Another Gripe With How Journalists Write About Survey Research

We should be particularly cautious when zoomed-out results are music to our ears

I feel like I’m getting increasingly interested in the use and misuse of polling by journalists, and another pretty rich example just popped on my radar.

It’s in an article in The Atlantic by Ed Yong, arguably the most celebrated journalist during the pandemic and a recent winner of the Pulitzer Prize. The piece is headlined “How Did This Many Deaths Become Normal?”

I did think the framing of the piece was a bit off:

After many of the biggest disasters in American memory, including 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, “it felt like the world stopped,” Lori Peek, a sociologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder who studies disasters, told me. “On some level, we owned our failures, and there were real changes.” Crossing 1 million deaths could offer a similar opportunity to take stock, but “900,000 deaths felt like a big threshold to me, and we didn’t pause,” Peek said. Why is that? Why were so many publications and politicians focused on reopenings in January and February—the fourth- and fifth-deadliest months of the pandemic? Why did the CDC issue new guidelines that allowed most Americans to dispense with indoor masking when at least 1,000 people had been dying of COVID every day for almost six straight months? If the U.S. faced half a year of daily hurricanes that each took 1,000 lives, it is hard to imagine that the nation would decide to, quite literally, throw caution to the wind. Why, then, is COVID different?

That setup rings false to me. I guess “On some level” provides wiggle room, but does anyone think that the U.S. response to 9/11 did more good than harm? As for Katrina — maybe? But I feel like I hear a ton about our crumbling infrastructure and how ill-prepared we are for wildfires and future hurricanes and other symptoms of climate change. It just seems like a strained dichotomy used to ratchet up the argumentative tension — “Why is this particular subject different?” Maybe it isn’t! Maybe we suffer from equal opportunity suckiness when it comes to recovering from traumatizing national disasters.

Anyway, that’s just a side note. Part of Yong’s column is dedicated to pointing out the disparities laid bare by Covid, and listing some of the policies that could ameliorate them. He cites survey research to argue that many of these policies are more popular than people might think:

The inequities that were overlooked in this pandemic will ignite the next one—but they don’t have to. Improving ventilation in workplaces, schools, and other public buildings would prevent deaths from COVID and other airborne viruses, including flu. Paid sick leave would allow workers to protect their colleagues without risking their livelihood. Equitable access to antivirals and other treatments could help immunocompromised people who can’t be protected through vaccination. Universal health care would help the poorest people, who still bear the greatest risk of infection. A universe of options lies between the caricatured extremes of lockdowns and inaction, and will save lives when new variants or viruses inevitably arise.

Such changes are popular. Stephan Lewandowsky, from the University of Bristol, presented a representative sample of Americans with two possible post-COVID futures—a “back to normal” option that emphasized economic recovery, and a “build back better” option that sought to reduce inequalities. He found that most people preferred the more progressive future—but wrongly assumed that most other people preferred a return to normal. As such, they also deemed that future more likely. This phenomenon, where people think widespread views are minority ones and vice versa, is called pluralistic ignorance. It often occurs because of active distortion by politicians and the press, Lewandowsky told me. (For example, a poll that found that mask mandates are favored by 50 percent of Americans and opposed by just 28 percent was nonetheless framed in terms of waning support.) “This is problematic because over time, people tend to adjust their opinions in the direction of what they perceive as the majority,” Lewandowsky told me. By wrongly assuming that everyone else wants to return to the previous status quo, we foreclose the possibility of creating something better.

(Is it true that “people tend to adjust their opinions in the direction of what they perceive as the majority”? I find that really hard to believe — people respond to what they think their group believes, not “the majority.” I’m not saying there’s no connection or no effect, but this just seems way too pat. Look at me getting derailed again… )

“Such changes are popular” isn’t quite fully supported by the research Yong cites. This is a good example of a common (in my opinion) flawed approach to survey research. The general problem is that small changes to the way questions are worded can have very large effects on the responses. Nested within that is the specific problem: There’s a pretty big difference between asking someone whether they support generally nudging the world in a given direction versus whether they support a specific policy likely to contribute to said nudging.

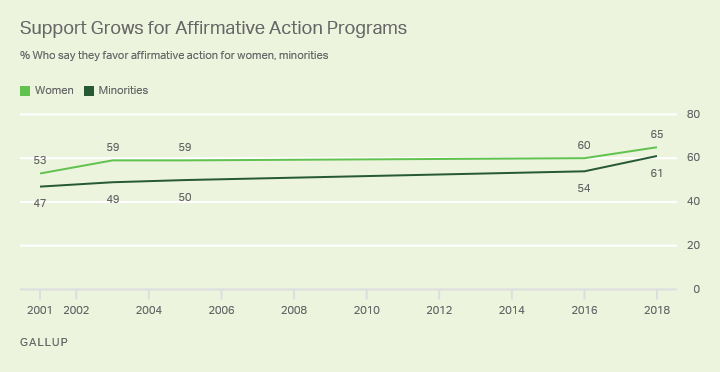

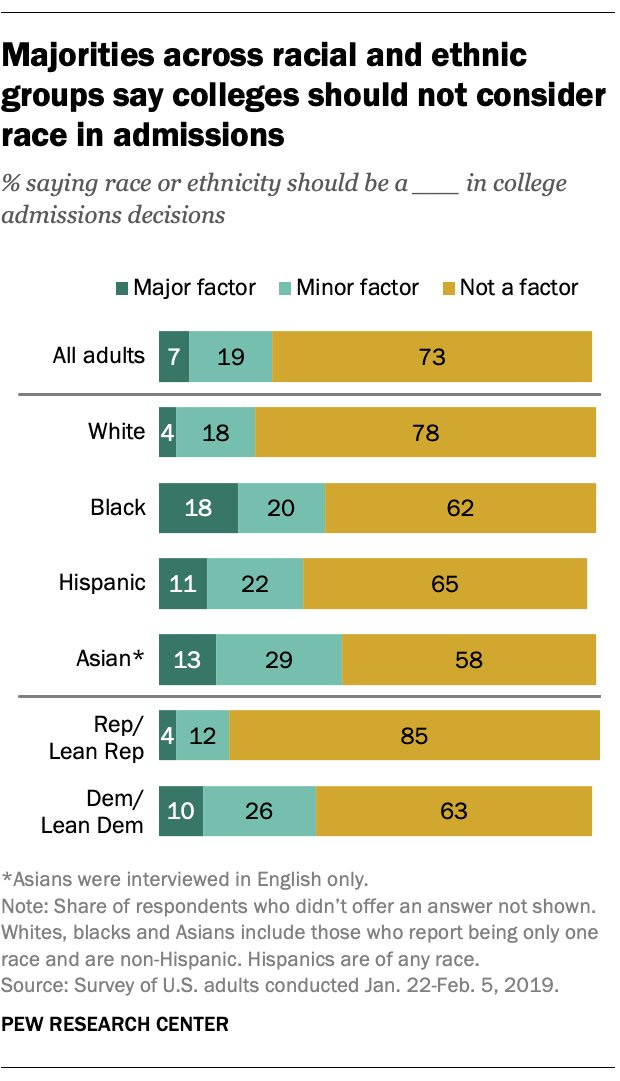

Affirmative action is a great example for this. If you simply ask people, “Do you generally favor or oppose affirmative action programs for women?” and, “Do you generally favor or oppose affirmative action programs for racial minorities?” you get supportive responses like this:

On the other hand, if you ask people how big a factor “race or ethnicity should be… in college admissions decisions,” which is another way of asking them whether they like race-based affirmative action, you get results that are incompatible with the above:

(Well, incompatible unless people have very different views on educational versus non-educational affirmative action, which seems unlikely.)

If even describing (basically) the same thing in different words can generate such different results, surely there’s a difference between, for example, “Do you favor policies that will help kids thrive in schools?” and, “Do you favor a $100 million increase in funding for Boston schools?” So even if a majority of people say that they’d prefer us to make the world better than it was before Covid, rather than merely have it return to how it was, I think there’s a lot of reason to be skeptical that that means much of anything with regard to the likelihood that Yong’s preferred policies will come to pass.1

And when I dug into the results more closely, it only shook my optimism further. For the sake of simplicity, let’s focus on the first of the two experiments in the paper, since the researchers replicated the results (in a slightly different way) in the second.

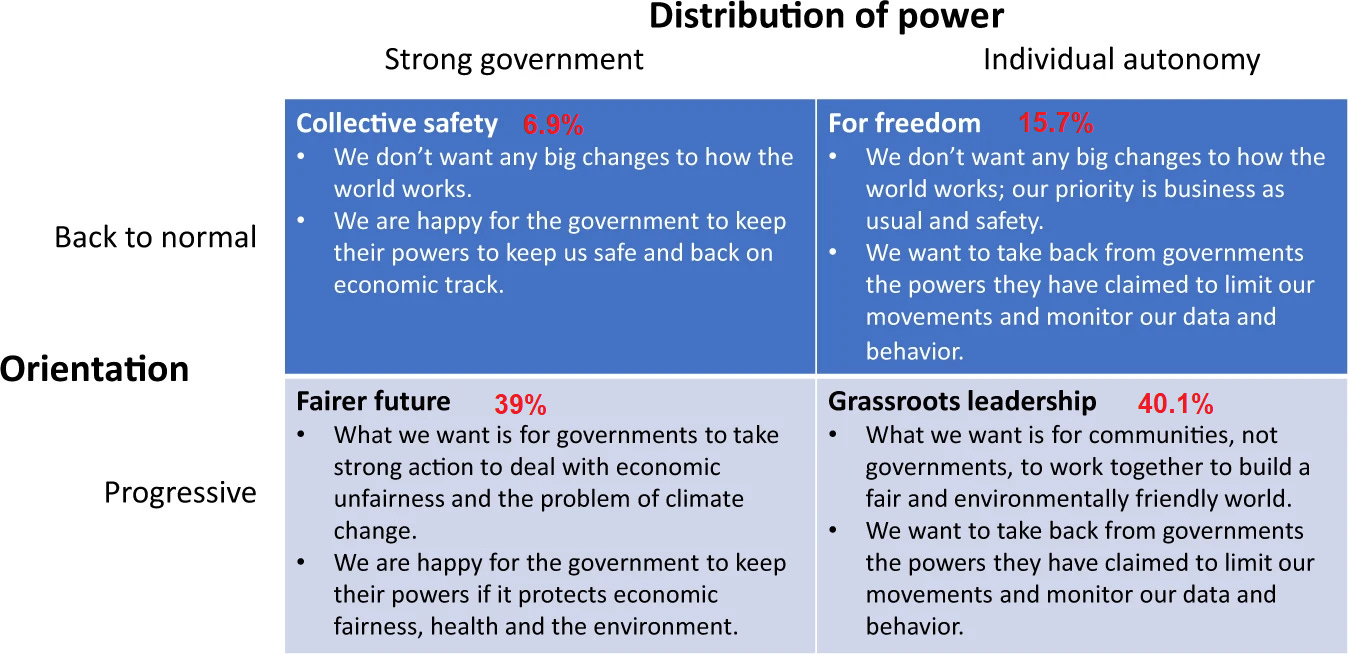

In the first experiment, respondents simply were asked to read four scenarios and to pick the one they favored. I’ll put the results for Americans in red, over the graphic the researchers included that summarizes the four scenarios. (The supplementary materials are here if you want to read the prompts verbatim.)

(If you have trouble reading the chart, the results are 6.9% for “Collective safety,” 15.7% for “For freedom,” 39% for “Fairer future,” and 40.1% for “Grassroots leadership.”)

In terms of analyzing these results from a common sense perspective, the first thing to note is that the “Progressive” choices gobbled up almost 80% of the total vote. From an American perspective, that’s insane. I’m not aware of any as-yet-unimplemented mainstream policy proposal that garners the support of anywhere near 80% of the American electorate, and of course neither Democrats nor Republicans claim anywhere near 80% of Americans as members of their party. So we should immediately ask whether this can tell us anything about our very polarized American political landscape — and I’m skeptical that it can. It could just be that if you ask people during a moment of profound crisis and uncertainty if they’d prefer the status quo or a better world, they’ll pick a better world, because why not?

Now, this whole thing is rendered a little weird and confounded by the fact that there’s no option for “I’d like the government to address inequality and climate change, but to cede the powers it seized during Covid,” or for “I’m okay with the government seizing temporary power to deal with Covid, but not with it taking an active role addressing economic inequality and climate change.” The options are sort of everything or nothing, government-wise, and that dichotomization could contribute to the runaway success of the “Progressive” options.

But of the four scenarios, the most popular one — by a smidgen — was actually “Grassroots leadership,” which called for building a better world but one with little government involvement. So of the group of about 80% of respondents who wanted a better world rather than the same world post–Covid, half of them weren’t interested in big government solutions—which would wipe out most of Yong’s preferred policies, unless I’m seriously missing something.

Now, that other point Yong raises about the discrepancy between people’s own policy goals and their prediction of others’ is certainly interesting, and it ties in to a lot of other findings that people aren’t good at judging others’ beliefs or intentions. But overall, this is a useful example of how careful journalists should be about overextrapolating from this sort of 50,000-foot-view polling.

We should be on guard particularly when we are interpreting a polling result — or any scientific result — as telling us something we want to be true. I would love for it to be the fact that Americans really wanted the same policies I want, and that pluralistic ignorance was the only thing really holding us back from a better, more progressive nation. But the reality is a bit different, and a bit tougher to address. It’s not as good a story, and definitely a less inspiring one.

Questions? Comments? In-depth polls picking apart my most intimate flaws? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Image: Photo of a finger pressing a smiling face, with a neutral face and a frowning one to the right, comes from Getty.

To be clear, some of them are popular! Paid family leave and a robust government role in guaranteeing everyone has access to healthcare both poll well, as do some other progressive policies. I do think that as a policy proposal on a hot-button subject edges closer to reality it becomes quite policitized, meaning that people who support it in the abstract might come to view it as opposed to their political identity and flip-flop as a result.

I have not enjoyed reading Ed Jong's pieces lately. I feel like he is completely out of step with mainstream normies.

I work in an elementary school as a nurse, and Covid/contact tracing had utterly consumed my life for awhile. But now? Nobody gives a shit anymore. In my little corner of Southwestern PA, anyway.

All of the heated fights and community unrest that was present in the Fall are over now. Nobody wants to be in a defensive crouch for years. The unspoken agreement seems to be that we all need to move on. Covid is here to stay, and we are not doing all the shenanigans anymore.

I think that's a very normal, human, earth animal way to deal with things.

I want more goodness and less badness and I would like it done by people doing things that are right and not doing things that are wrong. This is my very specific and practical policy position and if you can’t accept it you are a monster.