off finding a therapist or trying meditation another week, and I often did.

Two is my general cynicism toward self-help and a lot of pop psychology in general. Now, there’s some decent evidence for talk therapy and CBT and meditation and (some types of) medication, and maybe I should have focused on that, but the fact is there is a ton of bad, and in some cases pernicious, self-help bullshit out there, a lot of jerks telling desperate people that if they can just “look on the bright side” or follow these Five Easy Steps, their problems will melt away miraculously.

I do want to become more resilient, but “resilience” discourse is a scientifically challenged mess. Not to toot my own horn, but just read my book chapter on Comprehensive Soldier Fitness, or read this excerpt if you don’t want to buy the book. It’s impossible to overstate how much money is wasted on feel-good nonsense. I think my revulsion at a lot of the self-help scene may have led to a degree of unhealthy overgeneralization, and I ignored the fact that yeah, there are hucksters, but there are also good and competent professionals doing the best they can to help people. The best and most honest advocates for meditations and CBT and other non-bunk mental health interventions don’t make infomercial-style promises; rather, they’re open about the fact that this whole thing can take a long time, and it’s not going to magically fix all of your problems and turn you into some sort of paragon of well-being. Dan Harris named his book 10% Happier because he thinks that’s how much meditation helped him — and he’s very grateful for it.

Three, and possibly most importantly: I had a really crippling inability to talk about serious issues with my friends, which is a shame because somehow along the way, despite being a weirdo, I did develop a lot of amazing friendships (even if I’m still mad at about a half-dozen of them for leaving New York for the West Coast in the last five years).

I could have talked to them about anything without fear of judgment, but I didn’t. Hell, I told only two people when my mom got electroconvulsive therapy for her depression, which at the time was the most jarring and destabilizing thing that had ever happened to me — and one of them lived thousands of miles away, and the other was a colleague who’s a great guy and a friend, but who I wasn’t that close with. Maybe this is an oversimplification but I don’t think this was an accident: I think I was genuinely scared of opening up and having a sustained conversation with my friends about how scared I was about my mom’s descent, so I chose two people who I really liked, but who, for circumstantial reasons, I probably wasn’t going to get too deep with. (More broadly — and this is going to sound weird given that I now talk for a living — I’ve always been very self-conscious about talking too much about myself and my problems, which feels selfish. I’m actually a bit of a jerk about this: I think I’m a bit too quick to notice other people doing it, and I always judge them too harshly when I do.)

The fourth and final reason I didn’t really address my mental health in my twenties and thirties is a little bit embarrassing: Because I’m pretty fixated on the idea that I’m very lucky and privileged, I think I often said to myself, “Other people have it so much worse!” and may have used this as an excuse not to seek help. (I did a version of this earlier in this piece! But there I think it made sense.)

I’ve always been very cognizant of the insane material comfort I’ve benefited from, and I really do think that luck dominates the question of who gets what. So it was all too easy to say, “Okay, I’m often sad without knowing why, or knowing what to do about it, but look at how lucky I am to be alive in this time and place!” Plus, as I mentioned above, from my late twenties on I could compare myself to my mom and see that she clearly had it way worse. Who was I to complain?

I find this to be an interesting flip side to a problem folks like Jon Haidt have noticed: They think that one of the reasons social media has a negative impact on some people’s mental health is that it sparks so many maladaptive social comparisons. If you’re an insecure 14-year-old girl struggling with mental illness, and you’re mainlining Instagram, where all your friends publish extremely curated versions of their lives in which they are always with hot boyfriends and never have a pimple or a bad hair day, you might come to compare yourself obsessively to them, and you might find that you always come up wanting.

But the same thing can happen in the other direction! It’s not healthy, when you’re feeling down, to compare yourself obsessively to others — your mom, your one really messed-up friend from college, hypothetical starving Africans — and fixate on how good you have it. It’s just the same problem in the other direction, and I think it was a bit of a roadblock for me.

So there were a lot of reasons I didn’t get help in my twenties or most of my thirties. I let my issues fester.

***

Then the pandemic happened. Then my mom got sick. Then my mom died. Then my grandma died. Then my other grandma died. It has all happened very fast, and I’ve barely had a chance to process the full flood of it all. I don’t think this is unusual in the wake of a major loss, but I didn’t even really feel my mom’s death until perhaps six months after. And when the full flood did come, it felt like I was relying on a psychic foundation that had missed many years’ worth of inspections and been feasted upon by termites or something.

Hedge Monster: Okay, but you’re acting like there’s some good way to deal with grief, and like you’re sure what happened to you, and what you’re feeling, constitutes a particularly bad experience with grief. It could just be that this is what grief is, and that no amount of talk therapy or lavender-hued CBT books or woowoo vinyasa full-body breathing whatever spiritual tourism would have made your present situation any different.

That’s certainly a possibility, Hedge Monster, but I feel pretty strongly that it’s wrong. Because the grief has been worsened by all the same problems I’ve always had: my tendency toward endlessly circular rumination, my existential streak, my inability to compartmentalize in a healthy way and spend some hours away from dark facts over which I cannot hope to exert any control.

I think I screwed up, is what it comes down to. I think I missed an opportunity to buttress myself against stuff I knew was coming. And now I am walking around with pretty severe brain fog, and an inability to focus on my work (this is my first post in a week and a half — it was the holidays, but still!), and things do feel worse than they have to. I can’t prove it but that’s how it feels.

But I’m committed to improving the situation, even if it will be difficult. I don’t have control over all the stuff that’s stressing me out, but I have some control over how I respond. For one thing, I’ve gotten a lot better about talking to my friends about what I’ve been going through.

Everything was catastrophic in September 2020, when I emailed a group of them to tell them my mom had just been diagnosed with cancer. But there was a slight silver lining: I realized, looking at the list of email addresses, that I was really lucky to have them in my life. I’d known everyone on it for at least nine years, and I’d shared a roof, in one context or another, with all but one of them (I think the only exception was the husband of my friend, who I now consider a friend). But I don’t think I had previously talked to any of them about my mom’s depression, except maybe, in a couple of isolated instances, in an oblique and fleeting manner. So I disclosed it in the cancer email. And after explaining that I might simply ask them to talk or go for a walk with me as the situation with my mom unfolded, I added: “I’m not really good at asking for help in this manner, and that’s part of the reason almost no one in my life knows about the depressed-mom thing.”

You’re really robbing yourself of something vital if you can’t have honest conversations with your friends about your struggles. I’ve improved a lot in this area. When I was last in Boston, I had dinner with a couple I really like and who I’ve become friends with recently, and I opened up to them about what I was going through. They were characteristically empathetic. The husband, whose mental health struggles seriously dwarf my own, mentioned that he used to hate meditation because he couldn’t sit still even for five minutes, but he stuck with Sam Harris’s meditation app, Waking Up, and now he can meditate for an hour at a time, and he thinks it really helps his mental health

I’m supposed to be a Science Bro who looks askance at anecdotal evidence, but the fact was that sitting across the table from this guy who I really respect, and who has been through some shit, and hearing that he started in the same place as me — can’t sit still for five minutes to do the introductory meditations — and now he views it as a really important practice... well, maybe this is irrational, but that lit something in me that no randomized controlled trial could. I reactivated my dormant Waking Up membership this week. And I realized you can have exchanges like that only if you’re willing to open up to people about what you’re going through.

Other little things that hopefully will be big, or at least medium, in the aggregate: I got an in-person therapist. It was time. I’d been seeing someone remotely since the fall — I started seeing her for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, but as things got worse she just became my regular therapist (I do still need to address my insomnia) — but for whatever reason I respond more to in-person therapy, I think. I also joined a gym. I always get at least some exercise because I walk so much, but in the winter, when it’s too cold to run in the park, this will help me to get some serious cardio almost every day.

I’ve also been reminded that writing helps. Not just writing about all this, but writing in general. Last week I accomplished very little, writing-wise. I just couldn’t. It sucked. No focus at all, even by my own unimpressive standards. Over the weekend something shifted a little and I was able to write thousands of words — this post and most of two others. Just that act of having to organize my thoughts, of building something from nothing on a blank Google Docs page… it helps a little. Or at least it’s a distraction for a couple hours, and not the sort of distraction that makes me feel crappy and twitchy and unproductive (I’m looking at you, Slay the Spire).

I think the most important thing to realize is that there isn’t a simple dose-response relationship between what we experience and how we feel. There’s the question of what will happen to me in 2023, and there’s the question of how psychologically healthy I will feel in 2023. I have very little control over the former, and truth be told, there are some good reasons to think my external circumstances will get worse before they get better. But I’ve come to believe that on the latter question, I do have some control. And I really need to own that.

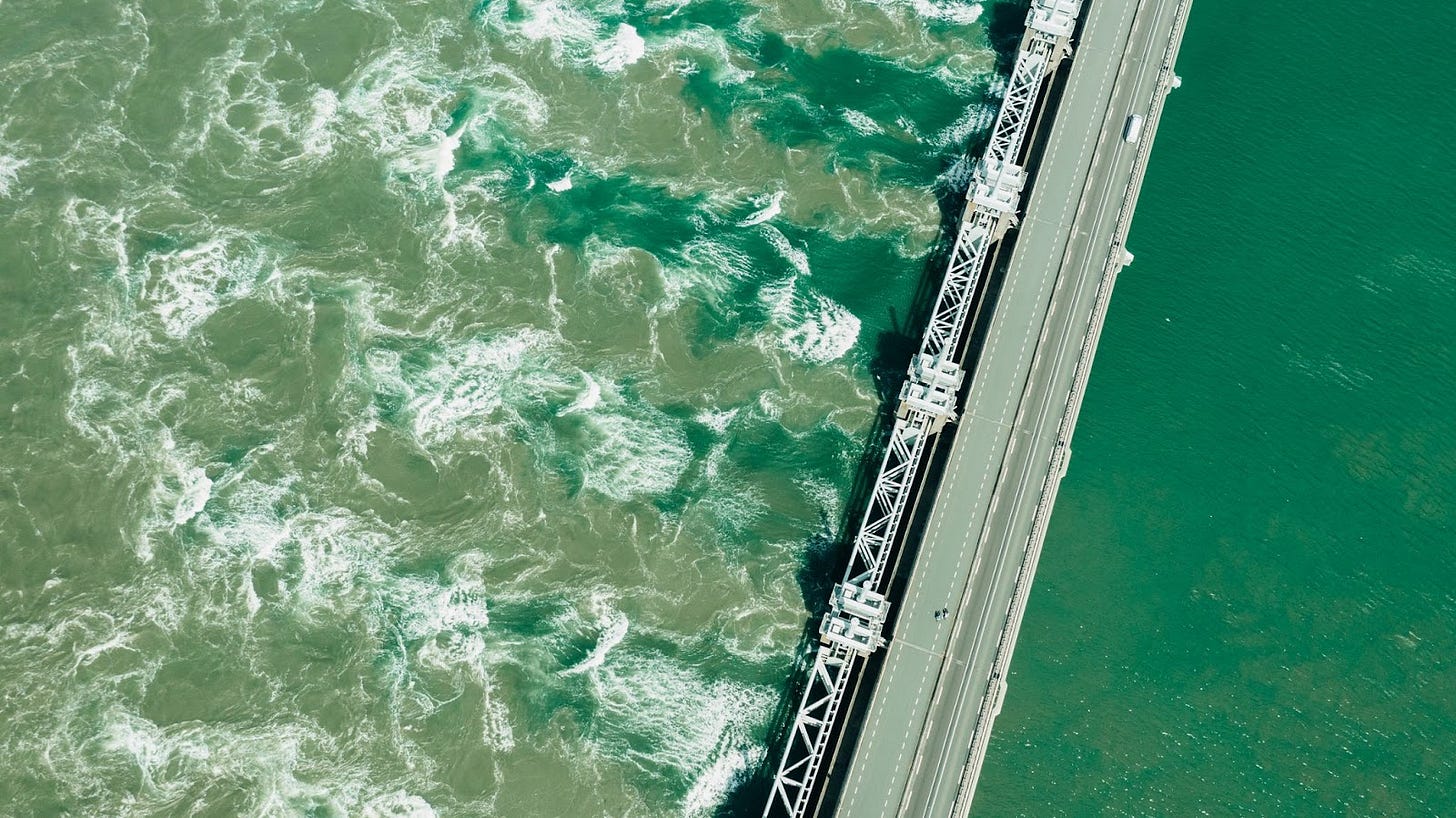

Questions? Comments? Stuff that has worked for you? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Image: “Oosterschelde flood barrier - stock photo” via Getty.

It isn’t very deep or groundbreaking, but I’ve given this out as a gift a few times and I’m glad I have a copy around. I also hate self-help and pop psych, so I’m extremely choosy about it.

Managing Your Mind: The Mental Fitness Guide https://a.co/d/ehQ81gI

What I've been gradually realizing with respect to guilt over "but most other humans have it clearly worse than I" is that it can't be about absolute standards, especially not simply material standards. If going by those metrics, then yes, we as non-impoverished developed country denizens in the 21st century are remarkably affluent and even privileged.

However, the human brain fundamentally works from relative standards, based both on what we observe immediately around us and perhaps most importantly, relative to what we were accustomed to earlier in life.

If there's a substantial downshift in circumstances e.g. deaths of multiple close loved ones in short order, or burnout, or divorce, et al. then there's a big delta between what you knew for the longest time versus now. That's what really matters in the end, as far as "permission" to acknowledge that we're struggling is concerned. On a purely neurological level, the amount of anxiety/suffering/depression etc. really can be identical to what's experienced by a mom in eastern Ukraine fearing for the safety of her family, or the child in rural Ethiopia who has no idea where dinner will come from or it will be a thing at all, or the guy who had his entire family slaughtered in a shooting.

In terms of getting help, better late than never. This was a timely post for me as well, so thank you for breaking out of your shell and sharing.