Why Everyone Should Know The Story Of Lucia de Berk

A witch hunt mixed with statistical incompetence? Sign me up!

What incidents from history do you think all decently educated people should know about? Not the big ones, the most important wars and revolutions and innovations, but the smaller, less well-known ones — the stories that aren’t that big a deal in the grand scheme of things, but which are surprisingly rich when you dig into them?

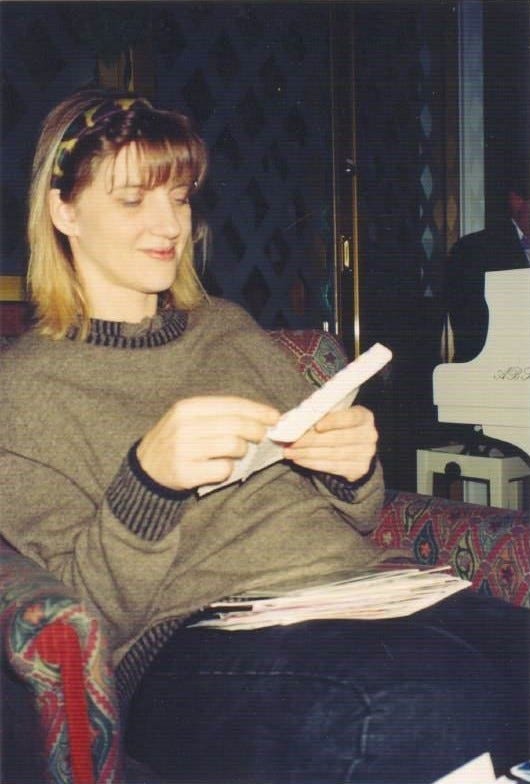

One strong choice, for me at least, is the story of Lucia de Berk, the Dutch nurse who was imprisoned for killing four of her patients.

It started on September 4, 2001. De Berk was working a shift at Juliana Children’s Hospital in The Hague. An infant named Amber “had struggled since birth with a complicated condition involving anomalies of the heart, brain, lungs, and intestine,” writes the mother-and-daughter author team Leila Schneps and Coralie Colmez in the 2013 book Math on Trial: How Numbers Get Used and Abused in the Courtroom:

At around 11:00 p.m. on September 3, Lucia decided to connect Amber to a monitor to keep close track of her heart rate and breathing difficulties. She also called for doctors to come and examine the baby, who seemed to be growing steadily worse. Amber was wheeled to the examining room, and two pediatricians examined her; the time of the examination was recorded as 1:00 a.m. on September 4. They put her on a drip and diagnosed her with enteritis, an inflammation of the small intestine, but they did not judge the child to be dangerously ill. After the examination, they sent Amber back to her room, where she was reconnected to her monitor by finger cuff.

At 2:46 a.m., little Amber went into crisis. To the horror of the two nurses in the room, the baby’s breathing frequency dropped suddenly and drastically, followed by a slowing of her heartbeat. Her face turned gray. They called for a doctor at once, and he immediately summoned the resuscitation team, but it was impossible to save the dying child. They spent forty-five minutes trying to revive her, but she was declared dead at 3:35 a.m. Her heart had actually stopped beating sometime earlier.

The doctors familiar with Amber’s situation did not find her death suspicious; they knew how ill she had been. But the doctors who were present that night were not the ones involved in her regular treatment. Nevertheless, they signed a declaration of natural death.

The trouble for de Berk began the next day, when one of de Berk’s fellow nurses approached her superior to express her concerns: de Berk had been present at five resuscitations during just two years at the hospital.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Singal-Minded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.