Three More Gender-Dysphoria Stories, Three More Sources Of Misinformation

My last gripe about this stuff this year, I promise!

From time to time I am going to unlock older posts that were originally just for paying subscribers. When I do, I’ll create a free clone of them with comments disabled, so as to protect the privacy of paying subscribers who commented on the original. This is one such clone — it was created 12/22/2020. If you’re a paying subscriber and want to see or comment on the original, it lives here.

The only reason this post exists is because of my paying subscribers, and that’s especially true of particularly time-consuming ones dealing with subjects like gender dysphoria. So if you enjoy this or find it useful please consider becoming a paying subscriber:

All things considered, I probably spend a slightly disproportionate amount of my Singal-Minded bandwidth criticizing left-of-center media coverage of gender dysphoria that spreads misinformation and confusion about the subject. I’m never sure what the right balance is — you pay for this newsletter (which, thanks!), so if you have some thoughts, hit me up — but I do know that I’m conflicted on this subject: I’m at turns fascinated by it, exhausted by it, frustrated by it, and frequently re-motivated, by the steady stream of confused and confusing writing published on this subject in important places, to jump back into the fray once over and over. Sometimes it feels a bit masochistic.

Let’s give this one more go in 2019, with the agreement that I won’t do any more posts like this for the rest of this year. A few articles have been published recently that mess up really key stuff, and I simply want to show just how badly they misfire so as to demonstrate, once more, how little quality-control is going on in this area of media. Remember that every time one of these articles is published, more people become newly misinformed about the small subset of things we know, and the much larger subset of things we don’t know, about gender dysphoria. At a time when American culture is very interested in all sorts of questions of gender and identity and gender identity, and when record numbers of kids are showing up at gender clinics around the world, the spread of this type of misinformation is a problem for obvious reasons.

I’m going to go through one error in a Rolling Stone article, one error in a Psychological Today article, and then go through a portion of a Vox article that got a lot of really basic stuff wrong.

Come On, Rolling Stone

This Rolling Stone article by EJ Dickson is about the case of an unfortunate Texas child who has become a political football after being pulled into a rather vicious custody dispute by parents who disagree about whether he or she is trans. I’m not going to opine on the case itself, since as you’ll see it’s tangential to this post, and because it’s complicated and I haven’t had the time to carefully go through all the court documents. (This seems like a fair-minded writeup in the meantime.)

I’m happy to opine on this paragraph from the Rolling Stone article, though:

Yet during trial (and as confirmed by Judge Cooks’ ruling), [the child’s mother] stressed that she would not consider hormone suppression for her child until she reached puberty, and that she would only do so with the consent of both her and her ex-husband. Perhaps more to the point, under current guidelines gender-affirming hormones such as testosterone and estrogen are not even prescribed for children under the age of 16 and puberty blockers are not recommended until a child reaches adolescence.

The final sentence is false with regard to cross-sex hormones. The actual published guidelines, which aren’t linked to in the Rolling Stone article and which vary from field to field, often don’t say this. The Standards of Care published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, for example, don’t really provide any meaningful guidance on this front. “Adolescents may be eligible to begin feminizing/masculinizing hormone therapy, preferably with parental consent,” explains the only relevant-to-this-discussion part of the document’s section on treating kids and adolescents. “In many countries, 16-year-olds are legal adults for medical decision-making and do not require parental consent. Ideally, treatment decisions should be made among the adolescent, the family, and the treatment team.” References to age 16 don’t appear anywhere else in the body of the document.

The Endocrine Society’s clinical guidelines, meanwhile, say this (emphasis mine):

Clinicians may add gender-affirming hormones after a multidisciplinary team has confirmed the persistence of gender dysphoria/gender incongruence and sufficient mental capacity to give informed consent to this partially irreversible treatment. Most adolescents have this capacity by age 16 years old. We recognize that there may be compelling reasons to initiate sex hormone treatment prior to age 16 years, although there is minimal published experience treating prior to 13.5 to 14 years of age. For the care of peripubertal youths and older adolescents, we recommend that an expert multidisciplinary team comprised of medical professionals and mental health professionals manage this treatment.

How can Rolling Stone say that “under current guidelines gender-affirming hormones such as testosterone and estrogen are not even prescribed for children under the age of 16,” when two of the most important documents published on this subject don’t say anything of the sort? How is this accurate?

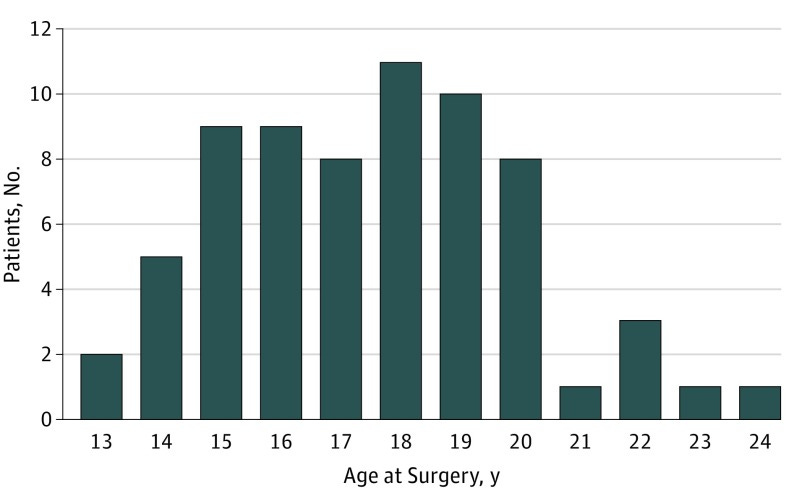

Plus, the U.S. is a wild west when it comes to trans healthcare (and, well, healthcare in general), and a lot of these guidelines are nonbinding, anyway. Everyone who follows this issue closely knows that some clinics are giving hormones to kids well under age 16, and (less frequently) some surgeons are performing surgery on minors. I know this both from voluminous anecdotal evidence from my reporting and from two papers published by clinicians at one of the most famous youth gender clinics in the country, in Los Angeles: This one shows they’ve given hormones to kids as young as 12, and this one shows they’ve referred kids as young as 13 for double mastectomies. The latter is indicated right here, in this bar graph from the paper:

I think there are some cases when kids should go on cross-sex hormones prior to 16, and am working on a (non-newsletter) article explaining why. (Surgery I’m a more leery about.) But if we’re going to have that debate, it doesn’t help to falsely tell people that “under current guidelines,” no one is going on cross-sex hormones before 16. I don’t have any hard data addressing this question — no one does — but in the United States, it wouldn’t shock me to find out that it’s actually fairly common, at the more progressive gender clinics, to start younger kids on hormones, and to refer them for top surgery.

Come On, Psychology Today

Switching gears a bit, here’s a paragraph that jumped out at me from Jack Turban’s otherwise reasonable article about how conversion therapy is bad:

There has been a shift in psychiatry over the past few decades away from pathologizing gender diversity and toward embracing it. In the past, psychiatrists referred to being transgender as a delusion. As recently as 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders referred to being transgender as a “gender identity disorder.” We no longer consider gender diversity to be an illness.

This, too, is a common and misleading trope. Ever since the DSM-5 was published in 2013, a bunch of people have falsely spread the rumor that “being transgender,” or “exhibiting gender diversity,” or some other, similar thing, switched from being a mental disorder in IV to not being a mental disorder in 5. But as I explained at length in this newsletter, when you look at the texts of the DSM-IV (where the relevant condition is “gender identity disorder”) and -5 (where it was renamed “gender dysphoria”), that just isn’t true at all. In neither document is someone considered to have a mental illness simply for “being transgender,” which is defined by GLAAD as “An umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from what is typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth.”

Rather, to qualify for either diagnosis you have to meet a bunch of other criteria pertaining to gender dysphoria, a sense of distress at being, or being seen as, (fe)male. The two categories overlap but are not the same. You can be trans without having gender dysphoria, and you can have gender dysphoria without being trans. They’re different. The DSM, in both editions, clearly attempts to pick out the category “gender dysphoria,” not the category “being trans.” While excising the word ‘disorder’ mattered to a lot of people who viewed it as a victory in their destigmatization efforts, the fact remains that “gender dysphoria” is still considered a mental disorder in the DSM. (Update, 12/22/2020: After I created the public version of this post and mentioned it to Turban on Twitter, he acknowledged the error and deleted the line in question from his post. I think he should post a correction as well — otherwise it’s a stealth edit which hides from readers the fact that he got this wrong — but at least the misinformation is no longer online. Same-day update to the update: Okay, now there’s a correction, too.)

I’m not going to repeat the entire argument I laid out in the post here — there’s a lot more detail there if you want it — but I did make a similar point to the one I nodded to above:

This rumor has spread far and wide and it’s harmful. For one thing, the fact remains that as of today, trans people who seek medical care like hormones or surgery will, if properly diagnosed, likely be tagged with a mental-health diagnosis. Maybe you think that’s fine, or maybe you think that isn’t fine, but it’s impossible to have that debate when there’s widespread confusion about what the DSM does (gender dysphoria) and doesn’t (being trans) consider to be a mental disorder. It does a disservice to trans people and their advocates to spread false information about the current situation.

Come On, Vox

This one is a bit more in-depth. It’s from a piece by Katelyn Burns on the aforementioned Texas case that gets many, many basic things wrong on multiple fronts. (Disclosure: I have a bit of frustrating online history with Burns, and if I don’t mention it here someone will accuse me of attempting to settle personal scores under the guise of media criticism. But, as I mentioned above, I’ve now done a ton of posts critiquing major outlets’ coverage of gender dysphoria. I would have taken the same approach to this Vox one whoever the author was, and the following adheres to a pretty well-established format of mine.)

I’m going to again skip over all the details of the Texas case itself to focus on the article’s broader claims about gender dysphoria. Many of the big issues start here (numbers inserted by me):

Boiling under the surface of the custody battle is a medical dispute over how best to treat and support children with gender dysphoria. Younger claimed in court that he supports the “watchful waiting” approach to dysphoric youth. Watchful waiting wasn’t given its name until 2012, but it’s (1) based on an older approach developed by Dutch and Canadian clinicians in the mid-to-late aughts that (2) suggests that parents must ensure their children perform the role of their assigned sex at birth.

(3) Under watchful waiting, a prepubescent trans girl like Luna would be forced to maintain short hair, wear stereotypical boy clothes, form friendships with boys her age, maintain her birth name and pronouns under the belief that it’s statistically likely that her dysphoria will desist by the time puberty begins. If Luna’s dysphoria does persist, only then would she be given puberty blockers, so she can mature before making a more permanent decision on hormone treatment.

(1) Burns seems to be simply confused about what the “watchful waiting” approach is. In fact, the phrase “developed by Dutch and Canadian clinicians” suggests she’s lumping together two different approaches, one developed primarily by Susan Bradley and Kenneth Zucker at the since-shuttered Gender Identity Clinic at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, and the other primarily developed by Annelou de Vries and Peggy Cohen-Kettenis at The Center of Expertise on Gender Dysphoria at the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam (another big name there is Thomas Steensma, who I’ve corresponded with a bit and have mentioned fairly frequently in my gender-dysphoria posts on Singal-Minded), and then saying that “watchful waiting” sprang forth from this combined approach.

This doesn’t really map with my understanding of this stuff, or any account of it I’ve seen anywhere. Rather, “watchful waiting” is the Dutch approach, and while there is some overlap here and there, everyone who follows this issue closely recognizes that that approach is different from the Toronto one, and that the two have been different for a long time. I don’t believe there’s any mid-to-late-aughts point at which they branched off from a prior, combined approach, in other words.

None of this is new. I mentioned the differences between the Toronto and “watchful waiting” approaches in the article I wrote about Zucker’s clinic, written when I was much more wet behind the ears on this subject, and, to take one of many other examples, Diane Ehrensaft, a famous and highly regarded youth gender clinician, wrote this in a 2017 article:

Focusing now on contemporary approaches that stand in contrast to the above mode[...] the three major models, outlined earlier, are typically referred to, in order of presentation, as the following:

The “live in your own skin” model

The watchful waiting model

The gender affirmative model

“Live in your own skin,” she goes on to explain, is Toronto, “watchful waiting” is Amsterdam, and “gender affirmative” is Ehrensaft herself. In stark contrast to Burns, Ehrensaft goes on to link the latter two, explaining that the gender affirmative model “is closely aligned with the watchful waiting model but in opposition to the live in your own skin model. Where the gender affirmative model parts ways with the watchful waiting model is in the waiting part.” Affirmers don’t like the waiting entailed by “watchful waiting,” in other words.

I do think that sometimes this cleaving is presented in a too-neat manner that obscures certain important similarities between all three approaches, but that’s not the point — the point is whatever one thinks of this conceptualization, the Vox article isn’t accurately explaining what the “watchful waiting” model is. A lot of readers are now misinformed as a result.

(2) Because this section is so fuzzy, it’s unclear which protocol, exactly, Burns is claiming would “suggest[] that parents must ensure their children perform the role of their assigned sex at birth.” But from the reader’s perspective, this protocol is closely related to “watchful waiting.” The problem is “watchful waiting,” as laid out by the Dutch in an article Burns links to in this very sentence, does not call for anything like this.

I want to be clear here: These two paragraphs contain claims about both what the “watchful waiting”-related protocol calls for and how the dad in this case interprets that protocol. Two different issues, and if the claim were simply that the dad interpreted the protocol in a too-conservative way, that would be one thing. But that isn’t what Burns is saying. It isn’t clear exactly what protocol she’s referring to, in fact, and things are about to get even more confusing.

(3) Okay, wait — so now Burns is leveling an accusation at the “watchful waiting” protocol itself (emphasis mine): “Under watchful waiting, a prepubescent trans girl like Luna would be forced to maintain short hair, wear stereotypical boy clothes, form friendships with boys her age, maintain her birth name and pronouns under the belief that it’s statistically likely that her dysphoria will desist by the time puberty begins. If Luna’s dysphoria does persist, only then would she be given puberty blockers, so she can mature before making a more permanent decision on hormone treatment.”

A lot of this isn’t true at all and reflects a severe misunderstanding of “the Dutch approach,” which I’ll use interchangeably with “watchful waiting.” The Dutch approach is absolutely more conservative on the question of social transition than the most progressive flavors of American clinical work in this area. No one is denying that. The Duch approach is premised in part on the belief that statistically speaking, gender dysphoria is likely to abate in time — Burns is correct on that front. But the approach doesn’t involve a lot of gender policing: Rather, it’s a middle-of-the-road style in which kids don’t socially transition, but also aren’t shamed or stigmatized for being who they are. These are probably the most relevant paragraphs from the linked-to article in which the Dutch lay out their approach:

Parents are furthermore advised to encourage their child, if possible, to stay in contact with children and adult role models of their natal sex as well. Moreover, we advise them to encourage a wider range of interests in objects and activities that go with the natal sex. Gender variant behavior, however, is not prohibited. By informing parents about the various psychosexual trajectories, we want them to succeed in finding a sensible middle of the road approach between an accepting and supportive attitude toward their child’s gender dysphoria, while at the same time protecting their child against any negative reactions from others and remaining realistic about the actual situation. If they speak about their natal son as being a girl with a penis, we stress that they have a male child who very much wants to be a girl, but will need an invasive treatment to align his body with his identity if this desire does not remit. Finding the right balance is essential for parents and clinicians because gender variant children are highly vulnerable to developing a negative sense of self (Yunger, Carver, & Perry, 2004). This goes especially for situations of social exclusion or teasing and bullying (Cohen-Kettenis, Owen, et al., 2003). Fortunately, social exclusion does not invariably take place, as can be seen from a recent study of gender dysphoric Dutch children (Wallien, Veenstra, Kreukels, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2010).

Parents can play a significant role in creating an environment in which their child can grow up safely and develop optimally. In this regard, it is also important that appropriate limit setting is part of the parent’s style of raising their child. For example, if a young boy likes to wear dresses in a neighborhood in which aggression can be expected, they could come to an understanding with their son that he only wears dresses at home. In such a case, it is crucial that the parents give their child a clear explanation of why they have made their choices and that this does not mean that they themselves do not accept the cross-dressing. The child will, thus, sometimes be frustrated and learn that not all of one’s desires will be met. The latter is an important lesson for any child, but even more so for children who will have a gender reassignment later in life. Although hormones and surgery effectively make the gender dysphoria disappear (Murad et al., 2010), someone’s deepest desire or fantasy to have been born in the body of the other gender will never be completely fulfilled.

This nicely captures the differences between how the Dutch and the most progressive American clinicians approach this issue — differences which are, in fact, explosive in our present political environment. In the context of a natal male child with gender dysphoria, for example, on the one hand you have the more progressive clinicians saying that you will harm your child if you don’t quickly affirm that yes, they really are a girl, because if you refuse to do so you are denying them a crucial aspect of their identity and humanity. On the other, you have the Dutch clinicians saying that you’ll possibly harm your child if you do too-quickly engage in this sort of affirmation, because they are fairly likely to desist, statistically, and shouldn’t be taught at a young, impressionable age that they are really a female in the same way a natal female is. I don’t want to downplay the importance of this difference.

But what neither group is saying is that a natally male child with gender dysphoria should be forced or coerced into “acting like” a boy. I just think this is pretty clear from the language choice above. Yes, same-sex interests (stereotypically speaking) and friends are to be “encouraged if possible.” But the language about what not to do, vis-a-vis shaming and stigmatizing, is much less hedged, at least in my reading (emphasis mine): “Gender variant behavior, however, is not prohibited … In such a case, it is crucial that the parents give their child a clear explanation of why they have made their choices and that this does not mean that they themselves do not accept the cross-dressing.” All I’m saying here is that there is a reason the clinicians are not saying that it’s ‘crucial’ to get the kid acting more boylike, but that it is ‘crucial’ to not display any disgust with his cross-dressing.

Once more: These differences in approaches absolutely matter, and should be openly discussed and debated. But I think it’s simply false to claim “watchful waiting” was developed as the offshoot of some combined Dutch/Canadian approach in the mid-to-late aughts (if you follow the citations in the 2012 Dutch approach paper, in fact, you’ll see the clinicians there had been publishing papers touching on various aspects of their general approach since well before then), and to claim that it calls for strictly enforced rules on a kid’s gendered-stereotypical behavior and expression. Vox is spreading false information about what is, and isn’t, part of the Dutch approach, as well as its history. (All that said, it’s likely true that, as Burns writes, a child at the Dutch clinic would “maintain her birth name and pronouns under the belief that it’s statistically likely that her dysphoria will desist by the time puberty begins,” since the Dutch aren’t into social transition.)

Let’s move on, again with the numbering thing:

[Watchful waiting] is based on older statistics that as many as 80 percent of children with gender dysphoria will eventually desist and grow into cisgender adults. But those numbers, according to [Joshua Safer, “executive director at the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Mount Sinai and president of the United States Professional Association for Transgender Health”], are flawed.

(1) “In terms of that desistance 80 percent comment, that’s an old Dutch study where they didn’t ask the blunt question about your gender identity to these kids,” he said. “They kind of danced around the topic with a bunch of other questions and kind of assumed they knew the gender identities, but I don’t know that it shows much of anything. It just shows that 80 percent of kids who answer questions in a stereotypical way, that you think might be associated with gender identity, end up not being transgender. But there’s a lot of bias in the questions.”(2) At issue is the fact that when the Dutch and Canadian studies were conducted, the official diagnosis for gender-variant kids was “gender identity disorder.” In order to be diagnosed with GID, a child merely had to display cross-gender dress or behavior, regardless of whether they declared themselves to actually be a member of the opposite sex. The effect of this diagnosis is that cisgender gay and lesbian children, who also frequently display cross-gender preferences without declaring themselves to be the opposite gender before puberty, were caught up in the clinicians’ studies and so of course they would “desist” later on.

[...]

(3) In 2012, gender identity disorder was changed to the less stigmatizing term “gender dysphoria,” distress resulting from a mismatch between the child’s natal gender and their internal sense of their gender identity. Nowadays, in order to qualify for a gender dysphoria diagnosis, the child must be persistent, insistent, and consistent in their gender identity over a long period of time, criteria that didn’t exist under the older diagnosis.

(1) I know Safer is a well-respected figure who has played an important role in bringing trans healthcare to young people in the U.S., but this is a pretty severe misunderstanding of the desistance literature. First, the quote “that’s an old Dutch study” makes it sound like all this is based on one study that is, well, old. The problem is, there have been multiple studies by both the Amsterdam and Toronto clinicians, all pointing in the same direction, which suggests that desistance is at least fairly common. And 2013, when the biggest peer-reviewed study on this question was published, isn’t really particularly ‘old’ by the standards of this sort of thing. Hell, the oldest study of the more recent set published by the Toronto and Amsterdam clinicians is from 2008. (As I’ve indicated elsewhere, I think that the genuinely old studies on that list should be seriously discounted relative to the newer ones, or even tossed out entirely; that people shouldn’t put too much faith in the fractions on the left because of some of the uncertainty here; and that 80% is likely an overestimate. Again, click the link if you want more details.)

More broadly, Safer is echoing a very, very well-worn trope that this literature is effectively useless because the researchers who published it lacked the tools or expertise to distinguish kids who are merely gender nonconforming (a natal male who likes to dress like a princess sometimes but has no other issues with his gender or sex) from those who are truly gender dysphoric (a natal male who likes to dress like a princess sometimes and also experiences serious distress at being called ‘he’ and having a penis). If you actually look at the studies, this just isn’t true. It isn’t true. It isn’t true!

Let’s remember that on a question like whether or not a given clinician did a given thing at a given time, in the context of research they subsequently published for the whole world to see, there is such a thing as the truth. These days, this concept — that in many situations, the truth exists — is under rather sustained attack. I’d argue it’s under the most attack by Donald Trump types, but that doesn’t mean that others aren’t falling for the same sort of fake news dynamics. We’re all human, after all. And it’s tempting! Because if you want it to be the case that this research was incapable of distinguishing GNC and GD kids — since otherwise it would deliver scientific findings you find politically unpalatable — you can simply repeat this claim over and over and over in outlets like ThinkProgress and Vox and a million others, make sure it is perceived as being deeply attached to a politically desirable position like “supporting trans kids,” and internet dynamics and human nature will do the rest. So I just want to take a sanity-check moment to reiterate that it doesn’t matter how many times the claim gets echoed in these articles or on Facebook or Twitter, or how many times people with big megaphones blast it out, or how many times people are rewarded for being on the Good Guys’ Team by angrily pointing out that Of course those studies weren’t measuring actual gender dysphoria!!!! At the end of the day, you really can pull up those studies and read them and see what they say.

I did that earlier this year in the second of two very long blog posts on this subject (here’s the first), centered around another outlet — “Science Vs” — that got some stuff wrong in its own coverage of the subject. I carefully went through and showed how, contrary to the claims made by a large and ever-growing group that ranges from anonymous Twitter users to, now, one of the most important figures in trans health, these studies did generally recognize and account for the differences between mere gender nonconformity and gender dysphoria. As is plainly evident if you read them. I’m not going to repeat all those arguments, or post a bunch of screencaps of the papers again, but it’s all right there. I don’t expect people to read my long, esoteric blog posts about gender dysphoria, but I do expect people in positions of authority to be familiar with the research they are commenting on or writing about. That’s why this is so frustrating.

(2) The key claim here is “In order to be diagnosed with GID, a child merely had to display cross-gender dress or behavior, regardless of whether they declared themselves to actually be a member of the opposite sex.” This is not true. Here it’s worth recycling this one screenshot from the DSM-IV that I included in the aforementioned post — the criteria for what used to be called childhood gender identity disorder:

The DSM-IV also explicitly cautions clinicians against misdiagnosing kids as having GID on the basis of mere gender nonconformity:

Gender Identity Disorder can be distinguished from simple nonconformity to stereotypical sex role behavior by the extent and pervasiveness of the cross-gender wishes, interests, and activities. This disorder is not meant to describe a child's nonconformity to stereotypic sex-role behavior as, for example, in “tomboyishness” in girls or “sissyish” behavior in boys. Rather, it represents a profound disturbance of the individual's sense of identity with regard to maleness or femaleness. Behavior in children that merely does not fit the cultural stereotype of masculinity or femininity should not be given the diagnosis unless the full syndrome is present, including marked distress or impairment. [emphasis in the original]

A layperson reading Burns’ claim — “merely had to display cross-gender dress or behavior” — would think that if a kid puts on a dress (which technically satisfies the conditions of that phrase), he’d get wrongly lumped in under the GID criteria. But if you look at the actual criteria rather than rely on memes and innuendo (which, remember, you can do!), you’ll see that that isn’t the case. Merely wearing a dress or engaging in other gender nonconforming behavior doesn’t get you close to reaching the threshold for this diagnosis; you also have to hit a bunch of other critera, including (D), “The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.”

I did note in my previous posts that, as just about everyone involved now agrees, the DSM-5 did slightly tighten this category. So is it possible that some kids were wrongly lumped in under the DSM-IV criteria? Sure. Was it a massive wave, seriously skewing the extant literature? I don’t see how that could possibly be the case in light of the above text and the document’s own knowledge of, and caution against, the possibility of this sort of misdiagnosis, and I’ve never seen anyone credibly defend this claim specifically in light of the plain text of the DSM-IV, rather than simply repeat it endlessly. (Interestingly, I’ve also never seen anyone concerned about the supposed near-uselessness of the DSM-IV criteria express any worries about the countless kids who must have been wrongly put on hormones as a result of being misdiagnosed; things seem to flow only in the other direction.) But again, people have now repeated this claim so often that it has become internet-true, which is, unfortunately, functionally equivalent to true-true in many contexts.

(3) Here I think Burns means 2013, not 2012 (though I could be missing something), but again, this part is just really misleading: “[After “gender identity disorder” was switched to “gender dysphoria,”] [n]owadays, in order to qualify for a gender dysphoria diagnosis, the child must be persistent, insistent, and consistent in their gender identity over a long period of time, criteria that didn’t exist under the older diagnosis.”

“Persistent, insistent, and consistent” is somewhat subjective language used to describe how clinicians approach these questions. You don’t really see anything that matches up with that idea reflected in any changes from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5, and in fact if you scroll up to the DSM-IV criteria you’ll see that that edition already used multiple instances of words with the roots ‘insistent’ and ‘persistent,’ with ‘repeatedly’ standing in nicely for ‘consistent.’ Again, it’s right there in the thing she is writing about. The DSM-5 does insert the phrase “of at least 6 months’ duration” into its childhood dysphoria category, which is a useful bit of clarification, but the earlier edition made very similar points.

Okay, last one, I promise:

Safer has said that within his previous practice in Boston and his current one in New York City, he’s seen less than 1 percent of his own patients, among several hundred cases, end up desisting. “We certainly don’t want to be taking transgender kids and not treating them because we know we’re not perfect in our understanding,” he said. “There are opportunities, again, to go slow and there’s a real range. The kids who are certain of their gender identity, those are not the kids who come back 10 years later and say that it was wrong to do the treatment.”

This is confusing two very different questions: what percentage of kids desist, versus what percentage of somewhat older people who start hormones detransition by stopping them. All the desistance studies (at least that I’m aware of) rely on samples with a lot of young kids in them who are years away from even going on blockers, let alone hormones. That’s the age range at which many experts think gender identity is at its most fluid, anyway. Safer is an endocrinologist who works with people who have gone on hormones. That’s an entirely different patient population, and one where you’d expect the gender dysphoria to be less likely to desist. To present this as a rebuttal to the desistance studies doesn’t make any sense.

It would also be useful to see Safer’s data given just how low a figure he’s claiming. I remember one other instance in which a well-known clinician made a similar claim, that their regret rate was incredibly low, and therefore some of these concerns about age and assessment and evaluation and so on were unjustified. I looked into their data and something like 40%-50% of their cohort seems to disappear, lost to followup over time, in their research (at least one peer-reviewed paper and one conference poster, off the top of my head). But if you’re not sure what is happening to a big chunk of your cohort in the long run, you can’t really make any confident claim about their regret or detransition rate — especially in a situation like this, where if a patient stops seeking care their body will automatically start to detransition itself. Plus, anecdotally, detransitioners seem to almost universally say they fall out of touch with their clinicians rather than go back to them and tell them what happened, so if you’re not hearing patients explicitly express regrets to you, that doesn’t necessarily tell you much.

I’m not saying lost-to-followup patients account for Safer’s impressive results — I’m saying it would be useful to have more information about the context in which he is presenting this claim. And, zooming out a bit as we wrap up, it’s telling which claims are taken seriously and which aren’t, in this article and others of its ilk. All the Dutch and Toronto studies, which did carefully track patients over time and explain exactly what happened to them, how they were assessed, and so on? Effectively useless, because as we all know the DSM-IV is a raging dumpster fire. A doctor claiming he has a sub-1% detransition rate, but who hasn’t published any data showing how he got this figure? Compelling evidence!

***

Motivated reasoning lies at the heart of so much that humans do. And that’s what’s going on with a lot of this reporting and commentary. It’s sloppy and harmful. The Vox article, for example, is going to get shared far and wide since it’s a big, seemingly hard-hitting take on a story and an issue that liberal-minded people are paying a lot of attention to. Of course the average reader will arrive at it knowing virtually nothing about competing diagnostic approaches to treating childhood gender dysphoria, or the DSM-IV versus the DSM-5, or why it doesn’t make sense, when asked what the desistance rate might be, to respond with the detransition rate of a patient cohort whose members all decided to go on hormones.

And now readers have been misinformed on all these issues. This is bad. Journalism should do a better job on this subject. It isn’t hard, because oftentimes the source material is right there. Anyone can read it!

Questions? Comments? Suggestions about how I can successfully cling to my last scraps of sanity? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The photograph of me reflecting on the present state of gender-dysphoria journalism is from here.