Why Did “On The Media” Stoke The Moral Panic Against Innocent New York Times Journalists Rather Than Investigate It?

Journalism and media criticism both require skepticism

I’m only able to do what I do because of my paying subscribers. If you find this work interesting or useful, please consider becoming one, or buying a gift subscription for a friend. This will unlock a lot of extra, paywalled content.

Thanks!

I’m still frustrated that so many journalists participated in a deeply unfair smear campaign against a group of very talented reporters at The New York Times earlier this year. I’d mostly gotten over it, but I was re-agitated by a segment about the controversy On the Media aired this week, which offers a tidy how-not-to lesson in contemporary media criticism.

This post will be long and I’m going to break it up into two sections. The first will be a rundown of the blowup itself and a listing of the major false, apparently false, and misleading statements contained in the open letter that sparked this moral panic. If you’ve already been following OpenLetterGhazi closely, you can skip that section and jump down to the second one, where I criticize the OTM segment.

The Open Letter Was Really Dishonest

On February 15 of this year, a group of journalists, writers, and celebrities who have contributed to The New York Times released an open letter, which you can read here, accusing the Times of bigotry and ignorance in its recent coverage of transgender issues, particularly issues involving transgender youth. It was signed by hundreds of folks who had contributed to the Times in the past as well as, according to the organizers, “20,000 media workers, subscribers, and readers of the New York Times,” though those links are now all dead.

The smaller group that wrote the letter and organized its dissemination appears to be comprised entirely of journalists, and in a move that violates very basic and long-established rules about how members of my profession are supposed to conduct themselves, they coordinated directly with the activist organization GLAAD to ensure their letter would come out the same day GLAAD released its own letter, that one cosigned by celebrities and a bunch of other activist groups.

The cherry on top of this stunt was a truck that GLAAD parked outside the Times building that attempted to raise awareness of the transphobia allegedly transpiring therein via a billboard displaying messages like “Dear New York Times: Stop Questioning Trans People’s Right to Exist & Access to Medical Care.” (It’s demoralizing I even need to say this, but at no point has anything printed in the Times in recent memory “Question[ed] Trans People’s Right to Exist.”)

I call it a “stunt” because this whole thing was ridiculous. And not just ridiculous — the journalists’ letter, which of course we should hold to a higher standard than GLAAD’s own, was a deeply unfair hatchet job which denigrated, by name, a number of Times journalists who have done an admirable job covering a very complicated set of issues: Emily Bazelon, Azeen Ghorayshi, and Katie Baker. If you read the letter, you will see shockingly few accurate, substantive complaints about any of their work, with a single, minor exception that the Times has since addressed (I’ll get to it). What you’ll find plenty of, on the other hand, are outright lies and apparent lies as well as some real slippery language that wouldn’t pass muster with any fair-minded adult newspaper editor. The whole thing was so demoralizing, especially the fact that the letter was signed not just by usual-suspect Twitter cranks — the types who seem to do very little but organize open letters — but also by talented journalists who I respect and, in some cases, worked with at New York Magazine.

Katie Herzog and I discussed this controversy in an episode of Blocked and Reported we recorded shortly after this circus was unleashed, but the best and most thorough debunking came from The Washington Post’s Eric Wemple, who is one of the smartest media critics in the business. On June 15, the Post published his more than 3,500-word treatment of the saga. In it, Wemple concluded that the Times coverage of these issues has been consistently high quality. On the other hand, “The contributors’ letter falls short of these standards, and the rolling billboards [from GLAAD] are no better. That weakness masks the real purpose of the effort against the Times, which is to discourage in-depth stories on trans health care or put an end to such coverage altogether.”

Wemple is exactly right, and some of us who have been criticized for our coverage of the youth trans debate have been saying this for years. The goal here is simply to render the very real controversies over youth gender issues, and particularly youth gender medicine, absolutely un-coverable for respectable journalists who refuse to restrict themselves to the production of feel-good, activist-approved pablum. You simply cannot treat youth gender medicine as the complicated, controversial issue that it is — cannot treat it journalistically — unless you’re willing to endure severe public attacks on your reputation (as the Times journalists learned).

In a saner media landscape, Wemple’s thorough evisceration would have put these unfair claims to bed for good. Alas, that hasn’t happened. A lot of people in media, including plenty with big microphones, continue to run around acting as though the Times has seriously erred in its coverage of transgender issues, despite a notable dearth, all these months later, of any proven instances of journalistic wrongdoing remotely worthy of a rolling-billboard response.

So I think it’s worth debunking every major unfair claim in the letter, and that’s what I’m going to do here.1

—The authors of the open letter argue that “Katie Baker’s recent feature ‘When Students Change Gender Identity and Parents Don’t Know’ misframed the battle over children’s right to safely transition. The piece fails to make clear that court cases brought by parents who want schools to out their trans children are part of a legal strategy pursued by anti-trans hate groups.” (All the links to the Times stories are mine — while the open letter is drenched with links, the authors don’t appear to have linked directly to any of the articles they criticized.)

This is a lie.

All it takes to see that it’s a lie is to actually read Baker’s piece:

Since 2020, at least 11 lawsuits alleging that these policies violate parental rights have been filed against school districts by parents who are represented by conservative legal groups, such as the Alliance Defending Freedom, an organization with a long history of backing cases targeting the rights of gay and transgender people.

Three parents, all self-described liberals, told The Times that support groups had connected them with a legal group affiliated with the Alliance, called the Child and Parental Rights Campaign, which was founded in 2019 with the mission of defending children and parents against “gender identity ideology,” according to its nonprofit disclosure forms. Its president has spoken at conferences about the “existential threat to our culture” posed by the “transgender movement.”

Could Baker have made it any “clear[er] that court cases brought by parents who want schools to out their trans children are part of a legal strategy pursued by anti-trans hate groups”? The authors of the letter are lying, full stop. And what’s disturbing is that after Wemple contacted a group of them to ask if they would correct this clear error, they refused to. “The published version of the story does not expand upon how that agenda might inform the legal cases in question,” one of the co-authors emailed Wemple and the colleagues who helped him prepare his article. “Name-checking the threat alone is not providing adequate context, especially as the extent of anti-trans coordination becomes even clearer.”

This sort of goalpost-moving, coming as it does in the context of a journalist being bashed by name, is deeply sleazy. Worse, I haven’t seen any indication that a single signatory has removed his or her name from the letter since Wemple’s article came out. Keeping your name on an open letter after you have discovered that it contains a false claim against someone is as straightforward a violation of basic journalistic principles as you’ll find. I really think the signatories should be pressed on this.

—The authors argue that “[Emily] Bazelon quoted multiple expert sources who have since expressed regret over their work’s misrepresentation” in her excellent June 2022 New York Times Magazine article on the debate over youth gender medicine. This appears to be false.

The link is to an 80-minute podcast interview with Jules Gill-Peterson, a Johns Hopkins University historian who is not quoted in Bazelon’s piece. So right off the bat, it’s unclear how Bazelon could have possibly misrepresented the work of a scholar whose name she didn’t mention.

It’s not a good sign if, instead of providing direct and clear evidence for a claim, someone instead points you to an 80-minute podcast without specifying what, exactly, you should be listening for. To their credit, Wemple and his colleagues actually listened to the podcast in its entirety. They found no evidence there to suggest Bazelon misrepresented anyone, and a follow-up claim by the open letter authors — one they didn’t include in the letter itself — didn’t pan out, either:

When the Erik Wemple Blog pointed out this disconnect [over Gill-Peterson’s absence from the article], the letter writers responded that the podcast made clear that Bazelon’s story “rests on a factually incorrect framing of Jules Gill-Peterson’s work.”

The podcast did make clear that Gill-Peterson takes umbrage at how Bazelon approaches WPATH’s historical role in transgender care. When we asked whether she claims that Bazelon misrepresented her work, Gill-Peterson responded with a critique citing alleged omissions and other problems with the story.

As for other allegations of misrepresentation, the letter writers mentioned Beans Velocci, a historian at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in sex, gender and sexuality. “The Battle Over Gender Therapy” summarized and quoted from a journal article written by Velocci. When we asked Velocci whether that reference misrepresented their work, they declined to respond directly and passed along a link to another nearly 80-minute podcast in which they criticized Bazelon’s story. “My name and expertise was used to do anti-trans violence, so that sucks,” Velocci said in the podcast. The Times says that it “accurately” cited Velocci’s work in order to clarify “WPATH’s problematic origins in the 1950s and 60s, when doctors made biased decisions to exclude some adult patients from receiving care for medical transition.”

In a side-by-side examination of Velocci’s journal article and Bazelon’s story, we found no misrepresentations.

—The authors accuse Bazelon of failing to identify Grace Lidinsky-Smith, a prominent detransitioner, as “the President of GCCAN, an activist organization that pushes junk science and partners with explicitly anti-trans hate groups.” There is no evidence GCCAN has ever partnered with even a single “explicitly anti-trans hate group[].”

I think the Times probably should have noted Lidinsky-Smith’s affiliation, but it’s a pretty big deal for the open letter authors to accuse her of having partnered with “explicitly anti-trans hate groups,” and they have provided no evidence to back up that claim. What are the groups in question? No one seems to know.

I asked Lidinsky-Smith via email. “I was actually just wondering this myself,” she replied. “Because the letter didn’t say. . . I officially did something with FAIR, which people say is anti-trans, and also I think we got in some trouble for being in email contact with someone from SEGM. But I don’t know specifically who they were talking about and I don’t even know who I would ask.” Suffice it to say that nothing she is saying remotely justifies the claim made by the open letter authors — neither the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism nor the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine is an “explicitly anti-trans hate group” by any stretch of the imagination, and according to Lidinsky-Smith, there was no “partnership” with SEGM, the gender-related of the two, anyway.

I reached out to the contact address listed on the NYTLetter.com website to ask about this and didn’t hear back. Wemple didn’t respond to a Twitter DM inquiring about this, either. (This was one of the few aspects of the letter his otherwise thorough article didn’t address directly.)

—The authors of the open letter badly misrepresent the present state of and evidence for youth gender medicine.

They write: “As thinkers, we are disappointed to see the New York Times follow the lead of far-right hate groups in presenting gender diversity as a new controversy warranting new, punitive legislation. Puberty blockers, hormone replacement therapy, and gender-affirming surgeries have been standard forms of care for cis and trans people alike for decades.”

As a thinker, I’m having trouble coming up with any instance in which the Times has presented “gender diversity” per se, as “a new controversy warranting new, punitive legislation.” Rather, the Times has covered a pair of in-fact-brand-new controversies: what the assessment process should look like prior to minors being granted access to youth gender medicine as demand for these treatments skyrockets (Bazelon’s work, and some of Azeen Ghorayshi’s), and whether schools should offer minor students who come out as trans a policy of full, no-questions-asked gender self-ID without parental notification (Baker’s).

The second sentence above, describing the medical context, is deeply misleading. It’s only been in the past 15 years or so that children and teenagers have been given puberty blockers, hormones, and surgery in any significant numbers. The evidence base is so paltry that, as I noted this past April in UnHerd, WPATH itself declined to commission a systematic review due to the lack of decent studies, and the evidence reviews that have been commissioned by European health authorities have all concluded that there is massive uncertainty about these treatments. As an article in The Atlantic recently put it, “governments and medical authorities in at least five countries that once led the way on gender-affirming treatments for children and adolescents are now reversing course, arguing that the science undergirding these treatments is unproven, and their benefits unclear. . . . [I]n Finland, Sweden, France, Norway, and the U.K., scientists and public-health officials are warning that, for some young people, these interventions may do more harm than good.”

So the “standard forms of care” phrasing is quite misleading in this context — surely readers will interpret it as something like Experts agree that there is sound evidence for these treatments. That couldn’t be further from the truth.

The mention of cisgender people having accessed blockers and hormones for decades, meanwhile, is completely irrelevant; of course research derived from children taking puberty blockers for precocious puberty, or from adult women taking estrogen to treat menopause symptoms, cannot provide us with sufficient evidence about whether it’s wise to use these treatments in entirely different medical settings with entirely different treatment goals.

—The authors make a prima facie ridiculous argument about conservative legal briefs.

They write:

The natural destination of poor editorial judgment is the court of law. Last year, Arkansas’ attorney general filed an amicus brief in defense of Alabama’s Vulnerable Child Compassion and Protection Act, which would make it a felony, punishable by up to 10 years’ imprisonment, for any medical provider to administer certain gender-affirming medical care to a minor (including puberty blockers) that diverges from their sex assigned at birth. The brief cited three different New York Times articles to justify its support of the law: Bazelon’s “The Battle Over Gender Therapy,” Azeen Ghorayshi’s “Doctors Debate Whether Trans Teens Need Therapy Before Hormones,” and Ross Douthat’s “How to Make Sense of the New L.G.B.T.Q. Culture War.” As recently as February 8th, 2023, attorney David Begley’s invited testimony to the Nebraska state legislature in support of a similar bill approvingly cited the Times’ reporting and relied on its reputation as the “paper of record” to justify criminalizing gender-affirming care.

If the Times writers in question had made factual errors that subsequently found their way into the courts and affected legal rulings, that would be one thing. But that’s not what the open letter authors are alleging — or if they are, they have provided no evidence that any of these articles contain any meaningful errors. Rather, the argument seems to be that even if a journalist’s work is true, if it is subsequently used for nefarious purposes by some other party, the journalist is responsible.

No journalist with a brain actually believes this. It’s an impossible —impossible — standard to apply consistently. It’s like saying that if a journalist covers police abuse aggressively but fairly, and some nutjob reader subsequently murders a cop and was found to have read the journalist’s article, the journalist is partly culpable for the murder. This is a ridiculously unfair standard to hold journalists to, as I’ve previously noted. Were it widely adopted, journalism on any remotely controversial subject would cease to exist.

—Even the one accusation leveled by the open letter authors that the Times agreed to address was made in a misleading manner.

The authors argue that “Emily Bazelon’s article ‘The Battle Over Gender Therapy’ uncritically used the term ‘patient zero’ to refer to a trans child seeking gender-affirming care, a phrase that vilifies transness as a disease to be feared.” This is missing a tremendous amount of context, perhaps most importantly that Bazelon was referring to the very first young person a famous team of Dutch clinicians ever put on puberty blockers.

That part of her story originally read:

[Dutch clinician and youth gender medicine pioneer Peggy] Cohen-Kettenis helped establish a treatment protocol that proved revolutionary. Patient Zero, known as F.G., was referred around 1987 to Henriette A. Delemarre-van de Waal, a pediatric endocrinologist who went on to found the gender clinic in Amsterdam with Cohen-Kettenis. At 13, F.G. was in despair about going through female puberty, and Delemarre-van de Waal put him on puberty suppressants, with Cohen-Kettenis later monitoring him. The medication would pause development of secondary sex characteristics, sparing F.G. the experience of feeling that his body was betraying him, buying time and making it easier for him to go through male puberty later, if he then decided to take testosterone. Transgender adults, whom Cohen-Kettenis also treated, sometimes said they wished they could have transitioned earlier in life, when they might have attained the masculine or feminine ideal they envisioned. “Of course, I wanted that,” F.G. said of puberty suppressants, in an interview in “The Dutch Approach,” a 2020 book about the Amsterdam clinic by the historian Alex Bakker. “Later I realized that I had been the first, the guinea pig. But I didn’t care.”

So first of all, there’s simply nothing in the sentence in question that could possibly justify the open letter authors’ interpretation that Bazelon was using the phrase to “vilif[y] transness as a disease to be feared,” especially in light of the fact that Bazelon later interviews F.G., who appears to have benefited from the treatment and to be doing well. In context, the claim doesn’t make any sense. Secondly, after the open letter dropped, Reason’s Billy Binion quickly got in touch with Bakker, and two days later he published a piece in which he explained that Bakker himself referred to F.G. as “patient zero” in his book and said he didn’t think it was offensive. Third, the Times did eventually change this language to “The first patient” — what the contested phrase obviously meant all along — and in the editor’s note that was posted when this change was made, the magazine notes that F.G. also referred to himself as “patient zero” to Bazelon.

Now, would Bazelon and the Times Magazine have saved themselves some trouble by including this context, given that, as Binion notes, the term patient zero does have an ugly, AIDS-era history? Yes. But should the open letter authors have updated their letter once they had this explanation, and once they found out that F.G. himself used the term — or, better yet, inquired with the magazine before speculating in such an inflammatory manner about the meaning of “patient zero”? Of course! And of course, they didn’t. They are favoring their own, rather dark interpretation of Bazelon’s word choice over the feelings of the actual person being referred to!

***

So those are the main claims in the letter. There aren’t a lot of them, because its length is padded out by about a third with hundreds of words about the Times’ history of missteps on LGBT issues that have nothing to do with the present debate (while I haven’t checked these claims, I would be very careful about taking them at face value, given the authors’ demonstrable struggles communicating honestly and accurately about the present). And almost every one of them is a lie, a likely lie, or stripped of vital context.

There’s some tidy symbolism to the fact that the Times contributors responsible for this letter coordinated with GLAAD, an activist group that has vehemently attacked journalists for covering this subject (myself included). Because that’s exactly what so many journalists and activists are now calling for: journalists to act as PR hacks for activist organizations. To be sure, journalists should take reasonable activists’ claims into account when learning about and reporting on a subject. All else being equal, if you write about trans issues, you should touch base with GLAAD and/or HRC and/or similarly minded organizations, since they are the leaders in this area.

But that doesn’t mean you have to accept what they say. In fact, if you do accept what they say in a mindless or parrotlike fashion, you’re no longer performing journalism. You should probably leave this field, in fact, and go work for one of the many rights organizations that could use the PR assistance. You’ll be better paid there, and ideally the slot you vacate will be filled by one of the perhaps tens of thousands of competent, principled journalists who have been laid off during our industry’s implosion.

And make no mistake: when it comes to youth gender medicine, some of these activist organizations are far too off the rails to have earned any reflexive deference from journalists. Here’s one of the more forehead-smacking parts of Wemple’s article:

Plowing through all the coverage takes time, and a mastery of the ins and outs can be elusive. When we asked GLAAD’s [president, Sarah] Ellis to cite particular objections to Bazelon’s piece, for example, she paused before saying, “I think the overall framing of it, truly. I think you’re asking for a little more detail than I can give at this moment.” (A GLAAD spokesperson later sent along concerns that largely mirrored those of the contributors’ letter.)

As we know, the letter itself contains almost no substantive critiques of Bazelon’s work, and even the complaint that caused her magazine to change the “patient zero” phrasing was, in full context, a stretch. By the time of Wemple’s article, GLAAD had had months to figure out exactly why the Bazelon article, which was more responsible for the uproar than anything else the Times had published on trans issues, warranted such vociferous attacks — remember, there was a truck! There’s fundamentally still no there there. It doesn’t matter how many billboards GLAAD commissions or how inflammatory its press releases get. The truth matters, and the truth is not on GLAAD’s side here.

Journalists, if they are to perform their basic duties as journalists, must recognize that.

Enter On the Media (Unfortunately)

Under normal circumstances, it would be good news for the hypothetically venerable WNYC media criticism show On the Media to decide to look into this issue. Who better to cut through all the smoke and noise and sift the fair complaints from the unfair ones?

Unfortunately, On the Media — a show I used to love and listen to weekly — is a desiccated shell of its former shelf. To say that its credibility has cratered in recent years would be like saying that Donald Trump appears to be facing some minor legal challenges. To take one of many examples, the last time I wrote about the show, it was in part to point out that one of its guests, Jo Yurcaba of NBC News, argued that reporters who cover the youth gender medicine debate were partly responsible for the mass shooting that had just taken place at an LGBTQ nightclub in Colorado Springs. Even claiming that youth gender medicine is controversial, Yurcaba argued, “can be really troubling and dangerous.” Dangerous! I’m sorry, but this is deranged and completely disgraceful. Those are the only words for it. And host Brooke Gladstone barely pushed back at all.

Things. . . haven’t really improved. This week’s episode is mostly given over to a 42-minute segment following up on the open letter and the Times’ reaction to it. It’s hosted by OTM correspondent Micah Loewinger, and it’s clear that neither he nor any of the producers engaged in much due diligence with regard to the allegations leveled in that letter or the realities of the youth gender medicine debate. Over and over and over, the segment repeats and re-amplifies the false and questionable claims contained in the letter with very little skepticism or pushback. While the segment does include an interview with Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein, his voice is mostly used to represent the “other side” in the classically superficial style of subpar journalism everywhere — the producers make no independent effort to really get at the truth, and they clearly default to the stance that the open letter authors’ claims are true as written, with just about every editorial choice, big and small, pointing in that direction.

For example, the segment suffers from a jarring absence: any acknowledgement of the criticisms of the letter. Wemple’s article — a major effort to investigate the open letter that found major factual problems with it, and which was published in the second-most important newspaper in the country — goes completely unmentioned. Listening to this segment as an unfamiliar newcomer to the controversy, you’d come away thinking that the open letter contained accurate criticisms of the Times’ coverage of trans issues — that is, you’d come away completely misinformed.

(I should note that OTM is far from the only offender here. Wemple’s article notes that “For a mediasphere already saturated with media criticism, the [open letter controversy and subsequent internecine Times chaos] gained extraordinary traction, launching a cavalcade of follow-up stories from NPR, WNYC, the Guardian, Vanity Fair, the Daily Beast, Semafor, Vox and others.” Not a single one of those articles or segments noted any of the false or questionable claims in the letter, and I’m not aware of any mainstream treatment of the controversy that did so prior to Wemple’s investigation. This is a very low bar to trip over.)

I’m not going to go through every instance of ridiculousness in this deeply irresponsible segment, but let’s cover some “highlights,” relying on the transcript provided by WNYC. (Note: my copy editor cleaned up the transcript here and there for legibility, where their style is inconsistent, and where the intended meaning was affected; she otherwise left it the way OTM transcribed it.)

Toward the top:

Micah Loewinger: We’ve been working on a piece about this since March, and granted, it’s only been about five months, but we wanted to see if the fallout from the letters had had any noticeable effect on the coverage of trans issues at The Times. I spoke to Jules Gill-Peterson, a historian at Johns Hopkins University and the author of Histories of the Transgender Child. She signed the contributor’s letter which points to how Times’ articles have been cited in recent anti-trans legislation.

You would think, given that Gill-Peterson signed a document claiming that she was misrepresented by Bazelon, that Loewinger would ask her about that. How was she misrepresented? Perhaps because the answer appears to be “she wasn’t” — an answer that calls some of the letter’s credibility into question, not to mention Gill-Peterson’s — the segment simply ignores that aspect of it. It wasn’t a matter of being squeezed for time, as OTM gives Gill-Peterson plenty of minutes to discuss all sorts of subjects tangential to the Times controversy. And yet there’s nothing about the one allegation in the letter that specifically concerns her. It’s a bizarre and telling oversight.

Next:

Micah Loewinger: One of the common criticisms that I saw of Emily Bazelon’s piece was some of the language she chose to use, including the term patient zero to refer to a trans child seeking gender-affirming care. That’s a phrase with a really fraught history that some perceived was vilifying transness as a disease to be feared.

Jules Gill-Peterson: One of the key concepts that has trickled into a more respectable, ostensibly academic arena is a notion of social contagion, the idea that there are more, particularly more trans young people because it’s somehow like a contagious identity. One of the origins of this notion is a 2018 paper by a social scientist named Lisa Littman, who coined this very pseudoscientific term that has since been loudly critiqued and debunked over and over again of rapid onset gender dysphoria.

The notion that when children or youth come out to their parents, they suddenly want to transition, and maybe the obvious reason why is because they’ve been thinking about it for a long time and now have just told their parents. The notion of a patient zero creates this disease model where being transgender is a negative thing that is spreading too fast through the population, and therefore, it’s appropriate to restrict it.

Also, patient zero just harkens [sic] back to that was a term brought about early on in the AIDS epidemic that was really used to vilify gay men as if they were particularly responsible for and had some sort of moral responsibility for this virus and its spread, which is a complete distraction from the failure of government and public health to actually do anything to mitigate the spread or research HIV early on, in part because people didn’t care or even welcome[d] the death of gay men. It’s just really alarming to use language like that, and for what purpose?

One more time: it defies all logic and basic reading comprehension to believe that the usage of patient zero in this case was intended to spark any of the associations Gill-Peterson is referencing here. Again, the original language read “[Peggy] Cohen-Kettenis helped establish a treatment protocol that proved revolutionary. Patient Zero, known as F.G., was referred around. . . ” The meaning of “Patient Zero” jumps off the page, whether or not you’re sympathetic to the idea that the article shouldn’t have used this phase: it simply means “the first patient to get this treatment.”

And at the risk of repeating myself, we now know exactly why Bazelon used this language to describe F.G. — Alex Bakker, the historian who wrote about him, called him that, as did F.G. himself! Instead of quickly resolving this minor issue, which was fundamentally a matter of the article failing to include a five-word parenthetical, OTM gives Gill-Peterson a minute and a half to toss out various insinuations uncoupled to any evidence that Bazelon’s word choice was motivated by nefarious motives, only then bringing in the voice of Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein, who provides the correct context.

OTM is making these production choices intentionally: it is seeking to fuel the idea that there’s some evidence Bazelon and the magazine did something wrong here, even though the facts suggest, at worst, a lack of attention to the possibility of people being offended by a choice that was clearly justifiable in full context.

Moving on: almost every poorly reasoned, left-of-center treatment of youth gender medicine will eventually reference The Left-Handedness Graph, and of course this episode of On the Media is no exception.

Here’s how the left-handedness graph is usually presented in this context:

The show then plays a clip from John Oliver, who ran a truly abysmal segment on this subject late last year that we discussed on BARPod:

John Oliver: As for the rapid rise in kids identifying as trans. . .

Micah Loewinger: John Oliver addressed this on his show Last Week Tonight.

John Oliver: As the writer Julia Serano was [sic] pointed out, when you look at a chart of left-handedness among Americans over the 20th century, you see a massive spike when we stopped forcing kids to write with their right hand, and then a plateau. That doesn’t mean everyone became left-handed or there was a rapid onset southpaw dysphoria. It means people were free to be who they were.

Jules Gill-Peterson: This is a point that trans folks have made for a long time. That graph has been shared for years, and part of what’s so helpful about it is it just de-dramatizes everything. Being left-handed is no longer considered much of a big deal. It’s just part of the variation of human life. I think there’s some real limitations to that notion because part of what it does, oddly enough, is reinforce that the idea here is just we have to tolerate or accept that people exist, period. This is actually a very popular form of trans inclusion.

Here, via SEGM, is a graph of referrals at one famous United Kingdom gender clinic:

If you click that link they’ve got a couple other, similar graphs from gender clinics elsewhere, too. And we know that in the States, there’s been a huge uptick not only in clinic referrals, but in youth gender dysphoria diagnoses: Reuters, relying on a first-of-its-kind analysis of insurance claims from the health technology company Komodo Health Inc., reported last year that “at least 121,882 children ages 6 to 17 were diagnosed with gender dysphoria in the five years to the end of 2021. More than 42,000 of those children were diagnosed just last year, up 70% from 2020.”

As a wiser John Oliver might put it, it’s utterly daft to claim that the left-handedness graph proves anything about these facts and figures. When all you have is a graph that has suddenly gone up, you really don’t know what it means. Sometimes, yes, the phenomenon in question follows the rule of left-handedness, a phenomenon which in the absence of coercion has a very clear base rate, meaning things will settle at the new, higher level. But other times, things are more complicated than that.

Serano, Oliver, and the others adopting this analogy are conflating handedness, which can be very easily “diagnosed” with objective measures, with the much fuzzier, more controversial, and contested concept of youth gender dysphoria, the diagnostic criteria of which are largely subjective. For the purposes of youth gender medicine, what matters is how often kids are showing up at gender clinics with suspected GD, and how often they’re being diagnosed with it. That’s what’s caught the notice of so many observers — skyrocketing referrals to youth gender clinics all over the U.S. and Europe, leading to a lot of graphs like that one up there.

Unless youth gender dysphoria is somehow unlike every single other psychological diagnosis ever conceptualized, surely it does not exist in some sort of pure Platonic realm where human cultural messiness has zero impact on who thinks they (or their children) have it, on how likely adult clinicians are to diagnosis it, and so on. There’s a lot of history here: every era of psychology and psychiatry has its fads. We know from plenty of past instances that “Diagnosis du jour” is a thing — sometimes doctors or therapists get really excited about a trendy condition and start diagnosing it a lot, when during another period, presented with the exact same symptoms, they would have attributed them to some other disorder (or no disorder at all).

Even on the subject of youth gender dysphoria, where a tremendous number of questions remain unanswered, there are hints of these forces at work: The Cass Review, for example, referenced the tendency toward “diagnostic overshadowing” at a major British clinic — “many of the children and young people presenting have complex needs, but once they are identified as having gender-related distress, other important healthcare issues that would normally be managed by local services can sometimes be subsumed by the label of gender dysphoria.”

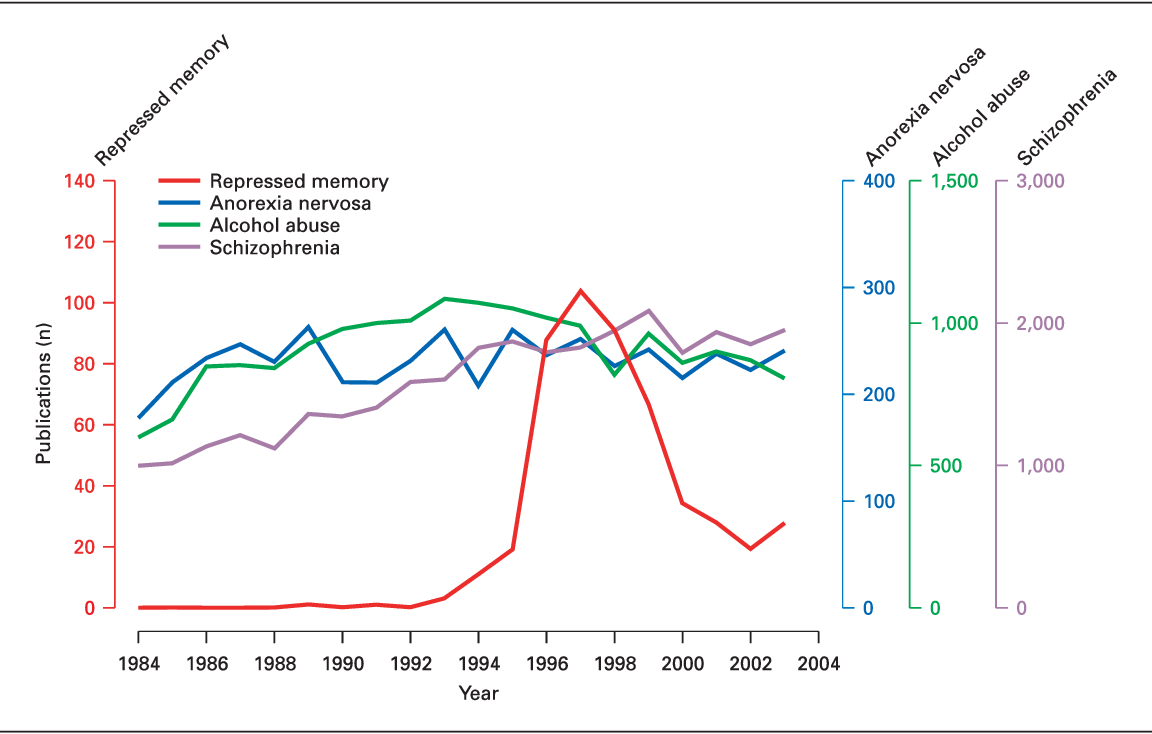

It’s not like we don’t have precedent for this: there was a period from the 1980s into the 1990s when, relatively speaking, a ton of people were being diagnosed with what used to be called “multiple personality disorder” but which is now called “dissociative identity disorder,” or DID. Sometimes, through shoddy therapeutic practices, vague and common symptoms would be interpreted as evidence of repressed past trauma, which would lead to the emergence of “alters,” or alternate personalities residing in a single brain. Or otherwise troubled people would decide, on their own, that they had multiple personalities, and then go to clinician-enthusiasts who validated that belief in a fairly knee-jerk and careless manner, without much careful differential diagnosis. Belief in “recovered memories” led to many miscarriages of justice, as parents and caregivers were falsely accused of heinous (and, in many cases, clearly unlikely) acts.

These days, recovered memories are much more controversial, as is the concept of DID, which appears to be much less frequently diagnosed (Scientific American ran a pretty bad article on the subject back in June). There’s solid evidence the ideas of recovered memories and multiple personalities constituted a fad, and by the end of the twentieth century, the cottage industry of clinicians and researchers whose work relied on such concepts was collapsing in on itself.

I couldn’t find good data on the rates of diagnoses MPD/DID, but I did find this related graph on research interest in repressed memory, captioned “Annual numbers of publications regarding repressed memory (dissociative amnesia) from 1984 to 2003 compared to three reference disorders: anorexia nervosa, alcohol abuse, and schizophrenia”:

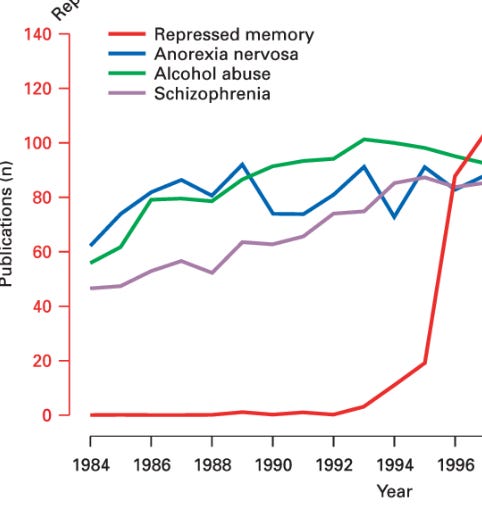

In 1997 or so, the graph for research interest in repressed memories would have looked like this:

If Expert A insisted this whole repressed memory thing was an ill-considered fad, Expert B could reply that no, research interest was just catching up to the reality that repressed memory is a vitally important thing to study, because countless people have as-yet-unlocked repressed memories of past sexual abuse and other forms of injustice that need to be discovered for society to truly grapple with child sexual abuse.

Today, we know that Expert A would have been the more correct of the two — we have access to the full graph and can see that this was, indeed, a fad (not that there aren’t still true believers and clinicians who would disagree with my assessment). But the point is that if you have access only to the first part of the graph, you just can’t know for sure!

I’m not saying this is exactly what’s happening with youth gender dysphoria; I’m saying that intellectual humility, coupled with an understanding of how complicated psychology and psychiatry are and how frequently these fields veer off course, demands that we not overclaim. No one knows for sure why there’s been a massive (in some cases exponential) increase in youth GD referrals and diagnoses, but it’s quite unlikely that it’s as simple as “Well, now the infallible experts, the infallible parents, and the infallible kids have simply identified all the young people who really have GD.” The left-handedness graph proves exactly nothing on its own. It isn’t clever and it isn’t a good analogy. (Of course, I could level the same charge at those who confidently claim that the entire uptick is due to “rapid onset gender dysphoria,” or whatever — it’s the same error of overconfidence, just pointing in the other direction.)

(Update, 8/18/2023: I should have included a link to Dave Hewitt’s convincing takedown of this meme from this past November. Read that if you’d like to go into more depth on the myriad ways the youth GD/handedness comparison is broken beyond repair.)

After the obligatory handedness reference, Loewinger and Gill-Peterson spend about four minutes talking about laws intending to ban drag performances, why they’re bad and unconstitutional, why Ron DeSantis gutting AP African American Studies in Florida is bad, and why (again, via John Oliver) Gill-Peterson thinks Chris Rufo, who is also bad, is partially responsible for both the anti-CRT and the anti-transgender conservative moral panics.

By this point, the astute listener might be wondering when, in this well-padded segment, OTM will get to the part where the show truly digs into the claims contained in the Times open letter. Given that the segment took five months or so to produce, you’d think it would do so rather than spend so much time rehashing familiar gripes the American left has about the American right. But there’s just no real effort to actually probe and investigate the claims in the letter; again, not even a passing reference to Erik Wemple’s investigation. Plenty of time to remind everyone that Ron DeSantis is bad, not enough to make any progress toward establishing the truth of the matter at hand.

When OTM does get back to Bazelon’s article, it continues its role as PR flack for the letter writers:

Micah Loewinger: Jules Gill-Peterson believes The Times has seeded [sic] too much ground to right-wing attempts to distort the conversation. She and other Times contributors who signed the open letter point to an amicus brief filed by Arkansas’ Attorney General, who quoted from three New York Times pieces, including Emily Bazelon’s, in support of an Alabama bill that passed in April called the Vulnerable Child Compassion and Protection Act.

It takes OTM a minute and a half to lay out this complaint, and to bring back Jake Silverstein’s voice to point out that “these pieces were cited to show that there is a debate among providers about how to best perform gender care for minors,” that this is a true fact about the world, and that a journalist can’t be responsible for how their accurate reporting is then used by others. Again, it’s left as a she-said, he-said — Loewinger doesn’t ask Gill-Peterson to explain her position. Competent media critics would dig around here a bit and either try to interrogate what it would mean to blame a journalist for reporting something that is true, or marshal evidence that what Bazelon wrote wasn’t true; OTM doesn’t bother with either.

Having done approximately zero work to bring us any genuinely new information about the open letter’s claims, OTM then moves on to other critiques of Bazelon’s work made elsewhere:

Micah Loewinger: The frustration with the piece, as I understand it, is less with the facts that came out of the reporting, but with the framing, the choices, whose voices were featured prominently, what positions were featured prominently. For instance, the article quotes extensively from parents involved in a group called Genspect, an organization that opposes gender-affirming care for young people. Kit O’Connell, a journalist and editor at The Texas Observer, felt that the article presents them only as a concerned group of parents, rather than activists trying to skew the conversation.

Kit O’Connell [sic — this should read Jake Silverstein]: We’ve heard this criticism about not identifying Genspect. Some of the people who’ve criticized Emily’s story have wanted us to refer to Genspect as a hate group. We can’t say that without evidence. We can characterize groups up to a point unless we’re going to dedicate reporting time to investigating a particular group. We can’t characterize it a certain way without evidence.

This is yet another point at which On the Media would have been better served checking the claims of Bazelon’s critics than simply amplifying them. O’Connell’s argument in her Texas Observer article, which is headlined “There Is No Legitimate ‘Debate’ Over Gender-Affirming Healthcare” (because of course it is), went as follows:

Bazelon’s article quotes extensively from parents involved in a group called GENSPECT, an organization that opposes gender-affirming care for young people. Some members quoted support banning transition for anyone under 25, which has become a mainstream Republican position. Bazelon noted on Twitter that the group has engaged in anti-trans activism. The article, however, presents them only as a concerned group of parents, ignoring this vital context.

“When you find yourself, in the final story, repeating the talking points of anti-trans activists without criticism, without context, then even if you don’t have an agenda, you’re advancing the agenda of the people you’re platforming,” said Heron Greenesmith, an attorney and senior research analyst at Political Research Associates who specializes in tracking how the media covers transgender people. “Emily Bazelon did a really great job of replicating their anti-trans talking points in the paper of record.”

The GENSPECT parents and others quoted by Bazelon suggest that exposure to transgender kids, education about trans people, and trans ideas on the internet could spread transness to others who might otherwise never have questioned their gender.

“Some Genspect parents told me the rise in trans-identified teenagers was the result of a ‘gender cult’ — a mass craze,” Bazelon wrote credulously. Other sources quoted suggest their children are simply mentally ill and therefore susceptible to the idea that they might be trans or gender nonconforming.

But if you look at the only excerpt in Bazelon’s piece where Genspect is mentioned, it becomes clear that 1) the language Loewinger borrows almost verbatim from O’Connell, “quotes/quoted extensively,” is a major exaggeration, and 2) O’Connell is failing to pick up on the intended meaning of Bazelon’s reporting.

Here’s the only point in Bazelon’s article where Genspect is mentioned:

To parents who doubt the authenticity of a child’s assertion or oppose medical treatments their kids strongly want, the smooth road to gender care looks like a dangerously slippery slope. Such parents have increasingly found each other online, in Facebook groups and on websites. Last fall, an international group called Genspect started holding web-based seminars that are critical of social and medical transition and, a spokeswoman said, gained thousands of members.

Some Genspect parents told me the rise in trans-identified teenagers was the result of a “gender cult” — a mass craze. (In February, an anonymous parent on a Substack newsletter affiliated with Genspect wrote a post called “It’s Strategy People!” about how the group gets its perspective into the media by making sure not to talk about their kids as “mentally ill” or “deluded.”) Other parents said they were not conservative and generally supported L.G.B.T. rights but not medical transition for their own children or usually for anyone under the age of 18. Several parents argued that though 18 is the legal age to vote, buy a gun and consent to medical treatment, in this single area of medicine — gender-related treatment — the age of consent should be 25, when brain development is largely complete. (At 18, these parents are aware, teenagers can go to Planned Parenthood, one of the largest providers of gender-affirming hormones in the country, and receive hormones after a roughly half-hour consultation and giving consent.)

Several Genspect parents told me their teenagers came out as trans after struggling for years with serious mental-health issues. One mother in Northern California said her child had previously been hospitalized for a suicide attempt and started identifying as trans while spending many hours online. The mother said yes to puberty suppressants at the recommendation of a local gender clinic, but her child became more volatile, she said. Around 15, her child wanted to progress to hormone treatment, which the gender clinic supported, according to emails I reviewed. When the mother refused, she became the object of her child’s fury. “What if I’m wrong?” she asked. “Knowing my kid sees me as the barrier to happiness — that’s the worst part. I feel like a monster.”

So first of all, that’s 365 words in an 11,500-word piece, and a segment with few direct quotes. No one from Genspect is being “quoted extensively,” full stop — On the Media is spreading misinformation about Bazelon’s article. Plus, even that short excerpt is mixed; it really seems to me like Bazelon is trying to show that while some of the parents associated with this group might have legitimate concerns, others have been led to a fairly radical place. Why else would she make a point of highlighting their belief that this medical treatment, and this medical treatment alone, should have an age of consent of 25? Contra O’Connell, there is no sign that Bazelon is treating these views credulously. Rather, she’s being a journalist, as distasteful as that is to some.

Moving on:

Micah Loewinger: I want to ask another question about the sourcing. The trans writer, Masha Gessen, who writes about Russia and LGBTQ issues for The New Yorker, said they really liked the piece, but they told David Remnick in an episode of The New Yorker Radio Hour that they were frustrated by Emily Bazelon’s decision to quote conservative writer Andrew Sullivan.

Masha Gessen: In Emily Bazelon’s excellent piece in The New York Times Magazine last summer about the battle over transgender treatment, there’s a quote from Andrew Sullivan, the conservative gay journalist, who says, “Well, maybe these people would’ve been gay if they hadn’t [socially transitioned],” implying they’re really gay. They’re not really transgender. That really clearly veers into the territory of saying these people don’t exist. They’re not who they say they are.

I like Masha Gessen, but Sullivan is paraphrased in the article, not quoted directly. This is slightly nitpicky, but “quote” means a very specific thing in journalism, and it doesn’t apply here, which shows, again, that OTM did zero independent fact-checking of any of Bazelon’s or the Times’ critics (well, “mild critic” in the case of Gessen).

Anyway, here’s the only place in the piece where Sullivan is mentioned:

There is a separate chapter in the SOC8 that focuses on young children and that recommends that health care professionals and parents support social transition when it originates with the child while also recognizing that for some kids, gender is fluid. An outstanding question, asked by gay commentators like the author Andrew Sullivan, is whether some kids who socially transition today, and remain trans, would have grown up to be gay or lesbian in previous generations. “I know there are worries that effeminate males can be assumed to be female or masculine girls can be assumed to be male,” says Amy Tishelman, the lead author of the SOC8 chapter on children and a child psychologist who is the former director of clinical research at the gender clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital. “That’s not what we’re advocating. Support for trans people should not be a way of limiting what a girl or a boy or a woman or a man or a person can be.”

Sullivan isn’t saying anyone involved “doesn’t exist” — he’s saying in some cases, young people can mix up gender roles and preferences with more durable forms of identity mismatch. This is not a new argument, nor a radical one, and it’s supported by the fact that in clinical samples of gender dysphoric kids evaluated over time before social transition became common, a significant number of them end up being gay and cisgender, while a smaller number ended up being straight and cisgender. (This claim is hotly contested by activists, but they are incorrect. It is complicated to explain but I have done so here for the curious.)

More:

Micah Loewinger: I want to ask you about another criticism that was articulated in the open letter to The Times. In a portion of your article discussing why people might pause or stop gender-affirming care, there’s a paragraph featuring the experience of a person named Grace Lidinsky-Smith, who is described in the piece as someone who “has written about her regret over taking testosterone and having her breasts removed in her early 20s.” She’s been cited in a lot of partisan right-wing coverage.

Grace Lidinsky-Smith: Well, I learned my lesson, but my breasts are never coming back. It’s a [sic] worst mistake that I’ve ever made in my life.

Micah Loewinger: She’s also interviewed in a fairly controversial 60 Minutes piece that came out before your magazine story. The writers of the open letter wrote, “Grace Lidinsky-Smith was identified as an individual person speaking about a personal choice to detransition, rather than the President of GCCAN, an activist organization that pushes junk science and partners with explicitly anti-trans hate groups.”

Okay, good. Finally, On the Media is going to do some reporting On the Media. This has to be where Loewinger says that he and his producers tried to figure out which anti-trans hate groups GCCAN partnered with and provide us with some information, one way or another?

Just kidding! Again, OTM simply passes along the open letter’s claims as true. And in this case, the claim about Lidinsky-Smith is, again, pretty serious. I emailed Loewinger to ask about this but didn’t hear back. Lidinsky-Smith said she never heard from OTM. It should go without saying that if you’re going to accuse someone of partnering with a hate group, as On the Media did here, you should reach out to them for comment. It’s true hackery to fail to do so.

I’m going to skip some other minor but still annoying issues to get to the second part of this segment, in which Loewinger interviews Julie Hollar, “senior analyst and managing editor at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), a left-leaning media watchdog.” OTM didn’t have time to get on the phone with any actual experts in youth gender medicine, but did have time to interview, at length, not one but two individuals who agree with every word of the open letter and who have no criticisms of it.

The worst and most potentially dangerous misinformation in this episode comes when Loewinger asks Hollar to respond to a quote from a recent interview David Remnick conducted with Times publisher A. G. Sulzberger for the New Yorker Radio Hour. In it, Sulzberger defended the importance of covering the “very real debates happening in the medical community.” “There’s an active debate there,” Sulzberger insisted to Remnick. “Our critics have effectively asked us to pretend that debate is not happening for fear that the information could be misused.”

Hollar responds by either lying to the OTM audience intentionally or being too unfamiliar with this issue to provide an accurate response:

Julie Hollar: He’s misrepresenting, I think, the medical consensus. All of the respected major medical organizations in this country have reached a consensus, and that is that gender-affirming care is important. It is lifesaving. There are debates around the margins. Those are not the important story right now. The important story is that all of this kind of care is being taken away from people, no access whatsoever. The right is trying to legislate gender-affirming care out of existence, not just for youth either.

The New York Times has decided that the more important question is, are they going to have issues with bone density that they’ll have to work to correct? I’m getting angry.

It is absolutely, 1,000%, no-debate false to claim that the only debates about youth gender medicine are “around the margins.” It’s bullshit. Borrowing again from The Atlantic, “in Finland, Sweden, France, Norway, and the U.K., scientists and public-health officials are warning that, for some young people, these interventions may do more harm than good.” Every one of these countries is investigating not the margins of this issue, but the fundamental issue of whether youth gender medicine’s benefits outweigh its risks. These countries have all determined that the only honest answer is “we don’t know,” and they have sought to scale back access to these treatments, to varying degrees, as a result (though I think the French are the least far along in doing so).

Hollar works for an organization that relentlessly attacks just about any journalist with a platform who points this out. Then, after doing everything she can to poison the well and to nip any open discussion of this controversy among American journalists in the bud, she has the gall to claim that there’s no controversy here! It’s like if I started hurling rocks at every kid who used a playground, driving them away, and then publicly argued that since no one’s using the playground anyway, we should bulldoze it and build a Target.

This journalism sucks. What On the Media is doing here sucks. It’s grossly irresponsible. It takes genuine effort to produce journalism this bad. It involves jamming your head several feet into the sand, ignoring a large number of newsworthy developments all over Europe — not to mention the growing uncertainty expressed by many American and Canadian clinicians and public health experts — and adopting the hubristic stance that you know a lot more than all these experts, even though you haven’t bothered to interview any of them. Again: it’s intentional. On the Media appears to have chosen not to interview a single expert who disagrees with the sunny view on youth gender medicine they are so carelessly amplifying. Instead, Julie Hollar is treated as an authoritative voice.

She’s angry she even has to address the bone density issue! Do you think she is more or less angry than the Swedish teenager facing severe spinal damage because of what puberty blockers did to their skeleton, or that kid’s parents?

If you tell me that that story is anecdotal, then congratulations, you’ve gotten the point: all we have is anecdotes. We have no good data on whether these treatments work. It’s awful that On the Media is spreading misinformation on such a vital subject, and I mean it when I say that it’s dangerous for them to do so. There are, unfortunately, parents who take their cues on medical controversies from On the Media or Jon Stewart or John Oliver or Science Vs. In 2020, maybe you could excuse some of this — the science is complicated, there are a lot of bad studies muddying the discourse, and the red flags hadn’t started going up all over Europe.

In 2023, though? You’re really just lying to your listeners at this point. But hey, it’s not like this issue is about anything important — just vulnerable kids who often have serious mental health problems — so what’s the worst that could happen? I guess we’ll find out.

Questions? Comments? Godawful media criticism? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Image of the Times building via Getty.

With the exception of this footnote, I’m going to ignore the open letter’s reference to Tom Scocca’s weird claim that the Times has recently published too much about this subject on its front page. If you read Wemple’s article, you’ll see that Scocca can make that claim only by completely ignoring the denominator question; as it turns out, only a very small fraction of the Times’ coverage of transgender issues is remotely controversial to progressives. All I’d add to that is that the focus on the paper’s physical front page is very silly, and smacks of cherry-picking, given that we live in an era in which perhaps 9% of the paper’s readership, at most, routinely consumes its print rather than digital product.

Trans activists have become so dishonest and hyperbolic that they're becoming their own worst enemies. I also don't think they realize how much they are turning off otherwise left-leaning voters. A politician's support for child transition treatment is a deal-breaker for many at the voting booth.

“While the segment does include an interview with Times Magazine editor-in-chief Jake Silverstein, his voice is mostly used to represent the “other side” in the classically superficial style of subpar journalism everywhere — the producers make no independent effort to really get at the truth, and they clearly default to the stance that the open letter authors’ claims are true as written, with just about every editorial choice, big and small, pointing in that direction.”

I apologize for the long quote, but Jake Silverstein’s name is something of a trigger for me.

Silverstein was the NYT magazine editor when Nikole Hannah-Jones published her ‘1619 Project’ essay claiming, among other things, that England was deeply conflicted about slavery at the time of the American revolution. This is incontrovertibly false.

(The only people speaking out against slavery at the time in England, then the most powerful nation on earth, were Quakers and it would be decades before they were allowed in either Parliament or England’s elite universities. They were literally a marginalized minority. The Quakers wouldn’t even began to form the basics of the abolitionist movement until the 1780s. A host of things would have to happen, including the emergence of William Wilberforce and a mass evangelical movement amongst prominent, affluent non-Quaker women in the 19th century, before there was even a hope of making slavery an issue in England. Decades later.)

Silverstein was told by the historian they’d hired to fact-check that these claims weren’t true. He overruled her.

Post-publication he was told by respectful and sympathetic historians in an open letter that they weren’t true. He and Hannah-Jones snidely questioned their motives.

Jake Sillverstein is a sad reflection on the NYT. He has played a real part in fostering the culture of dishonesty and misguided activism in media that this letter (and the subsequent coverage of it) exemplifies.