Twitter Has Almost Nothing To Do With “Marginalized People”

On an exceptionally silly argument

I unlocked this post on 8/18/2022. I was only able to write it because of my paying subscribers, so if you find this sort of work useful, please consider becoming one:

Indulge me in a rant about a very, very annoying argument.

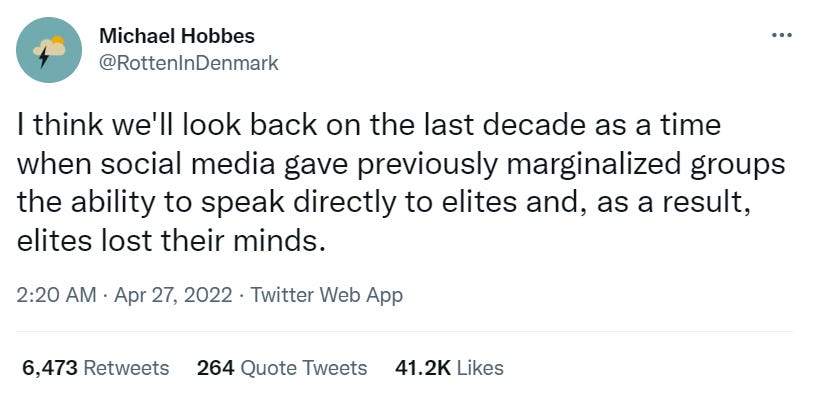

It’s this one: “I think we'll look back on the last decade as a time when social media gave previously marginalized groups the ability to speak directly to elites and, as a result, elites lost their minds.”

I do not like Hobbes, but he’s expressing an extremely common view about what Twitter is: some sort of great equalizer or pro-democratic force. Anyone who expresses skepticism about Twitter, particularly the view that the stuff going on there under the guise of social justice often isn’t really about social justice, will at some point get a version of this response: You’re just mad that marginalized people now have a greater voice and can directly challenge power.

It’s a cute trick. If Twitter is The Voice of the People, then anyone who argues that elites shouldn’t view Twitter nonsense as important, or who suggests that the platform promotes unfriendly deranged psychotic social norms and the broken individuals who most exemplify them, can be tarred as an enemy of The People. And who wants to be that? The People are great!

This is a ridiculous argument, though, at least in my corners of Twitter (media and academic). Twitter is, above all, a tool for privileged people to defend and promote their own values and priorities to other privileged people.

Let’s First Steelman This

I don’t want to forge ahead without acknowledging the kernel of truth here. In certain, fairly circumscribed senses, Twitter can be used to bridge power differentials. Twitter is one of the most frictionless machines ever devised (or forged in hell itself) for the spread of information, so for any problem caused by the suppression of information, Twitter can, in theory, be beneficial.

Academic transparency is a useful example that I have some familiarity with. Here’s an excerpt from a 2016 piece I wrote about the time Susan Fiske, a legendary social psychologist, referred to the “methodological terrorism” she was seeing online — by which she mostly meant social scientists harshly criticizing the quality of other social scientists’ work:

The researchers who have the most at stake here are debunkers — those who have discovered errors, fraudulent or otherwise, in other people’s work, and have attempted to get them fixed. Generally, this is not an easy thing to do; social science, and science in general, frequently swat angrily at attempts at correction. But what’s striking is that when debunkers tell stories about how frustrating and bruising it was to get even straightforward errors fixed, they blame exactly the norms Fiske seems intent on defending, such as the presumption that published findings need to lent a certain gravitas and critiqued only in a very specific, sanctioned manner, and the idea that it’s untoward to bring too much attention to other researchers’ possible errors.

The political scientist David Broockman, for example, was delayed in his discovery and publication of Michael LaCour’s fraud by prevailing social norms which caused friends and colleagues to tell him to stay quiet, to keep potentially explosive early hints that something was amiss to himself, lest it harm his career since he’d be seen as attacking a senior researcher (Don Green, the now-retracted paper’s co-author) and a blockbuster finding. He even pasted some of his statistical findings to PoliSciRumors.com, an anonymous academic message board consisting largely of the sort of vitriol Fiske decries in her column, hoping someone else would pick up and run with the weirdness he’d uncovered, since he was so frightened to do so.

Then there’s Steven Ludeke. While a graduate student at the University of Minnesota, he noticed a couple of very simple published errors involving the psychological construct of “psychoticism,” and in a careful, by-the-book fashion, had his adviser reach out to one of the authors who had erred. This led to a years-long ordeal, the details of which you can read here, in which those authors gave him the runaround, refused to share their data, and tried to slag Ludeke — to others in the field and, once I began reporting on the story, to me — as an obsessed zealot, when the extensive email record Ludeke shared with me showed he’d been polite throughout his attempts to alert the authors to their error and gain access to their data.

In light of all of this, Ludeke doesn’t have much faith in the ability of the traditional approach to getting errors rectified. “The amount of time that this project took for me, the amount of time and the amount of stress, makes this clearly a bad choice to have pursued, unequivocally,” he said back when we first spoke over the summer. “If you have a chance to say something to that effect in the article — ‘I do not find this to be a recommendable experience’ — I would like that.” And when I emailed him to ask about Fiske’s column, he told me that, while “[t]here are points worth discussing” on the civility front, “The idea that the playing field is somehow currently balanced against the authors of a given piece in favor of those critiquing a particular piece is entirely inconsistent with my own experience.” He’s also worried about the potential effects of big-name researchers like Fiske criticizing the recent trend toward online openness. “It might be that the defensive responses from senior people have convinced some [young researchers] that there’s no need to update their approach to research,” he said, despite the steady stream of errors highlighted by Gelman and others which hint strongly that social-science researchers must get more methodologically rigorous. “That would be sad, if true.”

Twitter can, in theory, help get the word out about questionable social science. There’s certainly less gatekeeping there. Anyone who finds something suspicious can post it, alert others, and hope that word spreads within a given scientific community.

Even here, though, I hesitate to say that Twitter is of greater net benefit to less powerful people than more powerful ones. For every righteous instance of a young academic raising alarms about shoddy research by a big-name professor on Twitter, it seems there are three or four examples of that aforementioned frictionlessness being used to attack less powerful academics — often for questionable reasons.

Have you seen how academics treat one another on Twitter? From where I sit, there’s much more of that sort of ganging up going on than anything that can accurately be described as the powerless speaking truth to power.

Who Gets To Be In The Room?

I think when Hobbes or the many others who make this argument do so, they’re referencing the fact that Twitter appears to be quite diverse. There are a lot of boring, rapidly aging white media types like me, but there are also other Twitters, often centered on groups that have been historically marginalized. The most famous of them is called Black Twitter, but of course there are many others, including Trans Twitter and Disability Twitter and Sex Worker Twitter and so on.

This is good! I’d much rather Twitter have a lot of different groups from different backgrounds than it be an Upper East Side cocktail party.

But is it as far off from an Upper East Side cocktail party as people seem to think?

One of the better essays written in the last couple years is “Being-in-the-Room Privilege: Elite Capture and Epistemic Deference” by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, a philosopher at Georgetown University. Táíwò’s piece is about “the popular, deferential applications of standpoint epistemology” found in elite spaces:

Broadly, the norms of putting standpoint epistemology into practice call for practices of deference: giving offerings, passing the mic, believing. These are good ideas in many cases, and the norms that ask us to be ready to do them stem from admirable motivations: a desire to increase the social power of marginalized people identified as sources of knowledge and rightful targets of deferential behaviour. But deferring in this way as a rule or default political orientation can actually work counter to marginalized groups’ interests, especially in elite spaces.

That’s because the subset of people from marginalized groups you’ll find in a newsroom, or a philosophy department, or on an NGO’s board, tend to look very different from other members of that group:

Some rooms have outsize power and influence: the Situation Room, the newsroom, the bargaining table, the conference room. Being in these rooms means being in a position to affect institutions and broader social dynamics by way of deciding what one is to say and do. Access to these rooms is itself a kind of social advantage, and one often gained through some prior social advantage. From a societal standpoint, the “most affected” by the social injustices we associate with politically important identities like gender, class, race, and nationality are disproportionately likely to be incarcerated, underemployed, or part of the 44 percent of the world’s population without internet access – and thus both left out of the rooms of power and largely ignored by the people in the rooms of power. Individuals who make it past the various social selection pressures that filter out those social identities associated with these negative outcomes are most likely to be in the room. That is, they are most likely to be in the room precisely because of ways in which they are systematically different from (and thus potentially unrepresentative of) the very people they are then asked to represent in the room.

Táíwò uses himself as an example of how this dynamic plays out:

My parents’ qualification as skilled labourers does much to explain their entry into the country and the subsequent class advantages and monetary resources (such as wealth) that I was born into. We are not atypical: the Nigerian-American population is one of the country’s most successful immigrant populations (what no one mentions, of course, is that the 112,000 or so Nigerian-Americans with advanced degrees is utterly dwarfed by the 82 million Nigerians who live on less than a dollar a day, or how the former fact intersects with the latter). The selectivity of immigration law helps explain the rates of educational attainment of the Nigerian diasporic community that raised me, which in turn helps explain my entry into the exclusive Advanced Placement and Honours classes in high school, which in turn helps explain my access to higher education...and so on, and so on.

Táíwò is connected by blood to many Nigerians back in Nigeria, but his daily experience of life is completely different from most of theirs. Táíwò is connected by a very superficial racial categorization to many other black Americans, but his daily experience of life is completely different from most of theirs. To reduce him to a member of these identity categories — let alone to treat him as a representative member — would be to engage in an act of wildly dunderheaded essentialism.

The People On Twitter Overlap A Lot With The People Who Get To Be In The Room

What is Black Twitter most concerned with? It’s a big, diffuse group, so of course its members don’t agree on everything. But certain patterns emerge, and there’s a heuristic that will almost always point you in the right direction, whether you’re asking this question about Black Twitter or some other group.

“Twitter Is Not America,” said the headline of a 2019 article in The Atlantic by Alexis C. Madrigal. He reported on something that surely we all already knew:

Twitter, as it turns out, is not a good model of the world.

Hard as that is for the Twitter-addicted to believe, it is true, and a recent Pew Research study presents new evidence about the way that the platform leans.

In the United States, Twitter users are statistically younger, wealthier, and more politically liberal than the general population. They are also substantially better educated, according to Pew: 42 percent of sampled users had a college degree, versus 31 percent for U.S. adults broadly. Forty-one percent reported an income of more than $75,000, too, another large difference from the country as a whole. They were far more likely (60 percent) to be Democrats or lean Democratic than to be Republicans or lean Republican (35 percent).

There’s also a massive divide between casual and power users.

As Madrigal writes:

Pew split up the Twitter users it surveyed into two groups: the top 10 percent most active users and the bottom 90 percent. Among that less-active group, the median user had tweeted twice total and had 19 followers. Most had never tweeted about politics, not even about Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s meeting with Donald Trump.

Then there were the top 10 percent most active users. This group was remarkably different; its members tweeted a median of 138 times a month, and 81 percent used Twitter more than once a day. These Twitter power users were much more likely to be women: 65 percent versus 48 percent for the less-active group. They were also more likely to tweet about politics, though there were not huge attitudinal differences between heavy and light users.

All of this follows pretty naturally from the question of who we’d expect to have both the time and inclination to tweet a lot. To have the time, you either need a relatively leisurely life, a job where you’re already at a computer or on your phone most of the day and can tweet without getting in trouble with your boss, or both. As for inclination… well, it depends. But I’d argue that you’ll be most inclined to tweet a lot if you can find other people like you.

Which points us toward highly educated types in fields like media, academia, and tech. You know who’s much less likely to be tweeting? Poor and working-class people, who are less likely to have the daily flexibility to do so, and who will not find a welcoming or familiar atmosphere, at least not on most of Twitter, if they do poke their head in.

So there’s your heuristic. What does Black Twitter care about? On average, it will care about issues that are relevant to higher-income, more highly educated and liberal members of that group. On average, Trans Twitter will care about the issues that are relevant to higher-income, more highly educated and liberal trans people, and Disability Twitter will care about the issues that are relevant to higher-income, more highly educated and liberal disabled people, and right on down the line. You can even apply this to my Twitter, Media Twitter. Media Twitter is dominated by the views most relevant to higher-income, more highly educated and liberal media types.

Black Twitter is probably the most important example, though, and it really highlights the problem with understanding Twitter as a megaphone for “marginalized” people. “For people who aren’t on the inside, [Black Twitter is] sort of an inside look at a slice of the black American modes of thought,” Jonathan Pitts-Wiley told Farhad Manjoo in 2010. “I want to be particular about that—it’s just a slice of it. Unfortunately, it may be a slice that confirms what many people already think they know about black culture."

What a lot of white people “already think they know about black culture,” in my experience, is that black radicalism is a dominant mode of thought within that community. Black people are eager to tear down existing structures of injustice — they’re tired of waiting politely for things to change and very frustrated by how racism continues to destroy their communities. This seems to be reflected among the most popular voices of Black Twitter. If you go to the Essence article telling you which Black Twitter voices to follow, plug each name into Google or the Twitter search bar, and search for “abolition,” you’ll see that the top three are all in favor of police abolition (it’s slightly complicated with the second link, Deray McKesson, and he’s tried to thread the needle a bit, but in that Medium essay he clearly writes the eventual goal is abolition).

Black Twitter doesn’t speak with one voice on this subject, of course — other individuals on the list have different views. But no one can deny that if you are a progressive, and you follow the people you’re supposed to follow on (political) Black Twitter, on average you’ll see a lot of talk about police abolition, the idea that racism is a ubiquitous force in American life, and so on.

But most black Americans don’t want to abolish the police. They don’t even want to partially defund the police! “Only 18% of respondents supported the movement known as ‘defund the police,’ and 58% said they opposed it,” noted USA Today last year, reporting on a TODAY/Ipsos Poll. “Though white Americans (67%) and Republicans (84%) were much more likely to oppose the movement, only 28% of Black Americans and 34% of Democrats were in favor of it.”

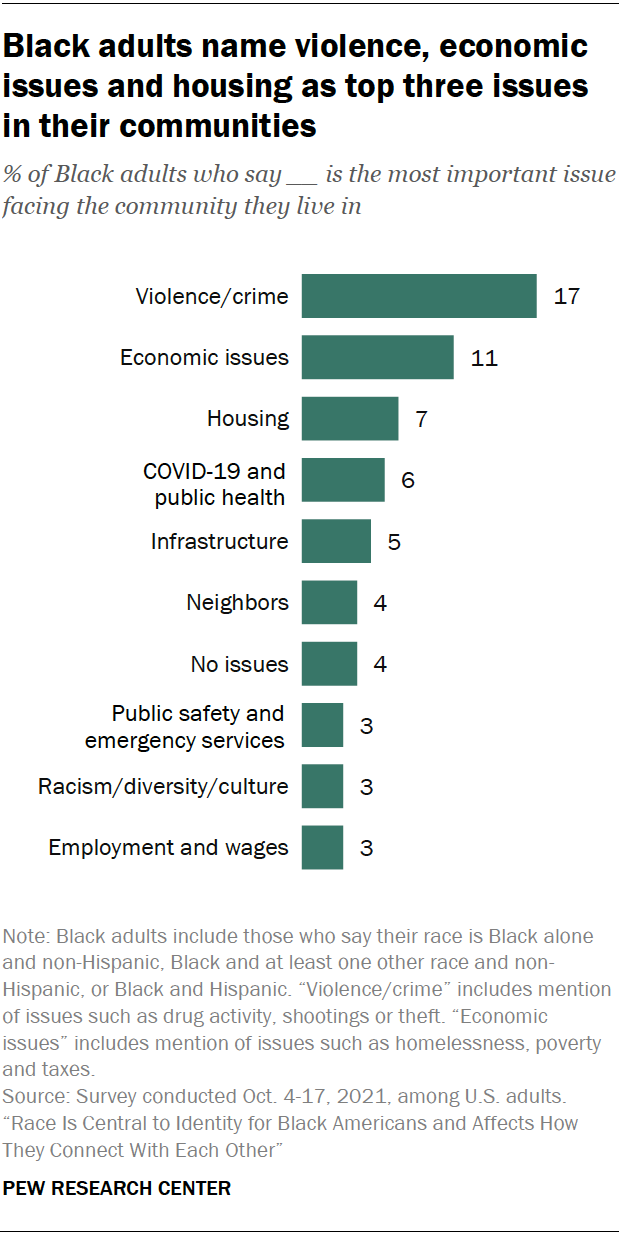

Nor does the focus on abolishing broken systems reflect the concerns of the average black American more broadly:

If we believe this poll, about six times as many black Americans view violence and crime — as opposed to racism — as the most important issue facing their community. It isn’t close. “Economic issues” and “Housing” aren’t far behind. While there’s a lot of talk of injustice and inequality on Black Twitter and in other progressive Twitter subcultures, you’ll find that meat-and-potatoes talk of these subjects tends to be beaten out by more radical talk of destroying (what is seen as) a fundamentally broken system. (This should go without saying, but majority views aren’t necessarily correct — my point is not that the average X person is more ‘correct’ about various issues than the average X person who is a Twitter power user, but rather that they are simply likely to have different views.)

Education explains much of this divide. There are massive differences between how more educated and less educated people talk, think, and prioritize, and college-educated people of any race are much more likely to focus on issues like white supremacy and police violence than non-college-educated individuals. The view that America is fundamentally broken and white supremacist is, ironically, a view that is more likely to be held by a highly educated, well-off individual than by a poor one (all else being equal).

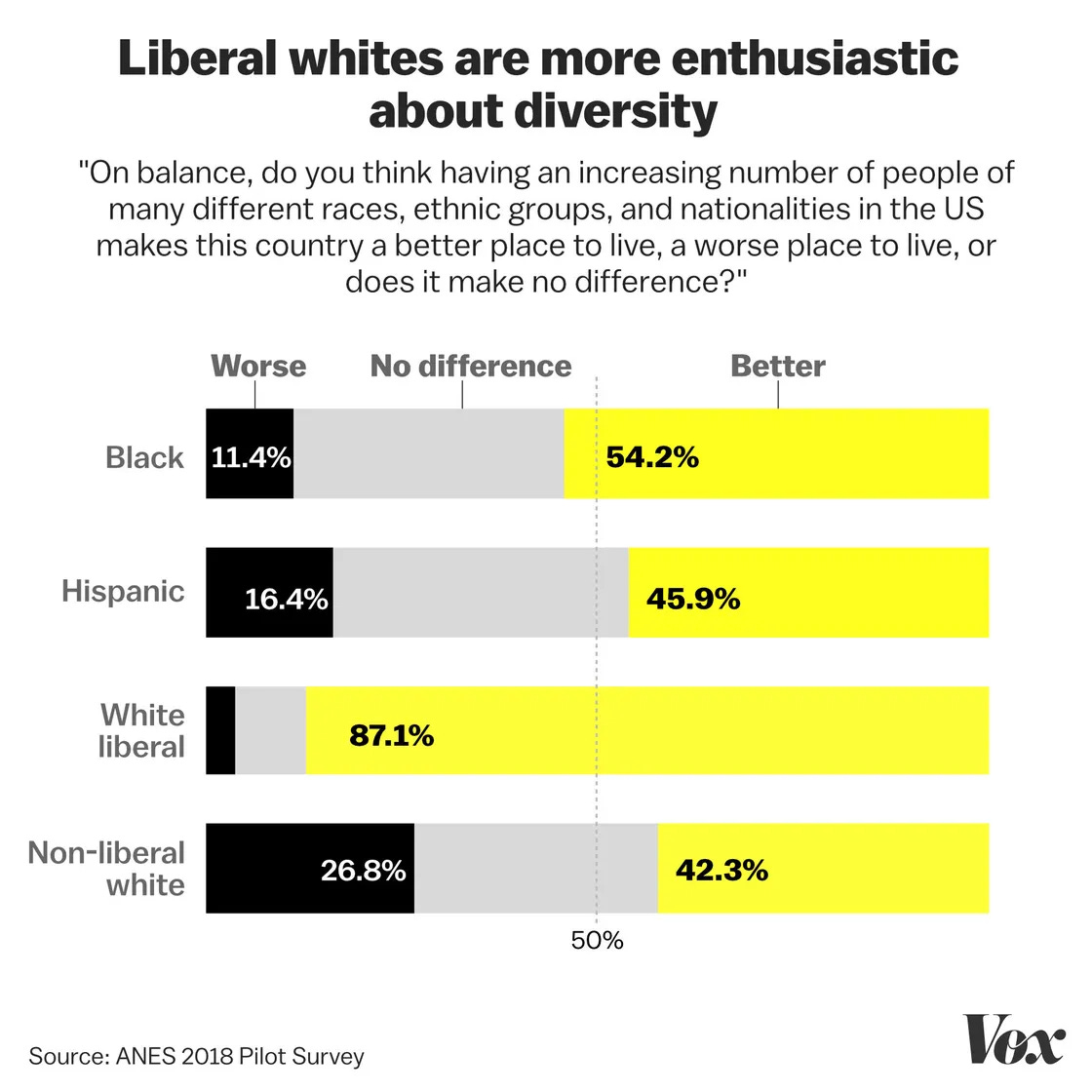

I can only link to Matt Yglesias’ “Great Awokening” article so many times, but it remains important. Controlling for everything else, education seems to be associated with further left views. When it comes to the big racial groups (black, white, Latino), and controlling for left-of-center political orientation, whites are the most educated, by far, and also have the leftiest political views, by far.

This is true not only on radical questions like whether we should abolish the police, but even on much more basic ones like whether it’s better to have more diversity in the U.S.:

Black people are overwhelmingly Democratic, but they’re torn on this question. White liberals claim to love diversity. They also have much more leftward views on the question of whether black people should, like other groups (according to this question), work their way up “without special favors”:

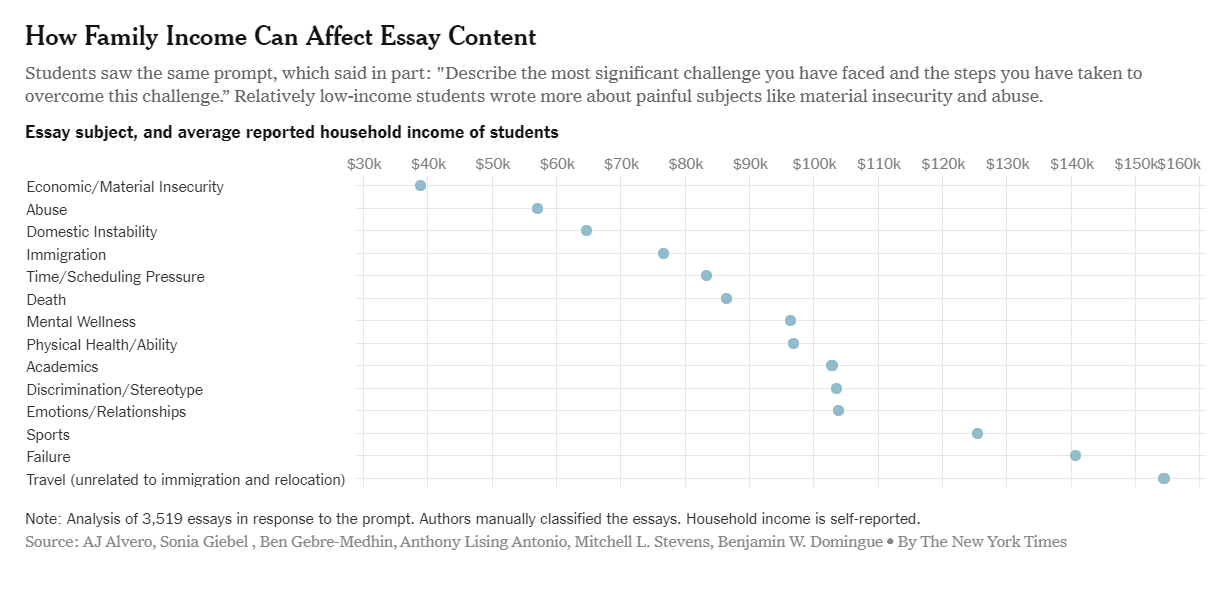

These differences pop up everywhere once you know to look for them. My “favorite” example comes from this study, which I previously mentioned here, which examined the content of California college admissions essays:

Kids who described their most significant challenge as being related to what the researchers classified as “Economic/Material Insecurity” came from households that made less than $40,000 a year. Kids who described their most significant challenge as being related to “Discrimination/Stereotype” came from families that made more than $100,000.

People with more money and/or education are socialized to see the world, and politics, differently from poorer people. This is not a novel observation, but people forget how it applies to Twitter. And I don’t think it’s an accident that the skew between the online community we call “Black Twitter” and the broader population of black Americans points in the direction of positions white liberals are sympathetic to: police abolition, an intense focus on race and white supremacy, and so on.

Who Is Being Listened To?

I think the same thing happens just about everywhere. Newspapers, NGOs, and universities increasingly look to Twitter — sometimes a bit sweatily — to make sure they are saying and doing the right thing, but Twitter is dominated by leftier, wealthier, more educated people. Many of those people aren’t white, or fit in some other “traditionally marginalized” category, but that doesn’t mean they come anywhere close to being “marginalized” in the sense of struggling to subsist day to day.

So there’s a degree of tokenization taking place. It isn’t powerless people speaking truth to the privileged; it’s privileged people speaking to other privileged people. And I think when media outlets, in particular, start listening to Twitter more because it is supposedly where the “powerless” are, it doesn’t necessarily lead them toward better, more inclusive coverage. I think it can sometimes do the opposite: If you believe, as I do, that the media’s police abolition fad was partially driven by Twitter, then Twitter helped produce some very shoddy, strangely circumscribed coverage of a policy proposal that is deeply unpopular among black Americans. Twitter helped convince newsrooms that police abolition is a “black” cause, because they looked to Twitter to find black people to take their cues from, and on Twitter, privileged people tend to carry the day.

It’s pretty perverse to claim that this is an example of powerless people making their voices heard. It’s also self-serving.

Questions? Comments? Other institutions we should abolish, such as podcasts and newsletters? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The stock illustration of a fancy party (like Twitter) comes via Getty.

It's not even so much that Hobbes and his ilk are far to the left of most people, it's that they're so incredibly MEAN about it. They yell all day, dunk on people all day, paint good-faith disagreements as moral monstrosities, and alienate so, so many would-be converts with their behavior.

The default mode of expression with these people is basically: "Hahaha, I can't believe you're so fucking stupid, imagine thinking anything other than what we believe, and I shouldn't even have to explain it to you."

It's a behavior that makes countless enemies and few friends. It's Mean Girls behavior, and Twitter is their eternal high school, where they never have to leave their hive of Cool People.

This was great, thanks!

It is funny how one of the many psychological tricks social media has played on its users is that it's convinced upscale urban liberals that they are the voice of the people (TM), that they are the literal incarnation of justice and equality, and therefore any disagreement with them is punching down on the helpless oppressed.

I think this is partly the inevitable downstream effect of the New Left defeating the Old Left, when the battle against inequality and oppression moved from union halls and shop floors to the Humanities Depts, so whereas being a member of the Old Left meant attending a strike w smelly workers and their suspiciously retrograde beliefs, being a member of the New Left means you can stay in the library and battle oppression by interrogating texts, policing language and crafting jargon (Symbol manipulators of the world unite!).

Part of this too is that whenever a new ruling class coalesces and begins to solidify its place at the top of the food chain, it wants of course to be seen as financially and intellectually superior, but also as morally superior.

Moral legitimacy is as crucial to a ruling class as the police or the army.