Navigating Online Controversy In An Age Of Unrelenting, Exhausting, Ubiquitous Bullshit: The American Dirt Story (So Many Exciting Updates!)

¡No es bueno, periodistas!

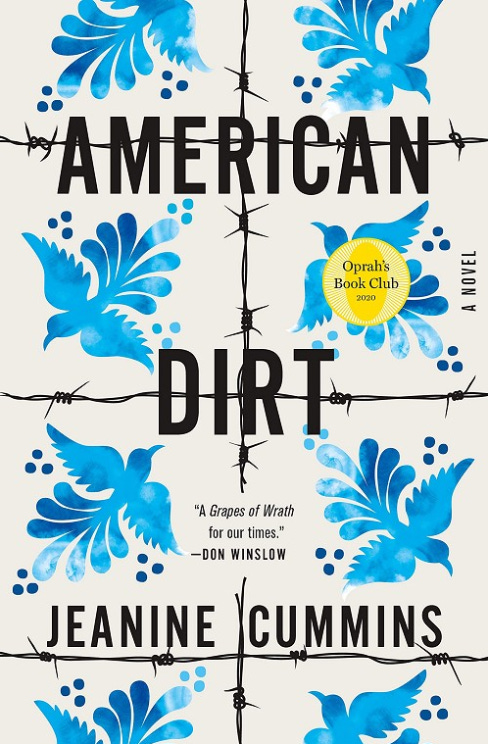

There were certain problems with how American Dirt, the novel by Jeanine Cummins that is currently one of the hottest-selling titles on Amazon, and which was chosen by Oprah for her super-famous book club, was written and publicized.

But how severe were those problems? And which of them were actual, you know, problems, rather than the inevitable outrage-overgrowth that instantly sprouts, kudzulike, during any sort of online pileon, suffocating reasoned conversation?

If you read most journalistic coverage of this controversy, you will not be informed. If anything, you will end up more misinformed than you were when you started. And that’s a useful problem to explore given where journalism is right now. I haven’t read American Dirt, so I can’t speak directly to the plot. But the book itself isn’t actually the point I’m interested in: Rather, I want to talk about the nature of how this controversy — and seemingly every controversy, these days — is being covered by mainstream media outlets.

We will need the plot basics at least, I suppose: As Huffington Post puts it in an article I will soon return to cantankerously, American Dirt “describes the journey of Lydia Quixano and her son, Luca, as they flee drug traffickers and cross Mexico on La Bestia,” an infamously dangerous Mexican freight train migrants use to convey themselves north.

It’s worth starting from the baseline that many, many people like this book. That is suggested both by the sales numbers and by the fact that even among Latino members of the literary elite, there is by no means a consensus that, as some have claimed, it is a harmful or deeply insensitive work. As Laura Miller pointed out in one of the few competently-written and informative articles about this controversy, “American Dirt arrived in reviewers’ hands embellished with endorsements from such revered Latina literary figures as Dominican American Julia Alvarez and Mexican American Sandra Cisneros, writers who either missed or weren’t bothered by the glaring flaws decried by [others].”

I was curious whether this blowup was similar to some of the young-adult-fiction controversies I’ve written about, in which there was almost no there there. In those cases, outraged members of the YA Twitterati twisted random lines or excerpts from books they were determined to hate beyond recognition, sometimes misinterpreting them badly or violating basic rules of reading comprehension, premising their criticisms on theories like “If a racist character expresses racist sentiments, that means the book is racist” that wouldn’t pass muster in a fourth-grade classroom. (As always, see Kat Rosenfield’s piece for the best rundown of all this.) Many YA writers told me that these pileons had a deeply pernicious impact on them, particularly in the case of young writers of color who feel certain pressures to conform more keenly than anyone, and who are sometimes told by white editors who have never faced racism and oppression that in order for their stories to be marketable, they must write about racism and oppression.

So, anyway, I read some of the coverage of the American Dirt dustup, hoping to better understand what was happening, because my gut impulse was there was at least some there worth extracting and understanding, even if it was at the bottom of a large, stinky pile of internet bullshit. And almost as soon as I started, I realized I couldn’t really trust most of what I was reading, because all it was doing was presenting a too-lightly curated version of “people on the internet are saying...,” with the people in question often leveling critiques about as sophisticated and thoughtful as, well, “If a racist character expresses racist sentiments, that means the book is racist.” Or the author of a given piece him- or herself was making these sorts of arguments. In other words, these articles were contributing to and amplifying the bullshit, not joining me, hand in hand, facemasks snugly secured, to help me dig through it in search of something worthwhile — which is what journalism is supposed to do!

Let me give you some concrete examples.

BuzzFeed: “There’s A Lot Of Controversy Around The New Novel ‘American Dirt.’ Here's Everything You Need To Know About It.” Seems useful! Some of the claims in the article, written by Clarissa Jan-Lim, seem straightforwardly legitimate. It’s definitely strange, to my mind, that Cummins appeared to have changed her racial self-identification from white to Latina right around the time the book came out. (To be clear, I think it’s ridiculous to spend much time fixating on the race of the author of a work of fiction, but in fiction publishing it’s a very big deal because of how many people in that industry have adopted a deeply identitarian approach.) I also agree that it’s quite tacky, and a bit offensive, for Cummins’ publisher to have used the barbed wire from the book’s cover as a decorating motif at a release party. Cummins also published a social-media post of a barbed-wire design on her nails — which, again, tacky and a bit offensive, though in my view reasonable opinion can differ as to whether it’s worse than a misdemeanor. (Update: Scratch that — not her nails. A reader writes in to explain that “those aren't Jeanine Cummins' nails in the barbed wire manicure picture. They belong to a twitter person called @bookmanicurist who (as you might surmise) paints her *own* nails to look like book covers; she posted the pic and Cummins retweeted it.” So she caught flack for the retweet, not for anything she did to her own nails. Apologies for the confusion.)

But the article also includes third-party claims that don’t stand up to much scrutiny, and they are presented rather credulously:

David Bowles, a Chicano writer and professor, called American Dirt “harmful, appropriating, inaccurate, trauma-porn melodrama” in a withering review. He also took issue with the use of Spanish words in the dialogue, writing, “Actual examples of Spanish are wooden and odd, as if generated by Google Translate and then smoothed slightly by a line editor.”

Let’s click over to the essay in question, titled “Cummins’ Non-Mexican Crap.” Some of the critiques there are, again, valid and substantive, like the clunky way the novel uses Spanish. Sure, fine. But elsewhere the essay makes really radical claims that most people would disagree with. The very first specific ‘problem’ Bowles lists, for example, is that “Cummins has never lived even within five hundred miles of Mexico or the border.” Hmmm… is that a fair critique of a fiction writer? Would the average person agree that you need to have lived in a place to write a fictionalized account of some of the stuff that goes on there, as long as you do sufficient research?

The essay contains many complaints that Latino writers are underpaid, their stories underappreciated, and so on. All of which may well be true! But that’s clearly a sign that something more than an issue with American Dirt qua American Dirt is going on here — other resentments are seeping into the critique.

Things get particularly odd when Bowles writes this:

People are stereotypes in this novel, participating in stereotypical activities (quinceañeras, for example). They live in a flattened pastiche version of Mexico, a dark hellhole of the sort Trump rails against, geographically and culturally indistinct. Lydia and Luca — despite having money — escape to the precious freedom of the US aboard La Bestia (that dangerous, crime-infested train) because of COURSE they do. But they don’t suffer the maiming, abuse, theft, and rape so common on that gang-controlled artery to the border.

This is an exceptionally weird and self-contradictory paragraph. In the first sentence, Bowles accuses Cummins of writing in a ‘stereotypical’ way by including a quinceañera. But… there are a lot of quinceañeras in Mexico! What is wrong with writing a novel in Mexico that includes a quinceañera? How is this even close to a fair criticism? This is like saying it’s offensive to portray Mexico City as a place with a lot of street tacos, when — and here I can speak from delicious fairly recent experience — Mexico City does, in fact, have a lot of street tacos.

But things get weirder still. In the second sentence, Bowles accuses Cummins of portraying Mexico as “a dark hellhole of the sort Trump rails against.” In the fourth, he gripes that the characters “don’t suffer the maiming, abuse, theft, and rape so common on that gang-controlled artery to the border.” So the accusation is that Cummins (1) presents Mexico as a dark and dangerous ‘hellhole,’ and (2) didn’t include enough rape and theft and abuse in her novel. Got it! That evil book of ‘trauma-porn’ didn’t include enough characters getting raped. This is clearly a good-faith critique.

I also got a chuckle out of Bowles’ accusation that the novel “does little to explore the complicity of the US in the violence wracking Mexico [emphasis his].” Let’s do the one-two thing again: In the same essay, Bowles accuses Cummins of (1) writing a book that portrays Mexico and Mexicans in an inauthentic light, and (2) not including enough scenes of the characters, as they are fleeing for their lives to the U.S., reflecting on the narcoeconomic and geopolitical nuances of their situation in the left-wing manner of, say — and here of course I’m just grasping at a random example — a “Mexican-American author and translator from deep South Texas… [who] teaches literature and Nahuatl at the University of Texas Río Grande Valley.”

If your goal, as a journalist, is to cover this controversy fairly, you should not link to and quote from an essay this silly and bad-faith. Instead, you should find intelligent, fair-minded people to comment on what Cummins got right and wrong, ideally by contacting experts who do not appear to be personally or professionally invested in the controversy but who can evaluate specific claims about the book’s purported shortcomings.

Similar deal a bit later in Jan-Lim’s article:

Cummins has also spoken candidly about her husband, who was undocumented, and the fear they both lived with regarding his immigration status. Her husband, however, is Irish, and some have said the reference to her husband as an undocumented immigrant is a dishonest portrayal meant to position herself more closely with the plight of Central American migrants.

“Some have said” is a warning light, a cousin of that bane of thoughtful writing, “could be seen as,” and a sign that some mind-reading could be afoot. In this case, the word ‘said’ points to a tweet by a guy named Geoff — 216 followers — which is part of a thread in which he opines:

Interview of Jeanine Cummins full of white lady vibes. A quote: “Luca & his mami happen to be Mexican, but they could be anyone. They could be Syrian or Rohingya or Haitian. They are human beings.” Being Mexican apparently not that important to the story. By asserting that there is some sort of “universal” migrant, Cummins equates her Irish husband overstaying his visa to the ppl in cages on the border who are fleeing real terror. That false equivalence is how she justifies the racist white-gaze mess that is #AmericanDirt. Mexican, Central American, Syrian, Rohingya not the same, & certainly not the same as conditions of a middle-class white guy from Ireland overstaying his visa. How offensive to equate his “tragedy” to theirs. How offensive to lump all brown people into one “faceless brown mass[.]”

This is really, really ridiculous. It’s ridiculous in a particularly annoying way, because I don’t want to waste time bashing some random dude’s bad opinions on Twitter, but the problem is BuzzFeed, a major news outlet, elevated that random dude’s bad opinions as evidence of the idea that Cummins did something wrong here.

So, briefly: Of course if Jeanine Cummins had said, of her main characters, “They could be anyone — they could be Mexican, or Irish, or Australian,” that would be a bit tone-deaf, at least without some further context. But she didn’t say anything like that. Rather, in making her point about dangerous migrations, she picked three groups — Syrians, Rohingya, and Haitains — which include massive numbers of people who are dealing with, or who have recently dealt with, horrific waves of violence and displacement and oppression. She is not saying anything remotely like “all migration stories are the same.” She is saying there is a general, universal story about fleeing hardship for a safer land, which of course is true.

And yes, Cummins has in the past pointed out that her Irish husband was undocumented, and that this caused them some stress. But that’s not the same as positing that being an undocumented Irish person of means is the same as being an impoverished Mexican migrant. No sane person would argue this, and anyone who attributes this view to Cummins should not be taken seriously on this subject ever again, unless and until they can point to where she made this actual argument. This Twitter guy also says it’s offensive of Cummins to “lump all brown people into one ‘faceless brown mass,’” a phrase which comes from a quote in which she is saying other people do that and she hopes her book can chip away at that tendency! If I say “Jews are often wrongly portrayed as money-grubbing and greedy,” and someone responds, “Oh, so you are saying Jews are money-grubbing and greedy?,” that person is a major asshole! He or she should be ignored, not cited in a major outlet’s coverage of a complicated controversy!

(Update: A reader writes in to highlight one point in her Author’s Note where Cummins does appear to introduce some unnecessary fuzziness:

I am a US citizen. Like many people in this country, I come from a family of mixed cultures and ethnicities. In 2005, I married an undocumented immigrant. We dated for gives years before we got married, and one reason for our prolonged courtship was that he wanted to get his green card before he proposed. My husband is one of the smarter, hardest-working, most principled people I've ever met. He's a college graduate who owns a successful business, pays taxes, and spends a fortune on health insurance. Yet, after years of trying, we found there was no legal route available for him to get his green card until we got married. All the years we were dating, we lived in fear that he could be deported at a moment's notice. Once, on Route 70 outside Baltimore, a policeman pulled us over for driving with a broken taillight. The minutes that followed while we waited for that officer to return to our vehicle were some of the most excrutiating of my life. We held hands in the dark front seat of the car. I thought I would lose him.

So you could say I have a dog in the fight.

It would have been the easiest thing in the world for Cummins to include the word ‘Irish’ somewhere in this excerpt so as to dispel any potential confusion about the situation. I can understand why people view this omission as a bit shady. Still, it’s not quite the same as her claiming her husband is in a strikingly similar, or the same, situation as a Mexican migrant without access to resources, which is the accusation that caught on online.)

Again: How much bad faith can you pack into a few tweets? How is any of this a remotely good-faith critique? Why would BuzzFeed elevate bullshit? Is the goal to illuminate the nuances of the controversy and explain it, or to amplify and stoke it?

***

Huffington Post’s article is even weirder. “‘American Dirt’ Isn’t Just Bad — Its Best Parts Are Cribbed From Latino Writers,” goes the headline of an article by David J. Schmidt, an author, podcaster, and translator. Like some of the other critiques of American Dirt, Schmidt’s contains certain elements that appear to be valid:

Cummins is not a person familiar with Mexico. She describes an imaginary country where people put sour cream on their street tacos, dress their chicken with BBQ sauce rather than mole, eat black licorice drops rather than mazapán, and fear the Bogeyman rather than El Coco. “American Dirt” is also riddled with linguistic gaffes, including a character thinking of her own mother as abuela (grandma). [emphasis his]

Well, “appear to be valid” at first glance, at least. Because I am a veteran of watching snippets of books get ripped out of context and misinterpreted during these blowups, I always attempt to double-check claims that can travel far and wide on the internet among people who haven’t read the book being dragged. In this case, I’m not sure the ‘barbecue’ claim is legitimate. According to Google Books, American Dirt contains zero mentions of ‘BBQ’ and just two of ‘barbecue.’ One is a reference to barbecue-style food that isn’t relevant, the other is from this sentence, which also contains the book’s only use of the word ‘sauce’: “In the shade of the backyard, there's the sweet odor of lime and sticky charred sauce, and Lydia knows she will never eat barbecue again.” But “sticky charred sauce” could be mole sauce! Cummins doesn’t appear to ever mention barbecue sauce itself. (I emailed Schmidt about this and will update the post if he responds, or if someone points me to something I missed. I could be wrong.)

(Update: Schmidt wrote me back. Here’s his note:

Hello Jesse,

Thanks for your email. Regarding your question:

The sauce is described as sticky, sweet sauce that is put on barbequed chicken. This is not a Mexican convention for grilling chicken.

It certainly could not be mole, as chicken is not grilled with mole sauce. Mole is poured onto boiled chicken, or the chicken boiled in the sauce.

Of course, this is just one of several atopisms throughout the novel, out of place cultural references as imagined by an outsider, but not anyone who knows Mexico.

Feel free to let me know if you have any other questions.

The plot, not entirely unlike certain sauces as they are being prepared, thickens further: I certainly didn’t see any mentions of a sticky, sweet sauce that is put on BBQ chicken in my Google Books perusal, including in the above quotes. I found out a Singal-Minded subscriber bought the book on Kindle, so I asked him to search for any such references as well. He, too, came up empty. Unless I’m missing something — again: still possible — Schmidt is referring to an excerpt from the book that doesn’t actually exist. If anyone can point me to information that changes my mind on this, I will, God help me, update this post yet again.)

Anway, most of Schmidt’s post centers not on questions of candies and sauces, but on the idea that, as the headline suggests, Cummins ‘cribbed’ the work of other authors. The dictionary definition of ‘crib’ is “copy (another person's work) illicitly or without acknowledgment.” It’s a serious charge, and Schmidt backs it up by pointing out that the book contains a scene of a boy getting run over by a garbage truck, which is also something that happens in Luis Alberto Urrea’s “By the Lake of Sleeping Children.” Other elements, from the train subplot, apparently bear resemblances to the work of “Sonia Nazario, whose 2006 narrative nonfiction book, ‘Enrique’s Journey,’ tells the story of a boy who migrates from Honduras to the United States atop the freight train known as La Bestia.” (I should be clear that ‘cribbed’ only appears in the headline, which Schmidt may not have written, but the implication of some sort of substantive wrongdoing is present throughout the article.)

The ‘accusation,’ then, is that a writer worked events ripped from real life into her novel. I don’t even know how to respond to that. It isn’t even an actual accusation, let alone one that warrants the explosive allegation of ‘cribbing.’

Making things even weirder:

I don’t believe any of Cummins’ writing meets the legal definition of plagiarism. She was clever enough to sufficiently reword and reframe these elements, and credits these authors as “inspiration” in her epilogue. However, several elements in her novel lean much more heavily on these preexisting works than on any original research. Indeed, Cummins appears to have never visited some of her locations at all.

Let’s update the ‘accusation’: a writer worked events ripped from real life into her novel, crediting the authors who produced those accounts rather than going to those places in real life and retracing their steps, or something. Oh no! I can see why people are pissed.

Schmidt accuses Cummins’ fictionalized account of tracking too closely to real life: “Cummins’ account of [garbage-truck victim] Ignacio’s burial in the dump, beneath a hand-painted cross, is suspiciously similar to the graveyard in the first chapter of Urrea’s book. It is baffling that Cummins would reproduce an entire story of real human tragedy, rather than simply making one up from scratch.” Sure, it’s baffling if you are unfamiliar with the concept of fiction writing and the research some novelists do to buttress their storytelling.

Let’s zoom out a bit: If any detail from Cummins’ fictional book doesn’t match real-life Mexico, that’s bad. If a detail matches real-life Mexico too closely, that’s also bad, because she is supposed to make up stories from scratch (at which point she’ll be accused of inauthentically rendered depictions of Mexico). Got it.

It’s almost like outrage is, itself, self-sustaining and often becomes detached from whatever kernel of truth may have initially spawned it, and that people can latch onto outrage and use it to elevate their profiles without being thoughtful or fair-minded.

(Update, 2/5/2020: A reader with a copy of American Dirt writes in to point out something pretty insane from Schmidt’s article.

Schmidt: “Cummins’ descriptions of a garbage dump in Tijuana and the border itself, as well as the trash truck scene, bear resemblance to passages in Urrea’s ‘By the Lake of Sleeping Children’ as well as ‘Across the Wire.’”

Cummins, in her book, writing about a kid named Beto from that dump: "Lydia knows a little about las colonias of Tijuana because she's read the books, because Luis Alberto Urrea is one of her favorite writers, and he's written about the dumps, about kids like Beto who live there."

So Cummins not only credits Urrea in her author’s note, but mentions him in the text itself as the reason a character knows about this specific garbage dump and the kids who live there. In light of this, how was Schmidt’s sentence published? It shouldn’t have been. This goes well beyond any reasonable disagreement over interpretation and right into outright distortion. That line should be edited or removed from the story and an editor’s note appended to the story explaining what happened.)

***

In other cases, the analysis some journalists are providing is so staggeringly bad-faith, and so disconnected from what any reasonable person arriving fresh at the scene of this controversy would consider a fair assessment of the evidence, that all you can do is wince and go for a walk or something.

Here’s Jezebel’s Shannon Melero, for example:

Cummins was inspired to write American Dirt in 2016 after listening to the discourse around immigration on the news; she has said the left’s narrative was “paternal” and obsessed with “saving these people” while the right made it seems as if a “wave of criminals” was “invading,” and shewanted to “humanize” the immigrants who were coming across the border. (At a pre-release event in November, tables were decorated with barbed wire, and Cummins received a barbed-wire manicure echoing her book cover.) It remains unclear what ultimately led her to believe that the people crossing the border needed to be rendered human, and to whom she purported to humanize them—particularly since there is already a large body of work about the topic of contemporary immigration, written by Latinx authors and amassed over decades. But the best way to “humanize” immigrants, she seemed to decide, was a monolithic description of their experience—which, she implied at her Barnes and Noble reading, can be divorced from race or location. “This story could be happening anywhere. This could be Australia,” she said to a room full of mostly white book lovers, as if immigrating from Australia is the same as immigrating from Mexico.

(Side-note, but it’s weird to me that all these progressive outlets are using ‘Latinx’ when a grand total of 2% of members of that group prefer that term — I thought the idea was to listen to members of minority groups? Maybe I misheard, or maybe there’s a pattern here.)

This is a bit whiplash-inducing. This sentence, in particular: “It remains unclear what ultimately led her to believe that the people crossing the border needed to be rendered human, and to whom she purported to humanize them—particularly since there is already a large body of work about the topic of contemporary immigration, written by Latinx authors and amassed over decades.” So now Jezebel, a progressive publication, is asking aloud whether we really should render human a migrant group endlessly demonized by the present occupant of the White House and his supporters — a group whose children are frequently ripped from their arms and detained indefinitely in squalid conditions — because… other people have already done that humanizing? They’ve been sufficiently humanized? Huh? As for the question of to whom they should be rendered human, perhaps the residents of the majority-white country that voted for the anti-immigrant president, some of whom have since helped propel the book up the Amazon bestseller list? This is almost entirely principleless writing — there is no underlying theory to the arguments other than Bad Lady Bad We Must Emphasize Her Badness.

Then there’s Melero’s interpretation of “This story could be happening… [in] Australia.” Her snarky, mind-reading reply: “as if immigrating from Australia is the same as immigrating from Mexico.” Melero probably doesn’t know this, but Australia has major issues of its own on this front, with immigration policies Amnesty called “unlike [those of] any other liberal democracy.”

So what’s a more likely, fair-minded interpretation of Cummins’ mention of Australia: that she’s pointing out migrants are forced to endure hardships in many different places, or that she thinks migrating from Australia is the same as migrating from Mexico? The answer is obvious. But again: the point of this style of outrage coverage appears not to be to critically engage with and evaluate the outrage, but to stoke it and, perhaps most importantly, broadcast oneself (that is, the journalist) as chiming in on the correct side of it, or at least giving that side as latitudinous a hearing as possible, even when many of that side’s arguments don’t pass the smell test. It’s rightside norms in action, basically.

***

I’d love to read a thorough account by a good-faith arbiter explaining exactly how outraged I should be about American Dirt! I just have no freaking clue where to find it. I am 100% positive that there is less there than the aforementioned outlets suggest, but, again, I also found the barbed-wire thing tacky and a bit exploitative, some of the Spanish stuff grating (not that I’m good at Spanish), and some other examples that seemed to have merit. But there were also multiple instances in which I had to do a lot of clicking and a lot of reading just to even fully understand the context of a given complaint that a major outlet presented as reasonable, only to realize that it wasn’t reasonable at all. And most readers aren’t going to do that! Most people aren’t obsessive weirdos who, on a given Tuesday morning, have enough of a gap in their writing schedule that they can afford to spend a couple bleary-eyed hours falling into an internet-hole. That’s why the net result of a lot of this coverage is going to be to mislead people, to nudge them toward perhaps being more outraged than they should be,

This is all tied to certain big problems going on in journalism right now. It’s depressing.

Questions? Comments? Accusations that the blog post format is, itself, appropriative and exploitative, and I’ll see exactly what I mean if I watch the 200-minute YouTube video you just posted? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal, though I’m taking a hiatus from the latter because there’s just too much trauma-porn on there.

Thanks, Jesse, for taking a look at this. From my perspective of a writer, I was so irritated by all this that I promptly bought "American Dirt" for my Kindle, so I could read it myself (though I haven't, yet).

Re these lines from your piece, "If any detail from Cummins’ fictional book doesn’t match real-life Mexico, that’s bad. If a detail matches real-life Mexico too closely, that’s also bad, because she is supposed to make up stories from scratch (at which point she’ll be accused of inauthentically rendered depictions of Mexico)."

This, it seems to me, is the "gotcha," the ludicrous Catch-22 of almost all "cultural appropriation" (and related) kerfuffles I've read about. In the YA fiction hubbub, writers seem to be attacked for either a) having the temerity to include characters who do not share their various identities or background or b) writing only about people like themselves and therefore "erasing" all others. There is literally no way to win.

As I say, I haven't read "American Dirt." But only recently has it become a fad to assume that writers (or filmmakers, musicians, any artist) should "stay in their lane" and refrain from writing about anyone who doesn't precisely mirror their own background. Taken to its logical extreme, no artist should ever create art that is not, fundamentally, of, by and about themselves — a world of solipsistic, masturbatory art. Let's "cancel" Shakespeare, Faulkner, hell, any writer of color who has ever written about a white character, and on, and on.

Incidentally, searching "American Dirt" on my Kindle, I see 69 references to "abuela," virtually all from the viewpoint of Luca, who is referring to his grandmother. I don't actually find one where Lydia, his mother, refers to "abuela." But if she does, that would not be in the least bit surprising. My sister refers to "Grammy" when speaking of our mother to her sons, after all.

While you didn't bring this up, I also want to push back against the idiotic notion that there is a codified, approved, correct version of People X's experience. I notice that Salma Hayek, born and raised in Mexico, was bullied into questioning her previous endorsement of Cummins' book. But isn't that, in itself, "erasing" someone's "live" experience? To Hayek, the novel was authentic enough that she praised it — why does some random critic get to trash her because her understanding of her own Mexican-ness led her to appreciate the novel?

I am, like you, a liberal. But man, as a writer and a skeptic, it's really distressing to witness the lunacy that some on the "woke left" and idiot Twitterati are trying to force-feed us these days.

Kat Rosenfield had a good article about this on Arc Digital. According to her, the main issue appears to be that the publishing company hyped the book to such enormous degrees (the 7-figure sum, the comparisons to Grapes of Wrath) as an Important Seminal Novel that they were practicality begging for a Twitter Backlash.

One thing I've noticed about all the Outraged pieces, whether they're about a book, a movie, a tv show, or a videogame, is that every single one of them inevitably invoke Trump. When he won in 2016, it's like a moral panic was unleashed among culture writers. Suddenly all art must be Capital-W Woke or else it risks empowering him and his supporters. Meanwhile, all this outrage only increases the book/movie's popularity (see also Joker).

Bottom line: Trump will win again if all this stuff persists. People really, really don't like being scolded all the time for enjoying things.