That Might Have Been The Strangest Thing That Has Ever Happened To Me On Twitter

A surreal parable about appeals to authority, overconfident dilettantes, and what happens when social media turns important controversies into team sports

Friday was a busy day for me: I woke up in Oakland, recorded a podcast, took a call while cleaning up the tiny house my friend generously let me stay in, lost track of time during said call, rushed to BART convinced I would miss my plane, made the flight, hopped on the flight, landed at The Secret L.A. Airport I Hope People Don’t Find Out About Because It’s Much Easier Than Dealing With LAX If You’re Headed To Certain Parts Of That Area, picked up my rental car, and arrived at the home where my oldest childhood friend lives with his wife and very cute kids. Quite a pleasant evening, at first.

Because I keep the Twitter app off my phone, I had no idea that a controversy was percolating about me. A researcher had accused me of misinterpreting a sentence he himself wrote in the latest Standards of Care of the World Professional Association of Transgender Health. I wouldn’t say this is every science writer’s “worst” nightmare, but it’s a pretty big deal: if you bungle the meaning of scientific language so severely that the author of that language has to swoop in and say “Hey, about that…,” then that’s not a good sign.

Except the error he accused me of making didn’t appear to be an actual error. And his argument was odd. And things got even weirder when I reached out to some of the key experts in the area in question. And… well, I don’t want to get ahead of myself. Let’s just say this turned into one of the absolute strangest things I have ever seen happen on Academic Twitter, and an object lesson in Twitter’s ability to generate bullshit at an exponentially faster rate than anyone can clean it up (also known as Brandolini’s law or the bullshit asymmetry principle).

In this case, at least, there was a very satisfying ending — but we’ll have to back up a bit to get there.

***

On Thursday, New York magazine published a column by my former colleague Jonathan Chait. In it, Chait disagreed with an open letter that a bunch of The New York Times contributors had sent to that paper harshly criticizing its coverage of transgender issues (you can hear my discussion of that letter with Katie Herzog here). Chait argued that there are legitimately difficult issues in youth gender medicine that merit journalistic scrutiny, especially given the mental health problems some American youth are experiencing.

Some of Chait’s colleagues were furious. “I am deeply disappointed and disgusted that my employer @nymag published this in response to the open letters to NYT,” wrote Madeline Leung Coleman, a New York mag editor. “Distorting, wrongheaded, shortsighted, un-fact-checked. And by the way, check out this line!”

Coleman included a screenshot of this whole paragraph from Chait’s piece, and highlighted the part I’m bolding:

Unlike in past years, when “those assigned male at birth accounted for the majority,” a large majority of children questioning their gender now were assigned female at birth, reported Reuters. “Adolescents assigned female at birth initiate transgender care 2.5 to 7.1 times more frequently than those assigned male at birth,” according to WPATH. This is taking place in the context of a mental health crisis that is disproportionately affecting girls and LGBTQ+ teens. Properly assessing kids who question their gender is much more challenging when they are afflicted with serious mental health challenges. And so medical providers are diagnosing and treating kids much faster than before at a time when the patient population has become much harder to diagnose.

If you click here you’ll see that a lot of people quote-retweeted Coleman. It’s a strange experience to read the quote-retweets, because there is almost universal agreement that Chait’s excerpt is egregiously bad — how could someone write something so vile? — and yet there is no unifying theory as to why it’s bad. One of the quote-retweeters was Alice Markham-Cantor, a fact-checker at the magazine, who wrote, “chait please i am begging. let us check your work before you post.”

To those watching this unfold, this direct callout from his own magazine’s fact-checker was obviously seen as quite embarrassing to Chait.1 So again, a lot of quote-retweets mocking Chait for his astounding ignorance. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen someone in media owned this hard,” said one member of the peanut gallery. “Holy shit.”

It was unclear to me what Chait had gotten wrong, so I tweeted “This is causing a whole other uproar at my former employer, but to be clear, what Chait is saying here is *straight from WPATH*. If journos can’t follow WPATH’s lead without getting attacked by their colleagues, coverage of this issue will be impossible. Which is maybe the point?”

And I included a screenshot of the sentence I would soon be accused of misunderstanding, right from the adolescent section of the WPATH SoC: “In some cases, a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicating mental health histories (Leibowitz & de Vries, 2016)), co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics (Strang, Powers et al., 2018), and/or an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence (Ristori & Steensma, 2016).”

From where I sat, this tidily supported Chait’s argument that if far more kids with other mental health problems are seeking youth gender care than used to, we should put a premium on assessment — and on journalistic scrutiny of youth gender clinicians. I also replied to the NY Mag staffers who had been criticizing Chait, linking to my other tweet and saying “genuinely don’t get what a fact-checker would have flagged here -- this is a fairly basic principle of working with kids with GD, straight from WPATH.”

I ignored the replies until now (“That’s because you’re a bigot with an anti-trans agenda,” yadda yadda) and more or less dropped it.

***

Cut to Friday night in my friend’s kitchen in Burbank, where I log on to Twitter and see DMs from Katie strongly encouraging me to respond to the allegations leveled at me that morning — the day after all the Chait stuff happened — by a contributor to the Standards of Care.

The contributor in question is named E. Kale Edmiston, an associate professor of psychiatry and biomedical sciences at UMass Chan Medical School. Edmiston was very angry and very exasperated that I had so badly misinterpreted his work — and that I hadn’t reached out to him before referencing it.

First, he replied to Chait himself: “Hi! I wrote the highlighted sentence in the WPATH SOC8. Just here to say, you are interpreting the SOC8 incorrectly.”

Then Edmiston quote-retweeted Michael Hobbes, a habitual Twitter critic of mine who, in my experience, has a very weak grasp on the basics of this controversy married to very strong and frequently expressed convictions about the shortcomings of journalists who write about it. Edmiston said: “I wrote the sentence Jesse is using and willfully misinterpreting to justify limiting access to care. It is about additional assessment to provide support for trans kids w mental health concerns. It is not about using mental health concerns to deny access to transition.”

Then Edmiston tweeted at me directly: “I’m sure I will regret this” — hold that thought — “but I wrote the highlighted sentence in SOC8. Here to say that your interpretation/extrapolation of it is incorrect.” Next tweet: “[Mental health diagnoses] & access to [hormone replacement therapy] are not contraindicated. This sentence is to ensure that ppl get access to resources if they need them, not to determine if their MH concern is a ‘differential diagnosis’. You have misunderstood my work. Pls correct, as journalistic ethics requires of you.”

Edmiston also expressed frustration at my alleged transphobia and the fact that I didn’t reach out to him before quoting from the SoC: “It is so telling that these anti-trans journalists would quote my work, misrepresent it, but never actually reach out to me to ask me anything.”

I was confused about Edmiston’s accusation from the get-go. For one thing, I couldn’t understand exactly what argument he was making, which is important in a situation like this where you’re accused of journalistic wrongdoing. It was this part I was hung up on: “MX dx & access to hrt are not contraindicated.” The most common sense interpretation is that he is saying that non-GD mental health diagnoses aren’t an automatic contraindication for hormones (or blockers, which are also part of this conversation). But if that was Edmiston’s point, it’s fairly trivial and it isn’t a response to anything myself or Chait have ever written (Chait confirmed this in a Twitter DM), either in the excerpt and tweets in question or anywhere else. If a kid has been carefully assessed as having long-term gender dysphoria, and their internal sense of gender identity appears to be stable, and their other mental health problems don’t seem to be interfering with clinicians’ ability to make a reasonable judgment that blockers or hormones are likely the right move, I’d never argue that the mere presence of those other problems should, on its own, render the kid ineligible for those treatments. So if that’s what Edmiston’s tweet meant, we agree, and I have no idea why I’m being accused of distorting anything.

But Edmiston seems to be making a significantly stronger claim: that other mental health problems are never a contraindication for hormones or blockers. If that isn’t what he’s saying, I don’t know how to interpret this bit: “This sentence is to ensure that ppl get access to resources if they need them, not to determine if their MH concern is a ‘differential diagnosis’.”

This is… bizarre. That’s the only word for it. Let’s look at the original sentence again: “In some cases, a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicating mental health histories (Leibowitz & de Vries, 2016)), co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics (Strang, Powers et al., 2018), and/or an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence (Ristori & Steensma, 2016).” That sentence itself doesn’t explicitly say why a more extended assessment process may be useful, but it’s blazingly obvious that a major reason is the importance of ensuring that what appear to be GD symptoms are, at root, caused by GD rather than other conditions.

It’s obvious for two reasons: first, all three citations point to studies discussing, in one way or another, the possibility of a kid with GD symptoms not having GD or not settling into a long-term transgender identity. Of course it would be irresponsible for a clinician to put a kid on blockers or hormones if they didn’t think the kid had GD or was likely to maintain his or her trans identity.

Maybe this is overkill — I shouldn’t have to do this given that the intent of the sentence is quite clear if you’re at all familiar with this area — but let’s briefly go through one example from each of the three citations:

Determining the relationship between any co-occurring mental health issue(s) and GD is important in determining appropriate treatment interventions. For example, if an adolescent meets criteria for a depressive disorder and GD, it is entirely possible that the depression could be a manifestation of underlying GD. Alternatively, if an adolescent meets criteria for an ASD [autism spectrum disorder] and reports aspects of GD, it might be possible that the ASD complicates the assessment and impairs the adolescent’s ability to understand the differences between gender identity and gender role, or gender identity and sexual orientation.

Could this be any clearer? One goal here is to determine “appropriate treatment interventions,” and of course exploration of co-occurring mental health problems might cause a clinician to rule out physical interventions. If a child who appears to have GD and ASD has developed misunderstandings about the “differences between gender identity and gender role, or gender identity and sexual orientation” — not an uncommon occurrence, you’ll find, if you interview youth gender clinicians — of course that would affect the treatment outlook, because it would, at the very least, call into question whether they actually have GD. Why wouldn’t you at least delay the hormones discussion until you’re sure that the child can sufficiently distinguish between gender identity, gender roles, and sexual orientation? You’d be negligent to do anything but that — this is what experts mean when they talk about the importance of “a more extended assessment process” in some instances.

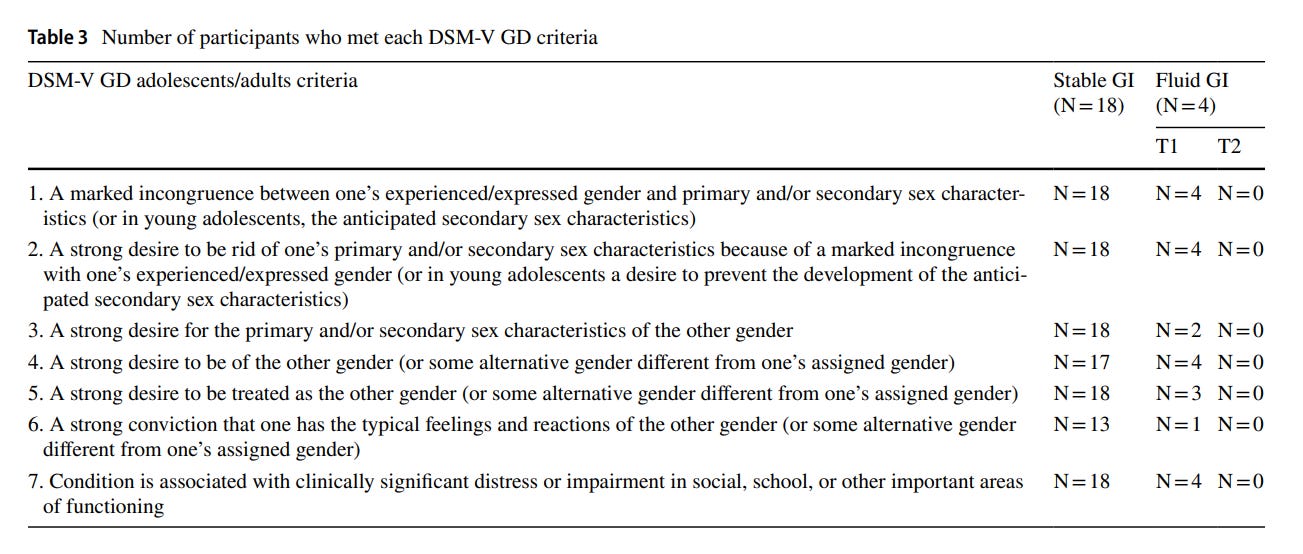

Second citation: Strang, Powers et al., 2018 drew on the results of interviews with 22 “gender-diverse” adolescents with autism to get their perspectives on transitioning and other issues. It includes a chart showing that there was some fluctuation, over the course of the ten months between the study’s two post-baseline check-ins, in whether the kids qualified for a DSM-5 GD diagnosis. Specifically, four of the 22 adolescents went from meeting the criteria to not.

To be clear, these were highly dysphoric kids at baseline — all initially met the DSM criteria. This study shows that in some cases, their GD symptoms abated over time. (This shouldn’t surprise anyone who knows anything about young people, the debate over youth gender transition, or both.) And it’s noteworthy that “Before their shift in GD, three of the four participants with attenuating GD had requested medical gender treatment and two of them had completed an initial consultation with a medical gender specialist.” This study is being cited, in part, for exactly the reason Edmiston is saying it isn’t being cited: to show that sometimes, if a child with GD symptoms also has other mental-health conditions, that is a reason to pursue physical transition cautiously.

Finally, the third article cited, Ristori & Steensma, 2016, which is tied to the phrase “absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence,” is almost entirely about kids who do have childhood GD, and it focuses heavily on the questions of which kids will persist (continue experiencing GD) versus desist (the GD will abate on its own, even without transition). (If you ask around, some people will confidently tell you that desistance hardly ever happens, or is a “myth” entirely, but I’ve written at length about why this argument doesn’t make sense.) It includes a line mentioning that in one sample, “Both persisters and desisters stated that the changes in their social environment, the anticipated and actual feminization or masculinization of their bodies, and the first experiences of falling in love and sexual attraction [from ages 10 to 13], contributed to an increase (in the persisters) or decrease (in the desisters) of their gender related interests, behaviours, and feelings of gender discomfort.” Basically all the evidence we have about youth gender transition comes from samples whose GD began in childhood, and puberty is thought to be an exceptionally important period for the solidification of gender (and other forms of) identity. I think the point of this citation is simply that with adolescent-onset cases of GD, clinicians are flying much more blindly than they are with childhood cases (me editorializing: not that the evidence there is great either), which is therefore more reason for caution.

The citations clash wildly with Edmiston’s argument, is the long and the short of it. As far as I can tell, there is nothing in any of them to support his argument that I misinterpreted this sentence. To believe I misinterpreted it the way he claims I did, you would have to believe that the intent of the sentence is to say that if a kid has GD and (say) ASD, you just treat those two things on separate tracks and don’t explore the possibility that the latter is causing — or giving the illusion of the presence of — the latter former. After all, “This sentence is to ensure that ppl get access to resources if they need them, not to determine if their MH concern is a ‘differential diagnosis’.” Well, it’s not an either/or — in-depth assessments perform both functions! Edmiston’s reading of his own sentence appeared to be prima facie ridiculous. Which was odd, to say the least.

Even if we didn’t have these citations, we’d have the rest of the adolescent chapter of the Standards of Care, which is replete with examples that, again, point in the exact opposite direction as Edmiston’s claim. I laid them out in some tweets (archived) I sent to Edmiston when I was trying to figure out what was going on here.

There’s this, for example:

The most robust longitudinal evidence supporting the benefits of gender-affirming medical and surgical treatments in adolescence was obtained in a clinical setting that incorporated a detailed comprehensive diagnostic assessment process over time into its delivery of care protocol (de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; de Vries et al., 2014). Given this research and the ongoing evolution of gender diverse experiences in society, a comprehensive diagnostic biopsychosocial assessment during adolescence is both evidence-based and preserves the integrity of the decision-making process. In the absence of a full diagnostic profile, other mental health entities that need to be prioritized and treated may not be detected. There are no studies of the long-term outcomes of gender-related medical treatments for youth who have not undergone a comprehensive assessment. Treatment in this context (e.g., with limited or no assessment) has no empirical support and therefore carries the risk that the decision to start gender-affirming medical interventions may not be in the long-term best interest of the young person at that time.

That seems to pretty clearly argue for clinicians to understand GD, other mental health problems, and the question of whether medical transition is the right move as all being interrelated.

Elsewhere in the chapter, the authors write, “We recommend health care professionals assessing transgender and gender diverse adolescents only recommend gender-affirming medical or surgical treatments requested by the patient when.… [among many other criteria] The adolescent’s mental health concerns (if any) that may interfere with diagnostic clarity, capacity to consent, and gender-affirming medical treatments have been addressed.” “Diagnostic clarity” here simply means, again, attending to the possibility that symptoms that appear to point to a diagnosis of gender dysphoria aren’t being caused or exacerbated by something else (such as the aforementioned example involving an ASD diagnosis, or perhaps anxiety and OCD in a teenage girl manifesting as obsessive thoughts about her body that she or her parents wrongly interpret as GD). If you don’t ask these questions, you might nudge a kid ahead to serious medical treatments — treatments for which we have shockingly little good evidence — without having ruled out other possibilities. Given that Reuters contacted 18 youth gender clinics and couldn’t find any doing careful, in-depth assessments prior to approving kids for these treatments, surely this is worth discussing!

Perhaps most straightforwardly, part of the adolescent chapter discusses the specific reasons why co-occurring mental health problems “may challenge the assessment and treatment of gender-related needs of [transgender and gender-diverse] adolescents”:

First, when a TGD adolescent is experiencing acute suicidality, self-harm, eating disorders, or other mental health crises that threaten physical health, safety must be prioritized. According to the local context and existing guidelines, appropriate care should seek to mitigate the threat or crisis so there is sufficient time and stabilization for thoughtful gender-related assessment and decision-making. For example, an actively suicidal adolescent may not be emotionally able to make an informed decision regarding gender-affirming medical/surgical treatment. If indicated, safety-related interventions should not preclude starting gender-affirming care.

Second, mental health can also complicate the assessment of gender development and gender identity-related needs. For example, it is critical to differentiate gender incongruence from specific mental health presentations, such as obsessions and compulsions, special interests in autism, rigid thinking, broader identity problems, parent/child interaction difficulties, severe developmental anxieties (e.g., fear of growing up and pubertal changes unrelated to gender identity), trauma, or psychotic thoughts. Mental health challenges that interfere with the clarity of identity development and gender-related decision-making should be prioritized and addressed.

In light of all this, I found it absolutely baffling that Dr. E. Kale Edmiston, a coauthor of this chapter, was accusing me of misinterpreting the sentence in question. The evidence to the contrary was overwhelming. I also noticed something strange: Edmiston wasn’t listed as a coauthor on the adolescent chapter of the Standards of Care. Rather, he worked on the adult chapter, which had nothing to do with the dispute at hand. (The Standards of Care is released as a single publication with a large number of authors, but the chapters are written by independent teams composed of experts from different specialties. The coauthors of the “Hormone Therapy” chapter are endocrinologists, and therefore wouldn’t have the expertise to write the “Assessment of Adults” chapter — more a matter for psychologists — and vice versa.)

What was going on here? In addition to the tweets I tagged him into, I sent Edmiston an email Friday night in which I raised these issues and inquired about his absence from that list of coauthors. I sent some other emails, too. We’ll get to those.

***

To many people on Twitter, “what was going on here” was that I’d been exposed — yet again — as an abject fraud, a transphobic hack. The denizens of this corner of Twitter were jubilant. Woody Allen and Marshall McLuhan came up repeatedly.

Jeet Heer of The Nation demanded Chait and I answer the charges: “I would like Jesse Singal & Jon Chait to respond to the fact that a scientist they quoted is saying his work is being misinterpreted.”

Hobbes was disgusted that I was pushing back on Twitter and asking Edmiston to reconcile his claim with the text of the chapter he coauthored. “Carry yourself with the confidence of Jesse Singal lecturing a researcher on how to interpret his own work,” he tweeted.

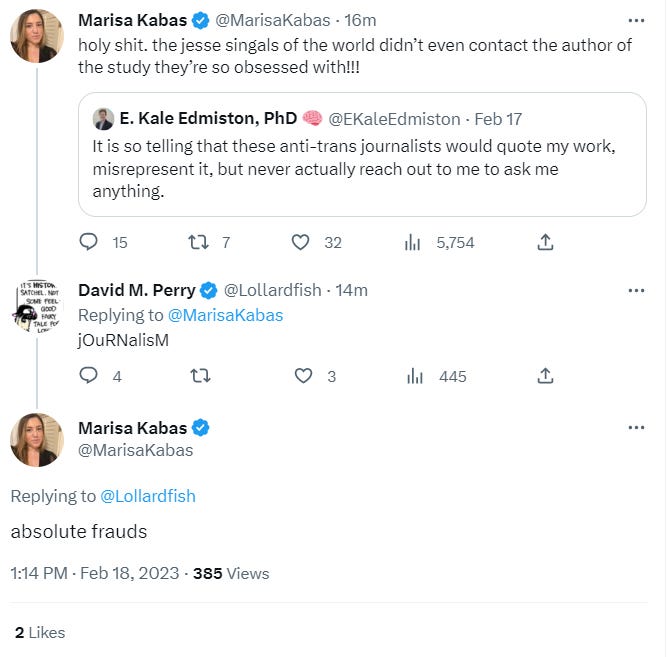

Marisa Kabas, a columnist at MSNBC, was gleeful: “holy shit. the jesse singals of the world didn’t even contact the author of the study they’re so obsessed with!!!” (It’s not a study.) Then: “the fucking gall of the anti trans ‘journalists’ to criticize the writers who signed the NYT letter.”

“jOuRNalisM,” replied David Perry, a truly raving lunatic even by the standards of Twitter, who once tried to pressure a journalist to leave a listerv simply because I was also on it (get a hobby, Davey). “absolute frauds,” responded Kabas.

Eric Vilas-Boas, a Vulture staffer, quote-retweeted Kabas and said: “they know that doing so [contacting the author] would dismantle their lazy, house-of-cards arguments. simple as that.”

Miles Klee, who is some sort of freelance writer, chose to communicate his triumph at my humiliation with a billiards metaphor: “cleared. rack em. god damn lol.”

Siva Vaidhyanathan, a professor of media studies and podcast host, wrote: “I really thought @jessesingal and @jonathanchait were responsible journalists, willing to cite and quote in good faith. Instead, they seem to be careless at best, malevolent at worst. How could they care so little about their reputations?”

A ton of people, it turned out, had pinged me while I was making my way from the Bay to Burbank, demanding I respond to this allegation. “It’s been nine hours so far, and Singal still hasn’t responded,” someone tweeted right around the time I was parking the rental car in Burbank. “I wonder what he’s waiting for.” When I saw that tweet, I pointed out, a bit impatiently, that I’d been away from Twitter all day. One user, after (I would like to think) unfurling a giant cloth map of California on his kitchen table, blowing the dust off it, staring intently at it, and making various calculations with a protractor, insisted I must have been lying: “You flew from SF to LA that's less than 2 hours. You either saw this or people let you know and you spent hours thinking of your response.” (No, I was in line at Thrifty.) We were getting dangerously close to Pepe Silvia territory.

Twitter is always going to Twitter, and there’s no floor to the laziness and stupidity of its worst denizens, but I still found it baffling that on Friday and into Saturday, so many people spent so much time arguing that the adolescent chapter of the WPATH Standards of Care didn’t say exactly what it does say. Because everyone took it at face value that Edmiston was right, no further investigation was required: clearly, I had made a profoundly embarrassing blunder. Their prior beliefs about me — that I was a horribly transphobic idiot — surely sped them along toward this conclusion.

Luckily, despite my many other shortcomings, I had a leg up on my critics: I’ve actually reported on this issue at length, and have spent a lot of time talking to some of the coauthors of the adolescent chapter. That’s who I emailed. I woke up to a reply from Scott Leibowitz, one of the chapter’s two co-chairs, that read, in part: “I have never heard of that person in my life until this chain, and that sentence was certainly not written by them whatsoever.”

***

In the morning I emailed Edmiston a second time. This one was shorter. I pasted in Leibowitz’s quote and said I was going to publish it, and that he should call me in the next hour if he wanted to comment. None of my queries to Edmiston got a response: not the original tweets highlighting the parts of “his” chapter that conflicted with what he was saying, not either of the emails, not a final email I sent asking him to clarify one of his tweets for this post.

With no word from Edmiston, I tweeted: “Dr. E. Kale Edmiston said I misinterpreted a sentence in the WPATH SoC he himself wrote. I reached out to Scott Leibowitz, co-chair of the chapter in question: ‘I have never heard of that person in my life... and that sentence was certainly not written by them whatsoever.’ [shrug emoji]”

Twitter went berserk. This was a bizarre outcome — a complete reversal. Everyone treated it like a football game where one team had come back from down 20 points in the fourth quarter to win on a last-second field goal. Things got worse for Edmiston when Leibowitz himself made a rare twitter appearance to quote-retweet one of Edmiston’s claims that I was lying. He wrote: “In this era, it feels normal to expect mistruths to come from politicians. So when they come from our fellow academic colleagues, it’s unfortunate and undermines the trust in the integrity of the work. Here is an accurate list of the @wpath #soc8 authors: [link to this].” (To be clear, I did not and would not ask Leibowitz to chime in in this manner on Twitter — I first found out about it when someone pointed me to his tweet.)

I’m slightly ashamed to say that I actively participated in the revelry. It was all extremely cathartic, if I’m being honest. Ever since I have started writing about this issue, a subset of genuinely immoral people in academia and media have tried very hard to lie about my writing on this subject and, in some more extreme cases, destroy my reputation with straightforwardly defamatory claims. My work is by no means perfect or above critique, and I’ve made mistakes, but there’s a chasm that’s light years wide between what I’ve written and what a subset of my critics insist on maliciously and performatively pretending I’ve written.

Could anything better symbolize this than an academic popping up to wrongly accuse me of misrepresenting his work, and of not reaching out to him beforehand, only for it to turn out that he didn’t even write the thing he claimed to have written? Over and over, I tweeted at the people who had jumped on the bandwagon against me, demanding deletions and apologies (my batting average wasn’t great on the apologies front). It was not a good use of my time, and of course my lack of grace here certainly didn’t improve the overall Twitter climate on this issue (and so many others): the debate over youth gender medicine really is treated like a team spectator sport rather than a matter requiring humility, nuance, and compassion. My “enemies” were thrilled that I had been humiliated, and they performed the online equivalent of beating up a me-shaped piñata, and then my “allies” were thrilled at the dramatic turnabout and gave Edmiston the same treatment.

I’m certainly not saying that my actions and his were equivalent; he was the aggressor, he publicly launched a false accusation at me, and he badly misrepresented his role working on the WPATH SoC. Rather, I am saying that the hysterical pitch of Twitter exacerbates everything, and that I threw fuel on the fire because I was so tired of years of defamatory bullshit and had finally achieved the sort of nigh-indisputable, 120-decibel vindication I’d often longed for during these profoundly asinine blowups.

So did Dr. E. Kale Edmiston simply lie about having written a sentence he didn’t write? If he did, it would be an unbelievably self-destructive act. He’s offered two explanations since this all popped off. First, Edmiston replied to Leibowitz: “Hi Scott! I dm’d you, I’m sure you forgot, but we were on a call together to hash out shared language btwn the adol & adult ch last year- I called in w/o video- that might be why you don’t remember me. I’d appreciate it if you’d correct bc I’m getting harassed & so is my employer.” Next tweet: “I did my dissertation in adolescent autism which is why I weighed in on the topic.”

People use terms like “last year” loosely, but if Edmiston means “in the year 2022,” this explanation makes no sense, because there’s a draft version of the adolescent chapter dated December 2021 which already contains the language he claims he wrote:

He told a similar story to Michael Hobbes in direct messages that Hobbes posted: “There’s a lot of authors and we don’t all know each other. If you look at the document I am an author. We work closely with a few people on specific sections. I don’t know Scott either.”

Edmiston also told Hobbes: “Ok, actually I do think he was on the phone call where we hashed out this autism issue- it was an audio call so he might not remember me. The adolescent and adult assessment chapters were written in part together to ensure consistency between chapters.”

Of course, this whole thing started when Edmiston said he authored one specific sentence in the adolescent section — a sentence the co-chair of that chapter insisted, to me, he didn’t write. Even if he was on a call with Leibowitz, of course that doesn’t mean he wrote the sentence in question, which must have gone through numerous drafts and back-and-forths between the listed members of that particular committee. Edmiston’s mention of his dissertation subject also doesn’t make sense here: the sentence in question was much broader than that, and autism was only one of a number of potentially complicating factors mentioned in it. “[W]e hashed out this autism issue” — how could the sentence in dispute, which is mostly not about autism, be the result of hashing out an autism issue?

Edmiston told a slightly different story after a Twitter user, responding to Hobbes’ posting of his chat logs with Edmiston, said:

Another point to consider:

Both of those Chapters have the same Lead Chair (Jon Arcelus).

Isn’t it possible that he used language from one of the chapter 7 writers in chapter 6 without specific attribution?

To which Edmiston responded: “This is it. I wrote the corresponding sentence in the adult ch, Jon shared drafts of the chapters btwn teams, highlighting where there were discrepancies. The lang in the adolescent ch was changed to what I wrote for adults in this instance. I had minimal contact w Scott directly.”

Arcelus is listed as a “co-chair liaison” for a number of chapters, including the two in question. Presumably, this means he coordinated between the chapters when necessary. To the extent I can follow any of this, Edmiston appears to be saying that he wrote a sentence on this subject for the adult section, there was some discrepancy between his language and similar language in the adolescent section, and the dispute was resolved by the adolescent section adopting his language. (Arcelus didn’t return an email seeking comment and/or clarity.)

There does appear to be one pair of sentences expressing a similar sentiment in both chapters, but when you look at them, Ediston’s argument still doesn’t really make sense.

Adult: “For TGD adults with a complex presentation or for those who are requesting less common treatments or treatments with limited research evidence, more comprehensive assessments with different members of a multidisciplinary team will be required.”

Adolescent: “In some cases, a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicating mental health histories (Leibowitz & de Vries, 2016)), co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics (Strang, Powers et al., 2018), and/or an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence (Ristori & Steensma, 2016).”

These are still pretty different sentences — the adolescent sentence mentions three different issues (“complicating mental health histories,” “co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics,” and “and/or an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence”) that are nowhere to be found in the adult sentence. Even if, as Edmiston claims, “The lang in the adolescent ch was changed to what I wrote for adults in this instance,” clearly significant changes occurred after that, or else how did all that extra stuff get in there?

The absolute most generous interpretation of what happened, if we grant that Edmiston did write the sentence from the adult section (which, to be clear, I’m not granting), is that some language was ported over from the adult to the adolescent section, but then the adolescent team made significant major alterations to the sentence to insert issues that apply specifically to adolescents and to their own research and assessment interests.

On top of this, if Edmiston did write the sentence in the adult chapter, and did intend for it to have the meaning he claimed on Twitter (no need for differential diagnosis, no need to consider how other mental-health conditions might complicate a gender dysphoria diagnosis or be a contraindication for blockers or hormones), then he is in severe disagreement with… himself.

Here’s one of the criteria listed in the adult chapter under “We recommend health care professional assessing transgender and gender diverse adults for gender-affirming treatments”:

Statement 5.1.c

Are able to identify co-existing mental health or other psychosocial concerns and distinguish these from gender dysphoria, incongruence, and diversity.

Gender diversity is a natural variation in people and is not inherently pathological (American Psychological Association, 2015). However, assessment is best provided by an HCP [health care professional] who possesses some expertise in mental health in order to identify conditions that can be mistaken for gender incongruence. Such conditions are rare and, when present, are often psychological in nature (Byne et al., 2012; Byne et al., 2018; Hembree et al., 2017).

The need to include an HCP with some expertise in mental health does not require the inclusion of a psychologist, psychiatrist, or social worker in each assessment. Instead, a general medical practitioner, nurse, or other qualified HCP could also fulfill this requirement if they have sufficient expertise to identify gender incongruence, recognize mental health concerns, distinguish between these concerns and gender dysphoria, incongruence, and diversity, assist a TGD person in care planning and preparation for GAMSTs [gender-affirming medical and/or surgical treatments], and refer to a mental health professional (MHP), if needed. As discussed in greater depth in the mental health chapter, MHPs have an important role to play in the care of TGD people. For example, the prejudice and discrimination experienced by some TGD people (Robles et al., 2016) can lead to depression, anxiety, or worsening of other mental health conditions. In such cases, an MHP can diagnose, clarify, and treat mental health conditions. MHPs and HCPs with expertise in mental health are well-placed to assess for GAMSTs, as well as to support TGD people who require or request mental health input or support during their transition. For additional information see Chapter 18—Mental Health.

So Edmiston himself coauthored language pointing out that, when indicated, clinicians in trans healthcare can both use the concept of differential diagnosis to ensure physical transition is the correct path forward and provide extra support for folks who both have GD and other mental health condition. Then he claimed I was misinterpreting language from a different chapter that was basically saying just that.

There is simply no way a good-faith person can come away from all of this believing that “I wrote the highlighted sentence in the WPATH SOC8,” “I wrote the sentence Jesse is using and willfully misinterpreting to justify limiting access to care,” and “I wrote the highlighted sentence in SOC8” are true statements on the part of Dr. E. Kale Edmiston. (I sent WPATH a couple requests for comment and heard back Monday. The email read in part: “The Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8, was developed by 119 authors. It is WPATH’s intent that through the process of rigorous review of all evidence and ideas, the SOC8 Revision Committee will reach consensus on guidelines that can hold up to scrutiny within health science and human rights standards, and that will benefit the people they are meant to serve on a global level. The use of a Delphi process [my link] to reach agreement on the recommendations among SOC-8 committee members. No one person is responsible for a single sentence or chapter, it was a collaborative consensus document among leaders in the field of TGD health.”)

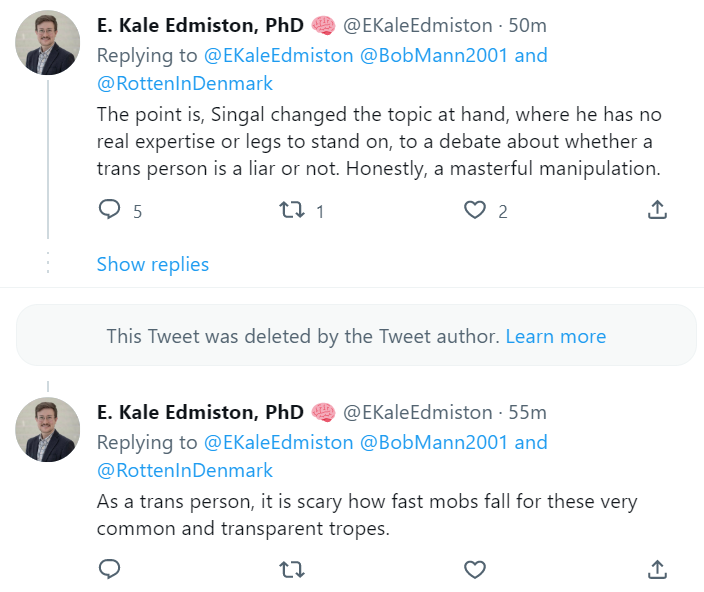

Edmiston, for his part, has a theory about why he received so much heat online this weekend: transphobia. “The point is, Singal changed the topic at hand, where he has no real expertise or legs to stand on, to a debate about whether a trans person is a liar or not. Honestly, a masterful manipulation.” And then: “As a trans person, it is scary how fast mobs fall for these very common and transparent tropes.”

I had no idea he was trans until we were well into this mess, and of course I’m not directing my ire at “a trans person,” but rather at a specific doctor who launched false accusations against me publicly, demanding I correct a perfectly accurate reference to an unambiguous sentence he wrongly claimed to have written.

But whatever else is going on here — and I am guessing we’ll have a bit more information soon — details don’t appear to be Edmiston’s strong suit.

Questions? Comments? False claims of authorship? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

Image: “Burning rubbish dumpster in city, next to the full container rubbish is lying on the street” via Getty. I wanted to ask DALL-E to produce art responding to the prompt “a field of burning dumpsters as far as the eye can see, cyberpunk style,” but alas, the site was down.

It also makes New York magazine seem like a complete basket case of an institution — of course if a fact-checker thinks an error has been made he or she should contact the appropriate editor so they can issue a correction, rather than make a public spectacle of it that seeks to inflict maximum embarrassment on the writer responsible for the error.

I just want people to know that I, not Jesse, wrote this entire post.

OK, well, I didn't exactly *write it* write it, but I outlined its structure and main points, and let Jesse fill in the details.

Or, to be a little more precise, I didn't actually have any contact with Jesse, who doesn't know that I exist. But I did follow the Twitter battle as it was playing out, and thought of some snappy retorts that I thought Jesse could use. I telepathically conveyed these to him. So BASICALLY I'm the author of the long post that resulted.

Jesse's utter lack of journalistic integrity is shown by the fact that he did not cite or credit me in any manner whatsoever for my vital contributions. Harumph.

I know we all live and die by “lived experience” now, but doesn’t there seem to be just a little bit of a conflict of interest when trans people are all over the major studies and standards regarding transgender care?