This piece originally ran as a paywalled article on September 21, 2021. I’m unlocking it today and sending it out to my free subscribers because of the apparent end of Roe v. Wade. For what it’s worth, I strongly disagree with the view I am seeing online that this language fight had a significant causal impact on this epochal new blow in the abortion wars:

At the same time, this language change, which has been embraced by many important liberal institutions, wasn’t preceded by any sort of real debate. It felt like it occurred overnight, and I do think that, on balance, it probably has had a negative impact on abortion-rights advocates’ ability to persuade the persuadable, and that it probably sparks backlash for no good reason.

That being said, it’s really hard to know for sure. The point of this piece is less to make any strong claim about the causal impact of using phrases like “birthing bodies” and “pregnant people,” and more to argue that if you actually think through the way we use language, it’s unclear how anyone is actually being excluded by phrases like “pregnant women.”

As always, please consider becoming a subscriber if you’d like to support this sort of work.

We’re having a bit of a moment when it comes to the discussion over ‘inclusive’ language and concepts like pregnancy. That’s mostly because of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the ACLU.

First, on the September 7 episode of Anderson Cooper 360, AOC responded to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s defense of that state’s deeply draconian new abortion law, which bans the procedure after six weeks, as follows, according to the transcript:

Well, I find Governor Abbott’s comments disgusting, and I think there’s twofold [sic]. One, I don’t know if he is familiar with a menstruating person’s body. In fact, I do know that he’s not familiar with a woman — with a female or menstruating person’s body, because if he did, he would know that you don’t have six weeks.

It is that quote-unquote, “six weeks,” and I’m sorry, we have to break it down on you know, break down Biology 101 on national television, but in case no one has informed him before in our life -- in his life, six weeks pregnant means two weeks late for your period, and two weeks late on your period, for any person, any person with a menstrual cycle can happen if you’re stressed, if your giant [this should read ‘diet’] changes or for really no reason at all.

AOC is following the new progressive orthodoxy for how to talk about subjects like pregnancy and menstruation: It’s very important to not mention the fact that it is ‘women’ who experience these processes. AOC almost violated this by saying ‘woman’ in the first paragraph above, but quickly corrected herself to “female or menstruating person.” I think she could have gotten in trouble if she’d just said “female person,” because the rules are confusing — more on that in a bit.

Naturally, conservative and woke-skeptical types started making fun of AOC for the fact that as she’s claiming to “break down Biology 101,” she is using stilted language like “person with a menstrual cycle.”

She responded by defending her choice and inviting the haters to “stay mad.”

Then, on September 18, the American Civil Liberties Union tweeted a quote from Ruth Bader Ginsburg to mark the anniversary of her death.

You may have noticed some brackets in that screenshot. Here’s the original, unaltered quote, presented in full context by Louise Melling, “a Deputy Legal Director at the ACLU and the Director of its Ruth Bader Ginsburg Center for Liberty,” on the ACLU’s own website in 2020:

Writing in dissent in Gonzales v. Carhart, a case in which the court upheld a federal restriction on abortion, Justice Ginsburg plainly stated: “[L]egal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.”

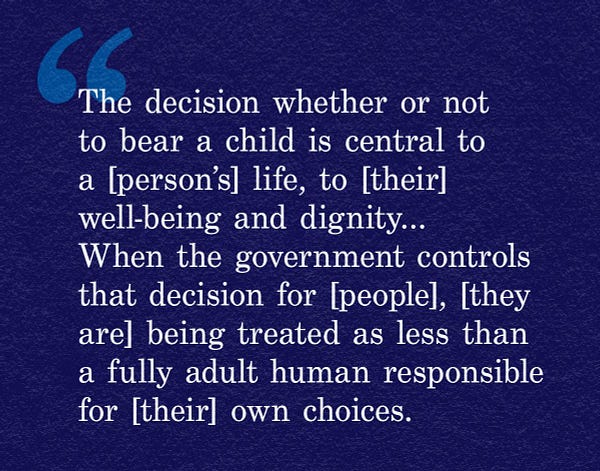

It was a point she had been making since her 1993 Senate confirmation hearings. In that hearing, Justice Ginsburg emphasized: “The decision whether or not to bear a child is central to a woman’s life, to her well-being and dignity. … When government controls that decision for her, she is being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for her own choices.”

The new, sanitized-for-2021 version:

The decision whether or not to bear a child is central to a [person’s] life, to [their] wellbeing and dignity... When the government controls that decision for [people], [they are] being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for [their] own choices.

So the ACLU took a quote in which arguably the most famous female jurist in American history spoke stirringly about the importance of defending women’s autonomy and dignity and expurgated from it any mention of womanhood.

You can probably understand why people are upset!

***

‘Inclusion’ is the one-word justification for stripping the concepts of girlhood and womanhood from all talk of menstruation, pregnancy, and so on. The idea, as AOC explained, is that since not everyone who experiences these processes identifies as a woman, we should use language that includes the full range of people affected. Some people who get pregnant identify as men, and others identify as nonbinary (neither women nor men), so phraseology like “pregnant people” and ‘menstruators’ does a better job pointing to the right people without causing anyone to feel left out.

It sounds great — who doesn’t want to be inclusive? — but if you examine this argument a bit more closely, it doesn’t quite make sense. It relies on certain misunderstandings about language, or at best unilateral decisions to change the definitions of well-established terms so that they mean “identifies as” rather than “has these physical features.”

Let’s acknowledge language can be fuzzy in this realm. Terms like ‘men’ and ‘women’ and ‘boys’ and ‘girls’ can serve different functions depending on the context. Sex and gender aren’t the same thing, and sometimes a given usage is more ‘about’ one than the other. If I point to a bearded adult human wearing a suit and tie and say “that man over there,” that could be seen as an utterance referring to both sex-stuff (the vast majority of people with a lot of facial hair are biologically male) and gender-stuff (with that suit of his, he is presenting the way males in our society present).

I do think that when people talk about this, they slightly overcomplicate it. Like, if someone pressed me on why I was calling the person a ‘man’ — what I was really saying — I’d stammer a bit and turn slightly red and eventually admit that really, the only coherent answer is that I was making a strong guess about his physical anatomy. What’s going on in my brain is something like “Beard and suit and tie —> masculine-coded —> male anatomy —> ‘he.’ ”

Of course things get more complicated with the idea that people should be allowed to choose their pronouns, which is something I am happy to go along with (except in some truly bizarre edge cases we can ignore for now). So if I was informed the beardy, male-seeming person went by ‘they,’ I’d use ‘they.’ I’d be switching, for the sake of politeness, from a system in which pronouns refer (at root, when you really get down to it) to someone’s biological sex to a system in which they refer to someone’s gender identity. Language is flexible; the world will continue to spin and the sun will come up tomorrow. But overall, ‘he’ still usually refers to biological sex, at root. I’m a ‘he’ not because I ‘identify’ as male — all these years later I still don’t understand what that means — but because I am physically, biologically male.

Whether or not you agree with my assessment of my own heness, it’s undeniably the case that sometimes when we say ‘girls’ or ‘women’ or ‘boys’ or ‘men,’ we are locked in quite specifically on biology and nothing else. When we refer to the effects of abortion laws on ‘women,’ we really do just mean “adult human females.” It doesn’t, and never has, had anything to do with how the adult human females in question identify, present, or anything else. To see why, imagine a sentence “We need to protect X’s rights to abortion,” where X refers to how people identify and where the sentence itself is coherent. I don’t think there’s any such sentence, because whether you can get pregnant and therefore might need an abortion has nothing to do with how you identify.

I know that that phrase “adult human female,” despite being right there in the dictionary, has now been successfully pathologized and is treated as borderline hate speech, but we really need it to understand what’s going on here linguistically. So, well, sorry!

Phrased less diplomatically: I think it’s idiotic to pretend that these terms don’t have certain clear-cut definitions everyone knows — if you want to say they shouldn’t have these definitions, be my guest (and good luck with your political project), but you can’t just start yelling at people for using a basic scientific term that is a human universal. AOC is pretending that sentences like “women need access to abortion” refer to people who “feel like” or “identify as” women, and that therefore we need to change our language. If she were correct, maybe she’d have a point, but her claim is clearly, plainly false.

Let’s imagine AOC had done her interview as a normal human rather than as Wokebot 5000. Maybe in her initial response, she would have told Cooper: “Well, I find Governor Abbott’s comments disgusting, and I think there’s twofold. One, I don’t know if he is familiar with a woman’s body.”

Now let’s swap out that eeeeeevil dictionary definition: “Well, I find Governor Abbott’s comments disgusting, and I think there’s twofold. One, I don't know if he is familiar with an adult human female’s body.’

Sounds a little stilted (if an improvement over Wokebotian), but this is perfectly accurate. Abortion is of concern to adult human females, who are known as ‘women.’ If you are a trans man or gender nonbinary, but you are in the bucket of people who have to deal with menstruation and pregnancy, you are female, and you are, by this strictly biological definition, a ‘woman.’ I am not going to misgender you or demand details about your reproductive anatomy or anything like that, but it’s just undeniably, definitionally the case that you are, in this specific context, encompassed in the sweep of the word ‘woman’ or its simple definition, “adult human female.”

In other words, no one’s being excluded here. There is no coherent sense in which nonbinary people and trans men are excluded from talk about women getting their periods or becoming pregnant or seeking abortions, once we recognize (or re-recognize, since it has been the case all along) that ‘women’ is being used in the strictest biological sense here, not to reference someone’s gender identity. This exhausting and time-consuming and self-sabotaging-to-the-left ‘debate’ really just comes down to very silly, freshman-level word games, and to demands that we not use the sort of plain, relatable everyday language vital to clear and frank political debate — vital to, for example, securing women’s rights and dignity.

To drive the point home a bit more, let’s remember that one manifestation of this unwillingness to treat plainly female people as ‘female’ has been to use increasingly sterile, anatomical language. Some people don’t identify as having certain body parts, or find mentions of them triggering (or so we are often told). That is, some people don’t like to hear ‘breastfeeding’ because that makes them feel bad about having breasts, so the term ‘chestfeeding’ pops up now and then. “It's time to add ‘chestfeeding’ to your vocabulary,” insisted some website called Today’s Parent in June. Subheadline: “I know we're all used to saying ‘breastfeeding,’ but as a lactation consultant, I believe that inclusive language is vital.”

It’s the same basic principle here. Some people might not like having breasts, or might not like calling them that, but they are certainly included in any discussion of ‘breastfeeding.’ Tomorrow, the euphemism treadmill could carry away ‘chestfeeding’ — this, too, could come to be seen as too feminine-coded and as running too high a risk of triggering dysphoria. Would it suddenly be the case that ‘chestfeeding’ didn’t ‘include’ everyone it meant to include? Of course not! We are talking about body parts and biological functions here, and the language we use to make certain basic observations and political claims. It would be terrible to feel dysphoric about your body, or to be in such a devastated psychological state mere mention of the names of your own body parts caused you anguish. But there’s no linguistic solution to that: In all likelihood, a new association will form with ‘chestfeeding’ and then that term will cause anguish. All along, though, it’s the same body parts, the same act, the same group of people who are being referenced. Maybe some people are being offended or triggered, but they aren’t being excluded.

It’s the same deal with ‘woman’/’female.’ I certainly have empathy for anyone who feels so at war with their own body that it causes them grief for them to simply hear the words that describe it, even if I have yet to fully grok this apparently-quite-common situation in which people are horribly dysphoric and can’t even bear the mention of ‘woman’ or ‘female’ but choose to… conceive and carry to term and give birth to and breast-feed a child. But they simply aren’t being excluded when we talk about “pregnant women,” because in this usage ‘women’ is simply an observation about their biology that has nothing to do with how they identify, in much the same way ‘breast’ is simply a reference to two things on their chest that has nothing to do with their feelings about having them or calling them that.

One more hypothetical: Let’s imagine we take this question to gender-critical feminists, who tend to be quite hostile to the idea that people can identify out of their biological sex. GC feminists are very opposed to language like “pregnant people” — they think it’s vital to maintain and defend the category ‘woman.’ So let’s tap a GC feminist on the shoulder, point to a nonbinary pregnant person, and say, “When you talk about all these rights and policies you want to apply to pregnant women, do you include this person, even though they say they aren’t a woman?”

One hundred out of one hundred GC feminists would agree that this nonbinary person is, in fact, included. Some of them would roll their eyes at how silly a question it is (or maybe how ‘daft’ a question it is, since many of the most prominent GC feminists are across the pond). Their policy is that adult human females deserve certain rights. It doesn’t matter how you identify. You cannot identify out of the capacity to become pregnant, anyway. These are simple, factual designations that have nothing to do with how anyone identifies. And there’s just no escaping the fact that we need terms for male and female people. Euphemisms can’t save us. Carving people up into more and more specific body parts can’t save us either, because eventually those terms, in addition to coming across as viscerally dehumanizing and ridiculous, will become too gender-coded and themselves offensive.

The simplest solution here is the best: Understand, as we all did until seemingly 30 seconds ago, that biological sex and gender identity are not the same thing, and that sometimes it is necessary to refer solely to people’s biological sex. All this bizarre linguistic pretzeling is an embarrassing spectacle that, by making progressives look hypersensitive and biologically illiterate and incapable of using normal everyday language, gives a tremendous amount of fuel to the political forces seeking to chip away at women’s rights.

Questions? Comments? Ideas for cool new biological sexes? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

NEW YORK, NEW YORK - NOVEMBER 19: The newly installed mural of the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg stands in Manhattan’s East Village on November 19, 2020 in New York City. The mural of the Brooklyn-born Justice is displayed on a wall above a restaurant and is by a New York-based street artist named “Elle.” The three-story-tall mural celebrates the life of the liberal icon who died of pancreatic cancer in September. She was 87 years old. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)