This Book About Knowing Our Cognitive Limits Is Fantastic And I Have Copies To Give Away

And if you don't win, you should buy a copy

Newsletters You Missed If You Aren’t A Paid Subscriber, With Brief Summaries

Belief, Identity, Bias, And The Osmium Parable — Imagine a cult built entirely around a fundamentalist belief in the atomic weight of osmium, and what happens to its members when that belief is challenged

This Salman Rushdie Story Is So Good I Want To Marry It — Imagine a film about Salman Rushdie being an evil criminal mastermind with a hideout in the Philippines who tortures and murders the devout Muslims seeking to bring him to justice (cuz it’s real)

On White Progressive Solipsism — Imagine if there are forces in the world more important than the pop culture middle-class suburban white kids are exposed to

I Am Becoming Addicted To Getting Angry At Terrible Anti-Free-Speech Arguments — Imagine if major newspapers kept publishing undercooked articles claiming we need to “do something” about free speech

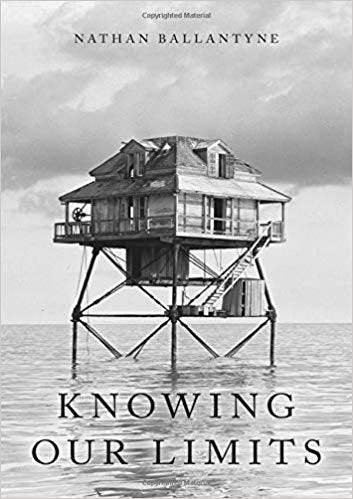

Book Giveaway: Knowing Our Limits By Nathan Ballantyne

On Friday night I was at a Halloween party, and I randomly ended up talking to someone with a background in epistemology, the philosophical study of knowledge. This person also does some freelance writing, and she told me she’d seen my very positive tweets about Knowing Our Limits (Amazon), a new book out from Oxford University Press by the Fordham University philosopher Nathan Ballantyne.

She read it, also thought it was great, and wanted to write about it for some outlet, but she was having trouble formulating a pitch because when you actually explain what’s in the book it sounds slightly, well, obvious. I realized that she had nailed my own problems trying to figure out how to write about this book, and why it’s not easy to summarize.

But I’ll try. In Knowing Our Limits, Ballantyne explains that one area of academic epistemology has become very enamored with philosophical problems and puzzles that aren’t particularly relevant to non-epistemologists. If you get a bunch of epistemologists in a room and ask a question like “What is knowledge?,” things quickly get exceptionally complicated, and there is a deep, often very technical literature surrounding this and other questions. (For a good layperson-friendly introduction to one particular epistemological rabbithole, definitely check out the episode of the excellent podcast “Very Bad Wizards” centered on so-called “Gettier cases.”)

It’s a regrettable state of affairs that this has become arguably the dominant focus of epistemology, argues Ballantyne, because it’s a field that could offer so much to normal people out in the real world. Everyone is faced with complicated questions about what to believe and why, after all, and we live in perhaps the most confusing-ever age on that front, thanks to various pernicious influences like hyperpartisan media and Facebook fraudsters and my own Twitter feed. Plus, a real-world-tethered epistemology has more cross-disciplinary potential than ever before, given advances in fields ranging from psychology to neuroscience to sociology. (Ballantyne himself has focused on cross-disciplinary work with psychologists.)

To be clear, Ballantyne doesn’t want epistemology to abandon all of the more esoteric stuff. Much of it is interesting and philosophically important in its own right, he argues, and you also never know when today’s technical side-question becomes tomorrow’s launchpad for discoveries of practical importance. But Ballantyne does call for a refocus on and a reinvigoration of “regulative epistemology” — that is, a flavor of epistemology that can offer everyday people some guidance with regard to their own beliefs and whether they are justified.

He then takes the reader on a tour of what such an epistemic ‘method’ would, or should, look like. Sometimes, it does get a bit complicated. This is definitely a book that you will get the most out of if you have some experience reading or studying philosophy. You should feel comfortable encountering and mentally playing around with a claim like “If a group of methodologically-friendly counterfactual interlocutors had scrutinized my best arguments for some proposition p and then shared their thoughts, I very likely would have defeaters for believing p.” But Ballantyne is such a good, brisk, clear writer that at no point did I feel at all trapped in the weeds, despite the fact that, while I did major in philosophy, I was a mediocre student at best and got my degree an estimated 200 years ago.

I found this to be a deeply, deeply absorbing book that, for lack of a better word, refreshed me: It made me realize that despite the constant drumbeat of nonsense we are all exposed to on a daily basis, there really are ways to sit and reflect and come to terms with one’s own epistemic frailty in a rigorous and systematic way. It doesn’t just have to be a motto that is oft-repeated but rarely followed — Yes, everyone’s biased, including me — but can, if you really work at it, become a way of cognitive life. Personally, I know I’m not even close to there yet, but I’ve never read a book that offers as much useful practical guidance about this journey as Ballantyne’s does — all while being extremely enjoyable. (Again, the writing is really, really good.)

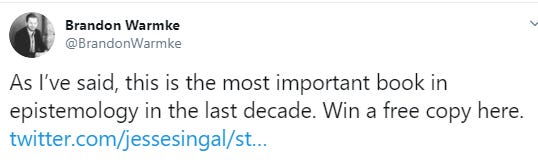

Anyway, I’m going to leave it at that. I recommend this book very, very highly. If you don’t believe me, here are a couple of glowing words from actual, real-life philosophers, like this tweet from Brandon Warmke, a philosopher at Bowling Green State University...

...or this longer blurb from the British philosopher Quassim Cassam:

The questions that Nathan Ballantyne tackles in this terrific book are among the most important questions of our age. For example, how can we tell when our controversial beliefs are unreasonable? Why do intelligent, informed people reject our beliefs? Is it because they are biased? How can we know our own limits as inquirers? Unlike many philosophers of knowledge, Ballantyne focuses on the role of philosophy in providing inquirers with practical guidance. In particular, he offers a set of principles and observations intended to guide inquiry concerning controversial questions. His method helps us to confront our ignorance and shows us the difference between beliefs we have good reasons to doubt and those we don't. This book is not just an important contribution to philosophy. It also tells us how to improve our lives by helping us to use evidence to answer controversial questions. Highly recommended.

I’ve got three copies to give away. Send an email with ‘knowledge’ in the subject line to singalminded@gmail.com. Usually these contests are only open to North American readers — a point I need to make more explicit in the future — but this time around I have been told geography doesn’t matter. Many thanks to Oxford University Press. Remember that two copies go to anyone, and the third goes to a paid subscriber — one perk of susbcribing is a slightly higher chance of winning books. (Immediate post-email update: I forgot to include a deadline, but I’ll draw from all the emails I get before 10:00 pm Eastern tomorrow, November 5th.)

I hope everyone had a good weekend, chock-full of justified true beliefs.

Questions? Comments? 50-page single-spaced under-punctuated rants about Gettier cases? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.