The Police-Abolition Fad Won Progressives Nothing But Backlash And Misunderstanding

An autopsy of a journalistic error driven by privileged people

From time to time I am going to unlock older posts that were originally just for paying subscribers. When I do, I’ll create a free clone of them with comments disabled, so as to protect the privacy of paying subscribers who commented on the original. This is one such clone — it was created 2/1/2021. If you’re a paying subscriber and want to see or comment on the original, it lives here.

The only reason this post exists is because of my paying subscribers, so if you enjoy this or find it useful please consider becoming a paying subscriber:

Police abolition has been super hot since George Floyd was killed back in late May. How hot? In a mid-June review of Alex Vitale’s 2017 book The End Of Policing, one of the bibles of that movement (and available for free here), Matt Yglesias ran down the copious recent coverage the book had received:

When the activist Mariame Kaba wrote her June 12 op-ed “Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police” in the New York Times, her rebuttal to the concern about rising crime was to cite Vitale. And he’s been ubiquitous in left-leaning media since the protests against the killing of George Floyd and broader police violence and systemic racism started. You can read his interview in Jacobin or Mother Jones or the Nation, or listen to him on Democracy Now. He’s also been a prominent voice in more mainstream media, appearing on an Atlantic podcast and NPR’s All Things Considered (and Code Switch) and quoted at least three times in the Washington Post.

I haven’t read The End Of Policing, but Yglesias, who is a very trustworthy voice on policy matters, accuses Vitale of not really bothering to answer the first question anyone will ask when the subject of police-abolition is brought up: What about violent crime?

As Yglesias writes:

[T]here’s a substantial literature in economics and sociology arguing that more police on the beat equals less violent crime. One effort to quantify this precisely is a 2018 Review of Economics and Statistics article by Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary. It estimates, based on a big set of police and crime data from large and midsize cities between 1960 and 2010, that every $1 spent on extra police generates about $1.63 in social benefits, primarily by reducing murders. One needn’t take this literature as gospel truth, but one of the go-to scholars on the abolitionist position should be able to — and want to — counter the prevailing academic claim that investments in policing pay off in reduced violent crime.

While Yglesias has examined the policy nuts and bolts of this debate much more closely than I have, I have gotten the same impression, over and over, whenever I have read about it: Police abolitionists don’t have answers to rather basic questions about their position and its implications.

Take the “Yes, We Mean Literally” column published in the most important newspaper in the world:

What about rape? The current approach hasn’t ended it. In fact most rapists never see the inside of a courtroom. Two-thirds of people who experience sexual violence never report it to anyone. Those who file police reports are often dissatisfied with the response. Additionally, police officers themselves commit sexual assault alarmingly often. A study in 2010 found that sexual misconduct was the second most frequently reported form of police misconduct. In 2015, The Buffalo News found that an officer was caught for sexual misconduct every five days.

None of what follows “What about rape?” explains how society would investigate sexual assaults, and bring their perpetrators to justice, in the absence of police. It doesn’t make sense to say we should stop doing X because X hasn’t solved problem Y completely, of course. Nor does it make sense to say that police should be abolished because they treat rape victims insensitively or commit assaults themselves. These are all reasons to reform the system, not get rid of police.

Maybe in 20 years we’ll be talking more seriously about police abolition. Who knows? But in the meantime, this is a very immature and unsophisticated movement — I know that sounds harsh, but what else should we call a movement that hasn’t bothered to come up with a decent response to the single biggest critique of its raison d’etre? And it’s striking how softball most of the coverage has been. I don’t want this article to become a buffet of media criticism but in the NPR interview with Vitale, for example, his answer to the violence question is “We have community-based anti-violence initiatives that have shown real success in reducing homicides and shootings without relying on mass incarcerations.”

This, again, isn’t really an adequate response, unless Vitale — or someone — can show that these programs are at least as effective as policing at reducing violent crime, explain how they would handle murderers without incarcerating them in a hypothetical no-police scenario, explain what should happen in communities where these initiatives don’t happen to spring up, and answer a bunch of other followup questions. But the host doesn’t ask any.

***

In addition to not being anything close to a fleshed-out policy proposal, police abolition also isn’t popular. Hell, its much milder cousin, police defunding, isn’t popular either.

Here, some of the most telling recent polling comes out of Minneapolis, the site of Floyd’s killing and a great deal of unrest this summer. A Minnesota Public Radio News/StarTribune/KARE-11 Minnesota Poll published in August, during what one would have imagined to be a crest of anti-police sentiment, did find that there was overwhelming support for the general policy of “redirect[ing] some funding from the police department to social services,” by a 73-24 margin.

Some funding. Sure — that’s part of the broader progressive critique, often voiced by police officers themselves, that in our society cops are sometimes dispatched to resolve problems they really shouldn’t be in the business of resolving. There are certainly some situations where a social worker or crisis counselor type might be more appropriate, for example, and God knows terrible outcomes have sometimes resulted from police being dispatched to ‘assist’ people dealing with mental-health crises who don’t pose a threat to anyone but themselves.

But a funny thing happened as soon as the pollsters got a bit more specific. When Minneapolitans were asked whether the size of the police force should be reduced, residents of this extremely liberal city said no by a slight margin, 40-44. The gap was larger for black residents (35-50) than it was for white ones (41-44). And keep in mind that the question is whether the police force should be reduced at all — not whether it should be reduced in the transformative manner called for by many advocates for defunding and abolition. The idea is likely unpopular because people think — accurately, if you believe the above-mentioned Yglesias review or a bunch of other research — that fewer police means more violent crime: “When asked how a significant reduction in the size of the force would impact crime, residents tended to believe it would make them less safe. Overall, 48 percent said it would have a negative impact on public safety while 26 percent said it would be positive. Fourteen percent said it would have no effect and 12 percent weren’t sure.”

This racial gap in enthusiasm for defunding the MPD can perhaps be explained by another racial gap that popped out of the polling: “Black residents were more likely than whites to say crime is on the rise. The poll found that two-thirds of Black residents and fewer than half of whites say crime has gone up.” Funny how easy it is to support police abolition or defunding when you don’t have much personal experience feeling threatened by crime, because you live in a safe neighborhood.

***

Everything in the universe circles back, inevitably, to The New York Times (sigh). In June I wrote a critical piece about a front-page Times article about the police-abolition movement. That story, with three bylines and a small army of contributors, simply ignored all the polling that suggests black Americans are not generally supportive of defunding or abolition. Black voices who are skeptical of these policies were absent from the piece.

More recently, the Times ran a story headlined “How a Pledge to Dismantle the Minneapolis Police Collapsed” by Astead Herndon, one of the contributors on the original piece.

Over three months ago, a majority of the Minneapolis City Council pledged to defund the city’s police department, making a powerful statement that reverberated across the country. It shook up Capitol Hill and the presidential race, shocked residents, delighted activists and changed the trajectory of efforts to overhaul the police during a crucial window of tumult and political opportunity.

Now some council members would like a do-over.

Councilor Andrew Johnson, one of the nine members who supported the pledge in June, said in an interview that he meant the words “in spirit,” not by the letter. Another councilor, Phillipe Cunningham, said that the language in the pledge was “up for interpretation” and that even among council members soon after the promise was made, “it was very clear that most of us had interpreted that language differently.” Lisa Bender, the council president, paused for 16 seconds when asked if the council’s statement had led to uncertainty at a pivotal moment for the city.“I think our pledge created confusion in the community and in our wards,” she said.

Herndon explains that interviews with “about two dozen elected officials, protesters and community leaders described how the City Council members’ pledge to ‘end policing as we know it’ — a mantra to meet the city’s pain — became a case study in how quickly political winds can shift, and what happens when idealistic efforts at structural change meet the legislative process and public opposition.”

It’s striking the way the first story didn’t spend any time grappling with the policy or political obstacles to police abolition or large-scale defunding — and there were reams of prior polling suggesting this was a politically infeasible policy — in favor of platforming enthusiastic proponents of such ideas.

I don’t know if the authors of that original story intentionally left out anti-abolition voices, but I was struck by this quote from Minnesota Public Radio’s coverage of the aforementioned Minneapolis polling:

Jasmine Elliston is Black and lives less than a mile from where George Floyd was killed. Elliston said the presence of officers may make some African Americans nervous, but they don't want police to leave.

“I don't think anybody I know personally is like, ‘I don't want police in my neighborhood.’ I want police in my neighborhood that look at me as a person first, and not a perpetrator.”

Decades worth of polling suggests that, at the risk of overgeneralizing, this is the most common black American view on policing. Poll after poll has shown these Americans believe police should play an important role in keeping their neighborhoods safe, but they often come up short, either by not showing up when they’re needed or by acting in an abusive manner toward the people they are supposed to serve. Not only does Elliston hold the view that she wants police in her neighborhood, but she insists that she doesn’t know anyone who feels otherwise. And yet the Times couldn’t find a single black voice to express this view in its first article. It ended up providing no broader context whatsoever and leading from behind, only catching up to reality with the followup story.

Why is that? To return to a theme I’ve beaten over the head in this newsletter, this really comes down to class and education and a lack of sufficient attention to the views of the sorts of people who don’t subscribe to The New York Times. If you are the type of individual who works for a progressive newsroom or organization, you have lots of people in your immediate social and professional networks who are super enthusiastic about police abolition and defunding. If you’re the average black person living in Minneapolis, on the other hand, you’re part of a community that opposes any reduction to your local police by a healthy 15-point margin.

The politicians discussed in Herndon’s story were arguably tricked, by the first wave of activists who responded to Floyd’s killing, into thinking a true groundswell movement in favor of abolition or defunding had taken root in Minnesota. But while I’m sure there are many activists and organizations who continue to loudly call for these policies, there is no such groundswell. And Minneapolis is one of the most liberal cities in the country — you can imagine how these policies would poll elsewhere.

***

From the progressive point of view, I think this has all been very bad. For those of us who do have deep concerns over the criminal justice system, what has this monthslong fixation on defunding and abolition in mainstream media, complete with softball coverage that doesn’t engage with these policies’ shortcomings at all, won us?

Nothing but backlash and misunderstanding. The Minnesota politicians who flirted with these policies had to backtrack. Conservative media, meanwhile, has been able to gleefully paint progressives or Democrats or both as deeply committed to fundamentally cutting back on, or eliminating altogether, policing in the United States. Is this an unfair exaggeration? Yes. But it wasn’t made up out of thin air! There was, after all, a huge amount of credulous media coverage suggesting these ideas are quite popular in progressive spaces. You wouldn’t be crazy for, upon perusing NPR’s or The New York Times’ coverage, believing these to be mainstream progressive policies.

The nice thing about criminal-justice reform is that it has enjoyed bipartisan support in recent years. Or some elements of it have, at least. There is a visceral unfairness to bad law enforcement, to people rotting in prison over nonviolent drug offenses, to the broken public-defender system, to the image of a baby being critically injured by a flashbang grenades hurled carelessly during a no-knock raid, and all the other awful symptoms of a system that grew frightfully bloated and ravenous and out-of-control over the years — and most normal humans, faced with this unfairness, come to believe it should be remedied.

That’s part of the reason things are improving, at least according to metrics like the incarceration rate, even as there remains work to be done:

Can you imagine a more self-sabotaging way of jeopardizing this progress than to broadcast to millions of Americans that really, the core of the criminal-justice-reform movement is about drastically cutting back on police, or getting rid of them altogether? When these policies don’t even appear to enjoy significant support, once you dig into specific questions, among liberals?

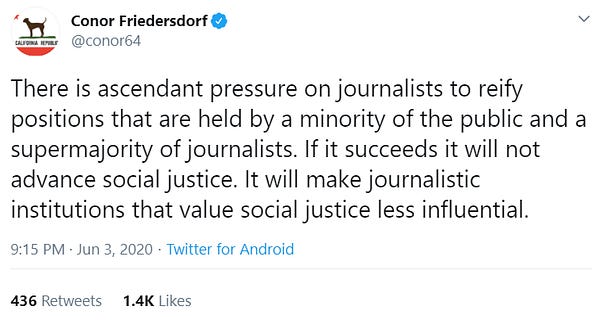

This has been a damaging fad, and a fad reinforced by significant social and professional pressure in left-of-center journalistic and academic spaces: pressure to treat the pro-abolition and pro-defunding positions as gingerly and credulously as possible. In early June, The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf tweeted, “There is ascendant pressure on journalists to reify positions that are held by a minority of the public and a supermajority of journalists. If it succeeds it will not advance social justice. It will make journalistic institutions that value social justice less influential.”

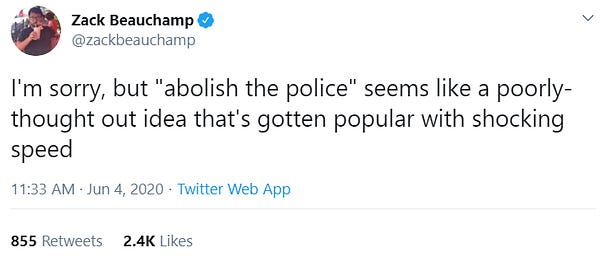

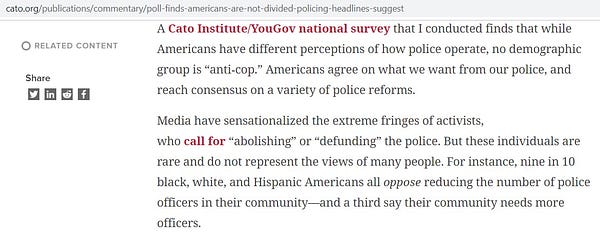

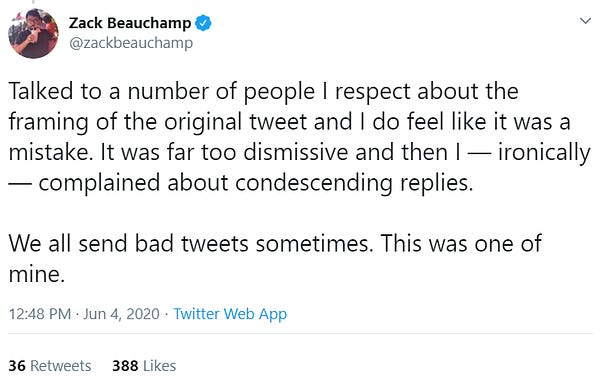

Then, just one day later — you can’t make this stuff up — we saw a remarkable instance of exactly this occurring. Zack Beauchamp, a policy-minded Vox journalist, tweeted, “I’m sorry, but ‘abolish the police’ seems like a poorly-thought out idea that's gotten popular with shocking speed.” He was met with such a rush of opprobrium for questioning this belief from the journalists and activists and academics who constitute the too-online left that he backtracked about an hour later:

Beauchamp’s description of this idea as ‘popular’ is subtly revealing. Police abolition is supported by about 15% of Americans (that’s from a poll conducted in July), meaning it is not just underwater but drifting listlessly somewhere in the Marianas Trench. But, as Friedersdorf’s tweet indicates, that group of 15% or so of Americans is strikingly overrepresented in the circles in which Beauchamp travels. Hence, his false belief that this is a popular position. Hence, his inability to stick to his guns and defend the eminently reasonable position that police abolition is a poorly-thought out idea. Hence, the Times giving disproportionate, pushback-free space to proponents of this and other unpopular views.

Increasingly, mainstream journalism isn’t about representing the country, or unpacking complex issues with fairness and accuracy. It’s about showing that you are on the ‘right’ side. Even if the ‘right’ side represents a tiny sliver of society — mostly your fellow, well-educated progressive friends and colleagues.

(Update: In a few places in this post, including the headline[!], I had originally written “prison abolition” rather than “police abolition.” This has now been fixed.)

Questions? Comments? Grim national survey results about the popularity of Singal-Minded? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The lead image is the cover of The End Of Policing.