Liberal Condescension And Statistical Dishonesty Won't Help Crime Victims

On an extremely silly and misleading article in Gizmodo and The Markup

Once in a while an article comes along that so nicely sums up so many of my frustrations with media coverage of difficult issues that all I can do is sigh. Sigh, and write about it here.

That happened last week. The article was published by Gizmodo and The Markup, and it has the headline “Crime Prediction Software Promised to Be Free of Biases. New Data Shows It Perpetuates Them.” There is a lot to unpack in it, but mostly I’m just surprised that the authors — and, apparently, a lot of people enthusiastically circulating it online — believe that it says much of anything at all. I also think it neatly reveals some increasingly common shortcomings in how liberal journalists think through race, crime, and policing, as well as the questions of what racial disparities mean and how we should respond to them. A certain head-in-the-sand paternalism has set in that isn’t really going to help, and that treats residents of dangerous neighborhoods more like helpless pawns being swatted around by white supremacy than fully fleshed-out humans with their own preferences and politics and agency.

Let me get a little bit of throat-clearing out of the way: I don’t know much about predictive policing. I don’t know whether PredPol, the software being criticized here, works, and I think that, generally speaking, law enforcement is a site of a lot of grifting, which is probably a result of 1) big budgets, in some cases; and 2) crime being a genuinely difficult societal problem that eludes easy solutions. My book has a chapter about the mid-1990s pseudo-psychological theory of the “superpredator” — a theory that was, in retrospect, very silly, and probably caused a lot of harm by casting juvenile offenders involved in (usually) drug-related violence as amoral killing machines, rather than kids living in very difficult circumstances, in neighborhoods often flooded by crack and guns. (“ ‘Superpredators’ Arrive: Should we cage the new breed of vicious kids?” went an infamous Newsweek headline.)

Poke around in this space and you’ll find that there has been lots of other grift-y stuff over the years, from lie-detector tests (which don’t work) to supposed body language and graphology experts who sometimes make big money selling their wares to credulous prosecutors and police departments who don’t know how to ask for quality evidence (which isn’t on offer). Even the very hard-science-seeming parts of law enforcement, like forensics, often turn out to be held together with Scotch tape and rubber bands. This is all very bad, and in the worst cases leads to wrongful convictions (or acquittals!), wasted time and money, and so on.

So you, a characteristically reasonable reader of this very evidence-based newsletter, might be asking, How can you critique this article when you don’t know much about predictive policing? Easy: the journalists themselves made no effort to evaluate the software’s effectiveness, either. The software’s effectiveness is actually beside the point.

If You Don’t Ask An Inconvenient Question, You Won’t Get An Inconvenient Answer

PredPol’s marketing language explains that it “uses a machine-learning algorithm to calculate predictions” about crime, and that it employs three types of data, “crime type, crime location and crime date/time,” to do so. So the algorithm basically tells law enforcement, “I think there is gonna be this type of crime at this location at this time.” And according to Gizmodo and The Markup (I’m lazy so I’m just going to mention Gizmodo, the larger and more well-known site, from now on), some police departments use this input to help determine where police should patrol when they’re not actively responding to a call.

Gizmodo’s argument is that because PredPol seems to predict more crimes in blacker and poorer neighborhoods than in whiter and richer ones, it “perpetuates” bias, as per the article’s headline:

Residents of neighborhoods where PredPol suggested few patrols tended to be Whiter and more middle- to upper-income. Many of these areas went years without a single crime prediction. By contrast, neighborhoods the software targeted for increased patrols were more likely to be home to Blacks, Latinos, and families that would qualify for the federal free and reduced lunch program. These communities weren’t just targeted more—in some cases they were targeted relentlessly. Crimes were predicted every day, sometimes multiple times a day, sometimes in multiple locations in the same neighborhood: thousands upon thousands of crime predictions over years. A few neighborhoods in our data were the subject of more than 11,000 predictions. The software often recommended daily patrols in and around public and subsidized housing, targeting the poorest of the poor. [throughout this piece I’ll be compressing excerpts that span multiple short paragraphs into one bigger one.]

As soon as I read this, I found my common sense alarm ringing loudly. This is anecdotal, but I’ve lived in places with almost no crime (my hometown), places with a lot of crime (Columbia Heights, D.C., where I saw a kid shoot into a group of apparent rivals [he luckily didn’t hit anyone], my housemates and I regularly heard other gunshots, I got mugged and had my car broken into, and just about everyone I knew in the area had similar experiences, including a friend who randomly got punched in the face by teenagers), and places that are fairly safe but definitely not crime-free (present spot in Brooklyn, where genuinely menacing stuff has been rare enough that this stood out as quite jarring). It doesn’t strike me as weird at all that an algorithm seeking to predict crime might predict many crimes in some neighborhoods and none in others, because that roughly maps onto my own experience.

So right off the bat, an obvious question should pop into the skeptical reader’s mind: is this algorithm simply reproducing preexisting crime differentials? There is more crime in poorer neighborhoods than richer ones, to oversimplify slightly, and richer neighborhoods are disproportionately whiter ones. An algorithm could definitely predict crime in a biased-seeming way that also happened to be accurate. And as a reader, you should always, always, always be skeptical, regardless of the subject, when you are presented with numbers devoid of context. You should ask questions like, “11,000 predictions of what sorts of crimes over how long a period?” Surely there are some places where 11,000 crimes occur, in real life, over some period of time. In the absence of any context, it feels like the authors are simply trying to throw out a big number that will make readers think something is wrong with this aspect of the algorithm. But is something wrong with this aspect of the algorithm? I’d argue that the mere fact that some areas are predicted as having much more crime than others offers effectively no evidence to support that idea. In fact, I’d certainly trust an algorithm making those sorts of predictions over one that predicted effectively equal levels of crime everywhere.

Most of this section of my critique is going to be about the fact that black people are victimized by crime much more than white ones. This should not be a controversial claim. “Stark racial disparities in murder victimization persist, even as overall murder rate declines,” goes the title of a 2018 blog post published by that famously reactionary organization, the Prison Policy Institute (“HELP US END MASS INCARCERATION”). The first half of the sentence could have been written at basically any point in recent American history, and the same goes for a lot of other sorts of serious crimes. PredPol’s algorithm is based on reported crimes, so our default assumption should be that any such algorithm should predict more crimes in areas that. . . have had more crime in the past. And those neighborhoods will be blacker and poorer, on average, because black people are victimized more frequently by crime than white ones, especially in poorer neighborhoods.1

So it could be that PredPol is doing its job well, and as a result generating “biased” results. One obvious solution would be simply to check whether PredPol is reasonably effective at actually predicting where there will be crime. I kept thinking I would get to that part of the Gizmodo article. I read and I read. I read, and children were born and grew up and had kids and grandkids of their own, and still I read, waiting for this information. Finally, almost four thousand words in, or this far down in the article. . .

. . . I got to a sentence reading: “We did not try to determine how accurately PredPol predicted crime patterns.”

Oh. So they didn’t check? This is weird given how ambitious an effort this was and how many other statistical comparisons the authors — there were seven of them — were able to make. And if there were some feature of the data that would render such a comparison impossible, surely they would say so? But they don’t say so. They chose not to check something that could have largely undercut the premise of their article.

They did address the possibility that PredPol is simply echoing preexisting patterns, but in a very weird and rather misleading way: by kinda-sorta denying there even are meaningful crime differences between neighborhoods. I say “kinda-sorta” because 1) it’s hard to figure out exactly what they’re claiming, 2) I don’t think they explicitly say this anywhere, and 3) because it seems almost impossible they could actually be arguing what they seem to be arguing. This was one of the more head-scratching sections of the article. At the very least, the authors are creeping right up to the line of saying that there aren’t meaningful neighborhood-level differences in crime rates, which is insane.

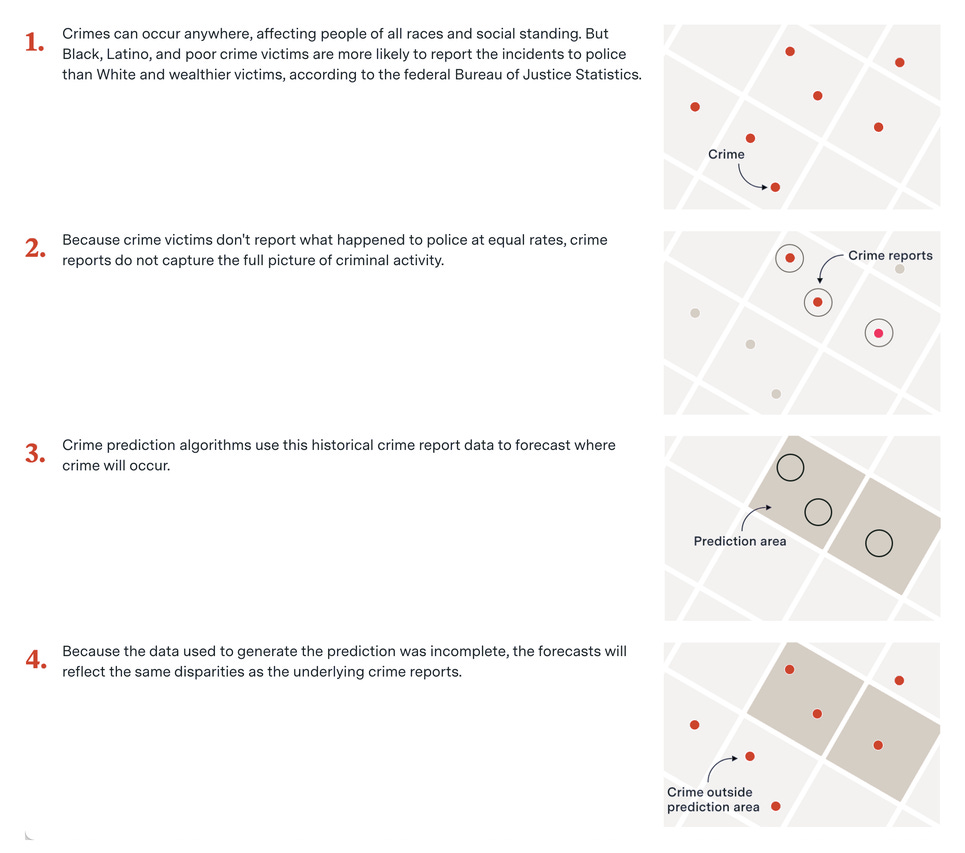

First, there’s this chart, which gives what seems to be a complete account of Gizmodo’s gripe with this style of predictive policing:

“Crimes can occur anywhere, affecting people of all races and social standing.” This is a non-sentence. It doesn’t say anything that anyone doesn’t already know. Of course crime can occur anywhere. That’s not really the issue here — the issue here is which areas have more crime than others. And you’ll notice that completely absent from this chart is any mention of actual, real-life discrepancies in crime rates that aren’t mere statistical artifacts. In this view, it’s solely between-group reporting discrepancies, rather than actual crime differentials, driving the algorithm’s perception that different areas are at different risk of crime.

This should come across as a very strange point if you’re familiar with the actual magnitude of the difference between safer and less safe neighborhoods in America, and yet the authors really go all-in on it:

In his email to The Markup and Gizmodo, [PredPol CEO Brian MacDonald] said the company’s choice of input data ensures the software's predictions are unbiased. “We use crime data as reported to the police by the victims themselves,” he said. “If your house is burglarized or your car stolen, you are likely to file a police report.” But that’s not always true, according to the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). The agency found that only 40 percent of violent crimes and less than a third of property crimes were reported to police in 2020, which is in line with prior years. The agency has found repeatedly that White crime victims are less likely to report violent crime to police than Black or Hispanic victims. In a special report looking at five years of data, BJS found an income pattern as well. People earning $50,000 or more a year reported crimes to the police 12 percent less often than those earning $25,000 a year or less.

The BJS report is very sociologically interesting, and indeed finds some gaps. But let’s put them in context. Here are the percentage of white, black, and Hispanic victims of violent crimes who did not report their crimes to the police during the 2006 to 2010 span analyzed:

White: 54%

Black: 46%

Hispanic: 51%

Let’s stick to the black-white dyad, which is in many senses the most important one (there’s also not much of a gap between white and Hispanic non-reporting). According to this, whites are about 17% more likely (54 / 46 = 1.17139) not to report to police a violent crime they have been victimized by. (Correction: As originally published, the bolded 1 was missing. I am not good at math but I promise I am aware that a larger number over a smaller number equals more than one.)

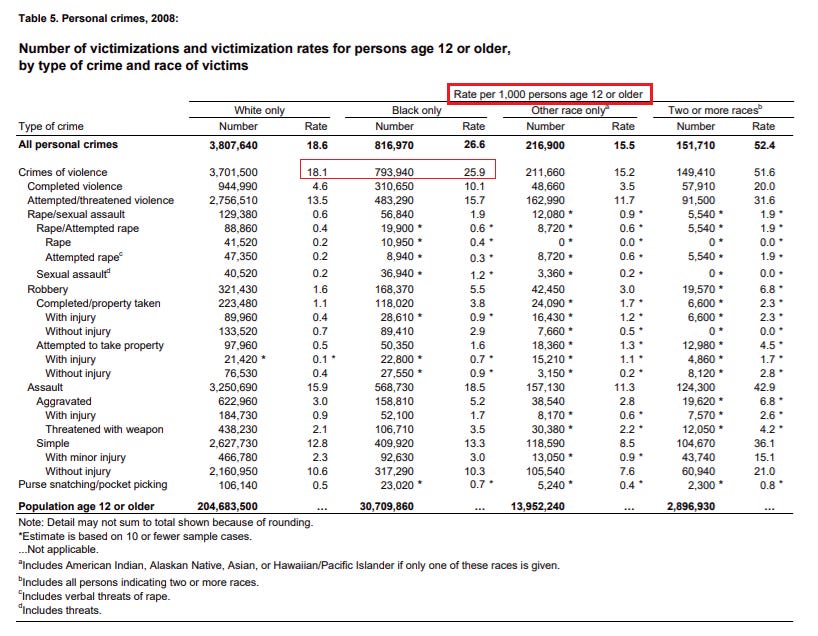

How does this gap compare to how many crimes whites versus blacks are victimized by, according to the records? Here’s a 2008 table reporting the crime victimization rates for whites versus blacks from the BJS’s report on crime that year:

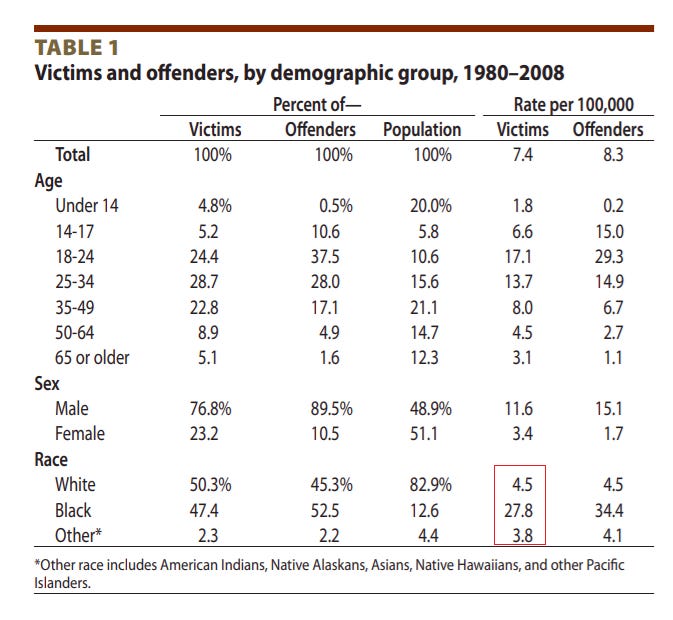

So in 2008, black people were more than twice as likely as white ones to be the victims of “completed” violent crimes. And since this document is based on victims’ own reports, it doesn’t include murder. For murder, the gap is not just bigger — it’s genuinely horrific. From 1980 to 2008, according to another BJS report, black people were more than six times as likely to be murdered, on a per-100,000 basis, than white ones.

Now, I’m using these slightly older numbers to compare them to those in the report Gizmodo is citing. Violent crime has gone down a huge amount since 1980 overall, and the benefits have flowed disproportionately to black people (black males, more precisely), since they were victimized the most. This study says that between 2000 and 2019, the ratio of black homicide victims to white homicide victims was 5.6:1, which would represent a dip from the 1980 to 2008 numbers, but is still a horrific difference (there was also a reversal of progress from 2013 to 2019, according to the authors, with the black victimization rate ticking back up).

However you slice it, and whichever recent data you use, the point is that these disparities absolutely, totally dwarf the reporting-rate gaps Gizmodo is leaning on to argue that PredPol’s data is too noisy to be useful.

Let’s lay this out directly, using some of the above numbers:

—After being victimized by a violent crime, a white person is about 17% less likely to report it to police than is a black person

—Black people are about 120% more likely to be the victim of a completed violent crime than white people (10.1 vs. 4.6 per 100,000, as per above table)

—Black people are about 460% more likely to be murdered than white people (5.6x differential, as per above)

I’m being slightly fuzzy here, mixing together different stats from different time periods, but the point stands: that gap in reporting is interesting and worthy of study in its own right, but it represents only the tiniest nibble of the stark disparities we’re discussing here — disparities that, we should remember as we gaze at gentle, sterile numbers, represent real-life people getting assaulted and raped and killed.

I don’t know anyone, firsthand, who has been murdered — thankfully. Most of my friends and family members, who are generally also from privileged backgrounds, also don’t know anyone who has been murdered. In other sorts of neighborhoods, many residents know multiple people who have been murdered. We can’t understate the importance of this difference. It’s almost insulting to pretend that discrepancies in reporting are particularly important when it comes to discussing the most violent crimes (which are the crimes cops are, or at least should be, most interested in preventing and solving).

Of course, the Gizmodo article doesn’t provide any of this context. There’s no attempt to stand the magnitude of the reporting discrepancies next to the magnitude of the victimization discrepancies. By dint of the decisions the authors and editors made, readers are going to come away extremely misinformed about what the data actually show:

This disparity in crime reporting would naturally be reflected in predictions. “There’s no such thing as crime data,” said Phillip Goff, co-founder of the nonprofit Center for Policing Equity, which focuses on bias in policing. “There is only reported crime data. And the difference between the two is huge.”

This is the only time he is quoted in the piece, and that quote is likely drawn from a broader context. But it’s basically impossible that Goff, a well-known name in this area, genuinely thinks there’s “no such thing as crime data” in the sense that a 5.6x differential between the black and white murder victimization rates has no real-world basis or policing ramifications — or that it, and other similarly large and well-established discrepancies, wouldn’t show up in predictive data.

What I’m saying is that this is an exceptionally strange and misleading statistical claim.

Liberal Journalists Who Write About Policing Should Stop Being So Paternalistic To Black And Latino Americans

There’s some other weirdness in this Gizmodo article that jumped out at me: throughout the article, the authors treat police patrols as inherently bad in a manner that is deeply paternalistic and at odds with the on-the-ground reality and preferences of perhaps tens of millions of black and Latino residents of lower-income, higher-crime areas.

Now, I shouldn’t even need to say this, but of course there are many, many instances of harmful over-policing in the United States, particularly in low-income black communities. For one of countless examples, see this piece by Matt Yglesias, who is well-studied on the subject of crime and who has no patience for faddish, knee-jerk responses to it on either side, on just how bad “Stop and Frisk” was.

But there’s a big difference between saying certain police practices are abusive and treating the mere presence of police as inherently bad. That’s what this Gizmodo article does with its language about how “These communities weren’t just targeted more—in some cases they were targeted relentlessly.” Setting aside the fact that the authors admit that “It’s impossible for us to know with certainty whether officers spent their free time in prediction areas, as PredPol recommends, and whether this led to any particular stop, arrest, or use of force,” the choice of language is striking. “Targeted” suggests that it is harmful to a neighborhood’s residents for police to patrol it, and throughout the article the only community voices highlighted are those who agree with this sentiment. Over and over and over, Gizmodo quotes local activists who don’t want police in their neighborhoods and/or who are alarmed at the prospect of more frequent patrols.

For example:

In Birmingham, Alabama, where about half the residents are Black, the areas with the fewest crime predictions are overwhelmingly White. The neighborhoods with the most have about double the city’s average Latino population. “This higher density of police presence,” Birmingham-based anti-hunger advocate Celida Soto Garcia said, “reopens generational trauma and contributes to how these communities are hurting.”

(Late-addition paragraph: Before getting to my actual point here, I just need to point out how strange this whole bit is when you look at Birmingham’s racial demographics. First of all, it isn’t the case that “about half the residents [of Birmingham] are black.” According to the Census’s own data, that number is almost exactly 70%. That’s a very easy thing to get right and a strange thing to get wrong. Left out of this paragraph is that Birmingham also has very few Latinos: The U.S. population is about 18% Hispanic, while in Birmingham that number is around 4%. So the neighborhoods with the most crime predictions are about 8% Hispanic, in a city that’s 70% black. I can’t even figure out how this is supposed to be a particularly alarming outcome, given that that’s still such a small percentage of that neighborhood’s population. This has a whiff of a statistical fishing expedition, and the absence of hard numbers and denominators in an article so dependent on statistics should, again, always raise the eyebrow of critical-minded readers.)

In this view, the mere presence of more cops “reopens generational trauma.” I can definitely understand why, for the many people who have had bad experiences with the police, they might not always be welcome. But the problem is that Gizmodo is doing some serious cherry-picking to present readers with a very inaccurate gloss of black and Latino opinion on this subject.

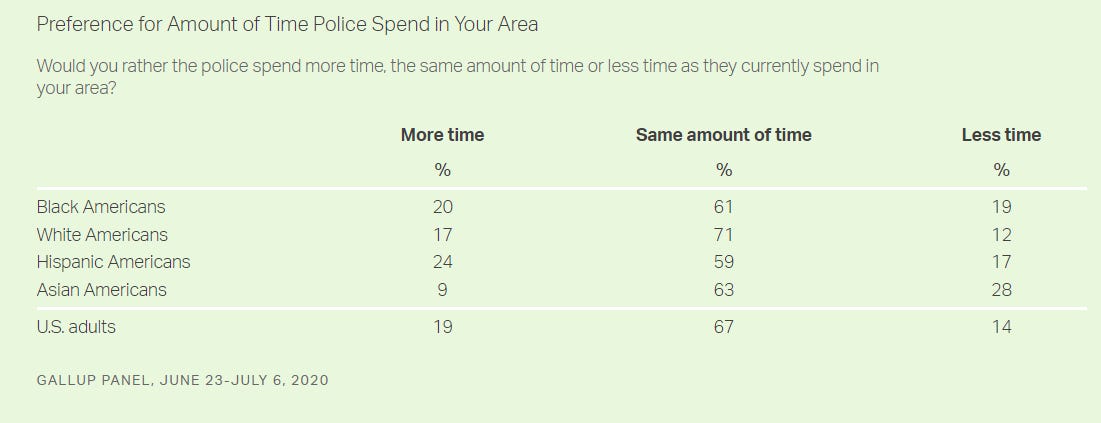

Polling consistently shows that the overwhelming majority of black and Latino people do not want the police presence in their neighborhoods reduced. Take this result from Gallup polling conducted about a month after George Floyd’s killing (the article has an early-August 2020 dateline but the data were collected earlier), at what was likely the peak of the backlash against law enforcement we saw in some quarters. Respondents were asked “Would you rather the police spend more time, the same amount of time or less time as they currently spend in your area?”

As you can see, black Americans were about evenly split between the “More time” and “Less time” categories, with a majority thinking the police presence in their neighborhood was already at the right level. Hispanic Americans were a bit more in favor of a heightened police presence. If you combine “more time” and “same amount of time,” you get huge majorities — 81% for black Americans and 83% for Hispanic ones. There’s always some degree of tea-leaves-reading involved in interpreting polls, but the point is that it is impossible to look at the numbers we have and conclude that Celida Soto Garcia’s view is anything but uncommon among black and Latino people. (I’m going to use Latino and Hispanic a bit interchangeably, since I’m realizing that even though I usually favor the former, the latter is frequently used in the polling and other data I’m citing.)

None of this is to say black and Hispanic Americans are ardently pro-cop or don’t, by some measures, report high rates of harassment at cops’ hands. Rather, there is a consistent sentiment expressed at the level of averages, especially among black Americans, that goes something like, You’re not there when we need you to protect us, and then when you do show up you all too often harass us. It is a much more nuanced position than I am traumatized by the presence of cops and don’t want them to patrol my neighborhood. I will recommend the same two books I recommend whenever this subject comes up, because they’re both essential: Black Silent Majority: The Rockefeller Drug Laws and the Politics of Punishment by Michael Javen Fortner and Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America by James Forman, Jr.

Lest I be accused of doing my own cherry-picking here, let’s look at another, more recent survey, “Results from the Policing in America Survey by Race and Ethnicity in Cook County, Illinois, and Dallas County, Texas.” These results are from a representative survey of respondents in these communities’ attitudes toward policing, and the data were collected in February and March of 2021, so this is all more recent.

In Dallas:

When asked about the police presence in their neighborhood, 43.4% of residents believed there was the right amount of police presence and 38.2% believed there was too little. Resident perceptions of the extent of police presence in their neighborhood did not vary by the race and ethnicity of the individual.

In Cook County:

When asked about the police presence in their neighborhood, 43.2% of residents believed there was the right amount of police presence and 35.5% believed there was too little. Compared to white residents, Black and Hispanic residents were more likely to report too few police officers in their neighborhoods: white 26.4% vs. Black 46.0% (P≤.001), and vs. Hispanic 48.6% (P≤.05).

It’s the same basic pattern: in both of these areas, which are very diverse and which have some high-crime neighborhoods, overwhelming majorities of residents are opposed to any reduction of police presence, and sizable minorities want more cops. In Dallas there were no racial differences in these sentiments, and in Cook County black and Hispanic residents were more “pro-cop,” in this sense, than white ones. (This is just speculation, but Cook County includes Chicago, which has notorious levels of segregation and attendant crime discrepancies. “West Garfield Park, the city’s most dangerous community area, has seen a rate of shootings nearly 20 times higher than downtown,” reported the Sun-Times in October 2021. “The gap is even higher with six other police districts on the North Side.” So I don’t think we should be surprised that black and Hispanic people there are much more concerned about inadequate levels of cops in their neighborhoods than are white ones.)

Statistically speaking, it should be very hard to do what Gizmodo did in this article — to only find black and Latino voices quite opposed to having their neighborhoods be patrolled by police. But that’s the preferred narrative. I think that certain journalists and editors who either have very radical-chic views on policing themselves, and/or who have never looked at the polling, and/or whose contact with black and Latino people is mostly limited to progressive activists and academics and journalists within their social and professional circles, seek out and elevate a very narrow subset of minority voices precisely because these voices are ardently skeptical of police in a way the average black or Latino American — like the average American of any racial group — just isn’t.

Longtime readers of this newsletter might recognize this pattern. Something similar happened in a front-page article about police defunding the New York Times published in June of 2020. As I wrote at the time, despite the fact that more than a dozen Times staffers worked on this article (three coauthors, nine contributors, plus however many editors), no one thought to include any mention of actual black and Latino opinion on police defunding. If they did, it would have complicated the article a little, because black and Latino people are rather opposed to large-scale police defunding. As is always the case with survey questions, you get wildly different answers when you tweak the question. You will find solid support for demilitarizing the police and trimming certain other excesses of how they do their jobs, but whenever you return to that most specific, most-relevant-to-everyday-life question — Do you want more or fewer cops in your area? — you get the same answer: actual, widespread defunding, let alone abolition, is deep underwater among the groups it is supposed to benefit the most.

But again: it’s certain voices only that get elevated, and that likely leads to consumers of mainstream outlets developing very skewed understandings of what black and Latino Americans want in policing, which probably reinforces the probability of white editors and writers having a tougher and tougher time keeping the concepts “the inclusion of black voices” and “the inclusion of voices that are very skeptical of having cops around” separate.

A Final Note On Disparity Allergies

There’s what feels like a growing sentiment in some liberal academic and journalistic circles that racial disparities are either made-up or proof that the thing that generated the discrepancy is itself racist, and that the conversation needs to end there, without any deeper or more nuanced analysis.

So we need to banish the SAT, for example, because white kids get higher scores than black ones, and the California public university system has gone ahead and done just that. But as I’ve argued, this view can lead us astray. Responding to racial discrepancies in the SAT by banning it might cause us to embrace admissions practices that are more susceptible to bias. And as Freddie deBoer just argued, “Racial Disparities in the SATs Are Exactly What Antiracists Should Predict.”

That is:

The average Black student really does struggle more with reading and algebra etc. than the average white student, and the average rich student really does perform better than the average poor student. Again, this is absolutely what you’d expect if you have a progressive outlook on structural disadvantage. But we can’t get anywhere if we pretend that these gaps are the product of measurement error, nor by positing an immense conspiracy among millions of teachers and administrators to pretend that Black and poor students are struggling when they aren’t. In the long run, such denialism hurts precisely the students it ostensibly helps, as it does nothing to fill in the gaps of human capital under which they suffer. I have very few good things to say about old guard education reform types, but they have always been willing to look at such gaps and understand that the gaps themselves, the underlying lack of ability, are the core problem, the core injustice. Disadvantaged students struggling to get into college is a symptom, not the disease. And the SAT[s] are merely a thermometer that diagnoses that disease.

This Gizmodo article is making the exact same mistake. It’s assuming that because data show racial discrepancies in crime levels, the process producing that data must be biased, and that we should probably toss the algorithm. But to borrow from deBoer, disadvantaged neighborhoods struggling with high levels of crime is a symptom, not the disease. And crime statistics are merely a thermometer that diagnoses that disease.

The common problem with jumping to “a racist process produced these statistical discrepancies” in all these instances is that you are likely to miss the actual sources of the discrepancies you’re seeing, which are fairly deeply rooted. That’s definitely true of this crime data: it’s a cop-out to say “Well, this algorithm is biased, so we should trash it,” at least without first checking whether it’s accurate. Because an accurate crime-prediction algorithm would predict more crime in poorer and blacker neighborhoods. That’s because one of the terrible ways poor and black people suffer, relative to richer and white ones, on average, is that they live in more dangerous neighborhoods. You are not really addressing their concerns, their lived experiences, by wishing these problems away. It isn’t kind or thoughtful or an act of allyship to pretend that these horrific differentials in who is shot dead on the street don’t exist and don’t scream out to be addressed, whether or not software like PredPol is the right approach.

This is a head-in-the-sand approach to racial justice, and it’s increasingly common. It feels like it’s more about making a certain type of liberal feel righteous and good about their worldview — Boo police! Boo racist algorithms! — than listening to the people who need help the most, let alone actually helping them.

Questions? Comments? Predictive algorithms that can tell me when I’m likely to publish a bad newsletter without bias? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com. Check out my new thing on Callin. You need Apple to download the app for now (that’s changing soon), but that link will let you listen to all the episodes I’ve already recorded in your browser. And it’s all free.

Image info: US attorney general Merrick Garland (C) holds a listening session on reducing gun violence at St. Agatha Catholic Church in Chicago, Illinois, on July 22, 2021. — Garland and the deputy U.S. attorney general today announced an initiative to reduce gun violence with five cross-jurisdictional strike forces by disrupting illegal firearms trafficking in key regions across the United States. (Photo by Samuel Corum / POOL / AFP) (Photo by SAMUEL CORUM/POOL/AFP via Getty Images).

Whenever you mention this, people will pop up to point out that on average, black people in the United States commit more crimes than white ones. For obvious historical reasons, this is an incredibly fraught subject, and I think we are locked in a bit of a toxic cycle where conservatives tend to keep pointing this out, sometimes in places where it isn’t really relevant or without important context, and liberals tend to pretend that this claim isn’t statistically true. It isn’t relevant to this article, which is only about victimization, but if I didn’t include this footnote I’d be accused of somehow trying to hide or paper over something, so here we are, down here in the footnotes, the metaphorical dusty basement of a Substack post.

I devoted a short passage of the Superpredator chapter of my book, which is mostly about crime sensationalization and the turn toward some truly excessive “tough on crime” policies in the U.S. in the 1990s, to the racial crime gap. Here’s part of it, with footnotes swapped out for links: “There’s significant evidence that when certain variables are controlled for, the black-white crime gap closes dramatically. One article by a pair of sociologists, for example, looked at trends in rates of violence among whites, blacks, and Latinos since 1990 and found that “consistent with expectations, structural disadvantage is one of the strongest predictors of levels and changes in racial/ethnic violence disparities.” Because blacks face so much more structural disadvantage than whites by any conceivable measure, the crime gap is no surprise. The economist Dionissi Aliprantis takes a different tack, finding that “Conditional on reported exposure to violence, black and white young males are equally likely to engage in violent behavior” [emphasis mine].

I think it’s pretty straightforward to say that, all else being equal, groups trapped in intergenerational cycles of poverty are more susceptible both to being victimized by and committing crimes. This is the subject of a lot of feverish and often plain racist speculation, but based on the evidence we have, I think it’s pretty clear that these sorts of crime differentials can be explained rather comprehensively by such variables. I also think that race is such a blunt instrument here, and that there’s likely an important difference, in terms of which risk factors you’re exposed to, between being an American descendant of slavery and being a more recent immigrant from Africa or the Caribbean (evidence suggests that some of these “black” subgroups are doing quite well, socioeconomically, and generally speaking those who are well-off socioeconomically enjoy better outcomes with regard to both crime victimization and perpetration). Just like there are some communities of white people with much higher crime rates than others.

Anyway, that’s all I want or need to say about this here. It’s silly to ignore this gap but it’s also silly to strip it from context and to suggest that it, on its own, proves much of anything other than that there are massive disparities in the experiences of different Americans. I think more and better data on different subgroups would actually be helpful here and would take some wind out of the sails of the idea that the black-white crime gap is some sort of Forbidden Truth liberals are terrified of and trying to hide.