Why You Should Try Not To ‘Theyify’ Your Perceived Ideological Enemies

The world is complicated, Part 2347821273

I’m jealous of Michael Moynihan for coining a term on the most recent episode of The Fifth Column: theyification.1

At about 30:05 in the episode, which includes a very interesting interview with Ben Smith about his new book, he and Matt Welch discuss the strange video Tucker Carlson posted online after being ousted from Fox News. Welch argues that half of the video was gracious and normal, but the other half was “conspiratorial claptrap of the kind that he has been trafficking in very strongly for the last several years in his Trumpism-without-Trump era, where you say these kind of airtight descriptions of — totalist visions of what the media is doing, what they are trying to do.”

Moynihan responds that the video actually inspired him to type a short note into his Notes app: “the theyification of Tucker.” I really like this term, though I’d use it a bit differently — it’s not Tucker being theyified, but rather Tucker doing the theyifying. They’re doing this; they’re doing that; they won’t let you hear about the truth, and certainly won’t let you express it without repercussions. As Welch and Moynihan note, this is common language among conspiracy theorists.

As a result, it’s easy to make fun of. But it comes from a very human, instinctual place, and we all do it to one extent or another. I think it’s hard to avoid this cognitive tendency unless we’re intentional about it, unless we build strong counter-theyification muscles.

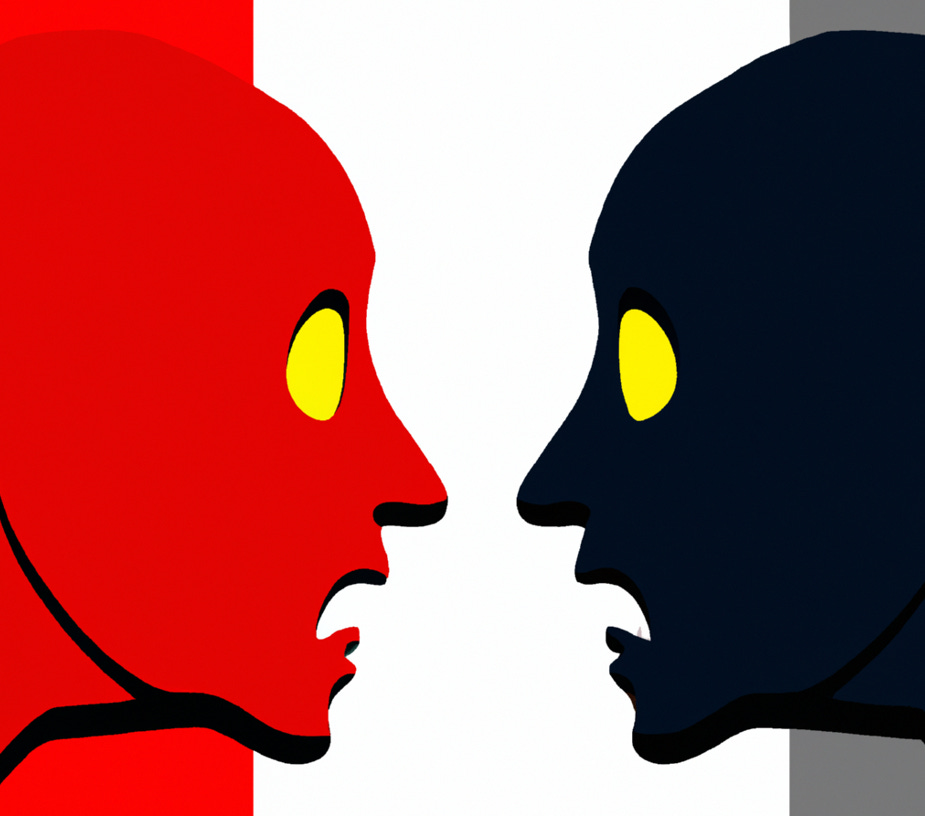

At the risk of slightly oversimplifying human cognition, I do think certain types of thinking and feeling come to us very easily. It is easy to trigger fear or happiness, because these feelings serve really important evolutionary functions. It’s also easy to trigger warm feelings for us and negative feelings for them. And us/them thinking leads to a lot of distortion and essentializing, including theyification.

A working definition of theyification might go something like: the act of treating one’s political enemies or perceived enemies as a unified bloc driven by unusually nefarious motivations rather than common human ones. To take a relevant example, the “great replacement” conspiracy theory Carlson helped to propagate is classic theyification. It explains liberal beliefs about immigration not in terms of different values or different calculations of various trade-offs, but rather as a national or international conspiracy: they want to import darker-skinned immigrants who will vote Democratic, and they don’t care what effect this has on native-born Americans.

Every political tribe does this to every other political tribe. Republicans are against abortion because they favor patriarchal systems of authority; Democrats are for abortion access because they couldn’t care less if babies die as a result of their ill-conceived quest for “sexual liberation.” Give me a subject and a political tribe in the States, and I can probably give you the theyified version of how they see the other.

But of course these accounts vastly oversimplify why people believe what they believe. When theyified theories are expressed, it’s less to provide accurate information about the other side’s beliefs and more to 1) demonstrate one’s allegiance to one’s tribe; and 2) shore up the base (as it were) by raising awareness of just how incorrigible the other side is.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Singal-Minded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.