If You Can’t See That Adam Rubenstein Was Treated Unfairly, You’re Being A Jerk

It’s time for my quarterly navel-gazing media kvetch-session

The other day The Atlantic published an article by Adam Rubenstein, a young conservative editor who was wrongly blamed for the supposed flaws in the Tom Cotton op-ed that caused an implosion at The New York Times, leading to his departure, James Bennet’s departure, and the reassignment of Bennet’s deputy, James Dao, to a different section.

There’s no need to revisit all the specifics. Just read Rubenstein’s piece. It is the same story Bennet himself told recently, but from a different angle, and equally worth reading (that is, very). It paints a picture of a fairly dysfunctional institution that, during the worst excesses of the reckoning, chewed up and spit out its own rather than stand up for its stated principles. The most galling stuff, in both stories, centers on the way the Times spread misinformation about its own staffers via its own reporting on the incident. Rubenstein and Bennet were both victimized by extremely slipshod journalism that made them and their editorial decisions look far worse than they actually were — reporting that, had it originated with Breitbart rather than the Times itself, would have been the target of consensus denunciation on the part of mainstream journalists.

Anyway, I don’t want to focus on the Cotton op-ed; rather, I want to focus on sandwiches.

Rubenstein’s story begins thusly:

On one of my first days at The New York Times, I went to an orientation with more than a dozen other new hires. We had to do an icebreaker: Pick a Starburst out of a jar and then answer a question. My Starburst was pink, I believe, and so I had to answer the pink prompt, which had me respond with my favorite sandwich. Russ & Daughters’ Super Heebster came to mind, but I figured mentioning a $19 sandwich wasn’t a great way to win new friends. So I blurted out, “The spicy chicken sandwich from Chick-fil-A,” and considered the ice broken.

The HR representative leading the orientation chided me: “We don’t do that here. They hate gay people.” People started snapping their fingers in acclamation. I hadn’t been thinking about the fact that Chick-fil-A was transgressive in liberal circles for its chairman’s opposition to gay marriage. “Not the politics, the chicken,” I quickly said, but it was too late. I sat down, ashamed.

It’s the sort of colorful lead anecdote that magazine editors dream about. Just complete insanity. But of course the article wasn’t really about this one dumb chicken incident — in fact, Rubenstein proceeds to explain, in careful, dispassionate detail, how his career was permanently disrupted by a moral panic and the sloppy and inexcusable behavior of his own colleagues.

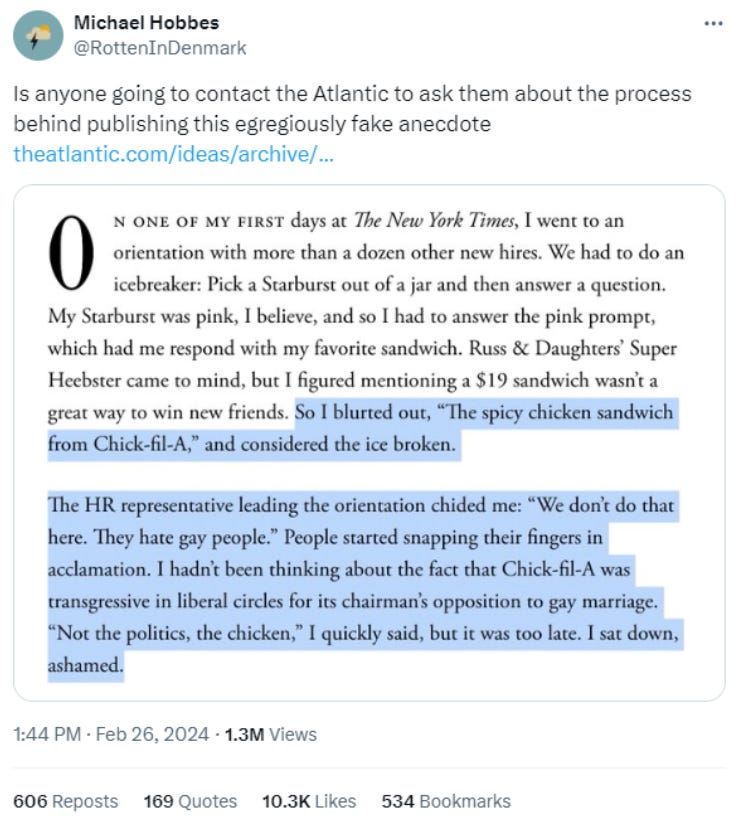

So naturally, a bunch of journalists instantly claimed that Rubenstein was lying — of course this chicken event never happened. Michael Hobbes, who makes a very good living as a professional debunker despite having an accuracy batting average about equal to what my batting average would be in an actual Major League Baseball game, thundered: “Is anyone going to contact the Atlantic to ask them about the process behind publishing this egregiously fake anecdote[?]”

Perhaps the most famous journalist to express this view was the Pulitzer Prize–winning New York Times Magazine journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. “Never happened,” she tweeted. Jon Levine, a journalist at the New York Post, asked a reasonable follow-up question: “How can you say that? Have you reported this out? Or do you just not like Adam?” To which Hannah-Jones responded, in a now-deleted tweet: “I’ve worked at the NYT for nearly a decade. That’s how I know.”

That was more or less the level of reasoning on display on Tuesday: I know this didn’t happen. How do I know? I just know. The problem was, Rubenstein had contemporaneously told a number of people about the sandwich event, including Levine and Bari Weiss, and they started coming forward to say so. This didn’t prove it happened, but it did seriously alter the factual contours of the story: for the story to be false, it would have to be the case that Rubenstein fabricated it, at the time, well before he was in any trouble at the Times, to a bunch of his friends. Why?

Anyway, I decided to take Hobbes up on his brilliant suggestion and send an email. A few hours later, an Atlantic spokeswoman responded with a bit more information about the fact-checking process: the details of the sandwich story, she wrote to me, “were confirmed by New York Times employees who had contemporaneous knowledge of the incident in question.”

I don’t think this proves the incident occurred the way independent confirmation from someone who was in attendance would, but on the other hand, come on. The remaining skeptics are demonstrating a textbook example of an isolated demand for rigor: If something happened to a left-leaning person in 2019 that made a right-leaning group look bad, and there was this much evidence for it, of course the sandwich truthers would disseminate it without any further thought. To take one of countless examples, in 2020 Hannah-Jones helped fan an absolutely unhinged conspiracy theory about the government using fireworks to undermine the Black Lives Matter movement before (to her credit) deleting the tweet and apologizing. That theory was evidence-based enough for her to disseminate it. Hell, she had no qualms about immediately calling Rubenstein a liar — a tweet that’s still up — despite being extremely well-positioned to quietly make a call or two and learn more about this incident prior to rendering judgement. I am not particularly well-connected to the Times, but even I have dug up some further off-the-record details (update: I should have mentioned that Megan McArdle also learned more about the incident and publicly said she’s convinced it happened), and it wasn’t difficult to do so. Hannah-Jones obviously could have done the same, but it was more important to tweet and to smear.

What happened to Adam Rubenstein was, in fact, quite bad! At least by the standards of negative outcomes for someone who was in a very privileged position. He’s not a war orphan, but he did experience a pretty harrowing smearing in part because his own colleagues flew entirely off the rails. And if you look at the subset of those colleagues who are tweeting openly about all this, you’re just not seeing much remorse or reflection. Some of them are claiming that it was Rubenstein who did the smearing because of an unconvincing demand for a correction issued on Twitter by Edward Wong, a Times reporter Rubenstein criticized in his piece.1 If you’re worried about smearing, maybe raise your voice a bit when your own outlet is melting down? A lot of this concern for exacting journalistic standards seems sudden and opportunistic — where was it a few years ago?

Many journalists are exhibiting a complete lack of empathy here. I can already hear their rebuttals — something something THERE ARE WARS GOING ON AND CIVILIANS ARE DYING AND YOU’RE WRITING ABOUT A SINGLE JOURNALIST? — but that’s silly. Setting aside the fact that the people making this argument will then turn around and spend half a day ranting about a headline that doesn’t sufficiently bash Donald Trump (even though CHILDREN ARE DYING), there just have to be some standards within the halls of journalism’s most exalted institutions. If the supposed best journalists in the country care this little about the truth, and about fair and accurate reporting, what kind of message does that send?

No one in journalism would want to be in Adam Rubenstein’s shoes. It should be very, very easy for his peers to say out loud: Damn, that was unfair — that was not us at our best. Instead, there’s a lot of nitpicking and joking and denial. It’s frustrating. I’m glad that sanity seems to be returning to the media landscape, overall, but it’s still discomfiting how many journalists are not only willing but eager to publicly act in a manner that can only be described as anti-journalistic.

Questions? Comments? Requests for a five-part series on The Sandwich Incident? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

If you closely look at Wong’s claim and Rubenstein’s language, it seems Wong is upset that Rubenstein said that Wong “typically chose not to quote Cotton in his own stories” rather than that Wong “typically chose not to quote Cotton in his own stories about China,” or language to that effect. I actually didn’t find this to be the most compelling part of Rubenstein’s argument, because even as written it was rather hedged, what with that typically, but this really doesn’t seem to be correction-worthy. It would help to see the full email, but the Times and Wong don’t appear to be releasing it.

For some reason, I find the finger snapping to be the most sinister aspect of the whole story. Of course that's not the real injustice here, but it's such a concrete detail illustrating the mob mentality of the staffers.

But I can see he was treated unfairly but ALSO am a jerk. Can’t I be both, Jesse!?