Where's the Campus-Free-Speech Crisis?

Plus: A stunningly bold visual gag involving Nancy Pelosi

(It was extremely kind of Speaker Pelosi to offer this unsolicited shout-out during last night’s State of the Union address, and it helps explain the 3.2 million new subscribers I picked up overnight.)

I had planned on writing something about the State of the Union in this intro — just a few cutting sentences — but man do I not have it in me. This is a tired and shambling and besieged presidency and what can you even say at this point? You subscribed to my newsletter for blazingly original insights about why people are jerks on Twitter, anyway — not for political commentary

A Paragraph That Made Me Happy...

All non-football fans need to know to understand the below paragraph from this ESPN article on the Cleveland Browns is that Teddy Bridgewater had a couple very promising years as a young quarterback before his career was derailed by injuries (he has barely played since the 2015-2016 season), while the one-time super-hotshot college quarterback Johnny Manziel flamed out of the NFL almost immediately because he simply wasn’t good at professional football, and because he apparently had unresolved substance-abuse and mental-health issues as well. Here’s a glimpse at the organizational “process” by which then-Cleveland assistant general manager Ray Farmer and co-owner Jimmy Haslam* eventually decided to make the in-retrospect extremely wrong decision to draft Manziel rather than Bridgewater:

With the second first-round pick, Farmer was targeting Oregon State receiver Brandin Cooks. But then Manziel started to slide and Haslam wanted Manziel. Some of the football guys in the room wanted to wait and pick Bridgewater in the second round. But the team had soured on Bridgewater after his interview dinner and workout with team brass; something about Bridgewater's handshake rubbed Haslam the wrong way, he told team executives.

As someone who writes and thinks a lot about human biases and decision-making failures, a story like this is a big, juicy (tofu) steak to me. Who cares about Bridgewater’s handshake? Or whether he charmed you at dinner? Maybe he was tired! More people — especially rich and powerful ones, like for example those who own football teams — should understand just how terrible humans can be at interpreting certain types of ambiguous information, given that that information will inevitably be filtered through myriad biases.

(*Speaking of human frailty! This paragraph initially mentioned Dee Haslam, Jimmy’s wife and co-owner, rather than Jimmy — the guy who actually made the handshake remark. I also linked to an article aggregating and reacting to the ESPN piece rather than the ESPN piece itself. Both errors have been fixed.)

...and a Paragraph That Made Me Sad

Via Wesley Yang, here’s a snippet from a 2014 London Review of Books essay by Paul Kingsnorth in which he discusses two then-recently-released books about climate change:

It is clear now that stopping climate change is impossible: what is still worth fighting for is some control over how bad it will get. Neither [authors Naomi] Klein nor [George] Marshall can convincingly tell us how we should get from where we are to where we need to be in the time available; but then, neither can anyone else. Reading these books back to back, I’m inclined to side with Daniel Kahneman, whom Marshall spoke to in a noisily oblivious New York café. Kahneman won a Nobel Prize for his work on the psychology of human decision-making, which may be why he’s so gloomy. ‘This is not what you might want to hear,’ he says, but ‘no amount of psychological awareness will overcome people’s reluctance to lower their standard of living. So that’s my bottom line: there is not much hope. I’m thoroughly pessimistic. I’m sorry.’

Name one reason why, in 2019, we should be less pessimistic. I’m waiting. And I don’t think a miracle technological fix is in the offing either, at least not anytime soon.

So Like is There Actually a Campus Free-Speech Crisis or What?

I’ve long expressed conflicted views on the many facets of the campus culture wars. I think there’s very little to the “trigger warning” panic that has been wielded for years, mostly by conservatives, as a culture-war cudgel, but I also think microaggression trainings — which are very much also a culture-war cudgel — are based on really shaky evidence and, viewed from certain angles, may be actively harmful to students exposed to them. I remain unconvinced by arguments that we now live in a “victimhood culture” (though I have to admit I’ve wavered on that subject a little bit since I wrote the linked-to essay in 2015), but I think we should keep an eye out for, and try to push back strongly against, claims that mere offensive or controversial or conservative speech does lasting harm to vulnerable students. I also think that those on the left who brush aside the significance of silly, sometimes hysterical tropes like Only reactionaries care about ‘free speech’! and Speech I disagree with is traumatizing! tend to downplay the very real possibility that those tropes will come back to bite them and causes they care about, like pro-Palestinian activism, in the butt — or be exploited by slimy right-wing actors. But at the same time, there’s just never been particularly strong evidence modern-day college students’ beliefs on free speech differ all that much from the rest of the public’s. And so on — look at me with all this loathsome nuance.

It’s no surprise, in light of the writing I’ve done on these sorts of issues, that a new report on campus-free-speech issues recently published by the Niskanen Center caught my eye. In “The ‘Campus Free Speech Crisis’ Ended Last Year,” Jeffrey Sachs, a lecturer at Acadia University, argues, well, that. As the scare quotes indicate, Sachs doesn’t seem completely on board with the idea that there ever was a full-blown campus-free-speech crisis to begin with. But in his article, he runs down certain recent improvements on this front and argues, compellingly, that whatever was going on in recent years appears to have dissipated, at least for now.

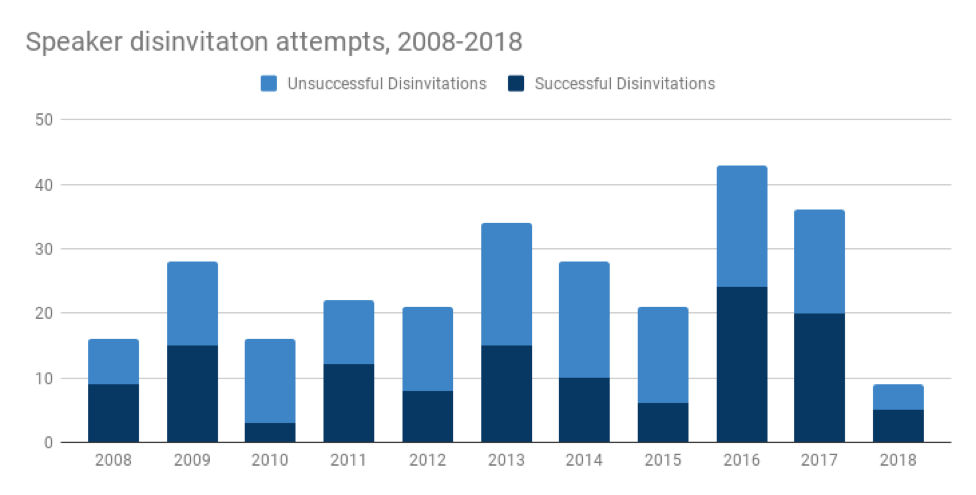

Here’s one of several important charts embedded in the article, and below that the meat of Sachs’ argument:

This past year, the number of disinvitation attempts fell to nine. That number is likely to increase a bit as investigations into several potential cases are concluded, but the final tally will almost certainly represent an enormous drop from previous years. And of those nine attempted disinvitations, only five were successful, with one speaker re-invited back to campus the following month. While a small number of protests early in the year turned violent, none came close to matching the chaos seen at Berkeley or Columbia in 2017. Even speakers like Ann Coulter and Dinesh D’Souza, who in the past have both generated a heated campus response, were able to speak in 2018 without incident.

But it wasn’t just disinvitations that dropped in 2018. So did the number of professors terminated for political speech. In 2016, 14 faculty members were either fired, demoted, or forced to resign for politically controversial speech, a significant increase over previous years. In 2017, that number climbed to 28. But this past year, just eight faculty were terminated or demoted – four due to criticism from their political left, three who were criticized from their political right, and one whose critics can’t be characterized in left/right terms. In general, university administrators proved much more willing to defend their controversial faculty, even in the face of public outrage.

On these and other issues, like the number of colleges with hate-speech codes (which “fell to historic lows”), the news is almost entirely positive for us free-speech junkies. Sachs runs through a bunch of potential explanations and counterpoints in a really comprehensive, engaging way that’s difficult to sum up concisely, but which is definitely worth checking out. He concludes with a pretty credible explanation (or at least a partial one) for what appears, in retrospect, to have been but a brief paroxysm of free-speech-unfriendly campus activism:

Why the new culture of tolerance? Some of it, I suspect, is due to the efforts of groups like PEN America, FIRE, and Heterodox Academy, which have been working tirelessly all year to promote dialogue and protect free speech. Fear of litigation is also likely to have made a difference. But I suspect the broader national political climate may be an even more important factor. Few observers truly appreciate how deeply the culture on campus is shaped by events taking place off it, which is why I suspect there is too little recognition that many of the events of 2016 and 2017, when concern about the “Free Speech Crisis” was at its height, were tied to the presidential election.

Trump’s campaign and victory generated enormous consternation among many students and faculty, leading some to embrace confrontational forms of activism. In this, they were no different from activists off campus. But as that initial surge of panic has receded, so has the combative sense of urgency and alarm that drove campus activists when it was vivid and fresh. In other words, it is probably not that students are suddenly being won over by Mill’s On Liberty.

That makes sense to me. I doubt any short-term changes to the free-speech climates on American college campuses are due to meaningful ideological shifts among students rather than a million other more important factors, many of them, as Sachs suggests, external. If you’re a campus activist, the world, and the level of urgency you would apply to a task like trying to prevent a conservative pundit from speaking at your school, probably looked a lot different in January of 2017 than in January 2019. This stuff tends to have a cyclical nature to it.

Questions? Comments? Invitations for me to come speak at your colleges followed by immediate disinvitations, followed in turn by immediate re-invitations and dis-re-invitations? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal.