Not long after Donald Trump was reelected, a Princeton University professor of African American studies went viral for all the wrong reasons. Appearing on MSNBC’s The 11th Hour, Eddie S. Glaude Jr. argued that Trump won because — and you probably know what’s coming — too many voters are racist. “There’s this sense that whiteness is under threat, the demographic shifts, the country isn’t what — all these racially ambiguous children on Cheerios commercials are confusing the hell out of me.”

I didn’t initially know what Glaude was talking about. I’d forgotten that back in 2013, there was in fact a “controversy” involving a Cheerios commercial with a multiracial family. But “controversy” deserves those scare quotes because if you read contemporaneous coverage, you’ll see that on YouTube, the positive ratings outnumbered the negative ones by a very healthy margin. The “story” was that a small group of racist online trolls — or teenagers cosplaying as racist online trolls — were mad. There was no actual meaningful wave of backlash to the commercial, because then, as now, there was almost no market among Americans for outrage over multiracial families.

Glaude is just one pundit, but he’s painting a familiar picture. I hear this a lot from my fellow liberals, and it has been a common postelection cope: Liberals1 are simply trying to make the world better, which includes making it more diverse. These simple, noble, obviously good acts send the right into conniptions, sparking all sorts of unseemly backlash, including the ultimate form of backlash: electing Donald Trump not once but twice.

This is a ridiculous understanding of circa 2024 American politics and power, and it should be retired as soon as possible. It completely absolves liberals of actually standing for anything (other than platitudes), let alone fixing the increasingly dysfunctional organizations we run — organizations that make it all too easy for conservatives to point, laugh, and say “This is who you want running the U.S. government?”

To be sure, the fact that something generates backlash does not mean it’s a bad idea, of course, and American history is rife with examples of violent backlash to ideas that now constitute moral common sense. But overall, the idea that liberals are just trying to improve the world and this enrages the caveman brains of conservatives, leading to backlash and Trump-y outcomes — is a poor model for understanding the present moment. In fact, a great deal of conservative backlash comes not in response to the sorts of things only a reactionary or a racist could be offended by, like a multiracial family, but to genuine dysfunction, political overreach, and, perhaps most important of all, scared silence within liberal-dominated institutions.

Conservatives would obviously attack liberals (and vice versa) even if none of this had happened. That’s the nature of two political tribes locked into what feels like endless combat. So it’s not like if liberals exercised power more responsibly, a thousand flowers would bloom and Republicans would suddenly be less in favor of upwardly redistributive tax cuts.

But at a moment when liberals have less political power than we’ve had in a long time — a situation that will maintain, at the federal level, for at least the next two years — it’s vital we take an honest, self-critical look at how we’ve wielded the power we have had in recent years. Instead, many people are embracing a nonsensical — if comforting — worldview in which the only actors with agency are conservatives, and in which we liberals have no power to choose how to run our institutions, to make tough but strategic decisions, to weigh trade-offs, and so on.

None of this is actually the case.

***

“How have we liberals used our power in recent years?” is obviously a big and complex question, and it goes without saying that I’m going to be able to give a partial answer. So a few examples will have to suffice.

The university system is an obvious place to start, because universities tend to be overwhelmingly dominated by liberals. And here, it’s beyond obvious that liberals have instituted — or allowed to be instituted — unpopular policies that violate most Americans’ notions of fairness.

Writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, Michael Clune, an English professor at Case Western Reserve University, rails (thoughtfully) against the politicization of higher ed. “We Asked for It,” argues the headline, and Clune makes the case that if the Donald Trump 2.0 administration is as harsh on higher education as it is bragging it will be, that’ll largely be the fault of these institutions themselves.

Over the past 10 years, I have watched in horror as academe set itself up for the existential crisis that has now arrived. Starting around 2014, many disciplines — including my own, English — changed their mission. Professors began to see the traditional values and methods of their fields — such as the careful weighing of evidence and the commitment to shared standards of reasoned argument — as complicit in histories of oppression. As a result, many professors and fields began to reframe their work as a kind of political activism.

In reading articles and book manuscripts for peer review, or in reviewing files when conducting faculty job searches, I found that nearly every scholar now justifies their work in political terms. This interpretation of a novel or poem, that historical intervention, is valuable because it will contribute to the achievement of progressive political goals. Nor was this change limited to the humanities. Venerable scientific journals — such as Nature — now explicitly endorse political candidates; computer-science and math departments present their work as advancing social justice. Claims in academic arguments are routinely judged in terms of their likely political effects.

The costs of explicitly tying the academic enterprise to partisan politics in a democracy were eminently foreseeable and are now coming into sharp focus. Public opinion of higher education is at an all-time low. The incoming Trump administration plans to use the accreditation process to end the politicization of higher education — and to tax and fine institutions up to “100 percent” of their endowment. I believe these threats are serious because of a simple political calculation of my own: If Trump announced that he was taxing wealthy endowments down to zero, the majority of Americans would stand up and cheer.

As always, I’d caution anyone from drawing a straight line between public opinion shifts and this or that policy, but overall, Clune’s argument is obviously true. He also points out how this shift in the mission of higher-ed institutions has led to large, unaccountable bureaucracies reaching their tentacles into the daily life of the university. I know that sounds conspiratorial, but it’s true!

[R]ecent years have seen a proliferation of high-level administrators given the task of instituting what amounts to a “shadow curriculum” of student and faculty training, the content of which is the explicit transmission and enforcement of controversial political views about race, gender, sexuality, and power. Even more unsettling has been the cloud of unknowing that has descended over the political imperatives governing faculty and administrative hiring practices.

But we can peek through the fog at some of the specifics. John Sailer, who does good work as the director of higher education policy at the Manhattan Institute, tweeted recently about how “The University of Michigan has hired over 50 professors via initiatives led by its chief diversity officer, Tabbye Chavous.” In his full article, he explains that Chavous ran a project to hire biomedical science faculty from diverse backgrounds which was “partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, along with $63.7 million from the university.” Chavous and her colleagues were able to do an end-run around restrictions on hiring on the basis of race by making diversity statements a mandatory part of the hiring process — this, they believe on the basis of a past program, can be a very useful proxy for race.

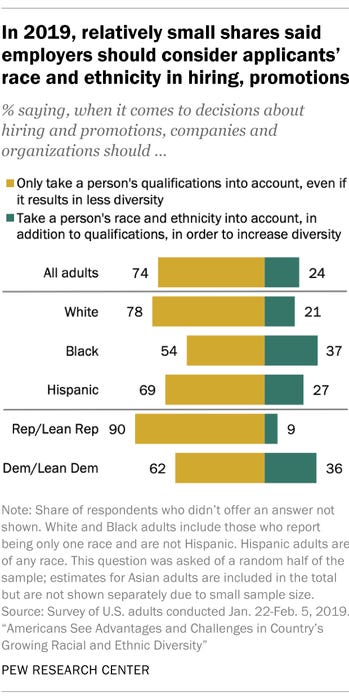

Let’s pause for a minute. Chavous has a PhD in community psychology. Should a diversity administrator with a PhD in community psychology be running an initiative to hire dozens of new biomedical science faculty? If so, why? Is this a good use of public funds? Does it advance the long-term interests of the University of Michigan? Since there are obvious trade-offs to any situation in which you decide to devote finite resources to hiring in one area, and in which you change the criteria for hiring, are these trade-offs worth it? What about the fact that, even setting aside legal issues, racial preferences in hiring are overwhelmingly unpopular among Americans, including a majority of black ones?

Should the University of Michigan have set up a bureaucratic entity to ensure the decisions to hire biomedical researchers are tilted more toward diversity concerns than academic merit as it is normally defined?

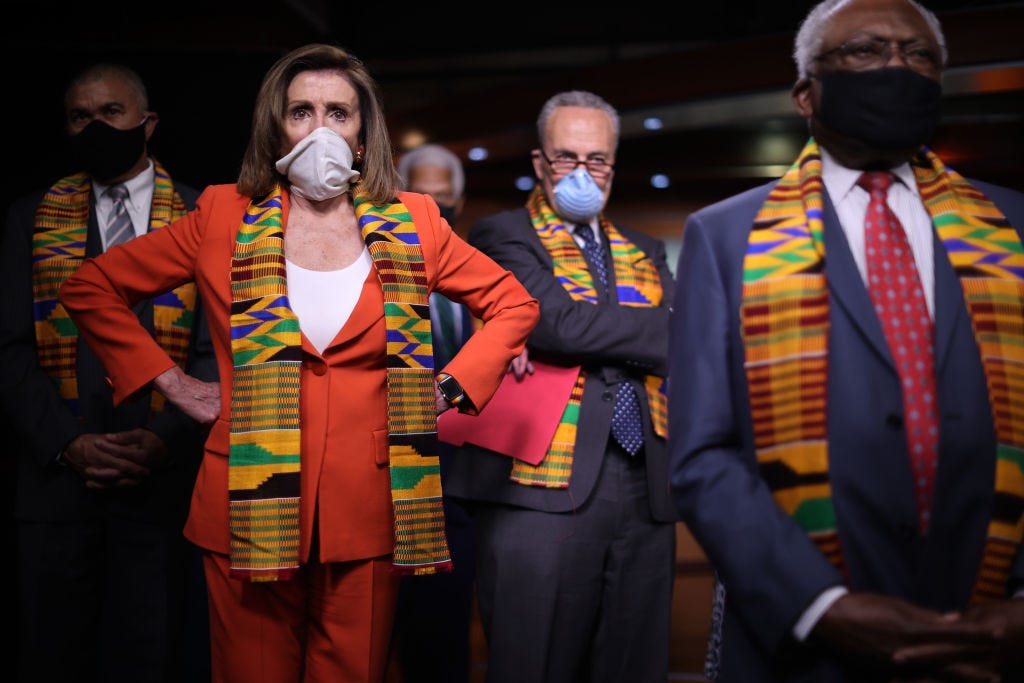

There was no real conversation about this. It all just sort of. . . happened. Of course, that can also be said of many of the revelations in Nicholas Confessore’s New York Times Magazine article on UM’s failed $250 million DEI gamble, including a training where the entire law faculty was urged by an outside “facilitator” “to require students to declare their preferred pronouns and furnished [them with] a list of dozens of sexual orientations.”

Who asked for any of this? Who thought it was a good idea?

***

Let’s jump from the Midwest to the West Coast, and from higher ed to secondary ed. On a recent episode of my podcast, Katie Herzog mentioned an article in the Los Angeles Times from October of last year headlined “How conservatives are waging a coordinated, anti-LGBTQ+ culture war in California schools,” written by Kevin Rector, Howard Blume, and Mackenzie Mays.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Singal-Minded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.