The News

A year ago today today my dad called me right as I was getting to the northwestern tip of Prospect Park for a run. “I have some bad news about Mom,” he said. More bad news is what he meant. My mom, Sydney Altman, had recently entered an in-patient facility because her depression had reached such a dangerous new low. Not the first time that had happened.

But then it turned out that in addition to having psychically eviscerating, treatment-resistant depression, she also had Stage IV cancer that had spread to her brain. It maybe helped explain why her speech had slowed recently (which can also be a symptom of severe depression).

I mumbled something like “Thanks for letting me know — I love you.” And did my run. It didn’t make sense to do anything but my run. I had come to the park to run, after all. I must have been in shock.

The Promise

Some weeks later, I watch a very successful middle-aged doctor — well-put-together, exuding competence and confidence — lean over my mom, who checked into a depression ward and is now all of a sudden in an oncology ward, and wrap up his appointment with her by saying something very close to, “We are going to get you better.”

Fuck you, I think to myself. Seriously, fuck you — you have no way of knowing that. We haven’t even done the sequencing yet! Why would he possibly say something like that?

The Sequencing

Genetics has led to a revolution in cancer treatment. Well, some cancer treatments. It turned out my mom had non-small-cell adenocarcinoma. This is the ‘best’ type of Stage IV lung cancer to have — or so we were told — in the same sense that if your choice is getting chased by a ravenous grizzly bear in an open field or chased by a ravenous shark in open waters, the grizzly bear is the ‘best’ choice.

What they do is get some of the cancer tissue and sequence it and they tell you your options. ‘EGFR’ is a very good mutation to have. If you have it, your cancer will likely respond to pills known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or TKIs. These drugs tend to be much more effective, and to have far fewer and less severe side effects, than older approaches to fighting Stage IV cancer like traditional chemotherapy or radiation. (Because Stage IV means the cancer has spread widely, it isn’t generally considered curable — Stage IV cancers can’t typically be blasted to smithereens with radiation or simply cut out of healthy tissue the way some earlier-stage cancers can, though it’s worth noting that even those cancers can come roaring back later on, long after their apparent defeat. And once in awhile someone with a Stage IV diagnosis does get very fortunate and is effectively ‘cured’ of any detectable signs of cancer.)

Problem is, this is one of those areas where being white is a bad thing — caucasians with cancer are much less likely to have this mutation than Asians, for whom it’s about a coin flip. If you’re white and have lung cancer, you have maybe a 15% chance of having an EGFR mutation, though the figure varies from study to study.

So my mom was unlikely to have it. But there was still, technically, some hope.

The Family

When a catastrophe hits a family, certain interfamilial dynamics and individual personality differences become a lot more apparent. My dad, for example, is a much more optimistic and less neurotic person than me. This is broadly true of the overall Singals-versus-Altmans divide, and when it comes to these sorts of traits I am far more Altman than Singal. Less optimistic and less psychologically healthy, I mean.

So he explained the general situation to his three sons with a trace of brightness. Once the results of the sequencing were in, we’d know which treatment option Mom had: Either traditional chemotherapy, or a pill, or immunotherapy (via infusion), or maybe some sort of combination. But no matter what there would be some option.

But I knew this was only sort of true. Not long after learning of the diagnosis I had looked up five-year survival stats for my mom’s cancer (not good). It’s just who I am; I can’t help it. So I also knew that if the dice came up CHEMO, that wasn’t really an ‘option’ in the sense the other two were options. The studies I could get hold of about chemo for late-stage cancer showed very slim benefits and lots of nightmarish side effects. A society that talked about end-of-life care more honestly than ours would probably also talk about chemo more honestly, meaning whether it’s even worth deploying it in many Stage-IV contexts. (There are miracle stories, and some people don’t have serious side effects — I’m talking averages here and certainly not saying people shouldn’t have the option of going on chemo even in dire situations.)

I don’t think my dad or the rest of my family knew this, because they didn’t do what I had done and immediately jump into a grim tangle of data. We’re all different. It’s probably best, during a catastrophe, to have some diversity of personality within a given family: optimists and pessimists and those in the middle. I shudder to think how much worse this all would have been if the rest of my family were very similar to me, especially my thankfully-very-different dad.

Anyway, I kept quiet, but I knew that my mom wouldn’t live very long if the only option was chemo.

The Walks

My mom got her biopsy and came home before the results arrived. She was in bed most of the time — on top of everything else, since the cancer demanded everyone’s attention, there wasn’t really much of a chance to aggressively treat the depression that had landed her in the hospital in the first place — and I started shuttling back and forth between suburban Boston and Brooklyn. Both my mom and dad wanted me to maintain a semblance of a normal life, so I tried to strike a balance. Approximately two weeks there, two weeks here in Brooklyn, back and forth on that mostly boring and frequently traffic-choked interstate drive.

When I was home I went on a lot of walks. I mean, I always go on a lot of walks, but a lot of walks. More frequent and longer than usual. I had a couple of routes that wound through the pleasant leafy suburban streets of my hometown. Lots of hills. In recent years I’ve come to fully appreciate a nearby nature preserve that is — according to a massive number of lawn signs at least — apparently threatened by that ever-expanding beast to the northeast, Boston College. The school wants to pave over nature to build ever bigger and fancier facilities to compete for the brightest and wealthiest kids possible. Or something like that.

It was during one of these walks that I came closer than I ever will, I hope, to understanding what it was like to be my mom. Because (again) of who I am, early in my mom’s illness I became fixated on the idea that amidst this disaster centered on my mom, my dad would just up and die on us, likely in the middle of the night. It would just be me and my brothers alone with our profoundly depressed and cancer-ridden mom, no Dad to keep everything on the rails.

Intellectually I knew this was pretty unlikely, but somatically, in the middle of the night, it felt like a distinct possibility, if not an imminent one. One night I got almost no sleep because I was so scared about this, and then the next day, a complete wreck, I tried to go on my normal walk, hoping it would make me feel better.

I entered a strange and scary state that day. The heaviness. People revert to that cliche about depression because it’s true. It felt as though I had strapped a bunch of weights to my legs and torso and arms. Like I was dragging a mostly-dead mound of flesh miles and miles and miles. It was so, so difficult. Like nothing I’d ever experienced, even during my own psychological low points.

Then, the talking thing: I went into a Dunkin and tried to get an iced coffee. Talking was a fraught tightrope act, because if I spoke more than a few words without pausing and breathing, it felt like I was going to start sobbing uncontrollably. Right there in the Dunkin. I had to be very careful because I didn’t want to make a scene, getting my mask soaked and all that. I must have sounded like: Could I please… have a… medium iced coffee… with… Like someone whose first language wasn’t English.

It was a surreal, viscerally distressing day. I was also grateful for it. I really think it was a close facsimile of what people with major depression experience. Except I got to go home and get some sleep and feel more or less like myself the next day. If you have severe and treatment-resistant depression, that just is your life, and often for months or years on end. Or forever. That’s what my mom went through. It’s unfathomable — I feel like I would just give up so quickly. She dealt with that for a decade, off and on.

The Results

Later in September, a phone call: Our first good news since the catastrophe started. Mom was EGFR-positive. Holy shit. She can take pills that will have mild side effects, and those pills are likely to shrink and/or slow or stop the growth of the tumors. Third-generation TKIs even do a good job of crossing the blood-brain barrier: They could shrink my mom’s brain metastases. There are a fair number of said metastases but they are very small, we are told, and they probably can’t explain her speech issues and other worsening cognition problems.

Hugs and a dive back into the literature. I learn a bunch of new terms like ‘PFS,’ or “progression-free survival”: how long, median-wise, a drug grants someone a reprieve from their cancer growing. So if people enjoy a median PFS of 10 months on a drug, that means that when they take it, they are likely to have about 10 months during which their cancer doesn’t get worse. With TKIs, almost inevitably, the cancer mutates and the drug stops working. When the scans reveal ‘progression,’ you might be able to try another drug, or maybe another targetable mutation will pop up. Or it’s time to move on to chemo, which is for many people the final treatment they try before hospice.

In all these cases, Results Not Guaranteed. Huge variation from patient to patient — your PFS might be zero months (if your cancer doesn’t respond to the drug at all, which can happen even if you have the right mutation) or it might be 36. I read about outlying cases where people on my mom’s drug, Tagrisso (osimertinib), lived for years and years — I would get visceral jolts of happiness thinking about that. I would pore over statistical tables trying to figure out what we knew for sure. But these are pretty new drugs and the answer was “not a whole lot.” I settled on what felt like a safe assumption: my mom’s estimated PFS on Tagrisso was about 18 months, and her estimated overall survival was perhaps two or three years.

Catastrophes reorder expectations so quickly. In August, if you had told me my mom would be dead in three years, I would have been disconsolate; in September, it felt like such a long time. Plus, they are always coming up with new drugs, and the fourth-generation TKIs — meaning drugs that might offer significant hope after Tagrisso stops working — are on the horizon. So if you can stay alive three years, a lot can happen. You hop from drug to drug, trying to stay dry as the waters rise inexorably. Some people can — have — pulled this off for many years.

But it depends, it depends, it depends.

The Response

We were happy about the news but it seemed to just glance right off my mom, barely denting her depression. Which makes perfect sense: She was in a cartoonishly bad situation. She was going to die pretty soon. Along the way, this woman — this depressed, anxious woman — would be subjected to brain and body scans every six weeks or so. Damocles.

The first one was good — significant reduction of the primary and metastatic tumors. Hardly any brain metastases left. But she still had a lot of cancer and it wasn’t going anywhere. The first set of scans often look good, but that reduction is the best you are going to get in many cases; from then on, the doctors view it as a victory if the cancer doesn’t grow. They aren’t even looking for more shrinkage, not realistically. (Again, there are exceptions and miracle cases.)

And think about my mom’s situation. Really think about it: You already have treatment-resistant depression, and then you have Stage IV cancer, and now the best-case scenario after receiving these scans, which cause you tremendous anxiety, is to be told, “Well, you still have a lot of cancer, but it doesn’t appear to be growing, for now. Mazel tov! Remember that eventually it will grow and kill you. See you in six weeks.”

I don’t want to downplay the importance of these drugs. They’re amazing. They do add years to some people’s lives, and years are very important. They’re all we really have. But in retrospect, it was unfair of us to expect my mom to get much happier because of the mutation. I felt guilty she didn’t feel happier, she felt guilty she wasn’t happier despite the glimmers of light she sensed in her husband and sons — there was just a lot of guilt. And there would be more.

The Commercials

The time I spent with my mom when she was sick, I was often next to her in her and my dad’s bed. Usually the TV was on. It turns out there are a lot of commercials about cutting-edge cancer drugs. The ones we saw all tended to follow the same format: There’d be soft-lit, gentle scenes of older couples — impeccably groomed, in impossibly good shape — enjoying dinner parties and walks on the beach and bonfires, often surrounded by joyous kids and grandkids. Phrases like More Time were the norm. I appreciated that — there was honesty in it and it’s good for people to understand what a Stage IV cancer diagnosis usually means. More time, not a cure.

In theory, yes, Tagrisso (and Tarceva (erlotinib) and Sprycel (dasatinib) and so on) did allow some people to go on walks on the beach and attend dinner parties and enjoy spending time with their grandkids. For a long time, in some cases.

Not my mom, though. She was too depressed. She didn’t really enjoy anything. She didn’t want to eat. It was getting harder and harder for her to even get out of bed, and harder and harder for me to spend time with her there. I started resenting the commercials. I was jealous of the fictional family members who got to enjoy relaxing dinner parties with their parents, who were dying so slowly and so vivaciously.

The Guilt

At some point I want to carefully work through my behavior between September 3, 2020 and April 20, 2021. I mentioned this on the podcast, during the only other time I’ve said anything publicly about the past year: I feel guilty I didn’t spend enough time with my mom while I could have. Even when I was home, I often was going for long walks or seeing friends or even just watching TV upstairs in the attic, away from her.

Now, she was only rarely left alone. My dad was working from home during this period, and if he had a Zoom meeting in the other room or something, I would make sure to “fill in” for him next to my mom. When I was home, we (and my other brothers) would talk about our schedules and make sure someone was with her as much as possible. But it was really hard to be with her: It was like with the end approaching she was finding it harder and harder to contain what felt, to her, like a lifetime of disappointments and resentments and traumas.

In one sense, she was operating from a distorted vantage point: She’d only been really depressed for a decade or so, and prior to that had had a busy, high-functioning life. But here she was, at the beginning of her end, and it’s understandable, especially in light of her overall mental state, why her depressive ruminating was spiraling out of control and inflicting some collateral damage on those closest to her.

A lot of it was out loud. It was hard to hear. She lashed out angrily at me once in a way I found deeply unfair and wounding. There was a lot of resistance to my attempts to get her out of bed and onto her feet — I don’t know a lot about medicine but I do know that being in bed 23 hours a day is terrible for you and will exacerbate any health problems you have. I’m sure I was sometimes curt or even a little bit cruel, that I violated my firmly-held belief that it’s bad to tell depressed people anything in the same galaxy as Cheer up or Look on the bright side! At one point I remember basically explaining to her that we all wanted her to stay alive for a long time, and were to a certain extent changing our lives to try to help her, but we couldn’t make her want to be alive.

Her memory got worse and worse — we still don’t know why but there was nothing in her brain scans to explain the decline. It would be Tuesday and I’d have already told her and my dad I was driving back to Brooklyn Friday, but she would convince herself that actually, I was leaving the very next day, and tell me how sad she was about that, her voice quivering with anxiety. I’d say Nono, Mom, I’m leaving Friday. She’d be reassured. Then, an hour later, she’d forget that she’d been reassured and revert to thinking my departure was imminent.

So it was not easy to spend time with her. So I didn’t maximize my time with her. And I have such a fuzzy sense of whether this was wrong, or exactly what my obligations were. The fact is that when it comes to family members with whom we have complicated relationships — especially those suffering from serious mental-health problems — we make our own decisions and set our own boundaries all the time. There’s no rulebook. I definitely could have spent more time with her, though.

The Context

My assumption all along was that we were only at the very beginning of the end and that, since she had responded to the Tagrisso, she’d almost certainly be alive in a year and most likely significantly longer than that, that there’d be a clearly-signposted end of the end, likely involving either chemo or a joint decision with her not to bother, and there would be time to have the real end-of-life conversations her present state — and my avoidance — was preventing us from having, that everything I was doing was justifiable because she was still very alive and we had time, we had time, we had time...

The Emails

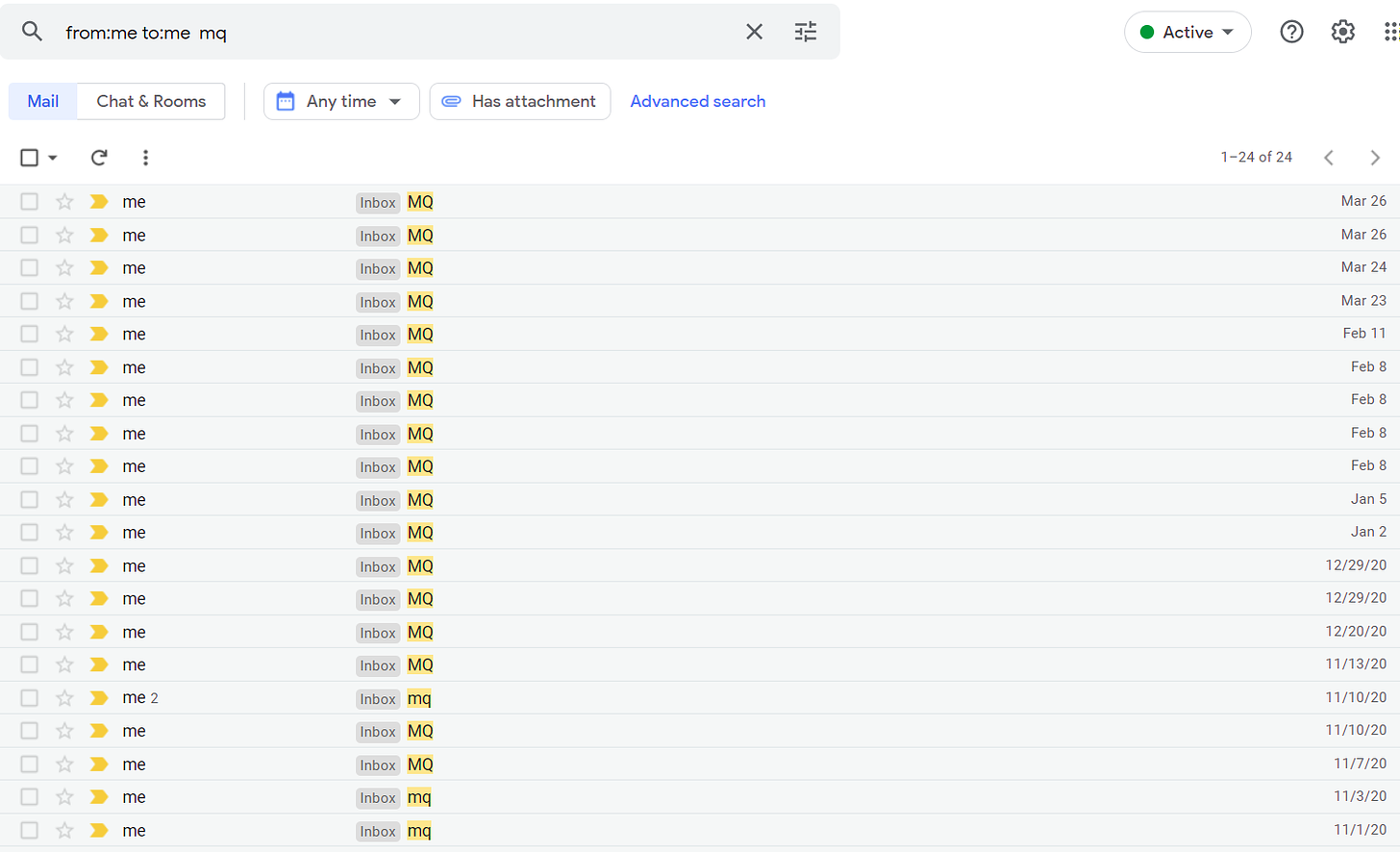

When my mom said something about her situation that I wanted to remember, I would whip out my phone and punch it in and send it to myself with the search-friendly subject line ‘MQ,’ for “mom quote.”

I have 25 of these emails, and they range from November 1, 2020 to March 26, 2021. They are not easy to read but I am very glad I have them.

The Cliff

My mom’s mental and physical health nosedived in February and she had to go to the hospital. It wasn’t even the cancer, which appeared to still be under control — at least not directly.

Here’s where the slight fog of “Should I have spent more time with her and less walking?” gets much more extreme. Where moral visibility drops to zero. There were a lot of covid problems and a lot of visitor restrictions. I actually went back to New York not long after she was admitted, because I couldn’t visit her — my dad was the only one allowed to. Then I went skiing for a few days in Maine, because I couldn’t visit her. What else was I supposed to do? I couldn’t visit her. I needed the distraction.

Except: Could I have visited her? Really, Jesse? There was nothing you could have done? The fact is I didn’t try that hard. The night in February when things got so bad we had no choice but to call an ambulance in the morning was one of the worst nights I will ever experience, I hope. I think I just wanted a break from this whole depressed-mom-with-cancer thing. I feel horrible about that, but that’s my honest explanation for my behavior. It had been nothing but failure and decay and heartbreak, the stupid EGFR distraction a complete nothing, a cruel trick. I’m not saying I definitely could have visited my mom, but I definitely could have tried harder.

The Return

Eventually I did get back and could visit my mom in the hospital and she only sort of recognized me. She was a different person than the one I left behind when I was last in Massachusetts. She effectively had severe dementia. A lot of people live through watching a parent decline over the course of five or ten years — this was all compressed into just a couple months.

None of the doctors understood exactly what had happened. The cancer was under control, technically, but had clearly set off some sort of chain reaction that was wrecking her body and her mind. They eventually told us that they were concerned that the ongoing stress of being in the hospital was causing harm, and that they couldn’t honestly say it was outweighed by any tangible medical good they were delivering. They had sort of run out of ideas. They convinced us it was time for home hospice.

We took her home and we hired some nursing help and we waited for her to die. Friends and family came from near and far and held her hand and tried to talk to her but mostly talked about her, sharing memories, and every day she was a little bit less responsive. People wouldn’t stop sending us pastries and pasta and bagels and I still haven’t lost the weight.

The nurses we hired, like so many of the other medical personnel we interacted with, were absolutely heroic. At a time when things were really bad, we started talking to one overnight nurse, an immigrant from Kenya. She proudly showed us photos of her son, who was set to start attending, and playing football at, an Ivy League school.

I needed to hear that story so badly.

The Delusions

As the catastrophe washed over us, my mind performed a monthslong gymnastics routine. It twirled and leaped and somersaulted trying to convince itself that what was happening wasn’t happening. This didn’t manifest as outward denial, but rather as it’s-not-so-bad-ism. First it was something like, Well, after she dies I’ll interview a bunch of her friends and family and sort of rebuild her life so that we don’t have to focus so much on this last decade. Then something like, I bet it won’t hurt that bad when she dies since I haven’t been as close to her lately since her mental health has been so poor and I’ve felt so helpless about it. Then, When she dies, it will actually be a little bit of a relief because what could be worse than these last few months?

I’m not proud of these thoughts but this was what my mind was doing rather than staring the monster right in the face, because that’s impossible to do. Instead, there was a whole elaborate distracting performance. Imagine someone forced to dance for hours, their exhaustion and soreness evident to the tiring audience, the routine becoming ever less impressive and captivating and convincing.

The End

We were right there in the room with her when she died in April. We had that, at least. It’s better than many of the alternatives. We were lucky in certain regards.

The Memories

I’ll often remember some random moment from my recent past — say, within the last five years — and find it absolutely unfathomable that during that period, I wasn’t thinking thoughts like, Huh, my mom’s alive — I should really take advantage of that! Or maybe, It’s awesome having two parents who are alive; this situation is great.

Of course we don’t do that. Whatever good fortune we have we inevitably take for granted. I really, really, really wish I had made more of an effort to understand my mom and her suffering back when I could have.

The Future

I’m okay. I’m fine. It’s fine. Tonight I’m getting dinner with a high-school friend and tomorrow there’s a birthday party at a big outdoor bar. I am not in bed all day crying and I am fulfilling the responsibilities I need to fulfill. I’m lucky I don’t have what my mom had in terms of genetics and my mental health. But what happened to her is so unfair and it hurt us all so badly. I don’t have anything more sophisticated or deep than that to say. And I’d resisted writing anything about this for months. It just felt like time.

I wish I had a more satisfying conclusion than that. All I can really say is: If you have something that feels potentially addressable lingering over your relationship with someone you love, address it while you can.

And I hope anyone going through anything remotely like this gets the help they need and feels comfortable talking about it honestly — even if that’s uncomfortable. It should be uncomfortable.

The photo is from my mom’s obituary.

Your podcast about this prompted me to talk about end-of-life care with my own parents, and gave me insight into what my mom must have gone through a few years ago when her parents' health declined before passing away. Your empathetic and honest words about the ugly parts of having to say goodbye to a parent are really impactful. Thank you for sharing such raw parts of your experience. I'm sorry for your loss, and hope you are kind to yourself and forgive yourself of any lingering guilt. It's hard to believe the empathy and love for your mother present in this writing wasn't obvious to her in the time you spent together.

Jesse: I am so sorry to hear about your family’s suffering and your tremendous loss. I cried while reading this piece. Thank you for sharing your experience. It’s a moving set of thoughts. I’ll return to this one day.

“I started resenting the commercials.”

Good grief. For the last 9-10 months, a family member has had some symptoms that may be [not including the name of a specific condition that’s really bad]. And we’ve been getting these weird commercials that are basically trying to sell us stuff related to treating and testing for that condition as well as some food the family member has been eating in order to deal with some of the symptoms. Bizarre, right? Well, I’m almost certain these ads are targeted at our home, given web searches we’ve done (TV and internet are provided by the same company). This is surveillance capitalism.