Please Stop Sharing This Viral But Misguided Free-Speech Comic (Unlocked)

xkcd is great but it really whiffs on this one

My subscribers voted, overwhelmingly, that they are okay with me sometimes unlocking previously paywalled posts that are at least three months old. That’s what I’m doing here — this post ran on 8/23/2019, and the original version lives here. As always, I’m cloning it to protect the privacy of subscribers who commented on the original — this version was created on 6/9/2021.

If you find this article useful or interesting, please, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. My paid subscribers are the reason I was able to write this piece in the first place, and they’re the ones who keep this newsletter going.

I. Love. xkcd.

Before proceeding, I just want to be clear about that. I have been reading xkcd, a wildly successful webcomic that has spun out into books, giant interactive events, and basically a whole weird and wonderful internet subculture, forever. The guy who does it, Randall Munroe, is a genius and will rightfully be viewed as an important internet pioneer.

There are, as of this typing, two thousand, one hundred and ninety-two xkcds. Munroe has been doing this for a long time! Here’s the most recent one, which is great:

If you just go to xkcd.com and hit the ‘random’ button you will find hours and hours worth of great stuff (though, fair warning, some of the comics require being a bit of an internet nerd to fully understand them). It’s my favorite webcomic by a large margin.

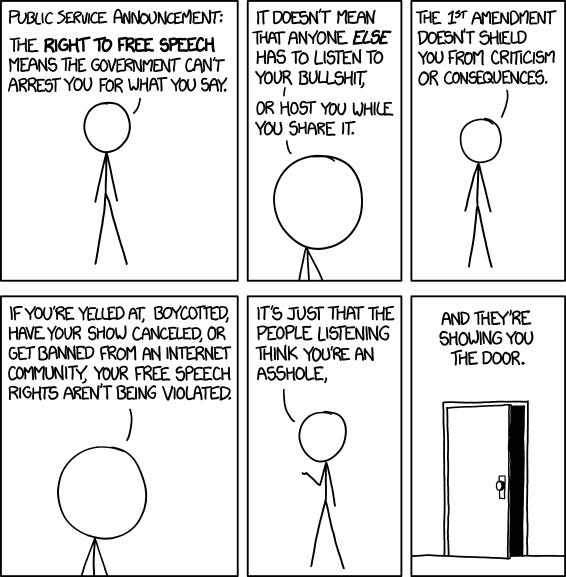

That said, one of the most popular xkcds — and definitely one of the ones with the longest shelf life — has always bugged me. It’s this one, which, if you search its URL on Twitter, you will see that people continue to approvingly tweet out just about each and every day:

Okay, so right off the bat, in the first panel, Munroe is pretty severely understating the scope of the First Amendment and the thick forest of jurisprudence that has sprouted around it: There’s of course a lot more to American free-speech law, at this point, than the government simply not being able to arrest you for saying stuff. To take an example I’m pretty familiar with, the right to free speech has been held, by the courts, to greatly restrict which actions public universities can take in their disciplinary and funding decisions pertaining to student speech, in situations which involve no threat of jail time or direct government punishment (at private universities it’s more complicated).

But that’s a nerdy side-point. My main gripe with this comic, and the reason that it annoys me so many people think it presents a laudable and common-sense understanding of free speech, is the extent to which it confounds discussions of free-speech law with discussions of free-speech norms.

It is definitely true that no one “has to listen to your bullshit. Or host you when you share it.” But it is only a very small and very under-informed segment of the population whose members believe that when Twitter bans someone, for example, the tech giant is committing a literal violation of the First Amendment. For many of us, the conversation is a lot more nuanced than that. We’re interested in questions like: Under what circumstances should someone be banned from Twitter? To what extent do we want a company like Twitter making decisions about who does and doesn’t have a voice on what is (unfortunately) a very influential platform, at a time when social media is (unfortunately) extremely important to the national discourse? More broadly, when do we want it to be acceptable for someone’s livelihood or social ties or whatever else to be genuinely threatened because of their public utterances?

Many of these questions are difficult and involve tradeoffs. The sentence “If you’re yelled at, boycotted, have your show cancelled, or get banned from an internet community, your free speech rights aren’t being violated” references all sorts of different behaviors and outcomes. Getting yelled at is a temporary annoyance or source of fear. Getting banned from an internet community, if it’s one that you have close or longstanding ties to, can be a pretty big deal. Getting your show cancelled can be a very big deal if that’s your livelihood.

When do we want to consider it okay, as a society, to yell at someone or boot them from an internet community or cancel their show? What manner of speech qualifies? The comic strip misdirects by pretending the only question here is whether there are any legal issues with these sorts of behaviors, which there almost always aren’t. This ties into a common tendency I’ve called out in many lefty free-speech takes to swap out difficult questions for easy ones and then pretend the underlying issues have been addressed. It’s easy to replace a difficult question — When should someone be banned from Twitter? — with an easy one: Is it literally a violation of the First Amendment for Twitter to ban someone?

Let’s make all this a bit more concrete. Let’s say that overnight, Twitter, Facebook, the company that hosts my personal website, and my book publisher are all taken over by staunchly anti-abortion figures. They see that I have written in favor of abortion rights, and they’re outraged — they have deep, profound beliefs about the wrongness of abortion. They decide, one by one, that because I’m in favor of abortion access, I shouldn’t have a personal website (at least one hosted by their company), or a Facebook account, a Twitter account, or a book deal. I publicly protest and they all respond by sending me the above xkcd comic.

If we take the comic’s general argument at face value, what have they done wrong? They all really and truly “think [I’m] an asshole” by supporting abortion access, and are “showing [me] the door.” They don’t want someone spouting ideas as poisonous as mine on their platforms. As a result, my platform and future plans shrink significantly, doing permanent damage to my career.

Intuitively, it feels like there should be a coherent response to this that explains why what they are doing is wrong. But it can’t just boil down to “Well, abortion access is legitimately important, and they’re wrong about that issue,” because that’s the very source of disagreement — it’s naive to pretend there aren’t people who really and truly think abortion is wrong and who would, perhaps if they had more cultural power, gladly squelch pro-choice voices.

That’s why we need to talk norms. The comic errs because it treats it as automatically shrugworthy when potentially restrictive free-speech norms are enacted, but without engaging at all with the questions of what process led to the institution of those norms, whether those norms are fair, whether it might sometimes do more harm than good to ban execrable speech, and so on. I am absolutely positive that in the hypothetical case conjured by this comic, Munroe is referring to far-right viewpoints, and of course few of us — not even a relative free-speech purist such as myself — is going to lose much sleep over, say, a hardened Nazi losing his Twitter account. “The First Amendment doesn’t shield you from criticism or consequences,” sure.

But if you look around you will see a lot of people trying to punish a lot of people over all sorts of different speech, the vast majority of it not nearly at the level of Nazi propaganda. Humans are tattle-tales — there is perpetually some professor somewhere facing public outrage and professional sanction for an utterance one half of the country finds utterly anodyne, or at least nowhere near worthy of punishment. So arguably the most interesting free-speech debates center not on the law, but on what sort of world we are going to build, especially now that so many private citizens have extensive records of their views online. Do we want a world in which I can get fired for saying something 50% of my countrypeople agree with? Or 40% or 30%? What would that do in the long run?

I do think liberals and leftists should have a bit of humility on these issues. We should recognize that while we do, in a very real way, dominate most cultural and educational institutions (even if we’re pathetic at gaining political power), you never know who will control things tomorrow. Even just pragmatically — even if you disagree with me and my boring old-school liberal beliefs about free speech — you should understand that the more we promote norms that saying the wrong thing can get you fired or ostracized, the more we’re playing with fire.

That’s what this comic leaves out.

Questions? Comments? Legally questionable claims that this very newsletter constitutes hate speech because it doesn’t come down hard enough on hate speech? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.