Yale’s “Integrity Project” Is Spreading Misinformation About The Cass Review And Youth Gender Medicine: Part 2 (Corrected)

We deserve better from experts, some of whom have completely mortgaged their credibility

This sort of work is extremely time- and resource-intensive. If you find it useful, please consider becoming a paying subscriber or giving a gift subscription to someone who might benefit from it.

To my paying subscribers — thank you so much. Simply put, you’re the reason I’m able to do this. If you haven’t read Part 1 yet, what follows will make a lot more sense if you do. And Part 3 is now available here.

I thought this was going to be a two-part series, but it’s now going to be a three-parter. There’s just too much to discuss.

To review, this is a critique of a July 1 white paper entitled “An Evidence-Based Critique of ‘The Cass Review’ on Gender-affirming Care for Adolescent Gender Dysphoria.” It was published by The Integrity Project, a Yale Law School center co-founded by Meredithe McNamara, an adolescent medicine physician at Yale, and Anne Alstott, a legal scholar at Yale Law School, and lead-authored by Meredithe McNamara. (They are the only two scholars listed on its “People” page.) The white paper is co-authored by McNamara, Alstott, and seven others. While it’s not peer-reviewed, this is an important document, because it reflects the views of some of the top youth gender medicine clinicians and researchers in the country — experts who are frequently quoted and consulted on this issue — including Johanna Olson-Kennedy, Jack Turban, Kellan Baker, and Aron Janssen.

In addition to having an outsize influence on the national debate about this subject (both via their comments to media and their expert testimony in court cases), a number of the authors on this white paper routinely provide puberty blockers and/or hormones to minors. The public has a right to expect that such a highly respected, frequently consulted group will be well-informed about the controversies surrounding youth gender medicine, and able to communicate those controversies accurately and in a good-faith manner. That didn’t happen in this white paper — not even close.

This document deserves the deep dive I’m giving it because it rather jarringly captures the extent to which experts have mortgaged their credibility on this issue. Many of the claims made by McNamara et al. are either recitations of activist talking points that have been debunked outright, or severe exaggerations of the available evidence. Taken as a whole, it’s quite disturbing that these authors published this document, that Yale Law School then threw its weight behind it, and that McNamara filed a version of it in the legal case Boe v. Marshall.

On top of all of this, the authors have posted substantively different versions of the white paper on the Yale website at different times. When I reached out, Alstott claimed that this was a version-control error and the wrong draft had been posted to the site for a month and a half. There’s no good reason to disbelieve her, but this only further reinforces the unprofessional, sloppy nature of this effort. It is a violation of basic norms of transparency in publishing (whether journalistic or academic) to allow substantively different versions of the same document to float around online without logging the changes and explaining them, and to this day the version of the document filed in the court case remains different from the one posted on the Yale website. (More on this shortly.)

In Part 1 I focused on McNamara and her team’s many undisclosed conflicts of interest as well as the objectively false claims they make about the contents of the Cass Review. In Parts 2 and 3, I’m going to focus more on the many claims in the white paper that aren’t objectively false, per se, but that represent severe misunderstandings or misinterpretations of the Cass Review, the principles of evidence-based medicine (EBM), or both.

In this article, first I’ll explain some important principles of EBM, then simply go through the white paper in roughly chronological order, attempting to critique it in as comprehensive a manner as possible. Similar to last time, when McNamara and her colleagues make fair critiques of the Cass Review, I’ll acknowledge that.

There’s a lot to get to, so I’ll finish everything up in Part 3.

A Quick Primer On Evidence-Based Medicine

(This section is skippable for readers who are already familiar with EBM.)

In short, evidence-based medicine is “the application of the best available research to clinical care.” For most of the history of medicine, EBM proponents argue, doctors have not rested their clinical decision-making on quality evidence the way they should have. Sometimes they have relied on their own observations about how their patients fare following treatment, sometimes they have relied on poorly conducted studies, and sometimes they have relied on the views of other doctors. All of these methods of determining the best medical treatment(s) for a given patient are highly susceptible to human bias in a manner that well-executed, carefully controlled studies are not. (In partial defense of the doctors of yesteryear, many of them didn’t have access to modern methodological innovations.)

In Part 1 of this series, Dr. Gordon Guyatt, a McMaster University professor and one of the creators of EBM, explained that doctors’ opinions about medical treatment have often been governed by GOBSAT, or “good old boys sitting around a table,” rather than more rigorous methods. Medicine has wandered down many dark alleys, sometimes with tragic results, because of this sort of hubris and groupthink. While the proportion of “boys” in medicine may have fallen over time, human nature is still human nature, so it’s important to recognize such dynamics as a ubiquitous ongoing risk to the quality of care medical patients receive.

So from an EBM perspective, doctors should rely on carefully conducted studies and, more importantly, summaries of studies. One of the key principles of EBM is that there are very important differences between studies that are rigorously conducted and those that are not. If a study finds that Pill X improves insomnia, but there are significant flaws with the study’s design, the study offers us very little meaningful evidence that Pill X improves insomnia. If five new, similarly weak studies demonstrating Pill X’s benefits are published, that doesn’t get us much closer to the truth of the matter. In fact, a single, very carefully conducted randomized controlled trial can tell you more about a treatment’s efficacy than a pile of weaker studies. (For a tragic example of this that will likely come up in my book, see False Hope: Bone Marrow Transplantation for Breast Cancer.)

To be fair, medicine isn’t the only area of science that has frequently fallen victim to excitement over some new treatment or intervention on the basis of shoddy studies that did not stand up to scrutiny. My book included many examples of this from psychology. So I’m not saying this is a unique problem to medicine, and within medicine it’s definitely not a unique problem to youth gender medicine in particular (if you think otherwise, get yourself some Ben Goldacre).

What I am saying is that in 2024, just about everyone involved in medical research is aware of the sorts of problems highlighted by the EBM movement, and that simply cherry-picking studies you like can lead to a seriously skewed understanding of the available evidence. If a researcher doesn’t know this in 2024, they simply shouldn’t be conducting research. If a doctor advocating a treatment doesn’t know this in 2024, they should not be taken seriously. It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking cardiology, immunology, oncology, or gender medicine — the same principles apply.

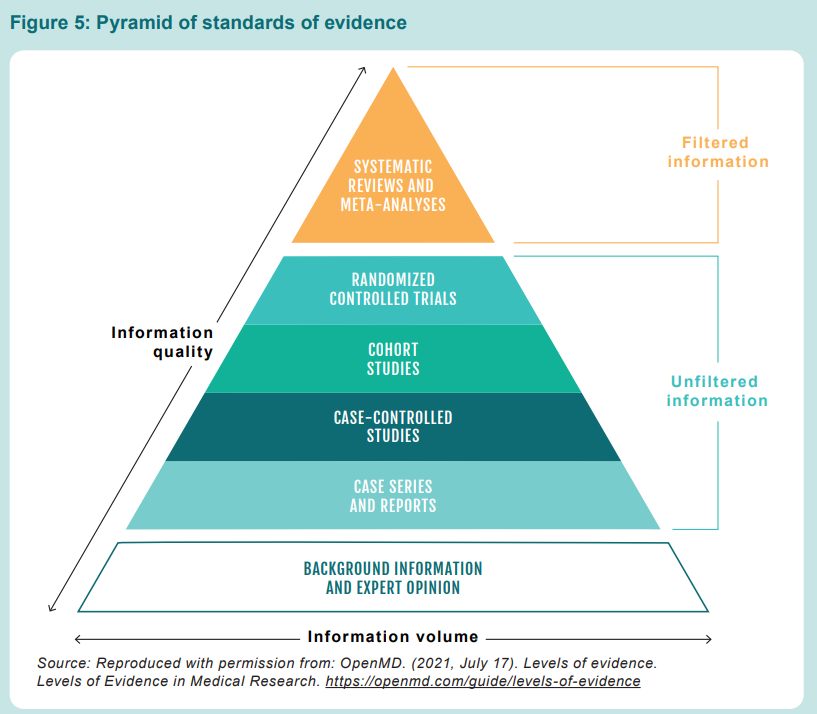

EBM has established a clear hierarchy elucidating the differences between weaker versus stronger types of evidence. Hilary Cass and her team include this pyramid in their report:

Throughout their white paper, McNamara and her team seem incapable of grasping this. Early on, referencing the subset of the paper’s authors who are youth gender clinicians, they mention “the positive clinical outcomes that our patients experience.” Who says they’re positive? On what basis? The whole point of EBM is that the public — and more importantly, patients themselves — shouldn’t have to rely on the say-so of doctors. “Background information and expert opinion” is next to useless when it comes to high-stakes debates about medicine. Keep that in mind as you read what follows.

The systematic reviews of youth transition commissioned by the Cass Review and conducted by the University of York, like those conducted by the other European countries I mentioned in Part 1, sought to evaluate the available evidence in as unbiased a manner as possible. Does that mean these SRs were perfect? Of course it doesn’t — there’s no such thing as a perfect systematic review. But they, and the broader report they are a part of, should be critiqued from a knowledgeable perspective.

Instead, as we’ll see, Meredithe McNamara and her colleagues seem to have a lackluster understanding of the basic tenets of evidence-based medicine. Making matters worse, they repeatedly misunderstand and/or misstate the extant literature on youth gender medicine.

A Summary Of McNamara Et Al.’s Misunderstandings And Misstatements

Early in their paper, McNamara and her colleagues attempt to argue that there’s no genuine controversy about one of the most important themes of the Cass Review — whether and how rigorously youth are assessed prior to being put on blockers and hormones — because everyone in their world agrees that assessments are quite important.

This comes up on multiple occasions. Early on, McNamara and her team argue that “The holistic care that the clinicians among us provide is rooted in decades of research” [page 3, bracketed page numbers throughout refer to pages in the McNamara et al. white paper, citations omitted throughout and emphasis in the original throughout]. A bit after that, they argue that “The Review concurs with the WPATH Standards of Care and the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines that: (1) medical care is appropriate for some transgender youth, (2) a holistic, comprehensive, and individualized assessment is needed, and (3) co-occurring mental health conditions should be properly treated before medically affirming interventions.” [4]

A bit after that, they write:

Indeed, statements of the Review favorably describe the individualized, age-appropriate, and careful approach recommended by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and the Endocrine Society. [2]

. . .

The Review explicitly notes that, “for some, the best outcome will be transition” (p 21) while also acknowledging, as the WPATH Standards of Care and the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines do, that gender-affirming medical interventions are not appropriate for all transgender adolescents. This is an essential point, as many who criticize this care inappropriately contend that medical consensus endorses medical transition for any minor seeking care. The Review states, and indeed WPATH and the Endocrine Society agree, that “there should be a clear rationale for providing hormones at this stage rather than waiting until an individual reaches 18.” (p 187)

While the Review contains some non-technical language regarding gender-affirming medical interventions, it is essential to note that this language is followed by recommendations to conduct thoughtful, cautious assessments prior to considering medical care, rather than banning care or not providing it altogether. [5]

McNamara and her colleagues’ overall argument is that there isn’t really much to see here. WPATH agrees there should be robust assessment, the Endocrine Society agrees there should be robust assessment, the Cass Review agrees there should be robust assessment. . . what’s the problem, even?

But this is divorced from reality. First, it’s well-established that at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS), the clinic at issue, there was significant variation in the level of care that youth received, including whether and to what extent they went through comprehensive assessments.

In the interim Cass Review, Cass wrote:

1.7. At primary, secondary and specialist level, there is a lack of agreement, and in many instances a lack of open discussion, about the extent to which gender incongruence in childhood and adolescence can be an inherent and immutable phenomenon for which transition is the best option for the individual, or a more fluid and temporal response to a range of developmental, social, and psychological factors. Professionals’ experience and position on this spectrum may determine their clinical approach.

1.8. Children and young people can experience this as a ‘clinician lottery,’ and failure to have an open discussion about this issue is impeding the development of clear guidelines about their care.

So no, comprehensive assessments were not the established norm at GIDS or in other parts of the NHS youth gender system. That’s also true in the United States. As Reuters reported in 2022, even the big, multidisciplinary youth gender clinics said they were willing to refer a young person for blockers or hormones on the first visit in some cases, which deviates wildly from the so-called Dutch Protocol, which is where the only semi-decent evidence for youth gender medicine comes from.

All this has occurred at a time when, as Reuters put it,

[M]any of the patients flooding into clinics wouldn’t meet Dutch researchers’ criteria. Some have significant psychiatric problems, including depression, anxiety and eating disorders. Some have expressed feelings of gender dysphoria relatively late, around the onset of puberty or after, according to published studies, gender specialists and clinic directors. Such cases require more extensive evaluation to rule out other possible causes of the patient’s distress.

I have regularly encountered examples of this in my own reporting, some of which will be in my book. I’ve spoken with a number of parents who took their gender-questioning kid to the local gender clinic (often after an extended and frustrating wait), expecting an introductory conversation about the options available to them, only to find that on the first visit, the clinicians or social workers they spoke with were ready to put their kids on puberty blockers and/or hormones immediately. This appears to be a fairly common occurrence in the States.

So it’s strange that McNamara and her colleagues would describe this matter as settled. And what’s even stranger is that several of the authors themselves have publicly said they don’t believe in the importance of comprehensive assessments for young people considering youth gender medicine!

They aren’t shy about expressing this view. Take Johanna Olson-Kennedy, for example. She is the medical director of a major youth gender clinic at UCLA as well as a co-principal investigator on the largest ongoing federal research effort into youth gender medicine (which will come up later).

When I interviewed her for my 2018 Atlantic article about this subject, she told me that she does not believe in mental-health assessments for TGNC youth seeking medical intervention, reiterating an opinion she had previously laid out in print:

In “Mental Health Disparities Among Transgender Youth: Rethinking the Role of Professionals,” a 2016 JAMA Pediatrics article, she wrote that “establishing a therapeutic relationship entails honesty and a sense of safety that can be compromised if young people believe that what they need and deserve (potentially blockers, hormones, or surgery) can be denied them according to the information they provide to the therapist.”

This view is informed by the fact that Olson-Kennedy is not convinced that mental-health assessments lead to better outcomes. “We don’t actually have data on whether psychological assessments lower regret rates,” she told me. She believes that therapy can be helpful for many TGNC young people, but she opposes mandating mental-health assessments for all kids seeking to transition. As she put it when we talked, “I don’t send someone to a therapist when I’m going to start them on insulin.” Of course, gender dysphoria is listed in the DSM-5; juvenile diabetes is not.

In 2021, Jack Turban went on the GenderGP podcast, which is hosted by the British general practitioner and youth gender medicine activist Helen Webberley, who lost her license to practice over this issue (though here’s her side of the story). During that podcast, Webberley says that “basically Johanna [Olson-Kennedy] has just said, look, if your kid, if your kid tells you that they’re trans, they most likely are. Just believe it.” This is a secondhand description of Olson-Kennedy’s clinical practice, of course, but it tracks closely with what she has written and said on the record.

Based on his own statements during the interview, Turban seems to be in agreement with Olson-Kennedy’s approach: He criticized youth gender care that is “really focused on like assessment and gatekeeping” and pointed out that

[M]ost of the models in the US still do use a model based on the Amsterdam model where somebody has to be in therapy for six months and come with a letter. And the letter says that like, they really are transgender, have gender dysphoria and meet the WPATH guidelines. And then psychiatry, I would say, that’s still, where are most of the US is, but there are a few clinics, and mostly pediatrics, adolescent medicine specialists who are moving away from that and doing more of an informed consent model, like what people do [with] adults where they’ll sit down, they’ll tell the person, listen, these are what these medical interventions do. This is what they don’t do. These are all the potential implications for your health, you and your family go discuss them, like, come back, we’ll make sure that you really understand all the intricacies of this. And then if you have all the information and you know, all the risks and benefits, then, then you don’t need to be in therapy for six months, but it’d be great if you have a therapist, like kind of support you through this process, because it’s really hard to, because most of society is awful. And sometimes people need help navigating that. So there’s definitely a tension between those two approaches right now. And I think it’s just going to take a little bit more time to see how it all evolves.

Turban has been clear, in multiple contexts, that he is in favor of what would, in effect, be an “informed consent” approach for youth (technically, minors in most states can’t provide “informed consent” the way adults can, but the point is that he is decrying undue “gatekeeping” even for minors). In a research study on puberty blockers he lead-authored, he and his team wrote that their results “strengthen[ ] recommendations by the Endocrine Society and WPATH for this treatment to be made available for transgender adolescents who want it.” The authors are badly oversimplifying the Endocrine Society and WPATH guidelines, but I would argue this reflects his true view: puberty blockers and/or hormones should be given to “transgender adolescents who want them,” without the meddling of potentially stigmatizing psychologists, doctors, or other gatekeepers.

In Turban’s recently released book, which I haven’t read but which Ben Ryan has, he also argues against assessment:

At the end of the day, we don’t have a clear data-driven answer regarding the utility of requiring a biopsychosocial assessment and mental health letter prior to starting pubertal suppression. For just about every other medical intervention in pediatrics, we don’t take this approach. Instead, we take an “informed consent” approach, in which the parents and adolescents are told, by the prescribing doctor, all the risks, benefits, and potential side effects of the medication. The family then weighs these and decides on the best course of action for their adolescent child. Usually, an additional mental health professional doesn’t need to be involved.

Most readers will recognize this as a bizarre analogy. A minor cannot, in fact, walk into a pediatrician’s office, announce they have some condition, and then commence treatment after they and their parents sign some forms.

Part of what’s strange about this is that when Turban was asked, under oath during a deposition, if he could think of a situation in which other mental health problems might interfere with diagnostic clarity in a youth gender medicine context, he readily summoned an example from his own experience. After noting that he was changing certain details due to privacy concerns, Turban explained that one of his patients

enjoyed ballet, like a stereotypical female activity, and wondered if that meant that he was trans. The more we talked to him, we realized that no, he just likes that particular activity, but still very much identified as male and certainly didn’t actually have a disconnect between his gender identity and his sex assigned at birth. Certainly didn’t have any problem with his physical body or primary or secondary sex characteristics. And the more we talked through it, it seemed clear, you know, he didn’t have gender dysphoria. But maybe at first glance he did have suspicion for it because of how he was describing this rigid thinking around gender roles’ [sic in transcript] behavior.

Turban presented this realization as one that occurred to him and his peers over time, as they got to know this kid. This sounds like a. . . thorough assessment. So Turban is inconsistent on this issue, and sometimes appears to talk out of both sides of his mouth, but in his public statements he has tended to express significant skepticism toward assessment.

Meredithe McNamara, meanwhile, told Chris Cuomo that “Kids know their genders — unequivocally.” The whole theory of youth gender medicine is that it aligns young people’s bodies with their “real” (felt) gender. So if kids know their genders unequivocally, what possible reason could there be to subject them to comprehensive assessments prior to providing them with blockers and hormones?

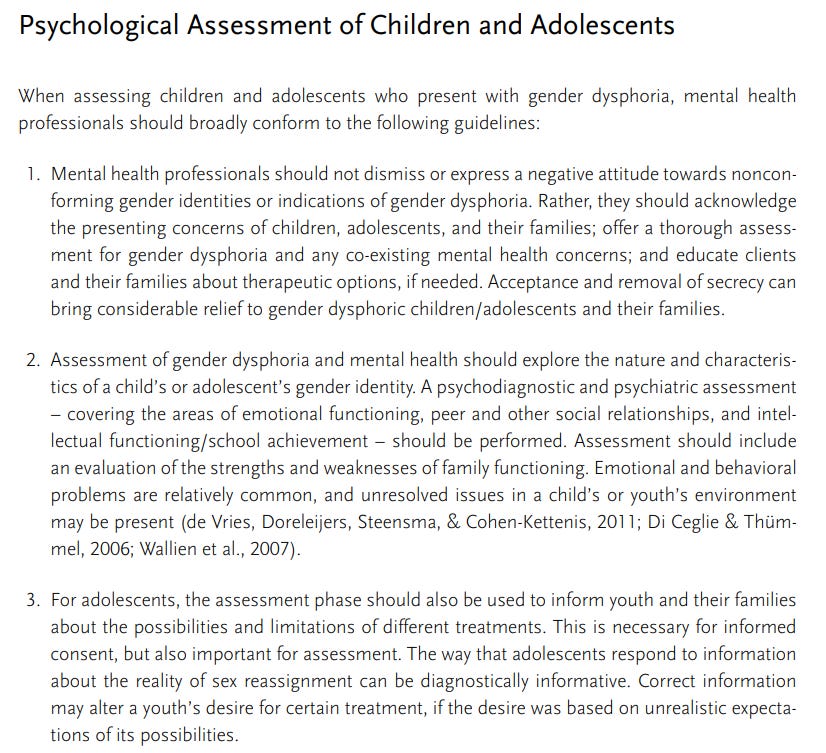

McNamara and her co-authors are being a little bit slippery in their language here by referencing written standards, which often do nod to the importance of assessment, rather than their own opinions. But these standards are totally nonbinding and have tended to be quite vague. The second most-recent version of the World Professional Association for Transgender Healthcare’s Standards of Care, Version 7, had almost nothing about assessment.

This was the entire section on that subject:

The SoC 8 offers a considerably beefed-up treatment of this subject, but its predecessor clearly indicates that youth gender medicine assessment was, for a significant period, not a major priority or concern for WPATH.

The Endocrine Society’s current guidelines, meanwhile, call for assessment by trained mental-health practitioners prior to the administration of blockers or hormones, but offer almost zero guidance on exactly what that assessment should entail. There’s just almost nothing there.

So overall, McNamara and her team paint a clear picture that basically all the experts agree that comprehensive assessments prior to youth gender medicine are important. That just isn’t the case. In fact, there’s rather fierce disagreement on this, which is part of the reason the Cass Review came about in the first place.

***

McNamara and her colleagues write:

Most of the Review’s known contributors have neither research nor clinical experience in transgender healthcare. The Review incorrectly assumes that clinicians who provide and conduct research in transgender healthcare are biased. Expertise is not considered bias in any other realm of science or medicine, and it should not be here. Further, many of the Review’s authors’ identities are unknown. [footnote] Transparency and trustworthiness go hand-in-hand, but many of the Review’s authors cannot be vetted for ideological and intellectual conflicts of interest.

[Footnote:] Following the completion of the “research programme” by the University of York, “A Clinical Expert Group (CEG) was established by the Review to help interpret the findings” (p 26), defined as “clinical experts on children and adolescents in relation to gender, development, physical and mental health, safeguarding and endocrinology” (p 62). There is no further information about the qualifications of the members of the CEG, nor how they were selected. [3]

This one’s more complicated — a mix of fair points and misunderstandings on the part of McNamara and her team.

Correction: What I wrote below is false. I’m crossing it out but leaving it readable for transparency’s sake. The systematic reviews did include someone with clinical experience in youth gender medicine: As the protocol for the York systematic reviews notes in its ‘Conflicts’ section, “Dr Trilby Langton is a former Clinical Psychologist at the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service.” Langton is a co-author on all the systematic reviews. This was a careless error on my part and I apologize for it.

The fair points: First, yes, ideally a systematic review will include an author who is a subject matter expert, and the York University systematic review authors were all methods experts rather than youth gender medicine experts.

“It’s problematic” not to have a subject matter expert as a co-author on a systematic review, Gordon Guyatt told me. “Periodically we see reviews that don’t have adequate content expertise as part of the team mess up because they do not grasp the subtleties, or not-so-subtleties, about the content area.” Not doing so “puts you at risk of not having full insights into the content,” he said, though “whether that risk plays out as a problem or not is another question.” (I’ll argue in Part 3 that the McNamara team’s specific claims about problems with the York SRs don’t generally make sense.)

Gordon Guyatt also agreed with McNamara and her colleagues that the names of the CEG’s members should have been public. “Because it’s a community, right?” he explained. “Presumably, you would want all views to be — all credible views, anyway — to be represented. And were you to have decided what you wanted to say in advance, it would not be difficult to pick. . . a restricted range of experts that adhere to your particular views.” That doesn’t mean Cass and her team did this, of course, but because they weren’t transparent about who was on the CEG, it’s a perfectly fair question to ask — especially given that this team apparently played a key role translating the SR views into the content of Cass’s published report. By not including the names, we can only wonder. (As I noted in Part 1, I reached out to the Cass team and they did answer some of my initial questions, but eventually said they were going media silent until an in-progress, peer-reviewed critique of the McNamara et al. white paper is published.)

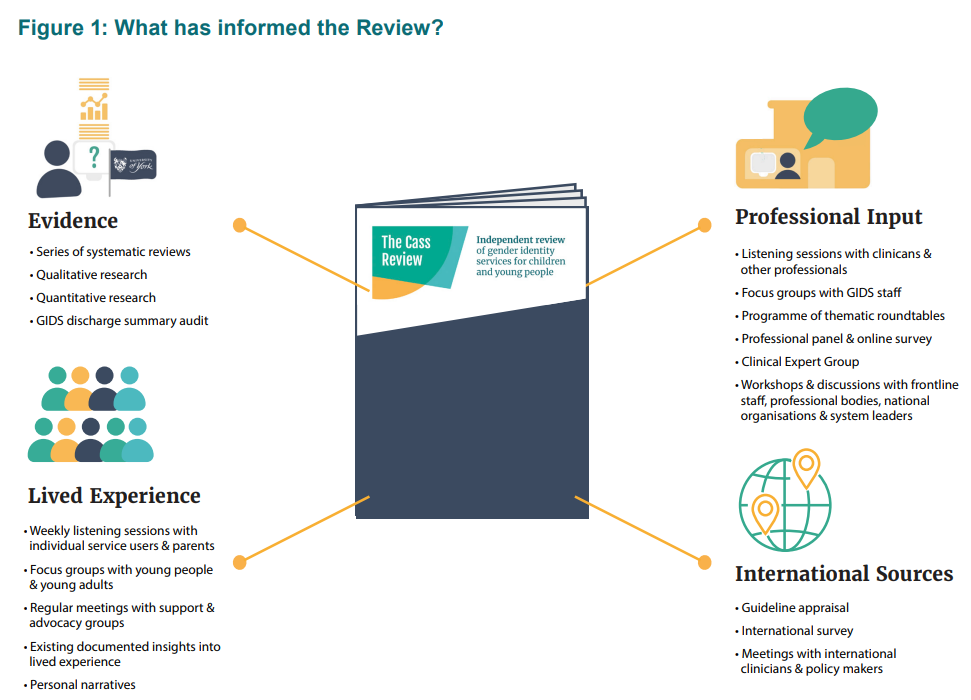

All that being said, McNamara and her team seem to misunderstand the Cass Review’s approach to expertise and bias. As far as I can tell, nowhere does Cass express anything that could be construed as the “assum[ption] that clinicians who provide and conduct research in transgender healthcare are biased,” and during the the broader process of preparing the review, Cass and her team clearly interviewed experts with a wide range of views on this subject:

If I had to guess, McNamara and her colleagues are referencing both the fact that Hilary Cass herself had no prior experience in youth gender medicine, and the aforementioned lack of subject-matter experts. And in doing so, they’re ignoring the importance of avoiding conflicts in this sort of effort.

Cass was, as has been previously noted, chosen to head up this review in part because while she was a broadly respected pediatrician, she didn’t have experience in youth gender medicine. If you believe that doctors can be intellectually or financially conflicted with regard to certain treatments, that makes perfect sense — you wouldn’t want to choose someone who had a prior reason, entering the process, to come to a conclusion favoring or disfavoring these treatments.

Similarly, while it might be fair to criticize the York SRs for not having subject matter experts as co-authors, they did follow a standard rule of SRs by not including anyone with a potential conflict. “While systematic review teams require members with content area expertise, they must avoid those with financial or intellectual conflict of interest,” Guyatt said in an earlier email. “For example, many methodologists would exclude authors of studies eligible for their review from the review team.”

My own view, knowing nothing about the York SR team’s process of picking authors (they did not respond to an emailed inquiry), is that in practice it would have been difficult to pick a subject matter expert in youth gender dysphoria who would not elicit cries of “Bias! Conflict!” from one party or another. (Post-correction update: Sure enough, there are complaints on social media about Langton.) And if the York teams made major blunders as a result of their lack of subject-specific knowledge, you’d think McNamara and her colleagues could come up with compelling examples. As we’ll see later, they fail to. And not to understand the difference between “We kept potentially conflicted individuals away from this evidence review” and “Anyone in this area of medicine is inherently biased” speaks poorly of McNamara and her team’s knowledge of EBM and ability to read the Cass Review accurately.

***

A consistent problem throughout McNamara and her colleagues’ white paper is that they make authoritative-sounding statements about subjects that are still shrouded in a great deal of uncertainty.

For example:

There is no evidence that co-occurring mental health conditions cause a person to adopt a transgender identity, nor is there evidence to support that treatment of co-occurring mental health disorders ameliorates the core symptoms of gender dysphoria. Individual patients require treatment plans that are tailored to the diagnoses made by qualified professionals. [6]

Scott Alexander has a really good essay on the term no evidence, which he argues is a “red flag for bad science communication.” Saying there is “no evidence” that something is true often provides. . . well, very little evidence that the thing isn’t true. To borrow an example from him, in terms of peer-reviewed studies, it is true that there is “no evidence” that if you jump out of a plane, wearing a parachute does a better job keeping you alive than not wearing a parachute. After all, there’s never been an RCT on this question — thankfully for those who would have been randomized to the control group. (Correction, 12/9/2024: I was wrong! A reader pointed out back in September that the British Medical Journal published a very cute RCT designed to make nerdy but important points about what we can and can’t extrapolate from this sort of study. At the risk of spoiling the study for you, it did not involve humans jumping out of planes at high altitudes without parachutes. I kept forgetting to add this correction and I apologize for the delay.)

What McNamara and her colleagues are saying isn’t nearly as silly as this example, but the fact remains that it is an extremely overconfident proclamation given how little is known about youth gender identity formation, as well as the existence of countervailing evidence. Now, is that countervailing evidence anecdotal, for the most part? Yes — but so is the claim that there’s no link between mental health problems and transgender identities or GD.

Clinicians who have worked closely with transgender and gender nonconforming youth have long noted that in at least some cases, other mental-health conditions can impact gender identity or even cause a transgender identity. Here, for example, is Diane Ehrensaft — a leading gender-affirming psychologist who works with Turban at UCSF and who has published with both him and Olson-Kennedy — in her 2011 book Gender Born, Gender Made: Raising Healthy Gender-Nonconforming Children:

Studies have shown that children have been known to insist on a change in gender or become gender-confused after a trauma or major disruption in their attachments. For example, a three-year-old boy survived a serious car accident that his mother did not. Afterward, he started insisting he was a girl. Before that, he never indicated any gender-nonconforming behavior. Now, to reclaim his dead mother, he became her. There is no doubt that children like this little boy did not just roll into the world as gender non-conforming, like those in parents’ reports of their children who “just show up” that way, but were responding to intense emotional issues in or outside the family through their expression of gender. Another obvious example of what I will call “reactive gender dysphoria” is how a young girl who has been molested may go on to create an emotional equation that if she becomes a boy, no one will bother her anymore. Children with reactive gender dysphoria do present themselves, and it is our responsibility to first get to the root of the emotional problems causing them to express their gender in the ways they do, and then to untangle those underlying psychological knots so the children can evolve into their authentic gender, based not on trauma but desire. Yet I would argue that these children represent only a tiny minority of gender-nonconforming children. And often the strongest indicator of their “minority” status is that they did not gradually become that way but changed their gender expression, at times suddenly and radically, subsequent to a trauma or emotionally distressing experience.

[much later:]

There are also children who suddenly show up with a gender issue after a trauma and with no previous history of gender bending. Here, too, we may be seeing children who are expressing other troubles through gender. For example, the three-year-old who suddenly announces that he is a girl after losing his mother to sudden death may be in a desperate emotional search to reclaim his lost mother by becoming her, rather than in a journey toward discovering his true gender self.

Ehrensaft reiterated these themes in her 2016 book The Gender Creative Child: Pathways for Nurturing and Supporting Children Who Live Outside Gender Boxes.

Now, for the sake of transparency, Ehrensaft engaged in some strange backtracking recently, co-authoring a paper with Turban and another researcher in which they claimed, “Although no evidence exists that trauma or internalized misogyny are the etiological cause of one’s trans identity, adolescents may hear these ideas in the media; addressing these unvalidated theories can prevent psychological distress related to encountering these ideas for the first time after starting gender-affirming medical interventions and open the discussion with patients to understand how they may have been affected by previous trauma or misogyny.” Maybe “strange” is an understatement, in full context — Ehrensaft herself helped seed “the media” with the idea that trauma can, at least in rare cases, lead to a trans identity, in part because of her own clinical experience. And now she’s saying that it’s important to tell kids who are on hormones that this couldn’t possibly be the case. As far as I am aware, Ehrensaft has never explained this shift.

Anyway, Ehrensaft’s original view on this remains widely held among many clinicians, and has been for decades. For example, here’s an observation from the influential youth gender clinician Domenico di Ceglie, who established the GIDS clinic, in a 1998 edited volume titled A Stranger in My Own Body: Atypical Gender Identity Development and Mental Health: “As the AGIO [atypical gender identity organization] is the result of complex interactions and influences. . . exploring in therapy its nature and targeting the developmental processes may in turn, secondarily, lead to the evolution of the organization and, therefore, to the sense of gender identity. On the other hand this may remain unaltered.” Di Ceglie is clearly saying that a cross-sex identification is sometimes the result of other factors that, when addressed, may cause that identification to shift. Sometimes, not always.

I asked Anna Hutchinson, a former GIDS clinician and current clinical psychologist, what she thought about this, and she wrote back:

There is no empirical evidence or good quality research that tests the hypotheses re: potential relationships between MH problems and GD/identity and potential relationships between treating co-occurring MH problems and the impact on GD/identity, but lots of clinical case studies that discuss these potential relationships between mental health and gender identity.

Many mental health problems impact our identity generally and severe mental health problems can have significant impact on identity formation, cohesion, etc. Then there are specific “disorders” and their potential relationship with GD/identity, like OCD for example. There’s a lot of literature that discusses “hOCD” or homosexual OCD [my link], where people obsess and ruminate about whether they are gay or not. And more recently the concept of trans-OCD has entered the literature.

In short, I don’t understand how anyone qualified to offer expert commentary on this subject could endorse a claim as strong as “There is no evidence that co-occurring mental health conditions cause a person to adopt a transgender identity, nor is there evidence to support that treatment of co-occurring mental health disorders ameliorates the core symptoms of gender dysphoria.” That’s especially true when you remember that a fair number of detransitioners, including plenty I’ve spoken or corresponded with, endorse this exact view as an explanation for their own journeys into and out of gender transition.

***

This next section of The Integrity’s Project’s report appeared in the first version posted to Yale Law School’s website, then it was deleted with no explanation, and now it has been reinserted. (The line “The transparency and expertise of our group starkly contrast with the [Cass] Review’s authors,” I should note, was present in every version.)

Let me explain: While Yale didn’t respond to my initial emailed interview request that I sent their comms folks prior to the publication of Part 1, when I emailed to ask about what appeared to be stealth edits to the document, I included Anne Alstott in my query and she did respond. On August 26 she wrote:

Thank you for reaching out with a specific question. We are glad you brought this inadvertent error to our attention. On July 11, we sent our communications people an updated draft that should have had only two changes. Both of these changes are minor: (i) the addition of one person to be thanked, and (ii) a standard statement that “This work reflects the views of individual faculty and does not represent the views of the authors’ affiliated institutions.”

Unfortunately, it seems that these changes were, by mistake, incorporated into an earlier draft of the report, which is the version now posted on the site. The use of the earlier draft was entirely unintentional. Dr. McNamara informed me that she unintentionally sent the penultimate draft. We will immediately re-post the original document in full, as intended, with only the two changes mentioned above.

After I pointed out that there were actually significant changes between the two documents (you can see all of them here), not merely minor ones as she was claiming, she followed up: “The authoritative and intended version of the white paper is the one that was posted on July 1 and remained there until our inadvertent substitution on July 11. You can obtain a copy on the wayback machine. That is the version that we will be re-posting to the website today.”

This suggests that the wrong version of the document was posted on The Integrity Project’s website for a month and a half or so without anyone noticing. And the differences between the restored version and the version McNamara filed in Boe remain unexplained. In many cases, I had to fix quotes and page numbers in this document because they referenced what was apparently an out-of-date, accidentally posted version of it.

This is a pretty good reason to be transparent when you update a document. At no point has The Integrity Project made clear that different versions of the document appeared on its website at different times, and that the wrong one was up there for a month and a half. As you’ll see, the text that follows contains specific criticisms of specific people who were part of the document, until they weren’t, until they were again — all with no explanation anywhere on Yale’s or The Integrity Project’s websites.

On the one hand, this obviously runs completely contrary to basic scientific (and, for what it’s worth, journalistic) norms. You can’t just upload different versions of the same document at different times without documenting the changes. On the other hand, The Integrity Project appears to really just be Meredithe McNamara and Anne Alstott, and they just kind of post whatever they want to Yale’s website with no substantive peer review or quality control, and then Yale Law School promotes it, so in reality there’s no oversight and they can do whatever they want. From YLS’s point of view, it seems problematic to host and promote a document that gets substantively edited at different times with no transparency.

Anyway, it’s good that this passage was reinserted, because it again demonstrates just how confused McNamara, Alstott, and their colleagues appear to be about the purpose of the Cass Review.

All of what follows was missing from the white paper for a month and a half, and is missing from the Boe version of the document:

The Review’s statements often conflict with its own recommendations

The Review’s statements and its recommendations often diverge. For a document that offers guidance on clinical care, this internal inconsistency is highly unusual. (1) Acknowledgment that certain youth may benefit from medically affirming interventions is undercut by the Review’s recommendation to limit care to a nonexistent clinical trial framework that it proposes but does not describe. Discussion of the need for an individualized assessment is eclipsed by a call for all youth to be a certain age before they may obtain guideline-recommended care. (2) Agreement with WPATH and the Endocrine Society on optimal treatment of co-occurring mental health conditions is disingenuous when, in later pages, (3) the Review speculates, without evidence, about the possibility of gender dysphoria emerging as a result of mental illness, pornography consumption, neurodiversity, social media, and peer influence. [8] [numbers added by me]

On (1), it’s unclear why McNamara and her colleagues are confused by the idea that some patients may benefit from a treatment, but because there’s a lack of solid evidence, a clinical trial is advisable. A lot of treatments might benefit patients — the whole point here is that you are supposed to amass evidence that they do before administering them widely, which certainly didn’t happen in the case of youth gender medicine. As Cass and her team write, “We do not know the ‘sweet spot’ when someone becomes settled in their sense of self, nor which people are most likely to benefit from medical transition. When making life-changing decisions, what is the correct balance between keeping options as flexible and open as possible as you move into adulthood, and responding to how you feel right now?”

As for (2), it’s quite strange that McNamara and her colleagues accuse the Cass Review of being “disingenuous” for publishing text that seems to partially align with certain aspects of the WPATH and Endocrine guidelines but that appears to deviate from them in others. This was a big enough deal to McNamara that she included it in the sworn declaration she filed in Boe v. Marshall, criticizing the Cass Review on the grounds that some of its content “conflict[s] with international standards of care, including the WPATH and Endocrine Society guidelines.” (A version of the white paper was attached to that declaration as evidence of the Cass Review’s supposed weaknesses.)

But the Cass Review sought to evaluate these and other guidelines by commissioning a systematic review of them. That review found that “Most national and regional guidance [on youth gender transition] has been influenced by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and Endocrine Society guidelines, which themselves lack developmental rigour and are linked through cosponsorship.”

Which all leaves us with this sequence:

Cass Review: We evaluated the WPATH and Endocrine Society guidelines and found that they are not rigorously constructed.

McNamara, Alstott, and their colleagues: The Cass Review conflicts with the WPATH and Endocrine Society guidelines!

To repeat something I said multiple times in Part 1, the only options here are that McNamara and her team did not read the Cass Review carefully, or they are intentionally misrepresenting it.

On (3), it’s not just McNamara and her colleagues complaining — many critics of the Cass Review have treated the document’s mentions of “mental illness, pornography consumption, neurodiversity, social media, and peer influence” as possible contributing factors to the uptick in youth referred to gender clinics as a smoking gun of the effort’s fundamental malevolence or incompetence. After all, we know that these aren’t factors, right?

Well, we don’t. Coexisting mental health problems and autism, both of which appear to be getting more common in kids referred to gender clinics, can absolutely complicate the diagnostic picture for a given young person. This is right in the WPATH Standards of Care that McNamara and her colleagues imbue with such authority:

In some cases, a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicating mental health histories (Leibowitz & de Vries, 2016)), co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics (Strang, Powers et al., 2018), and/or an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence (Ristori & Steensma, 2016).

Recall that Jack Turban said, under oath, that he remembered an instance in which a patient’s autism contributed to a misunderstanding of his gender identity, and that it took some clinical work to untangle this. I don’t understand how Turban can say this in one context, and then, in another, co-author a sentence accusing another doctor of “speculat[ing], without evidence, about the possibility of gender dysphoria emerging as a result of. . . neurodiversity[.]”

Sophisticated clinicians do understand that there can be complex interplays here, which is why these cautions found their way into the WPATH SoC 8 despite the presence and influence of an outspoken anti-gatekeeping faction within WPATH (which Emily Bazelon discussed in her New York Times Magazine article about these debates).

As for peer and cultural influence, these are obviously controversial topics, but it’s simply strange to think of any area of adolescent life where they have no impact — why would gender identity development be an exception? If there’s a good answer to this question, I haven’t heard it. (We’ll return to this a little bit later.) The theory that gender identity development cannot be influenced by peer and social relations runs contrary to the prior work of many leaders in this field, including Diane Ehresnaft, who wrote with Colt Keo-Meier that “Each child spins their own unique gender web based on three major categories of threads: nature, nurture, and culture.” One would have to twist oneself into some sort of exceptionally complicated six-dimensional pretzel to argue that the phrase “nurture and culture” does not include peer and social relations.

More importantly, McNamara and her colleagues’ theory of a complete lack of connection between social and peer relations and gender identity/dysphoria is deeply radical, and deeply out of step with everything we know about adolescent developmental psychology. It has caught on not because there is any a priori scientific merit to it, but because it is seen as a bulwark against some people’s claims that young people who say they are trans aren’t, really. It is a rather pure example of a sciencey-sounding claim that is fundamentally political. This theory just shouldn’t be taken seriously until anyone can explain how it fits into a towering pile of past work about adolescent psychology, social influence, and a bunch of other subjects. (It’s also worth remembering that the vast majority of the recent uptick in referrals to gender clinics has occurred among natal females, and adolescent girls are thought to be much more susceptible to social influence and symptom contagion than boys — see the excellent recent podcast Hysterical for an astonishing example centered on an upstate New York town.)

On pornography, the Cass Review contains a single section of about 230 words that cites some general research on its impact (none that directly ties it to GD, to be clear), as well as an article in which the psychiatrist Dr. Karin Nadrowski argues that for natal females with gender concerns, clinicians should explore whether their exposure to pornography is a potential contributing factor to their feelings about gender. Her theory is that the disproportionate uptick in natal female adolescents expressing feelings of gender dysphoria could come partly from exposure to misogynistic forms of pornography, which contribute to their desire to not grow up to be women.

This is, as McNamara and her colleagues note, speculation, but there’s nothing wrong with that. The Cass Review (meaning the summary document, not the systematic reviews) both sums up the available evidence on youth gender dysphoria and discusses broader questions about the phenomenon. It’s unclear why we should dismiss pornography out of hand as a potential, contributing factor in some cases of gender dysphoria, or why it should be considered offensive or scientifically wrongheaded to ask this question given how little we know about the nature of gender identity development in young people.

In a footnote, McNamara and her co-writers express concerns about Nadrowski’s article, writing that “The Review cites a commentary supposing that pornography consumption drives youth to be transgender. This article was written by an individual from an organization with an ideological rather than scientifically informed perspective on gender identity. That organization, Therapy First, advocates for a singular approach to everyone who expresses gender diversity and pathologizes non-cisgender identity.” [8]

The article doesn’t “suppose” this theory is true — it raises it as a possibility. There’s a large and important difference. If a scientific researcher writes “This is true” without providing evidence, that’s clearly out of bounds. If they write “I think this thing might be true — here’s how we can investigate it and study it,” that’s completely within the normal bounds of scientific inquiry. That’s what Nadrowski did. Maybe she is correct that exposure to porn can influence youth gender identity development and maybe she isn’t, but she’s just posing a theory and suggesting it should be part of the assessment process for clinicians working with gender-questioning youth.

What’s particularly odd about McNamara and her colleagues’ reaction to this is that clearly, if a cisgender (say) 14-year-old girl was experiencing psychological distress related to her sexuality, body image, anxiety, or anything else that can be considered “gender”-related, and was also consuming a lot of pornography, that’s something her therapist would likely want to explore. Sometimes it feels like there’s this special cordoned-off Youth Gender Zone in which the usual standards of therapy and differential diagnosis don’t apply.

Therapy First, as the name implies, advocates for therapy as a first-line treatment for youth gender dysphoria. It’s noteworthy that McNamara and her colleagues describe it as “an organization with an ideological rather than scientifically informed perspective on gender identity,” and one with a “singular approach to everyone who expresses gender diversity.”

Throughout their white paper, McNamara and her colleagues present themselves as the careful, reasonable scientists, whereas anyone who has any qualms about youth gender medicine is deemed an activist who is un- or underqualified to participate in this debate. But of course Johanna Olson-Kennedy and Jack Turban’s views that trans kids know who they are and should more or less be allowed to take blockers and hormones if they want them is in no sense objective or scientific — it’s ideological as well. And whatever one thinks of Therapy First, Olson-Kennedy and Turban themselves seem to have just as “singular” a view of how to deal with gender dysphoric kids: If they want medicine, they should get it.

In short, the only reason McNamara and her colleagues treat some beliefs as too ideological and others as sufficiently scientific is. . . well, ideology.

***

McNamara et al. note, accurately, that treatment guidelines generally include four components: evidence for a treatment’s efficacy, the benefits and harms of treatment or nontreatment, patients’ values and preferences, and (not really relevant to the present discussion) resource considerations.

McNamara and her colleagues argue that the Cass Review neglects the “values and preferences” part of the equation:

The Review does engage with transgender young people, but it often makes recommendations that conflict with their expressed values and preferences. The prevailing theme of the focus groups with transgender youth is that they want improved access to appropriate gender-affirming medical services from clinicians who have appropriate training and experience. They want their needs and concerns taken seriously. The Review completely disregards the expressed values and preferences of transgender youth in its most emphatic recommendation, which is to limit care to research settings that do not yet exist. [10–11]

First of all, the Cass Review doesn’t recommend an all-out ban on youth gender medicine outside of research settings: “The option to provide masculinising/feminising hormones from the age of 16 is available, but the Review would recommend an extremely cautious clinical approach and a strong clinical rationale for providing hormones before the age of 18.” As for puberty blockers, in a follow-up FAQ the Cass team wrote that “Ahead of publication of the final report NHS England took the decision to stop the routine use of puberty blockers for gender incongruence / gender dysphoria in children.” This decision was influenced by the Cass Review, but also by the pre-Cass NICE evidence reviews, which found paltry evidence for blockers and hormones in youth transition contexts.

In any case, the patient values and preferences component of developing clinical practice guidelines is complicated, because it is more subjective than the somewhat mechanical process of, say, checking whether a given study has an appropriate comparator group (not that there isn’t some subjectivity to evaluating study quality as well). That’s doubly true with adolescents, whose preferences are important to hear out, but are not generally taken as seriously as adults’. (I don’t mean that in a derogatory way — I mean that in both the U.S. and the UK, they are legally granted less decision-making capacity.)

In light of all this, the claim that the Cass Review “completely disregard[ed] the expressed values and preferences of transgender youth” feels like an overstatement and an oversimplification. There’s no guideline anywhere that says that if a patient wants access to a treatment, they are entitled to it, evidentiary questions be damned. There is no objectively correct method for weighing these different factors, and saying “no” to a patient group, or telling them they have to wait or undergo more assessment than they like, can be a totally defensible choice, especially in the case of minors.

***

Another common tactic of McNamara and her colleagues is to highlight a possible objection to the Cass Review or to claims about the evidence base for youth gender medicine, but then to provide no evidence that the objection in question is remotely applicable to this particular controversy.

For example, in a subheadline, McNamara and her colleagues write “The Review fails to recognize the nuances of evidence quality measures” (emphasis in the original), and they then continue:

With more research, the quality of evidence in many fields of medicine does not neccessarily [sic] improve, as the study designs needed to detect smaller and smaller effects become infeasible. Thus, many areas of medicine may have inherent, real-world upper limits on quality of evidence—and that level of quality rarely accords with the theoretical ideal described by evidence-grading methodologies. [11]

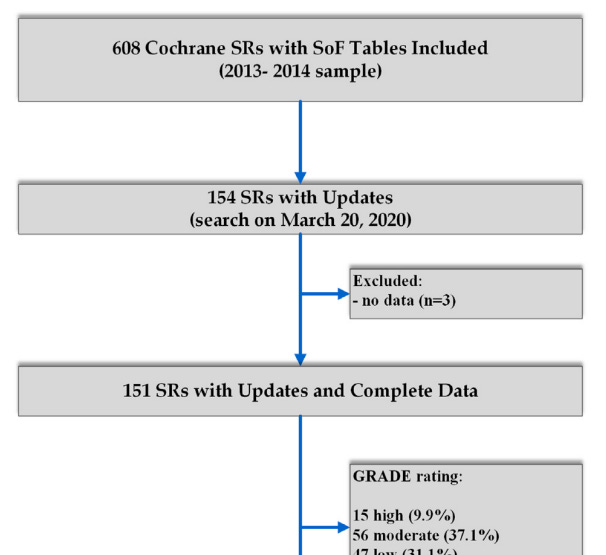

There’s a citation here to this 2020 study, in which researchers examined updates to Cochrane Systematic Reviews — a gold-standard source of medical evidence — to see if they resulted in a better ratings of the evidence quality. The authors of that study found that no, there was no consistent improvement (or worsening) of evidence quality between an initial systematic review and its update.

This has very little to do with the matter at hand. To see why, it’s important to note that the study only included Cochrane Reviews where the team published a so-called Summary of Findings:

Sometimes, there’s so little evidence on a given question that the team doing the review can’t issue a summary of findings. Take, for example, the one Cochrane Review I’m aware of that is anywhere in the ballpark of youth gender medicine: this one about hormones for adult transgender women. The authors wrote: “We found insufficient evidence to determine the efficacy or safety of hormonal treatment approaches for transgender women in transition. This lack of studies shows a gap between current clinical practice and clinical research.” And under Summary of Findings they wrote, “Following standard Cochrane methodology, had we identified any included studies, we would have created a ‘Summary of findings’ table for all three primary outcomes,” as well as GRADE evidence assessments. But because there was so little evidence, they couldn’t do any of this. And adult transgender care is widely believed to have better evidence underpinning it than its youth counterpart.

So yes, it may be true that updating the available evidence for a given medical question covered by a Cochrane Review doesn’t, on average, lead to an improvement in evidence quality, but in this case, youth gender medicine, we’re talking about an area that is so weak that there’s effectively no quality evidence at all — meaning the last thing we should worry about is that we’ve hit some sort of ceiling and it’s unreasonable to ask for better evidence. For McNamara and her team to say “many areas of medicine may have inherent, real-world upper limits on quality of evidence” in this context is like if someone asked me to shoot hoops and I said I can’t, because there’s a risk I’ll dunk the ball so hard I’ll destroy the rim. Theoretically, someone could dunk a ball so hard it destroys a rim, but there is zero risk of that happening when I am the person shooting hoops, because the average chubby toddler can outleap me.

“They are throwing anything at the wall to see what sticks” is a cliché, but it’s simply the best description of what’s going on here. Or, to switch clichés, McNamara and her colleagues are flooding the zone with claims about the Cass Review, no matter how factually challenged or irrelevant. The only goal seems to be tarring the Review so that it is taken less seriously.

***

Relatedly, McNamara and her colleagues write:

The Review’s calls for “high-quality” evidence in the care of transgender youth cannot be separated from the fact that evidence deemed high-quality by systems like GRADE most often comes from RCTs. In any area of medicine, the presence or absence of “high-quality evidence” alone should not be used to decide whether to offer a treatment that has been shown to be beneficial, and care in any area of medicine should not be stopped while awaiting specific study designs. [12]

This is extremely odd. The University of York systematic reviews didn’t use GRADE. Instead, they used significantly more lenient evidence grading systems that did not hold the studies under examination to the high standard of an RCT. In the Cass Review and the SRs, “high-quality” is genuinely used either colloquially or in reference to these gentler grading systems.

In fact, Gordon Guyatt flagged this as a possible problem with the Cass Review. “There are, as I understand it, appreciable risk of bias problems in the observational studies that are in the literature,” he explained. “But let’s say those observational studies were done well. You could say, oh, observational studies done well. Now we have ‘high quality evidence,’ we have high certainty evidence — well, except the fact that they’re observational studies means you don’t have high certainty evidence. That’s where it could play out as very problematic.” In other words, even well-done observational studies simply can’t tell us as much as experimental ones, so if you’re using a grading system that is gentler on observational studies, you could end up with an inflated assessment of the body of research. Most of the studies examined by the York University SR team were rated “moderate” or “low” quality, but because under GRADE a study starts at “low” certainty if it is observational, explained Guyatt in a follow-up email, “all this evidence would be low or very low certainty (likely very low)” under GRADE. So for all McNamara and her colleagues’ concerns that Cass and her SR authors were unduly harsh on the evidence base, the use of a non-GRADE instrument is much more likely to have had the opposite effect, casting the evidence in a rosier light than is warranted by normal medical-evidence standards.

McNamara and her colleagues also engage in rather egregious question-begging by referencing “a treatment has been shown to be beneficial,” when the whole point of the systematic reviews is to establish whether or not youth gender medicine. . . has been shown to be beneficial. And again they simply conjure a nonexistent circumstance: What if youth gender medicine were banned solely because we didn’t have high-quality RCTs on it? That isn’t remotely close to what has happened.

***

McNamara and her colleagues then explain the difficulties of running youth gender medicine RCTs. This is, in fact, a challenging problem, but in explaining why McNamara and her colleagues demonstrate significant confusion.

For example, they argue that one of the problems with running RCTs in youth gender medicine settings is

Coercion: Coercion occurs when research participation is one of the only ways to obtain a much-needed treatment. An RCT model to assess whether to give medically affirming interventions to youth with gender dysphoria may appeal to those who cannot obtain affirming interventions another way. Per international regulations on medical and scientific ethics, coercion, even when unintended, must be avoided in study design. Restricting all care to a research setting, as recent UK rules have done based on the Review, is coercive and unethical.

But researchers constantly run RCTs providing potential treatments to those who might not otherwise be able to access them. Haven’t McNamara and her colleagues heard of the coronavirus vaccines?

Setting aside the undeniable complexities of this particular context, you conduct an RCT to try to determine if a treatment works. If that’s as yet unknown, there are generally no ethical problems in withholding treatment. “The systematic reviews establish beyond a doubt that we do not know if these interventions offer health benefit,” said Moti Gorin, a Colorado State bioethicist who researches and has published articles about youth gender medicine, in an email. “This establishes we are in a state of genuine uncertainty. This means an RCT would not violate equipoise. [My link.] Therefore, no one is deprived of a known benefit. Therefore, making access, or a randomized chance at access, to the intervention conditional on participation in a trial would not be unethical.”

Further exemplifying McNamara et al.’s confusion about this whole subject, the footnote on the “international regulations” claim points to the Declaration of Helsinki, which simply doesn’t say anything like what they claim it does. But part of flooding the zone with claims is flooding the zone with references to other documentation, because who has time to read all that? For every minute McNamara and her colleagues spent writing this document, it probably takes five minutes to critique it.

***

McNamara and her colleagues claim that critics of youth gender medicine are holding it to an exceptional and unfair standard:

The Review expresses an appropriate desire to see longer, larger studies on the impacts of gender-affirming medical treatment, and this aligns with leading organizations’ views. The Review’s desire to see only high-quality evidence dominate this field, however, is not realistic or appropriate because no other area of pediatrics is held to this standard.

. . .

In an interview, Dr. Cass said, “I can’t think of any other situation where we give life-altering treatments and don’t have enough understanding about what’s happening to those young people in adulthood.” In fact, due to the realities of the research dynamics described above, many pediatric medical treatments are based on limited research. [13–14]

Setting aside the fact that, again, no one involved in the Cass Review believes that only high-quality evidence should inform decision-making on youth gender medicine, and the systematic reviewers used a forgiving grading system, this is misleading.

It is definitely true that there are areas of medicine, including pediatrics, that rely on less-than-stellar evidence bases. But whether or not experts view that as acceptable depends a great deal on high-stakes matters of context that McNamara and her team ignore entirely.

Let’s use an extreme hypothetical to illustrate the point. Imagine that the pediatric establishment gets it into its collective head that increasing the water consumption of kids 5–10 years old by two cups a day brings with it health and developmental benefits. Let’s also say that a systematic review of the research on this question turns up only “low-quality” evidence to support this practice, meaning we just don’t know. In this case, a reasonable pediatrician might nonetheless recommend that parents give their kids two extra cups of water a day. That’s because in most cases, the risks of doing so are likely quite low. In a case like this, the fact that the evidence is low-quality probably shouldn’t be considered a decisive factor against the intervention in question.

The same general principle also applies to sadder situations involving, say, pediatric terminal cancer. If a kid (or adult) is very likely to die due to a condition they have, it doesn’t make sense to withhold treatment on the basis that there is a lack of evidence for it. In a situation like this, the result of nontreatment is death. The result of treatment is. . . well, probably also death, but there’s an obvious moral case for allowing a child to access treatment in this situation, even if there’s only low-quality evidence for it. There’s just far less potential downside relative to nontreatment, except in certain outlier situations where the treatment also brings terrible side effects.

But this reasoning does not translate well to puberty blockers and hormones in a youth gender medicine context. These are major interventions for a little-understood condition (gender dysphoria) that sometimes seems to go away on its own — more on that in Part 3 — and the potential harms, including myriad unanswered questions about cognitive development, sexual function, and fertility, are quite well-established, even if researchers are in some cases unsure how severe those risks are. Plus, if all goes to plan, a teen who goes on hormones will take them for many years. This is exactly the sort of situation where you want to be extra careful, and where the quality of the evidence does matter a great deal. This is nothing like “an extra two glasses of water” or an experimental treatment for terminal cancer.

To see just how much the McNamara et al. team have to stretch their logic to argue that Cass is imposing unfairly high standards on youth gender medicine, consider the specific examples they raise: the choice of “breathing tube or a non-invasive measure” for infants with respiratory problems; the choice of breast milk versus formula for premature infants whose mothers can’t produce milk; and how much intravenous fluid to provide to an infant with sepsis. [13–14]

In all of these situations, doctors have a very clear understanding of exactly what they’re treating and how to treat it. If an infant isn’t getting sufficient oxygen, a breathing tube provides it to them. No one is going to say “Don’t give that child a breathing tube, because we don’t have high-quality evidence it beats every other alternative,” and then let the child suffocate.

Is it important to establish, conclusively, which intervention is best and safest in these cases? Of course it is. But these are such different scenarios that the comparison shatters if you so much as look at it for too long. In youth gender medicine, doctors often don’t even agree on exactly what they’re treating, how to treat it, how to measure whether it works (one of the “best”-regarded tools for measuring gender dysphoria has a fatal flaw — scroll down here to “The following hypothetical” if you’re curious what I’m talking about), or how likely the condition is to go away without medical intervention. Administering medicine with weak evidence underlying it is quite different in a situation like this than it is in a situation where everyone agrees on what the kid needs (oxygen or milk or fluids), but where there’s disagreement on the best way to fulfill the need in question.

***

On that same subject, McNamara and her colleagues write:

The evidence that helps answer these and other questions is rarely “high quality” (as the term is used in GRADE). And yet, clinical outcomes are good and improving: more children leave intensive care units better off than ever before. Most aspects of neonatal and pediatric critical care became accepted clinical practice because of their immediate and short-term benefits, without following patients into adulthood. Even now, the degree to which children discharged from intensive care achieve full neuro-developmental and functional recovery is not well-known and this is a new, active area of research in the critical care world. The quest for longer and more data is never-ending, but when the answers are only partially available, patients cannot wait for care. [14–15]

McNamara and her team are again gesturing toward unrelated facets of pediatric medicine and medical research that don’t apply here. Yes, doctors might use one particular apparatus because they think it is the best thing going at the moment for keeping an infant’s oxygen levels up, even if they lack access to 20-year studies on this subject. But this is a short-term intervention to solve a very concrete, well-understood problem. What does a situation like that have to do with a treatment that has massive effects on an adolescent’s developing body, and whose long-term effects remain unknown? What does any of this have to do with emergency interventions in NICUs?

The simplest answer to these questions is, again, that McNamara and her colleagues are simply launching a blitzkrieg of claims against the Cass Review, favoring quantity over quality.

***

More:

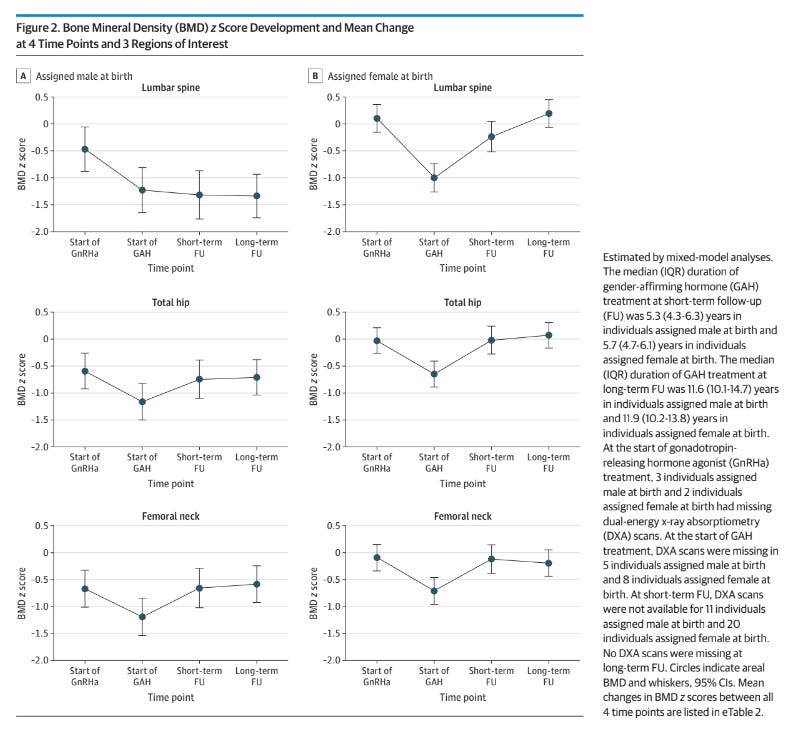

In youth gender care, we have evidence that these medications effectively treat gender dysphoria, that young people continue these medications into adulthood, that their satisfaction with gender-affirming medical treatments is high, that their bone density recovers after puberty-pausing medications, and that their transgender identities persist. [14–15]

This is very irresponsible language, especially given the severity of the conflict of interest here — as I noted in Part 1, several of the authors of this article work in gender clinics. They profit directly from providing blockers, hormones, or surgery to kids. Some of them get paid hundreds of dollars an hour as expert witnesses for the legal teams seeking to secure or regain access to youth gender medicine in states where it has been banned or is under threat. And here, in two sentences, they make not one, not two, but five statements that are absolutely unproven by normal research standards. And they do so in an exceptionally slippery way, by saying “we have evidence” to support these claims. “We have evidence to support X” means bupkes in the absence of any information about the quality of that evidence. That’s one of the major points of the Cass Review, and one that seems to consistently elude the authors of this white paper.

The Cass Review SRs themselves determined we are lacking in evidence when it comes to the claims about gender dysphoria reduction and bone density recovery. The remaining three claims, that young people continue these medicines into adulthood, that they are very satisfied with their treatment, and that their transgender identities persist into adulthood, are not directly addressed by the Cass Review but are hotly contested, with different studies pointing in different directions.

Some of the studies showing high rates of continuation and/or satisfaction come from the Dutch clinic. People should be very careful about extrapolating from these studies. These cohorts tended to be carefully selected on the basis of having had gender dysphoria since childhood and a lack of other mental-health comorbidities. It is reckless to assume that these findings can be extrapolated to kids who are less carefully screened, and kids in the United States are, almost always, less carefully screened than the early members of the Dutch cohort were. Plus, far more of them come out as trans in adolescence, and we know even less about the developmental trajectory of that cohort.

If we’re going to cherry-pick one-off studies or collections of studies like McNamara and her colleagues do, there are plenty that call the above claims into question. Two of them are lead-authored by Johanna Olson-Kennedy, a co-author of this white paper. One of them concerned 101 kids who were given hormones at her clinic. Her team could collect data for only 59 of them a year later, meaning about 40% were lost to follow-up. In another Olson-Kennedy study, she and her team followed up with young people who had gotten double mastectomies between ages 13 and 25. In that study, 26% of the cohort was lost to follow-up, despite the fact that the vast majority of contact attempts were made two years or less after surgery. Olson-Kennedy and her team also used no validated measures to gauge the patients’ well-being. So between these missing kids and missing measures, how can Olson-Kennedy co-author the above sentence, which makes it sound like researchers are doing a great job evaluating the effects of youth gender medicine and tracking the kids who receive it into adulthood?

I don’t want to single her out, because as any reader of this newsletter knows, the extant literature on youth gender medicine is rife with these sorts of problems. That’s why evidence reviews have so consistently come to the same conclusion that the York reviewers did. The answer to almost every question about the long-term trajectories of teens and young adults who receive these treatments is “We don’t know yet.”

That’s why everyone who co-authored the above sentence should understand how irresponsibly overheated it is.

***

McNamara and her team level another accusation of unfairness at the Cass Review:

The Review has outsized and vague concerns about long-term data

It is difficult to discern validity in the Review’s preoccupation with long-term data in youth gender care. It claims there is no long-term data, but does not define what it considers “long-term” to mean; it does not describe what long-term outcomes would satisfy its concerns, and does not consider evidence that has followed patients for over a decade. [15–16]

The first part of this excerpt is silly and disingenuous linguistic nitpicking. Researchers use the term long-term in a general manner all the time. Olson-Kennedy lead-authored a study protocol which noted that “there is minimal available data examining the long-term physiologic and metabolic consequences of gender-affirming hormone treatment in youth,” without describing exactly what she meant.

In one context, the Cass Review does go into a significant amount of detail explaining what it means, anyway — the fact that after kids age out of GIDS and into the adult NHS gender identity service, they are just about always lost to follow-up. The Cass team attempted to improve this situation but ran into a roadblock:

A strand of research commissioned by the Review was a quantitative data linkage study. The aim of this study was to fill some of the gaps in follow-up data for the approximately 9,000 young people who have been through GIDS. This would help to develop a stronger evidence base about the types of support and interventions received and longer-term outcomes. This required cooperation of GIDS and the NHS adult gender services. In January 2024, the Review received a letter from NHS England stating that, despite efforts to encourage the participation of the NHS gender clinics, the necessary cooperation had not been forthcoming. [paragraph numbers omitted]

As for McNamara and her colleagues’ claim that the Cass Review “does not consider evidence that has followed patients for over a decade,” here they point to a footnote which reads: