Why Would I Possibly Trust Bill Adair Or PolitiFact To Determine Which ‘Misinformation’ Should Be ‘Suppressed’?

If their performance covering the unrest in Kenosha is any indication, they have no grounds for stone-throwing

I’m unlocking this article on 1/7/2025, in light of this announcement from Facebook’s parent company, Meta, that it will be ending its American fact-checking partnerships on Facebook in favor of a new, crowdsourced “Community Notes”-style feature. PolitiFact was one of the partners in question.

If you find this sort of commentary useful, please consider becoming a paying subscriber.

Nieman Lab recently ran a roundup of year-end predictions for 2024, and Bill Adair argued in one of them that “Fact-checking needs a reboot.” Adair, his bioline at the end of the article notes, “is founder of PolitiFact and the Knight Professor of the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University.”

The first sentence argues that “Fact-checking is failing.” Adair continues: “The old way of publishing fact-checks — putting them on websites and promoting them through social media — isn’t getting them to the people who need them. It’s time to reimagine how fact-checkers publish and broadcast their work.”

You can read the article if you want to get his full argument. He makes some perfectly fair points about how, for example, state legislators are subjected to very little of the fact-checking that sometimes covers higher-profile politicians.

But I’d like to focus on one part that really jumped out at me:

After I founded PolitiFact in 2007, I often said that our goal wasn’t to change people’s minds or get politicians to stop lying — it was simply to inform democracy. In the last few years, I’ve changed my mind. “Informing democracy” is not enough in an age of rampant lies about elections and public health and climate. Fact-checkers need to be more assertive in getting truthful information to the audience that needs it.

In 2024, they will dream up new ways of getting the facts to the people who need them. Fact-checkers will be bold and think more like marketers trying to push content rather than publishers waiting for the audience to come to a website. They will experiment with new forms that target the people who are misinformed and push the content directly to them.

Another way they will innovate: They’ll get tech companies and social media platforms to expand the use of fact-checking data to suppress misinformation. My Duke team helped develop ClaimReview, a tagging system used by most of the world’s fact-checkers. Tech companies such as Google use it to identify fact-checks and highlight them in search results and news summaries. But this is just a start. ClaimReview and MediaReview, a sibling tagging system for fact-checks of videos and images, can be used more widely to suppress inaccurate content.

I suspect that by “in the last few years,” Adair means something like “since Donald Trump was elected.” After all, countless journalists have decided since then that they need to be a little bit more “assertive” about what they do — that they cannot merely “inform democracy.”

As I’ve argued before, from a certain perspective it all sounds well and good — until you dig down into the specifics, into how journalists actually execute on their new supposed imperative. In this case, it’s telling that a journalism professor would speak this breezily about “suppress[ing] misinformation” without any critical inquiry into what that might mean.

This article fits neatly into a recent obsession, in some liberal circles, with the idea that the United States can fact-check its way out of various social ills and political crises. This has brought with it some fairly ominous-seeming ideas about what a “fact” is and who gets to “check” it. In this case, Adair offers no hint as to how we should determine what crosses so far into “misinformation” that it should be suppressed. Not “corrected,” not “contextualized via a note from an editor” — suppressed!

Even though he doesn’t say so, it stands to reason that as anti-misinformation technology improves (or “improves”) and more misinformation (or “misinformation”) is suppressed, it’ll be the Bills Adair of the world and their PolitiFacts that get to determine what is sufficiently untrue as to warrant suppression. This raises an obvious question: How have they done so far?

One relatively easy way to evaluate the quality of fact-checking organizations is to judge their past performance. Specifically, their past performance on the most politicized, incendiary cases. If a fact-checking organization can keep a steady eye on its principles even in these instances, that’s a good sign that it is functioning well and can be trusted.

I continue to think that the chaos that unfolded in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in August 2020 was a vitally important test case for mainstream American journalism. To review: first, Jacob Blake was shot seven times by Kenosha police officer Rusten Sheskey on August 23, sparking both peaceful protests and rioting. In the chaos that ensued, Kyle Rittenhouse, a teenager from a nearby town in Illinois who styled himself a guardian of the increasingly dangerous streets, shot three individuals, two fatally, late in the day on August 25.

Despite all the outrage over Sheskey’s and Rittenhouse’s actions, the available evidence suggests that Sheskey’s use of potentially lethal force against Blake on August 23 was almost certainly justified, legally speaking, and that Rittenhouse almost certainly acted in self-defense (also legally speaking) as well, since the men he shot were pursuing him. Therefore, the Kenosha County District Attorney was correct when he announced he wouldn’t pursue any legal charges against Sheskey in early 2021; the Department of Justice was correct when it announced it wouldn’t pursue federal charges nine months after that; and later, a jury was correct to acquit Rittenhouse on charges that included intentional homicide.

I’m not going to rehash these cases in detail here, but to be honest I don’t think either of them is much of a close call, and I’ve written and said plenty about both for readers who are curious to know more: here’s what I wrote about the Rittenhouse case in the early days of that controversy; here’s an episode of Blocked and Reported Katie Herzog and I dedicated to carefully going through the Jacob Blake case; here’s a piece I wrote for Persuasion about how the not-guilty verdict shouldn’t have surprised anyone following the Rittenhouse case closely (and how badly journalists screwed it up); and here’s an episode of Honestly in which I discussed the verdict with Bari Weiss.

Why would I choose these particular events as a quality-control test for journalists and their outlets? Partly because it’s convenient for me — I know a fair amount about the events in question. But beyond that, these events constitute fairly clean means of assessing journalistic competence because 1) they were ultra-polarizing, meaning that during the heady days of 2020 and 2021 there was tremendous pressure for partisan actors and institutions to express the “correct” opinions about them (and there still is, to a lesser extent); 2) we have a lot of useful video about what actually happened in both instances; and 3) Blake’s shooting sparked two investigations (both the DA’s and an independent one by Noble Wray, a law enforcement veteran and former Barack Obama police-reform appointee, which the DA relied on in part to make its decision), while Rittenhouse’s led to a court case, and both of these processes produced yet more evidence.

In other words, journalists had (and have) a great number of social and political reasons to get Kenosha wrong, but few excuses to do so when it comes to the available evidence, which is not in short supply. It’s a low bar to clear and professional journalists should have been able to hurdle it from the start.

PolitiFact has basically failed this test.

***

It’s not that PolitiFact’s work on Kenosha was entirely without merit. For example, here is a pretty good article by Laura Shulte debunking Rep. Jerrold Nadler’s post-acquittal claim that Rittenhouse was an “armed person[] crossing state lines[.]” It also includes some useful information about why the gun charge against Rittenhouse — the one charge he wouldn’t have been able to evade with a self-defense claim — was tossed out by the judge.

But PolitiFact also stepped on a lot of rakes — and exactly the rakes you’d expect from a left-of-center website, even one that claims to be nonpartisan, operating in 2020 and 2021. Most tellingly, it never provided updated accounts for readers explaining exactly what went on and why Sheskey and Rittenhouse ended up evading legal consequences.

Here it’s useful to rely on the site’s own summary of its work on Rittenhouse, published in November 2021 as the jury was deliberating. At that relatively late date, PolitiFact continued to bungle at least one very basic aspect of the case:

Claim: A video shows Rittenhouse “was trying to get away from them . . . fell, and then they violently attacked him.”

Our ruling: False.

The statement was made by [Donald] Trump.

Rittenhouse tripped and fell as a group of people pursued him. But Trump’s claim left out vital context: that Rittenhouse ran away from protesters after, according to prosecutors, he had already shot and killed someone.

“False” points to the original fact-check in question, which was published by Haley BeMiller on September 1, 2020. While BeMiller grants that Trump got “minor” details of the night correct in what was then a recent press briefing, she goes on to accuse him of “gross” acts of misinformation:

In an Aug. 31, 2020 media briefing, on the eve of his visit to Kenosha, Trump defended Rittenhouse’s actions when asked about the teenager.

“You saw the same tape as I saw,” Trump said. “And he was trying to get away from them, I guess; it looks like. And he fell, and then they very violently attacked him. And it was something that we’re looking at right now and it’s under investigation.”

He went on to say of Rittenhouse: “I guess he was in very big trouble. He would have been — I — he probably would have been killed.”

The president correctly describes some minor details about that night. But overall, his comments grossly mischaracterize what happened — leaving out that by the time of the events he described, prosecutors say Rittenhouse had already shot and killed a man.

In this fact-check, we are not examining the question of whether Rittenhouse acted in self-defense, as his attorney claims. We are examining whether Trump is providing an accurate description of what happened by focusing on only a portion of the events of that night.

He is not.

What did he get wrong? Remarkably, nothing that follows actually debunks Trump’s claim. The closest BeMiller comes to explaining how Trump was wrong is when she writes that “Trump’s comments completely overlook the fact that people started following him after he allegedly shot and killed someone.” Yes, but 1) that doesn’t make Trump’s claim false, and 2) as BeMiller has already explained by this point in the article, the first person Rittenhouse shot had chased him, closed in on him and, according to a reporter who saw the first shooting, was trying to grab his gun. So Trump’s claim that “he was trying to get away from them” applies to every single person Rittenhouse shot. This was widely known by August 27, 2020 — several days before BeMiller’s article went up — which was when an exceptionally useful New York Times visual investigation compiled a bunch of social media footage to grant a rather clear rundown of what had happened that deadly evening. (It also showed that immediately before Rittenhouse opened fire, he turned toward the sound of a gun being fired into the air nearby, which constitutes further evidence he had reason to fear for his life.)

BeMiller then wrote that Trump “also claimed protesters ‘violently attacked’ Rittenhouse, but that is not fully supported by the videos, either.” Immediately prior to this section of her piece, though, BeMiller explained the following about what happened after the first shooting:

In a video, Rittenhouse can be heard saying on his cell phone, “I just killed someone.”

Rittenhouse began running slowly down the street as a crowd began to follow him, with some people shouting “get him!” and shouting he just shot someone. Rittenhouse tripped and fell.

While he was on the ground, police say, he appeared to fire two shots at a man who jumped over him but missed.

After that, Anthony Huber, 26, ran up to Rittenhouse with a skateboard in one hand and appeared to hit him with it before reaching for Rittenhouse’s gun. Rittenhouse fired one round that hit Huber in the chest and killed him.

Rittenhouse sat up and pointed his gun at Gaige Grosskreutz, 26, who had started to approach him. Grosskreutz took a step back and put his hands in the air, but then moved toward Rittenhouse, who fired a shot that hit Grosskreutz in the arm.

Grosskreutz had a handgun. It is unclear whether Grosskreutz was pointing the gun at Rittenhouse, or if Rittenhouse saw that Grosskreutz had a gun.

So Haley BeMiller, the professional fact-checker, wants us to know that 1) Rittenhouse was chased by a group of people, 2) one of his pursuers appeared to hit him with a skateboard and reached for his (Rittenhouse’s) rifle, 3) another one of his pursuers had a gun and was maybe pointing it at him1, and, deep breath, 4) the claim that Rittenhouse was “violently attacked” is “not fully supported by the videos.”

Fact-checking!

PolitiFact doesn’t do much better with Jacob Blake. If you search for the site’s mentions of him, you’ll find a bunch of stuff, and it basically follows the same pattern as the coverage of Rittenhouse. While the site usefully clears up misinformation here or there, overall it fails to do its most important job: explaining to readers exactly what happened, even if that means challenging their biases and misconceptions.

For example, on August 24, 2021, here’s the start of an article titled “Fact checking Kenosha shootings, violent protests one year later” by Vanessa Swales:

It began Aug. 23, 2020, when a Kenosha police officer shot 29-year-old Jacob Blake seven times from behind. Blake survived but is paralyzed from the waist down. Blake has since filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Officer Rusten Sheskey, who was not criminally charged, saying Sheskey used excessive force.

“Who was not criminally charged,” which goes linkless, obscures a huge amount of information that was known by August 24, 2021. The Wray report carefully went through the episode, moment by moment, and explained why the officers at the scene’s actions were justified, including Sheskey’s decision to use potentially deadly force.

You really can just read the report — it is not long and many people would be well-served by reading it rather than continuing to be deeply misinformed about what happened on August 23, 2020 — but the short version is that: police arrived on scene knowing Blake had an open felony warrant (for sexual assault) and that they were therefore required to apprehend him. Upon arrival, the officers saw him put a child in the back seat of an SUV. Blake violently resisted their attempts to arrest him, and the ensuing fracas swiftly escalated to the officers wrestling on the ground with him and attempting to tase him. Blake had a knife in his hand for part of this encounter, and on some of the video you can hear the police demanding he drop it. In the moments immediately prior to being shot, Blake managed to free himself and, in an apparent attempt to get away, walked toward a vehicle with a kid in the backseat.

Sheskey would later tell investigators that at this point he determined he couldn’t let Blake escape and risk a high-speed chase involving a child. Sheskey tried to pull Blake back toward him, away from the car, but Blake continued to resist. Then, Blake appeared to swing his knife up toward Sheskey, prompting the officer to open fire. Or that’s what Sheskey and his colleagues claim — this is the one part that can’t be dispositively confirmed via video due to the position of the car door, which obscures the action. But a knife was found on the floor of the driver’s side of the car, which supports this claim, as do Blake’s bullet wounds, which were on his side and back in the pattern one would expect if, as Sheskey claimed, Blake was turning in a counterclockwise stabbing motion. The Kenosha County DA announced on January 5, 2021, that no charges would be filed against Sheskey partly, as the Times summed it up, “because it would be difficult to overcome an argument that the officer was protecting himself.” In October of that year, federal civil rights investigators would come to the same conclusion. Blake himself admitted to having the knife — he said in an interview that he dropped it during the encounter and then picked it up, which he shouldn’t have done.

So as is often the case with viral videos, the infamous initial video of Blake appearing to get shot in the back for little discernible reason left out a tremendous amount of vitally important context. No one has come close to explaining how, under the applicable laws and rules, this wasn’t a justified shooting.

Back to PolitiFact: Swales’ rundown of Blake’s shooting, written seven and a half months after the DA’s decision, is absolutely frozen in time. The only link to a story about the details of the actual shooting points to contemporaneous Milwaukee Journal Sentinel coverage containing few of the facts that would later emerge and lead Sheskey to be cleared from facing any charges. Swales can’t even get the exact position of the bullet wounds exactly right: the DA’s report, which was released January 5, 2021, noted: “There were four entrance wounds to Jacob Blake’s back and three entrance wounds to his left side (flank).” Meaning this would have been a very simple thing for PolitiFact to not get wrong. (Listen to our episode for more background on all of this.)

If PolitiFact has any purpose, it is dispelling false but passionately held beliefs. The belief that Blake was shot seven times in the back, in a legally unjustifiable manner, is one of those beliefs. Yet here PolitiFact is, eight months after vital new details had come to light, failing to update readers’ basic understanding of what had occurred. Any reader who arrives at PolitiFact believing Jacob Blake was shot in the back is going to read “shot from behind” as “shot in the back.” This reader will also not come away with any of the most crucial details about the case, because they’re entirely absent from Swales’ coverage. The name “Noble Wray” has not appeared on PolitiFact once.

That’s not the only example of PolitiFact covering the Blake shooting in a strange and incomplete manner. Within a week of the shooting, Eric Litke wrote an article for the site responding to an apparently-then-viral Facebook post. It was (and is) headlined “No evidence that Jacob Blake ‘brandished’ a knife, got a gun before police shooting in Kenosha.” It is true that Blake didn’t have a gun — that was an early false rumor — but we now know that there’s in fact rather strong evidence that Blake did more than just “brandish” a knife before getting shot — he most likely attempted to stab a police officer with it! I know we can tie ourselves into knots with semantics here — I guess technically if I stab you with a knife without first threatening you with it, at no point did I brandish it — but surely this is, in 2023, an inaccurate headline? How can PolitiFact have reported that there was “no evidence” to support the claim that Blake brandished a knife when he probably attempted to stab a cop with one?

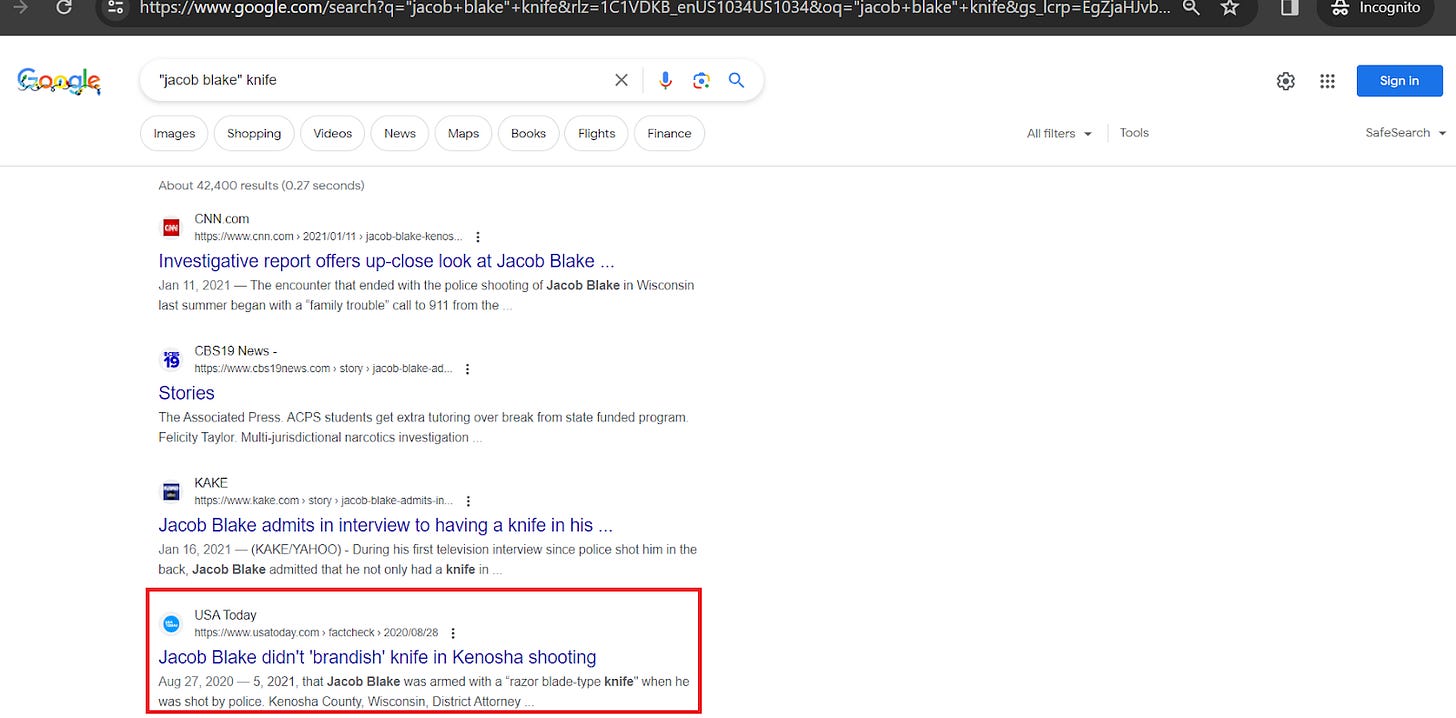

We’ll get there in a minute. But let’s first note that PolitiFact has been very effective in spreading this claim. If you Google what must be one of the most common search strings entered by curious news consumers hoping to better understand this incident — “Jacob Blake” + knife — in Chrome’s Incognito mode, you’ll see that it’s the fourth result, via USA Today’s habit of running PolitiFact content (and it’s the top result if you restrict your search to the PolitiFact.com domain).

With this headline, PolitiFact is, at this moment, actively misinforming the public about the Jacob Blake case. In late 2023. While its founder writes, with more than a glimmer of hope, that he and his ilk will be given more power to suppress “misinformation” in 2024 and beyond

Let’s dive a bit deeper into Litke’s actual fact-check. It was originally published on August 27, 2020, just days after the shooting, so he can certainly be forgiven for not having the full details. But the phrasing and framing stick out.

What we do know is that referring to Blake as “brandishing” appears to be an exaggeration.

Video of the shooting shows Blake walking around the front of the car with his back to officers and his left arm swinging at his side, grasping some object.

Brandishing is defined by Merriam-Webster as “to shake or wave (something, such as a weapon) menacingly.” That’s not what the video shows.

The phrasing is interesting here: How can we know what a video appears to show when, as was already clear when this fact-check was posted, the key moment is obscured by a car door?

PolitiFact notes that its policy, when evaluating the veracity of claims, is to place the burden of proof on the speaker. That’s fair. As of August 27, we didn’t know that Blake had probably swung a knife up toward the cop who shot him. But still: What is the point of so aggressively insisting that there was “no evidence” to support the claim of knife brandishing when so much was still unknown about the case? Why not just say “No one knows yet”? Perhaps more importantly, why not update the headline, which any internet expert knows is all that a large percentage of readers will read, once more facts are in?

Now, those who click through to the link will note that an update has at least been posted to the top of the article itself. So am I being whiny? I am not, because even this update goes out of its way to give readers the runaround.

Editor’s Note: Prosecutors revealed Jan. 5, 2021, that Jacob Blake was armed with a “razor blade–type knife” when he was shot by police. Kenosha County District Attorney Michael Graveley said as a result the officer who shot Blake could successfully argue self-defense, and therefore wouldn’t face criminal charges. That does not affect the rating for this item because ratings are based on what is known at the time. When this statement was made in August 2020, it was not clear what Blake was holding or when, given the grainy cell phone video and lack of detail released by police. [italics in the original]

This is a notably incomplete account of what happened. The Wray report makes it clear that whether or not a suspect is armed is not, alone, dispositive when it comes to disputes about the appropriate use of force: “For example, an 80-year-old person in a wheelchair, 20 feet away, threatening an officer with a knife probably provides an officer with different use of force options than a 25-year-old, not in a wheelchair, making the same threat.” Police officers subjected to proper scrutiny cannot shoot an 80-year-old person in a wheelchair simply because he or she is “armed,” but in the Blake case Sheskey and his colleagues all claimed they had valid reason to believe Sheskey was about to get stabbed by Blake — as is noted at the bottom of the very Journal Sentinel article the update links to.

Why would PolitiFact include none of this information, instead posting what feels like the least informative update possible? It’s baffling, but it fits what feels like a pattern of selectively leaving out information that would complicate the most strident progressive claims about the Blake and Rittenhouse cases.

While PolitiFact, which after all has finite resources, published only a limited number of items on Blake and Rittenhouse, the aforementioned one was written in response not to claims emanating from some major public figure, but “a widely shared Aug. 26, 2020, Facebook post” of now-unknown provenance (since the link is dead). There was certainly right-wing misinformation about Kenosha, and of course PolitiFact should debunk it.

But countless prominent liberal politicians, pundits, and journalists claimed that Blake was “unarmed” when he was shot, including CNN, Reuters, Politico, April Ryan, The Washington Post (that article, which had three Posties on its byline, was subsequently corrected), Adrian Wojnarowski and Mark Jones of ESPN (subsequently corrected), and Jake Tapper (chronically) — and that’s a partial list. Some of these claims came before the details were in (meaning the speaker didn’t know if what they were saying was true) and some came after (meaning they should have known what they were saying was false). Then-Democratic candidates Joe Biden and Kamala Harris both called for the officers to be charged not long after the shooting (and both spoke with Blake’s family), before anyone knew exactly what had happened, and to this day there’s widespread fury that no charges were filed, in large part because so many figures with giant platforms spouted off so much incendiary misinformation in the epistemically foggy wake of the shootings. Speaking of incendiary, there was also, you know, the small matter of the multiple deaths and perhaps $50 million in damage inflicted on Kenosha stemming directly from outrage over the shooting of Blake.2

In short, this is the very definition of a viral instance of liberal misinformation, and surely one that has had a bigger impact than a single now-deleted Facebook post. Guess what happens if you search the PolitiFact domain for any coverage of “Blake” and “unarmed” that seeks to dispel the widespread notion he was weaponless? Bupkes.

There are some hints as to the origins of this blind spot in Bill Adair’s Nieman Lab article. First, he claims that the rise of online fact-checking “worked — sort of. Fact-checking became a Thing, foundations kicked in money, and some politicians (um, mostly Democrats) became more cautious about what they said and did.” He offers no evidence to support the idea that “mostly Democrats” changed their behavior as a result of a bunch of nerdy websites. I think it’s much more likely, based on what we know about how hard it is to change behavior and to pop the bubbles of partisanship and epistemic closure, that fact-checking has had no measurable effect on politicians’ behavior (even if it’s important and useful in its own right, when done correctly just for setting the record straight). Though I’m also open to other theories: maybe Democrats know the fact-checkers are left-leaning and therefore don’t have to worry as much about getting fact-checked, meaning they can lie more, and/or maybe Republicans know fact-checkers are seen as left-leaning and don’t care if they get fact-checked, so they can lie more, blah blah blah. The point is, if the universe made any sense, “founder of a fact-checking organization making a totally unfounded claim about the causal impact of fact-checking and offering no evidence for it” would rip open a hole in the very fabric of reality.

Adair notes that “Another problem is that fact-checks aren’t reaching the people who need them the most. Although this hasn’t been studied as directly as the location of fact-checkers, it’s pretty clear from the research that Republicans distrust political fact-checking.” Huh, I wonder why that is? Adair doesn’t make this argument directly, but I think this connects to the idea that misinformation needs to be actively “suppressed.” If those dang conservatives won’t come to us to be set straight — if they continue to think Kyle Rittenhouse was acting in self-defense — then we’ll have to find them where they’re at by suppressing news before it can even get to them!

It’s all a bit dystopian and frustrating, and I could snark about it forever. But the overall point is, no, I don’t trust Bill Adair and PolitiFact to decide, for conservatives or for me or for anyone else, what is “misinformation” and should therefore be “suppressed.” Not until they prove that they themselves have a firmer and less ideologically blinkered handle on these concepts.

Questions? Comments? Thorough “fact-checks” of this newsletter that miss the point entirely? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Image: KENOSHA, WISCONSIN - NOVEMBER 21: Activists protest the verdict in the Kyle Rittenhouse trial on November 21, 2021 in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Rittenhouse, an Illinois teenager, was found not guilty of all charges in the fatal shootings of Joseph Rosenbaum and Anthony Huber and for the shooting and wounding of Gaige Grosskreutz during unrest in Kenosha, Wisconsin that followed the police shooting of Jacob Blake in August 2020. (Photo by Jim Vondruska/Getty Images)

During the trial, whatever air was left in the prosecution’s tires was violently expelled when Grosskreutz acknowledged on the witness stand that yes, he was pointing the gun at Rittenhouse when he was shot.

I’m sure some people are going to be mad that I’m linking to Fox News and to what appears to be a right-wing journalist in this paragraph. I don’t know what to tell you. In this particular instance, I think the journalists in question are correct. You know what would be a great source to link to for a one-stop shopping article about all the liberal misinformation about Jacob Blake? PolitiFact.com.

As an ardent and unimpeachable critic of police violence, I have no qualms admitting Jesse is absolutely correct here.

I really appreciated your reporting in Kenosha at the time. I felt like I was going insane because all my friends would post random stuff about it and every time I tried to verify I’d hit a brick wall.