Adam Grant vs. Coleman Hughes, Part 2: Causation Does Not Imply. . . Anything

The sequel all of America has been eagerly anticipating, by which I mean perhaps 3% of my readers

This is the long-overdue Part 2 of my October 19 post, “Is There ‘An Extensive Body Of Rigorous Research’ Undermining The Case For Color Blindness, As Adam Grant Claimed?” This one sort of stands on its own, but you’ll be missing a lot of context if you haven’t read Part 1.

My 2021 book, The Quick Fix: Why Fad Psychology Can’t Cure Our Social Ills, centers largely on a basic thesis about how the results of psychological research, social psychological research in particular, are marketed to the public. This thesis is relevant to the disagreement between Coleman Hughes, Grant, and me:

Within psychology, particularly social psychology, [certain] tendencies have given rise to what I call Primeworld, a worldview fixated on the idea that people’s behavior is largely driven—and can be altered—by subtle forces. Central to Primeworld is [sic!], well, “primes,” the unconscious influences that, according to some psychologists, affect our behavior in surprisingly powerful ways: holding a warm drink makes people act more warmly toward others, claims one finding, and being exposed to stimuli connected to the elderly makes people walk slower, claims another. The proponents of Primeworld suggest we can work toward “fixing” individuals by helping them to understand the influence of primes and biases. Their accounts have three main characteristics: big, imposing social structures and systems are invisible, unimportant, or improved fairly easily; primes and biases have an outsize influence on societal outcomes; and these primes and biases can be fixed, to tremendously salubrious effect, thanks to the interventions offered by wise behavioral scientists.

This worldview treats complicated problems as though they can be significantly ameliorated or solved with quick fixes: with cute, cost-effective interventions by psychologists. Over and over, throughout this book, we will see situations in which otherwise brilliant researchers examining some of the most complicated problems known to humankind have adopted the tenets of Primeworld. Whereas a social scientist taking a broader view might look at a problem like “the education gap” between white and black students and explain that it has many complicated causes, ranging from segregated schools to early-life experiences to the impact of tutoring, Primeworld adherents will take a different tack. They will stress that a great deal of progress can be made by optimizing the individual participants in the system, whether students (perhaps via increasing their “grit,” meaning their ability to stick with difficult problems tenaciously) or teachers (perhaps via IAT-based trainings). [footnotes omitted]

“Primeworld,” uh, didn’t exactly catch on, but I still think my overall diagnosis was accurate. And this worldview, that humans can be tweaked in salutary ways without much effort, is fueled in large part by cute and attention-getting social psychology experiments. For a variety of reasons, many of which I cover in my book, it is — or at least was1 — very easy for psychologists to generate exciting-seeming results in experimental settings. Take a bunch of undergrads, expose half of them to some intervention and the other half to some control stimulus, compare the differences, and boom: THIS ONE TRICK CAN CURE DEMENTIA, and then the trick is, like, staring really hard at a photo of an MRI of a human brain for 30 seconds.

Okay, that’s a slight exaggeration. But especially during the period covered in my book (2010-ish), a lot of the claims made by big-time psychologists really did get out of hand. And then, when other scientists tried to replicate some of these exciting experiments, they weren’t able to.

As I noted, the specialty of social priming, or the idea that subtle stimuli can have significant effects on human belief and behavior, produced a lot of sexy results, but fared particularly poorly, replication-wise. As did social psychology, the broader subfield of psychology which birthed social priming:

It doesn’t appear anyone has quantified the replicability of social-priming research compared with other types of research, but the outlook appears to be abysmal. [Replication and transparency in psychology maven Brian] Nosek is a careful, measured speaker when he talks with the media, and yet here’s what he said to Nature’s Tom Chivers about social priming in 2019: “I don’t know a replicable finding. It’s not that there isn’t one, but I can’t name it.” In a May 2020 email Nosek confirmed he wasn’t aware of any attempt to track the specific replicability of social priming. But for what it’s worth, social psychology, the home base of social priming, fared particularly poorly in the original Many Labs [replication] effort: “Combining across journals, 14 of 55 (25%) of social psychology effects replicated,” which was worse than the already-dire rate observed in other areas of psychology. [citations omitted]

Social priming was one of the worst offenders, but really, all the popular and sexy forms of experimental psychology were affected. So what I’m getting at is that we shouldn’t give public-facing experimental psychology the benefit of the doubt; rather, our default stance should be skepticism.

But Adam Grant, the superstar organizational psychologist who was one of the main characters in Part 1, is also worried about undue skepticism of psychological findings. During my back and forth with him in October, he sent me an email which read, in part:

I think an unintended consequence of the replication crisis is that critics often approach a body of research like prosecutors seeking a conviction. That makes it easy to discount arguments based on the weakest evidence. (I know from experience—a colleague once warned me that I was at risk of becoming a “professional debunker” thanks to my tendency to flip into prosecutor mode when I think someone is preaching based on flawed data or a one-sided argument.)

He added that “When we look at the same literature through the lens of a scientist or journalist pursuing the truth, we wind up paying more attention to the patterns across the strongest evidence.”

I have to admit that I got a little bit miffed by this.

Generally speaking, psychologists in the TED Talk world of sexy translation and application have not racked up an impressive track record when it comes to producing durable theories and interventions. In recent years, some of the most popular and well-known experimental psychologists have produced heaps upon heaps of research that may turn out to have a net negative effect on science and on the world. I’m saying this not to be unnecessarily provocative but to describe the stakes accurately: if you publish a study and overhype it before the evidence is truly in, and as a result excitement, further research, and real-world interventions are generated, and then your finding turns out not to hold up to rigorous replication attempts, you have wasted a huge amount of people’s time, money, and other resources. This has happened over and over and over again.

Of course, it isn’t just the stars whose work fails to replicate: plenty of less renowned studies by less renowned scholars have also been toppled. Overall, I’m having trouble coming up with any reasonable counter to what I will admit is a rather strong-sounding argument: there is no prima facie reason to believe any given published psychology study reflects important real-world phenomena, particularly when it comes to studies that 1) were published before the present wave of concern over quality control, 2) lack certain quality-control guardrails against questionable research practices (QRPs), 3) deal with small and/or nonrepresentative samples, and 4) concern highly politicized issues (more on this at the end of the post).

If you read Part 1 you’ll recall that Grant did not exhibit much of this caution when discussing the alleged case against color blindness. Rather, he touted a meta-analysis lead-authored by Lisa Leslie as constituting “an extensive body of rigorous research” highlighting the potential perils of color blindness, despite the fact that 77% of the included papers were correlational and therefore couldn’t really tell us much about what was causing what. Let’s set this aside, even if it isn’t actually set-aside-able. Because I think the remaining papers generally shouldn’t be trusted — they’re experimental, yes, but they’re exactly the sorts of wobbly findings I criticized in my book, and they tend to satisfy three or four of the above criteria. I think when it comes down to it, Grant is simply asking us to make the same mistake everyone’s been making all along, and to accept a bundle of weak experiments conducted in lab settings as moderate or strong evidence for a real-world effect. As Grant himself noted in our initial correspondence, “I strongly agree that we need to be cautious about extrapolating from stylized experiments, and that field studies and experiments with behavioral [dependent variables] are the most relevant. Even the higher-quality evidence doesn’t lend itself to obvious policy implications.” But that’s exactly what he did when he told Chris Anderson Hughes’ TED Talk lacked scientific validity: He over-extrapolated from stylized experiments.

Now of course there’s a sliver of truth to Grant’s argument, in that there are situations in which people’s skepticism tips over into irrationality, or is politically motivated (like the “merchants of doubt” within the scientific establishment who, their critics argue, make industry-friendly arguments about subjects like smoking and global warming). But I really don’t think that’s what’s going on here. We have strong evidence to believe that, depending on the subfield in question, a given experimental finding in psychology has maybe a coin flip’s shot at replicating. And that’s arguably generous when you’re talking about social psychology. We also have strong evidence to believe that even if a given lab experiment does replicate, there’s still a long way to go before anyone can say, with certainty, that the lab effect in question matters in real-world settings.

In the case of the experimental papers referenced by Grant and the meta-analysis, we’re being asked not only to assume, solely out of the goodness of our hearts, that the papers in question would replicate if subjected to that test, but also that we can safely generalize their findings to the much bigger, more complicated question — really about a thousand different questions, all very context-dependent — of whether and when and to what extent we should deploy color-blind ideas and ideals to fight racism and inequality. The fault lies with those who are promoting these sorts of claims about behavioral science, not with the skeptics!

But you needn’t take my word for it — we can simply pull up the experimental studies in this area and evaluate them on their merits. To make my point, I’m just going to focus on three of them: two which were included in the meta-analysis, and one which Grant presented to me as solid, generalizable evidence for the potential shortcomings of colorblind approaches to fighting racism. To be clear, I have not read each and every one of the experimental papers included in the meta-analysis. But I can just about assure you that if you take on that task in the search for carefully constructed and high-quality studies employing anti-QRP measures that offer strong or even moderate evidence on these questions, you will come up empty, or nearly empty. This is not quality research.

High-Conflict Situations In Psychology Labs

In their meta-analysis, Lisa Leslie and her colleagues include ten samples from an experimental study by Joshua Correll, Bernadette Park, and J. Allegra Smith called “Colorblind and Multicultural Prejudice Reduction Strategies in High-Conflict Situations,” published in 2008 in Group Processes & Intergroup Relations.

Your mileage may vary when it comes to the question of what a “high-conflict situation” is, because this is a study where the researchers asked college students to sit and think about maybe not getting to take a class they wanted to take. The use of college students is itself understandable — that’s what a lot of psychological research is. College students are cheap and plentiful, like cigarettes in states with low tobacco taxes. But what can we really learn from a study like this? How applicable is it to the real world? Can we comfortably bridge the gap from studies like this to the claim that there is “an extensive body of rigorous research” pointing toward or away from any proposed approach to generating salutary societal outcomes?

Here’s the abstract of the article:

We tested colorblind and multicultural prejudice-reduction strategies under conditions of low and high interethnic conflict. Replicating previous work, both strategies reduced prejudice when conflict was low. But when conflict was high, only the colorblind strategy reduced prejudice (Studies 1 and 2). Interestingly, this colorblind response seemed to reflect suppression. When prejudice was assessed more subtly (with implicit measures), colorblind participants demonstrated bias equivalent to multicultural participants (Study 2). And, after a delay, colorblind participants showed a rebound, demonstrating greater prejudice than their multicultural counterparts (Study 3). Similar effects were obtained when ideology was measured rather than manipulated (Study 4). We suggest that conflict challenges the tenets of a colorblind ideology (predicated on the absence of group differences) but not those of a multicultural ideology (which acknowledges difference).

You’ll notice that this particular article doesn’t even point in an anti–color blindness direction, at least not cleanly. But set that aside, because my point is you can’t use these studies to draw any zoomed-out conclusions of any sort.

Let’s take Study 1, which was interpreted by Lisa Leslie and her colleagues as demonstrating a small negative correlation between color blindness and stereotyping, and a small positive correlation between multiculturalism and stereotyping. In it, 117 white students in an introductory psychology course at the University of Colorado were “in partial completion of a course requirement,” “asked to read a paragraph describing the testimony of sociologists and political scientists who stressed the importance of either ignoring ethnic divisions and learning to see others simply as fellow human beings ([colorblindness]), or appreciating ethnic diversity and learning to see variation as an asset to society ([multiculturalism).” Then they were asked to write down some of the benefits of the approach they had read about. Members of a third control group “spent a comparable time thinking about ethnic relations in the USA and listing their thoughts.”

Then the students were assigned to randomly read one of two fake newspaper articles describing a proposal by a (nonexistent) Hispanic student group to alter the system by which students at the school registered for classes. The two were mostly identical, except in the “low-conflict” condition, the new proposal wouldn’t affect white students, while in the “high-conflict” condition, white students (and white students alone) might be given fewer slots in desirable courses.

Finally, among other responses, students were asked to rate different racial groups on a “warmth thermometer” from 0 (how I feel about Hamas) to 100 (how I feel about Tom Brady). They were also given eight so-called “Peabody sets,” which are too complicated to explain in an already-getting-bloated article, but which are a different way of measuring ostensible prejudice against various groups.

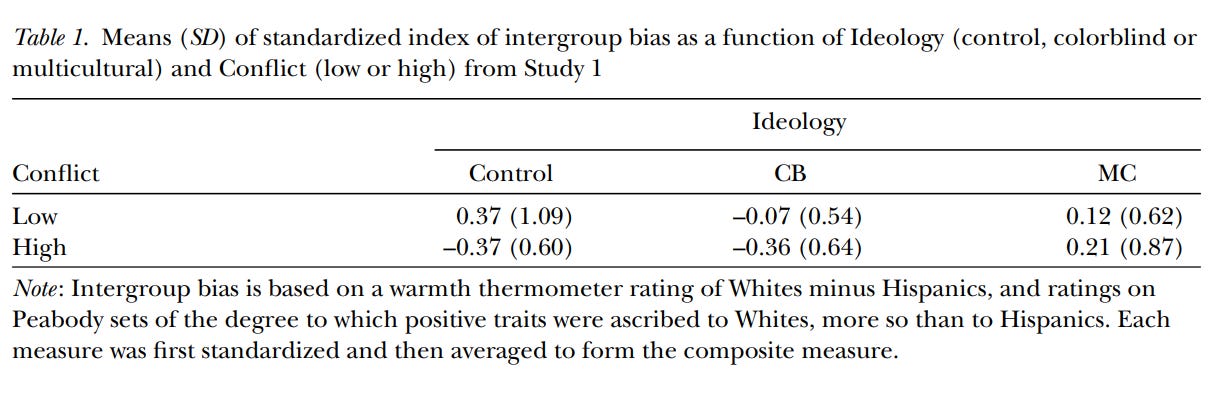

Among their other analyses, the authors “standardized and averaged the two scores” on these two bias measures, which were correlated, “to form an overall bias index.” This allowed them to more easily conduct various analyses measuring the effects of these different conditions on the students’ level of bias, generating these sorts of results (no worries if you don’t understand the table):

Now, the authors subsequently write that they don’t really believe the findings they got here — they expected kids in the high-conflict group to respond to the questions more racist-ly than those in the low-conflict group, which wasn’t what they found. The researchers argue that the kids probably were feeling racial resentment but trying to hide it, which is why they turned to the supposedly more honest and accurate (???????) implicit measures they employed in their later studies in this paper.

But none of that really matters for our purposes. What matters is: Do you think this sort of result tells us anything about society? Do you think forcing a psychology student to read a thing, and then think about it, and then read another thing, and then fill out a survey rating their feelings toward (say) black people from 0 to 100, tells us about which approaches to race and racism will help heal our fractured world? I don’t. This is an exceptionally contrived exercise. That’s not to say it has no value — maybe it does, if you’re using it to make certain very basic, humble points about how students in a lab setting react to certain stimuli. But the exercise these students were put through bears no resemblance to how the real world works, except in the most superficial sense. Even setting aside the very real possibility that this study wouldn’t replicate if a different team ran it again, it can’t be used as meaningful evidence for or against color blindness or multiculturalism or anything else in real-world settings.

It’s Not My Fault I Would Like Lamar More If He Were Into Hip-Hop — I Was Just Primed That Way

Here’s the abstract of the second study I want to discuss from the meta-analysis, “The effect of interethnic ideologies on the likability of stereotypic vs. counterstereotypic minority targets,” published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology in 2010:

This paper examines the effect of interethnic ideologies on the likability of stereotypic vs. counterstereotypic minority targets. In two experiments, participants were exposed to either a multicultural or colorblind prime and subsequently asked to indicate their impressions of a stereotypic or counterstereotypic minority target. Results suggest that multiculturalism and colorblindness have different effects on the likability of minority targets to the extent that such targets confirm the existence of fixed or permeable ethnic group boundaries. Specifically, a stereotypic target was liked more than a counterstereotypic target when participants were exposed to multiculturalism — suggesting that multiculturalism creates a preference for individuals who remain within the boundaries of their ethnicity. Conversely, a counterstereotypic target was liked more than a stereotypic target when participants were exposed to colorblindness — suggesting that colorblindness creates a preference for individuals who permeate the boundaries of their ethnicity. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

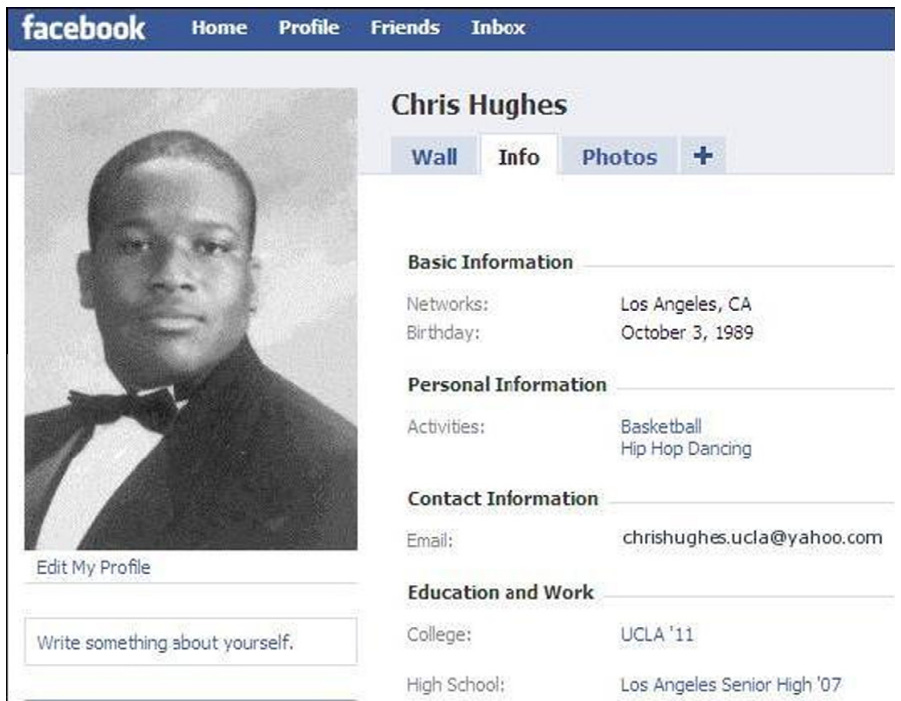

The subjects of Experiment 1 were university students, “85 women, 37 men; 50 Asians, 65 Whites, 4 Latinos, 3 participants who indicated more than one racial identity.” In Study 1 of Experiment 1, the subjects either read a short essay touting multiculturalism, a short essay touting color blindness, or a control essay discussing healthy eating. Then all the students were asked to provide their first impressions of a person based on their Facebook profile. This individual either had stereotypic interests (basketball and hip-hop dancing) or counterstereotypic ones (surfing and country dancing).

So the subjects either saw this image. . .

. . . or this one:

“To assess the targets’ likability, participants were asked to complete Wiggins’ (1979) 11-item likability scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very much; ⍺ = .88). The items in this scale are courteous, well-mannered, respectful, friendly, pleasant, tender, kind, impolite (reverse scored), uncooperative (reverse scored), impersonal (reverse scored), and unsociable (reverse scored). This scale has been used in previous research as a measure of warmth and likability (Rudman, 1998).”

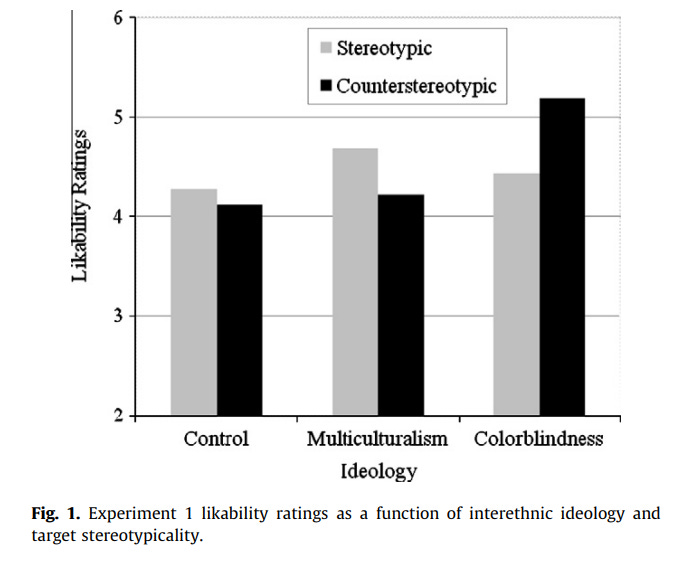

I cannot vouch for the specific statistical approach the researchers took, but at the end of the day they reported that in the multicultural and color-blind conditions, there were statistically significant differences between how the stereotypic and counterstereotypic profiles were rated. They provided a visualization of this via a graph that, for whatever reason, leaves off three points from the seven-point scale, which has the effect of making the effect size look larger than it would otherwise:

Anyway, I guess it’s not a tiny effect size given that this is just a seven-point scale? I guess a fan of color blindness could say “See? Color blindness is the best approach, because it led to the highest likability ratings overall!” Or I guess a fan of multiculturalism could say “See? Multiculturalism helps fight stereotyping!”

Except: no, this is silly.

Reading this study in 2024, knowing that around half of experimental social psychology studies fail to replicate, and that there are major problems in this field with statistical cherry-picking, premature generalization from the lab to the field, and other roadblocks to sound science, and that social priming has had a particularly rough go of it, do you think that this study provides evidence that in the real world, exposure to multicultural or color-blind primes has specific effects on how individuals view those who embody or defy common stereotypes? Do you think that, with the exception of tightly circumscribed experimental settings and claims, we can extract much of anything by asking one kid to rate another’s courteousness, manners, etc. on the basis of a paper-thin Facebook profile? Do you think the fact that the authors “replicated” this effect with a Latino target in their second experiment means all that much?

Sorry, but we should know better by now.

A Cheap And Effective Way To Counter Swingset Racism

Okay, one more experimental study that can, in theory, unlike all those correlational ones, provide us with a bit of causal oomph. In one of his emails to me, Grant said, “There are some experiments that support both causal inference and generalizability. One notable example is the Apfelbaum et al. experiment showing that fourth and fifth graders were less likely to notice and report overt racial discrimination after being randomly assigned to review a book promoting color blindness rather than recognition of differences.”

The study was published by Evan P. Apfelbaum, Kristin Pauker, Samuel R. Sommers, and Nalini Ambady in Psychological Science in 2010. It is mentioned in the bibliography of the Leslie et al. meta-analysis but lacks the asterisk they stuck next to papers they included in their quantitative analysis. Apfelbaum and his colleagues took a group of 60 eight- to 11-year-olds and asked for their help “critically reviewing a storybook that would eventually be marketed to younger schoolmates. All students accepted this advisory role enthusiastically and then viewed an illustrated digital storybook on a laptop computer. A series of illustrations were synchronized to accompany one of two prerecorded audio narratives.”

Continuing:

The content of the narrative—our experimental manipulation—was virtually identical in the two versions. The story described a third-grade teacher’s efforts to promote racial equality by organizing a class performance. In both narratives, the teacher broadly championed racial justice (e.g., “We all have to work hard to support racial equality”). At three critical points, however, the narratives diverged in their approach to advancing this aim. The color-blind version called for minimizing race-based distinctions and considerations (e.g., “That means that we need to focus on how we are similar to our neighbors rather than how we are different,” “We want to show everyone that race is not important and that we’re all the same”). The value-diversity version endorsed recognition of these same differences (e.g., “That means we need to recognize how we are different from our neighbors and appreciate those differences,” “We want to show everyone that race is important because our racial differences make each of us special”).

The students were instructed to concentrate on the “main message” so that they subsequently would be prepared to answer questions regarding the story. After its presentation (~10 min.), the children completed a series of questions about the story before a new experimenter entered and introduced them to the “real” task for the study.

The real task went as follows: a “second experimenter, blind to experimental condition, read aloud three scenarios depicting inequitable behavior alleged to have occurred at nearby schools.” The idea was to see how the students, primed with different understandings of diversity, would respond to one of three vignettes to which they were randomly assigned.

In the first, which was a control condition, a white child talked smack about his also-white “partner’s contribution to their school science project” — no racism there. The second condition was designed to provide “ambiguous” evidence of racial bias:

Most of [Brady’s] classmates got invitations, but Terry was one of the kids who did not. . . . [Brady] decided not to invite him because he knew that Terry would not be able to buy him any of the presents on his “wish list.”

And the third was designed to provide “explicit” evidence of racial bias:

Max tripped Derrick from behind and took the ball. . . . When one of Max’s teammates asked him about the final play, Max said that he could tell that Derrick played rough because he is Black. . . .

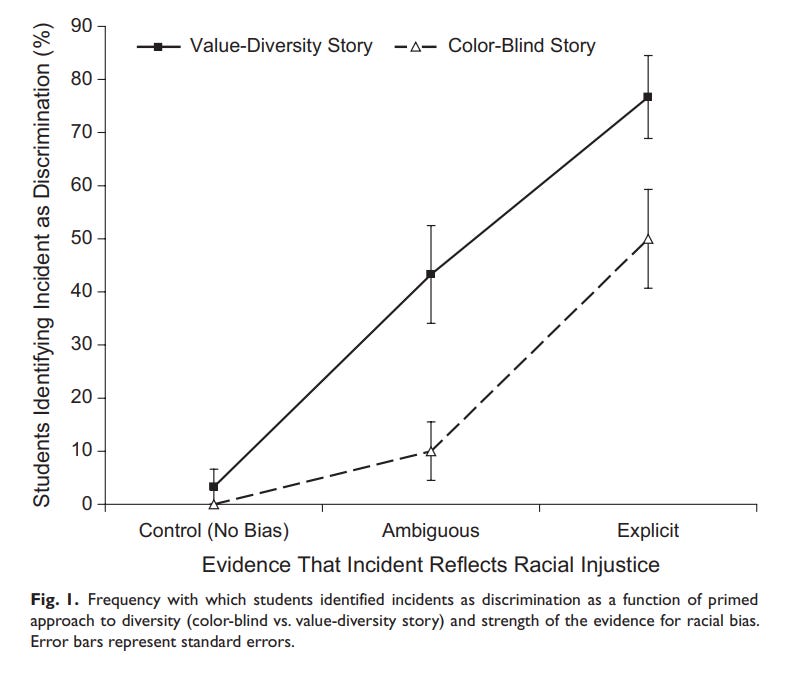

The researchers were able to generate the following results:

As you can see, the children who were exposed to the color blindness mindset were less likely to identify all three of the incidents as reflecting racial injustice, including the third, in which Max is pretty damn racist. There’s a 27-point difference — 77% of students placed in the “values-diversity” mindset described that incident as racist, while just 50% in the “color-blind” mindset did.

I have questions! For one thing, if we’re going to make much of the fact that only 50% of the kids in the color-blind condition correctly identified the racism in the explicit condition, why not also note that it isn’t great for 40% of the kids to have assumed racism motivated the actions of the child in the second condition, in which there’s no real evidence that was the case? It doesn’t appear the researchers made clear how many kids weren’t invited, how many of the kids who were invited were non-white, or that they provided other information that would allow someone to confidently state Brady’s decision not to invite Terry was motivated by racial animus.

More importantly: recall that Grant described this study as a “notable example” of research “support[ing] both causal inference and generalizability.” I guess it provides evidence that hearing the different stories caused the kids to react in different ways to the vignettes, but again, I ask: Should we necessarily care? What evidence is there that this is at all generalizable to the real world? Does anyone actually think that such a microscopic intervention — hearing one brief set of words rather than another — has a strong effect on kids’ ability to notice racism in a durable manner? That’s especially true given the ready availability of alternate explanations for this finding. For example, maybe the kids were temporarily influenced by all that talk of “ignoring race” to, well, ignore race for the purposes of the exercise? While color-blind ideals are often caricatured by their opponents, in 2024 hardly anyone, anywhere who advocates for them is saying “We should ignore explicit racism when it pops up.”

In the real world, whether or not you perceive something as racist and call it out as such is determined not only by the act itself, but by a complicated web of influences ranging from your personality to your ideological beliefs (which in most cases are likely rather stable and hard to nudge) to your social ties, among others. No one actually thinks that there is a thing called a “multiculturalism mindset” that will immediately have a causal influence on people’s ability to notice racism. This just isn’t a thing. Is it a cute experiment? Yes. Is it the sort of evidence any professional psychologist should point to not only to argue against color-blind approaches but to argue that Coleman Hughes’s talk was deeply misguided? Of course not. Is there any reason to think this result is generalizable, as Grant claimed? I’m not seeing it.

This Gets Tiring

I am not making original points, and it’s frustrating I have to reiterate them during a disagreement with such a famous and successful psychologist in 2023 and 2024. Everything I’m writing should, by now, be second nature to the Adams Grant of the world. And all these problems are likely exacerbated when it comes to politically charged subjects like race and racism.

In 2020, the University of Toronto social psychologist Yoel Inbar, who has come up previously in this newsletter, had a paper published in Psychological Inquiry titled “Unjustified Generalization: An Overlooked Consequence of Ideological Bias.”

In it, he argued that “In the case of unjustified generalization in particular, it seems very plausible that the more the explanation is ideologically appealing, the less motivated social psychologists are to think about the gap between the laboratory results and the real-world phenomena.”

He concluded his paper thusly:

I am not arguing that laboratory experiments have no value. Existence proofs can be useful, and often we want to understand psychological process rather than explain a particular real-world phenomenon. When this is the case, laboratory experiments are essential. But when it is not, we should be much more careful about generalizing from the lab to the field. Even interventions that seem strongly theoretically justified based on laboratory research (and intuitively plausible) often fail in practice (for example, see Glewwe, Kremer, & Moulin, 2009; Goswami & Urminsky, 2019; Jung, Perfecto, & Nelson, 2016). In principle, social psychologists acknowledge that generalizing beyond the lab requires extensive research. In practice, they are often perfectly happy to point to a (deliberately) simplified, reductive lab finding to explain a complex social phenomenon. This problem is likely to be particularly severe for ideology-friendly findings. This is an ironic state of affairs for a discipline whose central tenet is that behavior differs dramatically across situations. We would do well to take this tenet seriously and start with more real-world observation and less (confirmatory) experimentation, particularly when we are trying to explain important real-world phenomena.

That’s exactly what’s going on here: researchers are “perfectly happy to point to a (deliberately) simplified, reductive lab finding to explain a complex social phenomenon.” And in some cases, I do think the recent fad against color blindness and toward color-consciousness in progressive circles such as social psychology can partly explain researchers’ willingness to accept such weak evidence, though I don’t want to overstate the influence of ideology given that there are plenty of straightforward professional and social incentives nudging researchers toward shoddy work and exaggerated forms of science communication.

Then there are the structural factors. It’s worth remembering that science is hard and expensive. That’s one reason social psychology fell in love with these cute little lab experiments that could reliably produce something publishable. To actually test the causal effects of ideology on behavioral or attitudinal outcomes is an imposing undertaking. But there aren’t really any shortcuts: this isn’t like a long road trip where you’d prefer a nice meal but you settle for McDonald’s because you’re in the middle of nowhere, and McDonald’s indeed fills you up and bridges the gap to your next meal. Studies like these, whatever the subject, might honestly tell us nothing about the real-world situations we care about — the ones Coleman Hughes was discussing in his talk. And as I previously mentioned, in the worst cases they can set science and/or society down the wrong path entirely, leading to a lot of wasted effort and, sometimes, identifiable or potential harms.

So no, I don’t think I’m being overly prosecutorial here. This whole thing was kicked off by Adam Grant making a strong statement: that Hughes’s argument in his TED Talk was “directly contradicted by an extensive body of rigorous research.” You can’t make a statement this strong, cite evidence that doesn’t come close to supporting it, and then, when this is pointed out to you, muse about the dangers of people acting too prosecutorial. This whole thing started with Grant being overly prosecutorial!

A Little Bit Of A Parting Shot But I Think It’s Fair In Context

One last thing: at the end of December I got an email from The New York Times subject-lined: “Opinion: Women know what they’re doing when they use ‘weak language.’ ” It was a column by Adam Grant, who is a contributing writer for the opinion pages there, and it ran last July (I’m guessing during this holiday week the Times sends out some greatest-hits stuff from the previous year).

In the column, Grant wrote:

It turns out that women who use weak language when they ask for raises are more likely to get them. In one experiment, experienced managers watched videos of people negotiating for higher pay and weighed in on whether the request should be granted. The participants were more willing to support a salary bump for women — and said they would be more eager to work with them — if the request sounded tentative: “I don’t know how typical it is for people at my level to negotiate,” they said, following a script, “but I’m hopeful you’ll see my skill at negotiating as something important that I bring to the job.” By using a disclaimer (“I don’t know. . . ”) and a hedge “(I hope. . . ”), the women reinforced the supervisor’s authority and avoided the impression of arrogance. For the men who asked for a raise, however, weak language neither helped nor hurt. No one was fazed if they just came out and demanded more money.

I clicked “in one experiment” and it took me to a 2012 paper by Hannah Riley Bowles, a Harvard Kennedy School of Government researcher whose work I am familiar with, and Linda Babcock. I saw that Grant did not appear to be describing the paper accurately. For one thing, the researchers weren’t really studying the question of weak or deferential language directly — the paper is a bit more nuanced than that. Furthermore, while they did measure how deferential the different actors reading the scripts came across, they noted that “Deferential was not a significant mediator in either study,” meaning that it is unlikely perceptions of deference were behind the results they reported.

I emailed Bowles to ask whether I was correct that Grant had described the paper inaccurately. She responded:

That’s right: “Deferential was not a significant mediator in either study” (p. 6). We ran a simple “Relational” script (below), which enhanced the willingness to work with female negotiators, but had no effect on the willingness to grant her request (see Figure 1, p. 8).

I hope it’s OK to ask you about this. I’d feel terrible if I offended you in doing so. My relationships with people here are very important to me. [Simple negotiation script inserted here.] I just thought this seemed like a situation in which I could get your advice about this. Would you be open to talking with me about this question of higher compensation? (p. 5)

This is the closest script we ran to “weak” language, and it was not persuasive.

We found that, for women negotiating for higher pay, they could enhance others’ willingness to grant the request and others’ willingness to work with them by using a “relational account” (i.e., “a legitimate explanation for their negotiation behavior that also effectively communicates their concern for organizational relationships,” see Hypothesis 3, p. 3).

In other words, the emphasis of our research was on explaining why negotiation requests are appropriate or justified and then signaling that one is taking the interests of the counterpart or organization into account. As I have argued elsewhere, this is simply good negotiating advice.

It isn’t a lot to ask for a public-intellectual psychologist like Adam Grant, writing in The New York Times, to correctly summarize research he makes strong claims about. In the case of the Coleman dispute, he greatly overstated Lisa Leslie and her colleagues’ meta-analytic findings; in the case of the Bowles and Babcock study, he is simply not describing the actual study accurately. In both instances, he is using this research as evidence of specific claims about the world. This is what I mean about the perils of shoddy science and science communication. If pointing this out makes me seem like a “prosecutor,” then I guess I’ll see you in court.

Questions Comments? Trial dates? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The image of Coleman Hughes on stage is recycled from Part 1.

Opinions differ on the extent to which social psychology has cleaned up its act.

Grant notes his colleague's criticism of him as a "professional debunker" as though it's a bad thing for our nation's psychology professors to set out to debunk research. But that's really just the scientific method. Scientific claims are not presumed to be true -- instead, we only treat them as true if rigorous, neutral methods demonstrate that the claim provides a better explanation of a phenomenon than the dreaded null hypothesis. Professional debunkers are very important, particularly in a discipline where much research has been shown to be wrong. KEEP DEBUNKING, JESSE!

One of the problems I have with Primeworld is that it seems to imply an incoherent model of the world where there are lots of factors that each have large effects. It seems fundamentally impossible for e.g. 50 different factors to *each* explain 70% of some outcome.

Consider walking speed. Priming research tells us that observing or thinking about old people has an effect. I assume things like being late, being pursued, being in pain, being "in the moment" and taking in the world around you, etc., are also important determinants of walking speed. Given this, Primeworld seems to need to assert that one of two things must be true: either (a) we happened to discover that observing old people belongs to small number of potent stimuli which strongly affect walking speed, or (b) walking speed is an incredibly fragile property, and hundreds of small things have to be *just right* all the time in order for a person to sustain a fast or even normal walking pace. Both possibilities seem very unlikely to me.