Is There “An Extensive Body Of Rigorous Research” Undermining The Case For Color Blindness, As Adam Grant Claimed?

Fill in the blanks: _____ does not imply _____.

Three weeks ago, I wrote about the controversy at TED over Coleman Hughes’s case for color blindness. You can read the post if you want the full details, but in it I noted that the superstar psychologist Adam Grant claimed to Chris Anderson, the head of TED, that high-quality research undermines Hughes’s argument. Anderson subsequently passed that criticism on to Hughes, who wrote in The Free Press that he did not find it compelling.

I’ve had some time to look more thoroughly into this, and I’ve also emailed with Grant a bit after he initially reached out to me following the publication of my first post. I’m going to go pretty deeply into what I found — probably deeper than will seem reasonable to some readers — because I think this is a subtly important controversy.

For the last decade or so, I’ve been interested in the frequently wide gap between what scientific research says, if you examine it closely and critically, and what some people claim that it says. All too frequently, those who communicate science — and this includes scientists, activists, and journalists — make big, bold claims that sand off a great deal of complexity and uncertainty. These claims lead to widespread misunderstanding, and, when they are translated into policy decisions, to wasted time and money. (My book focused mostly on psychology, and social psychology appears to be a particularly troubled subfield of it.)

I think a version of that is going on here. It’s an unusual case, because Grant leveled his criticism privately. But he did level it, and it is a significant overstatement of the available evidence.

We should probably back up a minute to explain exactly what Hughes and Grant are arguing about. If you’re already quite familiar with the basics, you can scroll down to the “What The Meta-Analysis Says” subheadline.

What Coleman Hughes And Adam Grant Are Arguing About

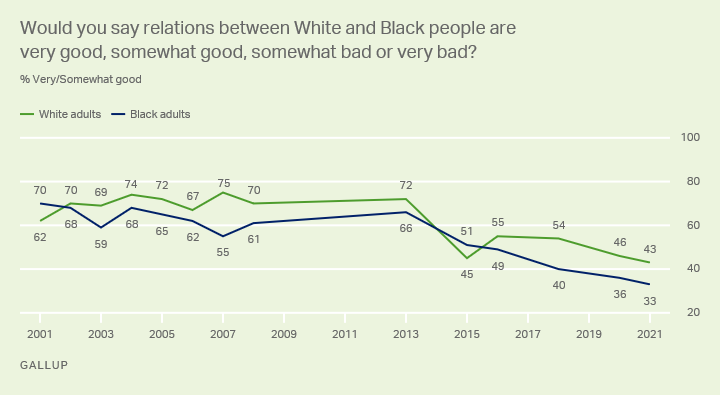

In his TED Talk, Hughes argues that “over the past ten years, our societies have become more and more fixated on racial identity.” He references this chart from Pew (projected behind him) to point out that during this same period of time, race relations in the U.S. have plummeted, with steep drops since 2013 in the proportions of both black and white Americans who believe black-white relations are at least “somewhat good.”

Hughes doesn’t explicitly connect the two events, but he obviously views them as connected, since he argues that “clearly we need new ways of thinking about race if we’re going to reverse this trend.” (Since much of this article will be about the difference between correlation and causation, it’s worth noting that race talk could be one factor causing the trend Hughes is highlighting here, but a lot of other stuff happened during this period, too, including certain advances — if you can call them that — in social media that likely supercharged outrage and polarization, the high-profile killing of Michael Brown and the unrest it triggered, and so on.)

How should we respond? With color blindness. Hughes presents an introduction and initial defense/clarification of the concept that goes as follows:

So today I’m going to offer an old idea, but it’s an idea that’s been widely misunderstood. You’ve probably heard it before; it’s called color blindness. What do I mean by color blindness? After all, we all see race. We can’t help it. And what’s more, race can influence how we’re treated and how we treat other people. So in that sense, nobody is truly color-blind. But to interpret the word color-blind so literally is to misunderstand it.

Color-blind is a word like warmhearted. It uses a physical metaphor to capture an abstract idea. To call someone warmhearted isn’t to talk about the temperature of their heart but about the kindness of their soul. And similarly, to advocate for color blindness is not to pretend you don’t notice race. It’s to support a principle that we should try our best to treat people without regard to race, both in our personal lives and in our public policy.

And you might be thinking, what’s so controversial about that? Well, the fact is the philosophy of color blindness is under attack. Critics say that it’s naive or that we’re not yet ready for it as a society, or even that it’s white supremacy in disguise.

. . .

Now, part of this reaction to color blindness is actually a fault of its advocates. People will say things like, “I don’t see color” as a way of expressing support for color blindness. But this phrase is guaranteed to produce confusion because you do see color, right? I think we should all get rid of this phrase and replace it with what we really mean to say, which is, “I try to treat people without regard to race.”

Hughes goes on to argue that, contrary to the claims of some critics, color blindness doesn’t prevent us from fighting injustice. Class-based approaches are simply better, he argues, because they better pick out who needs the most help. He doesn’t make the connection directly, I don’t think, but he seems to be drawing on the idea popularized by Matt Yglesias and many others that class-based programs will often disproportionately benefit black and other racial minority American groups anyway, because members of these groups are more likely to be poor. So the argument is that you can enact policies that won’t cause white conservative backlash (or at least not as much of it), but which will help poor people regardless of their color — a group that includes whites but which will be disproportionately non-white given the structure of inequality in the United States.

Hughes further argues that color-blind policies (need-based financial aid, the earned income tax credit) are more popular than color-conscious ones (race-based affirmative action), and that color blindness can be used to fight racism qua racism, as in the case of using speed cameras rather than police officers’ human judgment to determine who to penalize for speeding. I would have added a sentence about how you have to make sure the cameras aren’t disproportionately set up in black areas and so on, which is a known criticism of this and other ostensibly color-blind approaches, but Hughes had a limited amount of time and the broader point stands that a camera is, on its own, incapable of racially biased judgments about who deserves to be penalized for speeding.

So that’s the thrust of Hughes’s argument. Then, as Hughes subsequently noted in his Free Press article, some TED staffers got angry at the content of the talk and tried to interfere with its being published on the TED Talks website. During this period, Adam Grant sent an email to Chris Anderson that read, in part, as follows:

Really glad to see TED offering viewpoint diversity—we need more conservative voices—but as a social scientist, was dismayed to see Coleman Hughes deliver an inaccurate message.

His case for color blindness is directly contradicted by an extensive body of rigorous research; for the state of the science, see Leslie, Bono, Kim & Beaver (2020, Journal of Applied Psychology). In a meta-analysis of 296 studies, they found that whereas color-conscious models reduce prejudice and discrimination, color-blind approaches often fail to help and sometimes backfire.

Hughes subsequently argued that he didn’t think the paper actually supported Grant’s view: “I was shocked to find that the paper largely supported my talk. In the results section, the authors write that ‘colorblindness is negatively related to stereotyping’ and ‘is also negatively related to prejudice.’ They also found that ‘meritocracy is negatively related to discrimination.’ ”

Clearly we’re going to need to look more closely at this meta-analysis to figure out exactly what’s going on and who is right.

What The Meta-Analysis Says

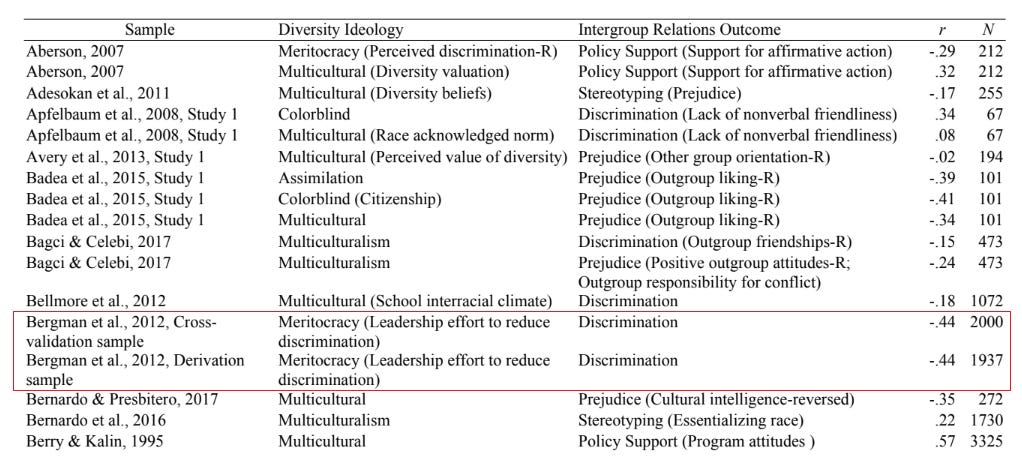

“On Melting Pots and Salad Bowls: A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Identity-Blind and Identity-Conscious Diversity Ideologies” was published in the Journal of Applied Psychology in 2020. The authors are Lisa M. Leslie, Joyce E. Bono, Yeonka (Sophia) Kim, and Gregory R. Beaver. The authors examined 114 articles containing 296 effect sizes (an individual article can include multiple studies, and an individual study can include multiple statistical comparisons that generate effect sizes), and then averaged up those effect sizes to get their results.

The abstract explains what they did:

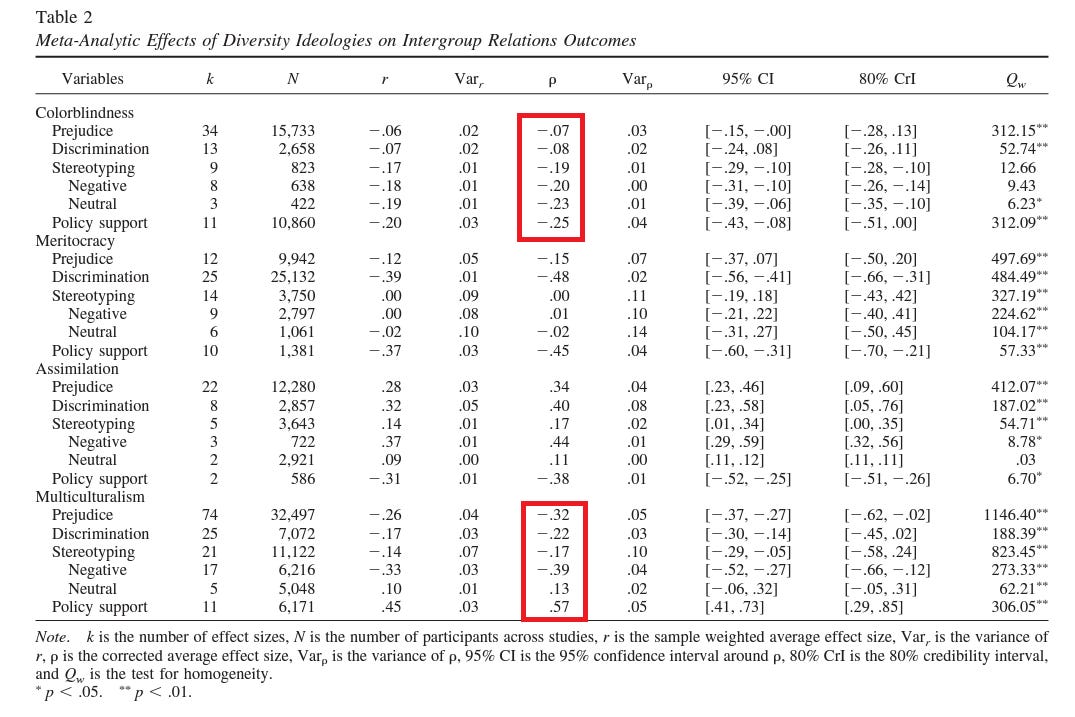

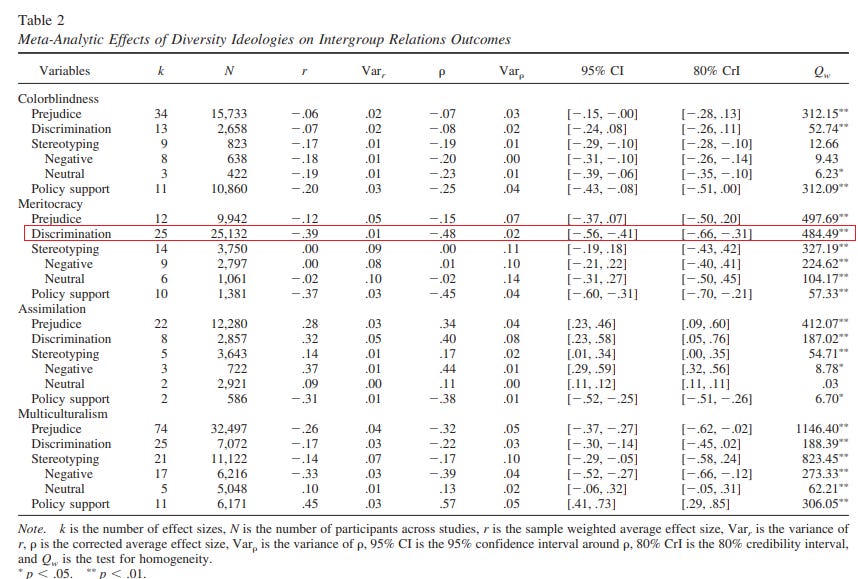

Significant debate exists regarding whether different diversity ideologies, defined as individuals’ beliefs regarding the importance of demographic differences and how to navigate them, improve intergroup relations in organizations and the broader society. We seek to advance understanding by drawing finer-grained distinctions among diversity ideology types and intergroup relations outcomes. To this end, we use random effects meta-analysis (k = 296) to investigate the effects of 3 identity-blind ideologies— colorblindness, meritocracy, and assimilation—and 1 identity-conscious ideology—multiculturalism—on 4 indicators of high quality intergroup relations—reduced prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping and increased diversity policy support. Multiculturalism is generally associated with high quality intergroup relations (prejudice: ρ = −.32; discrimination: ρ = −.22; stereotyping: ρ = −.17; policy support: ρ = .57). In contrast, the effects of identity-blind ideologies vary considerably. Different identity-blind ideologies have divergent effects on the same outcome; for example, colorblindness is negatively related (ρ = −.19), meritocracy is unrelated (ρ = .00), and assimilation is positively related (ρ = .17) to stereotyping. Likewise, the same ideology has divergent effects on different outcomes; for example, meritocracy is negatively related to discrimination (ρ = −.48), but also negatively related to policy support (ρ = −.45) and unrelated to prejudice (ρ = −.15) and stereotyping (ρ = .00). We discuss the implications of our findings for theory, practice, and future research.

I think the short and maybe annoying-to-some answer is that this meta-analysis can’t really support or debunk Hughes’s TED Talk. That’s because his talk made a considerably broader and more nuanced argument than Leslie and her colleagues’ focus, which is the effects different diversity ideologies supposedly have on various outcomes. For example, one of Hughes’s arguments was that if we want to address inequality, color-blind policies are better because they are more popular. That’s a public opinion question well beyond the scope of this meta-analysis — and while it’s a complicated one, Hughes appears to at least be generally correct that the Earned Income Tax Credit and need-based financial aid (in the form of Pell Grants) are popular among Americans, while race-based affirmative action is not (at least when you explain to them exactly what it entails).

In addition, “indicators of high quality intergroup relations” is defined in a sufficiently strange and confounded way by the meta-analysis authors that I think we need to be very cautious about connecting this paper to Hughes’s argument. This is an important point I gave short shrift until the psychology professor Robert Guttentag emailed me to let me know he had published his own concerns about the meta-analysis to Substack. As he points out, the authors, in measuring “indicators of high quality intergroup relations,” included many variables that don’t necessarily have much to do with, well, high quality intergroup relations.

Among other variables, the meta-analysis authors code support for affirmative action, support for liberal immigration policies, high ratings about outgroups on a “feelings thermometer,” and other attitudinal rather than behavioral measures, as “indicators of high quality intergroup relations.” This renders the meta-analysis even less relevant to Coleman Hughes’s talk, because Hughes surely was discussing race relations in the classical sense, not whether people can be convinced to support liberal causes (some of which Hughes himself doesn’t agree with) or score in a progressive-enough range on some psychological instrument.

Setting all that aside, the strongest evidence here in favor of Grant’s arguments is that yes, technically multiculturalism was associated with certain “better” outcomes as compared to color blindness. So while Hughes was correct to point out that the researchers found color blindness had some positive effects, overall the authors did report that it was more of a mixed bag than multiculturalism (which was the one identity-conscious ideology they studied).

Don’t fret if you don’t understand this chart from the paper, but the numbers I’m putting in the boxes reflect the correlations between color blindness and the various outcomes the authors measured (at the top) and multiculturalism and those same measures (at the bottom):

Grant argued that this meta-analysis “found that whereas color-conscious models reduce prejudice and discrimination, color-blind approaches often fail to help and sometimes backfire.” If we interpret this chart as demonstrating evidence that color blindness and multiculturalism cause these outcomes, then perhaps there’s some support for this: you could argue that since the correlation between color blindness and prejudice and discrimination are negative but pretty close to zero, they don’t prevent these negative outcomes, whereas multiculturalism does. And if you go beyond what Hughes discussed in his TED Talk and into the realm of policy preferences, then in this interpretation multiculturalism causes increased support for certain diversity policies, while color blindness reduces such support.

But that gets us to the elephant in the room here: both Grant and the authors of this meta-analysis are making many causal claims on the basis of these results, which is a large leap when you look at the articles underpinning the meta-analysis. I cannot claim to have read all 114 of them — not close, to be honest — but we have very strong evidence that the vast majority of them almost certainly can’t have provided genuine causal evidence on these questions right here, from the authors themselves: “The sample included correlational (77%) and experimental (23%) studies.”

This is an important difference. A correlational study simply tells you, the researcher, whether when a value, X, is higher, another value, Y, also tends to be higher, or lower, or to not appear to have any relationship to X. Of course this is super oversimplified and you can have multiple variables and so on, but at no point are you manipulating things in a manner that allows you to uncover suspected causal relationships (that is, running an experiment). As one research methods e-textbook I found on the National Institutes of Health’s website puts it, nice and plainly, “A general limitation of a correlational study is that it can determine association between exposure and outcomes but cannot predict causation.” The context is health studies, but the principle applies to all areas.

Despite this, Lisa Leslie and her colleagues use causal language in both the abstract and throughout the article. In the abstract, they discuss how their goal is to better understand “whether different diversity ideologies… improve intergroup relations,” and to “investigate the effects of 3 identity-blind ideologies… on 4 indicators of high quality intergroup relations[.]” They conclude there that “Different identity-blind ideologies have divergent effects on the same outcome[.]” The body of the article, too, is littered with this sort of language. The authors write that “we investigate the consequences of three identity-blind ideologies,” “[w]e consider the effect of each ideology on. . . ,” and so forth (there are plenty of other examples). Then, in their “Implications for Practice” section, they explain how their meta-analysis provides some guidance about improving outcomes in organizations where one ideology or another is dominant (by instead nudging members toward another), which really only makes sense if they understand these relationships as causal. While the authors briefly nod to this issue here and there, noting near the end the paper, for example, that “tests of whether the effect of diversity ideologies on intergroup relations or the effect of intergroup relations on diversity ideologies is stronger is an avenue for future work,” they effectively ignore it for most of the meta-analysis. (They also write in a footnote that they didn’t have sufficient statistical power to test whether there were meaningful differences between the results of the experimental versus correlational studies.)

That’s how Grant interpreted the meta-analysis: as causal evidence for the comparative effects of different ideologies on intergroup outcomes. And it’s fair in the sense that that’s what the authors are claiming. While Grant and I got into a slightly in-the-weeds-disagreement about the extent to which the authors used causal language, 1) you can read our correspondence here if you want the details (Grant gave me permission to share it), and 2) it’s indisputable that causal language is littered through the paper and motivates Grant’s own claim about what the study shows. The authors of the meta-analysis are, by their own language, clearly interested in — and believe they are measuring — what causal effect different diversity ideologies have on indicators of high quality intergroup relations. (Grant did say in one of his emails: “As a stickler, given the mix of experimental and correlational studies, I would’ve still written ‘to investigate the relationship between. . . ’ But this lingo is so widely used that it’s probably a losing battle in academia.”)

Of course, like all basic principles, correlation-does-not-imply-causation should be leavened by common sense. To use a dark example, if I find there is a correlation between 30-year-olds being diagnosed with Stage IV cancer and being dead three years later, and you say “Well, that’s not proof of a causal relationship between having Stage IV cancer and dying in your thirties or early forties,” then I will not be inviting you to my next happy hour. But that’s an extreme case, because we’re arriving at that particular correlation with a solid preexisting understanding of what Stage IV cancer is and does, and we can use that to make the very strong case that this particular correlation reflects a causal relationship.

The situation with this diversity ideology meta-analysis is different, because we have no good reason to believe that ideology causes the outcomes observed in the studies in this meta-analysis — especially given how many of the outcome measures are really just attitudes rather than instances of real-world or lab discrimination. It could just as easily be the case that in many instances, people are liberal because of genetics or upbringing or some combination of the two, which causes them to be in favor of liberal policies in general (because they socialize with other liberals, or read about being a liberal and discover that this is the “correct” viewpoint), and then they retroactively justify this position by endorsing liberal ideological beliefs. Or maybe there’s some other causal pathway, or maybe it varies from person to person. (And of course, third or fourth or fifth or X many variables could be causing both, or intertwined in complex ways with both.)

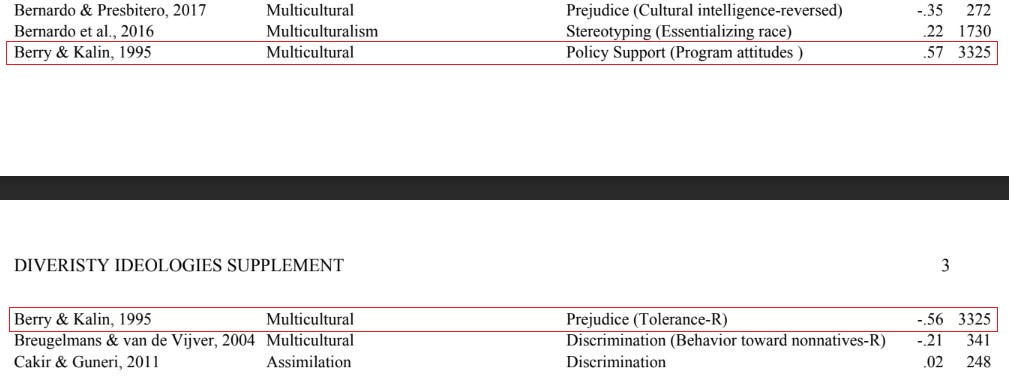

Let me provide an example of just how poorly equipped some of the correlational studies in this meta-analysis are to establish the causal relationships the authors are interested in. This supplementary appendix lists all the studies and their effect and sample sizes in one place. If pull it up, you’ll find that one of the largest samples came from “Multicultural and ethnic attitudes in Canada: An overview of the 1991 National Survey,” published in 1995 by J. W. Berry and Rudolf Kalin in the Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. According to the authors of the meta-analysis, Berry and Kalin found an r = .57 correlation between “Multicultural” diversity ideology and “Policy Support (Program attitudes),” as well as a r = −.56 correlation between “Multicultural” diversity ideology and “Prejudice (Tolerance-R)” — some of the larger effect sizes in the meta-analysis. (The R tacked onto the end just indicates reverse coding.)

(The sample sizes are a bit off because the authors of the Canadian researchers apparently didn’t get responses from the full sample on every item. I think the first n should be 3,313, and the second should be 3,316.)

Leslie and her colleagues are talking about these three items from the Canadian study:

Program Attitudes. This scale measures the degree of support vs. opposition to nine “possible elements of federal multiculturalism policy”. . . . Two examples are supporting or opposing “Ensuring that organizations and institutions reflect and respect the cultural and racial diversity of Canadians,” and “Developing materials for all school systems in Canada to teach children and teachers about other cultures and ways of life.”

. . .

Multicultural Ideology. This scale assesses support for having a culturally diverse society in Canada, in which ethnocultural groups maintain and share their cultures with others. There are ten items. . . [T]wo advocate “assimilation” ideology, one advocates “segregation,” and two claim that diversity “weakens unity.” Two examples are supporting or opposing the view that “Recognizing that cultural and racial diversity is a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society,” and agreeing or disagreeing that “The unity of this country is weakened by Canadians of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds sticking to their old ways” (Reversed).

Tolerance. This scale is made up of nine items that assess one’s willingness to accept individuals or groups that are culturally or racially different from oneself. There are four items phrased positively (i.e., indicating tolerance) and five items phrased negatively (i.e., indicating prejudice). Thus the scale is nearly balanced. A high score is indicative of tolerance. Two examples are agreeing or disagreeing that “It is a bad idea for people of different races to marry one another” (Reversed), and “Recent immigrants should have as much say about the future of Canada as people who were born and raised here.”

So the higher someone scored on the Multicultural Ideology scale, the higher they scored on the Program Attitudes scale, and vice versa. Does this mean exposure to the diversity ideology of multiculturalism causes heightened support for these policies? Of course not! There are countless other possible reasons these two variables might be correlated. The most obvious one is that liberals tend to endorse both multiculturalism as an ideology and policies promoting multiculturalism, while conservatives tend to be more skeptical of both. There’s really no evidence here to suggest any particular causal relationship.

Similarly, the higher someone scored on the Multicultural Ideology scale, the higher they scored on the Tolerance scale, and vice versa. Does this mean exposure to multicultural ideology causes heightened tolerance, as measured by this scale? Of course not! There are countless other possible reasons these two variables might be correlated. The most obvious potential missing variable is, again, political leanings.

But these findings subsequently were interpreted by Leslie and her colleagues as evidence of the “effect” of multicultural ideology “on” an “indicator[ ] of high quality intergroup relations” — as evidence that exposure to multicultural ideology causes more support for multicultural policies and tolerance, as defined by these scales. There’s no reason to favor this particular interpretation.

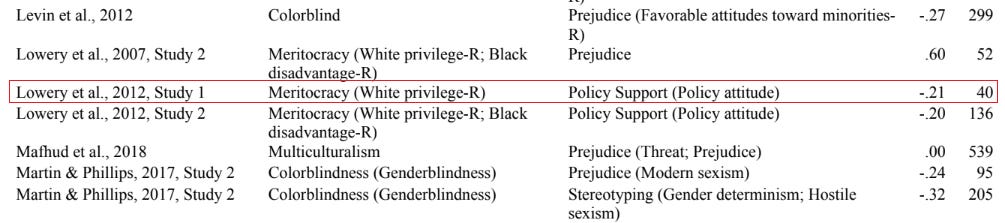

As another example, take a 2012 Journal of Personality and Social Psychology article called “Paying for Positive Group Esteem: How Inequity Frames Affect Whites’ Responses to Redistributive Policies.” The authors are Brian S. Lowery, Rosalind M. Chow, Eric D. Knowles, and Miguel M. Unzueta. Lisa Leslie and her colleagues coded that paper’s first two studies as finding negative correlations between the ideology of meritocracy and policy support.

Let’s just tackle the first result Leslie and her colleagues list. In Study 1, Lowery and his colleagues measured 40 white online survey respondents’ views on white privilege and white guilt. Then they were presented with a hypothetical hiring policy in which race would be used as a tiebreaker between a pair of equally qualified white and black finalists, favoring the black applicant. Then they were asked, among other items, how much they would support that policy relative to having no affirmative action policy at all. It shouldn’t surprise us that those who endorsed the view that white people have unearned advantages in society were more supportive of an affirmative action policy (as were those who scored higher on the white guilt measure). All the above problems inferring causality apply: political liberals are more likely than conservatives to think whites have unearned advantages, and are also more likely to support race-based affirmative action in general.

In other instances, it’s even harder to assume these correlations reflect causal relationships between ideology and outcomes of interest. For example, Leslie and her colleagues included two findings from a large 2012 study titled “Racial/ethnic harassment and discrimination, its antecedents, and its effect on job-related outcomes” by Mindy E. Bergman, Patrick A. Palmieri, Fritz Drasgow, and Alayne J. Ormerod, published in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology.

The effect (r = −.44) and sample sizes (n = 2,000 and n = 1,937, so a total of 3,937) are pretty big, the sample size especially so given that the total sample for all the meta-analysis’s studies linking Meritocracy diversity ideology to Discrimination outcomes is 25,132.

The problem is that this study does not appear to have much to do with diversity ideology. Or at least I didn’t think so — when I initially read it, I thought it had been included accidentally. But Bergman disagreed with me when I emailed her, saying that “from the quick look I’ve taken, the authors have faithfully represented my work[.]” When I raised the issue with Grant, meanwhile, he suggested that this is simply an instance of the authors of a meta-analysis including any and all studies that satisfy their inclusion criteria, even ones that might not superficially seem to fit. (I emailed Lisa Leslie and all the other authors of the meta-analysis about this and some other issues, and didn’t hear back.)

Obviously I’m putting myself in a vulnerable and potentially foolish position by pressing my skepticism further, given that the author of the study herself doesn’t see any problems with including her study in the meta-analysis, but let me at least explain my argument that this is a very shaky way of approaching the question of how diversity ideologies are correlated with — let alone cause — certain intergroup outcomes.

Bergman and her colleagues’ study is about members of the military’s exposure to racial/ethnic harassment and discrimination (REHD) and their views on whether they thought their leaders took that problem seriously. The more seriously respondents thought their leaders took efforts to combat REHD, the less severe they rated their own experiences with it in the military (as measured by a 14-item instrument capturing negative experiences based on race or ethnicity ranging from overheard discriminatory jokes to physical threats and ostracization). It makes sense that there would be a connection between experiencing negative events and lacking faith in the ability of leaders whose job it was to stop them. But this got coded by Lisa Leslie and her colleagues as a correlation between — this is their language — the “diversity ideology” of “meritocracy” and the “negative outcome” of “discrimination.”

If we look at how Leslie and her colleagues conceptualized “Meritocracy” and compare it to the exact language Bergman and her colleagues used to describe the variable capturing faith in leadership in this particular study, I think you’ll see the problem:

Leslie study: “We operationalized meritocracy as beliefs that emphasize the equitable treatment of versus discrimination against demographic groups (e.g., ‘Many social barriers prevent people from ‘minority groups’ from getting ahead’; Foster & Tsarfati, 2005; reverse coded).”

Bergman study: “Leadership efforts were assessed with three items with the single stem, ‘In your opinion, do the persons below make honest and reasonable efforts to stop racial/ethnic discrimination and harassment, regardless of what is said officially?’ (0 = no; 1 = don’t know; 2 = yes). The leaders were: senior leadership of the Service, senior leadership of the installation/ship, and immediate supervisor.” [Emphasis in the original in both cases.]

I will obviously defer to the author herself that the meta-analysis authors were correct to include this study and code it as meritocracy, but to then interpret it as evidence that meritocratic beliefs are correlated with protection from harassment just seems like a real stretch, and to be well outside the spirit and goals of the meta-analysis given the narrow scope of the leadership efforts item. It clearly was not written to capture respondents’ more general views about the nature of justice for marginalized people in the world — it was written to capture whether a specific group of people in specific organizations thought their leaders had done well at a specific task.

It’s a minor thing, but it also looks like Leslie and her colleagues may have reported the wrong r-value, r = −.44, for both the derivation and cross-validation samples. The correct values, from the paper, appear to be −.48 and −.47, respectively.

***

I only looked at a handful of the correlational studies covered by this meta-analysis. But I hope I’ve fairly and accurately communicated why we should be very hesitant about any attempts to use them to justify causal theories about the relationship between diversity ideologies and outcomes pertaining to intergroup relations.

I’m going to leave it at that for now. In the next couple weeks, hopefully, I’ll publish Part 2. In that one, I’ll address the studies in this meta-analysis that are experimental, as well as some other examples of research that Adam Grant sent me to bolster his case. Can they tell us much about the color blindness debate?

I’ll also respond to an important claim Grant made in our correspondence:

I think an unintended consequence of the replication crisis is that critics often approach a body of research like prosecutors seeking a conviction. That makes it easy to discount arguments based on the weakest evidence. (I know from experience—a colleague once warned me that I was at risk of becoming a “professional debunker” thanks to my tendency to flip into prosecutor mode when I think someone is preaching based on flawed data or a one-sided argument.)

Is this a fair critique?

More soon.

Questions? Comments? Argument that correlation does imply causation? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com. The leadimage is Lionel Hutz’s vision of a colorblind world without lawyers.

My two cents on the last question Grant asked, whether we should be worried about being TOO dismissive of potentially weak studies: good god, no. I'm a lawyer, not an academic, but my legal career has put me in frequent close contact with academic social scientists and their work product. While frequently lovely people, far too many of them end up as impressively-credentialed BS artists who are much, MUCH more likely to wave away obvious problems/limitations with their work, and the work of their colleagues, than they are to take those limitations too seriously. As a profession, social scientists can't really be trusted to police the flow of shoddy social science into the world. It's appropriate to default to skepticism about social science "findings."

It’s also worth pointing out that the way Coleman defines colorblindness is completely orthogonal to multiculturalism. One can (and should!) learn about and celebrate cultural differences while eliminating race from public policy and striving to avoid prejudice in personal interactions.