The Great Feminization Theory Has A Lot Of Soft Spots

(Part 2)

One fairly robust, consistent finding from social psychology is that conservatives are more sensitive to disgust than liberals. When it comes to anything involving germs or infection or impurity, conservatives, on average, are going to respond more viscerally.

That’s why, after the pandemic broke out in 2020, we saw everything break down along sadly predictable political lines. Republicans, activated by their higher-than-average fear of disease, quickly embraced harsh lockdown policies, masks, and vaccine mandates. Some of these policies, in retrospect, may have done more harm than good. But Democrats didn’t cover themselves in glory, either: First, they exhibited shockingly little concern for the fact that we were, in fact, in the early stages of a global pandemic. They protested even the early, less controversial lockdown measures and later refused to get vaccinated. Many of them became hardened deniers that there even was a pandemic, that the vaccines worked, or both.

Wait, I’ve got that all entirely backward: On average, it was liberals who were way more worried about the virus, and conservatives who were, almost from the start, skeptical of it. How can we explain that, in light of the available research?

Because life is not a lab. It’s very easy to generate effects in experimental studies that just don’t generalize to the real world. The disgust findings are real, but that doesn’t mean that they can be neatly translated onto real-world situations involving disease or disgust. Which tribes adopt which beliefs is so complex and overdetermined that psychology experiments are very unlikely to provide us with sufficient insight to predict this sort of thing before the fact.

Translating Average-Level Group Differences Into Explanations for Real-World Outcomes Is Difficult

A cople weeks ago I laid out some background that I think helps to put the argument over the “feminization” of society — and particularly academia — in the proper context. In this post I’m going to respond more specifically to the feminization arguments themselves.

As I noted in that last post, it was Helen Andrews who kick-started the present spate of focus on feminization, with a talk she gave at a conservative conference and an article adapted from it that was published in Compact. But some academics have been studying this precise question for a while in a more serious and, for the most part, less polemical manner.

Take, for example, the psychologists Cory Clark and Bo Winegard. In a 2022 article in Quillette running down some of their research, they noted that with women finally gaining parity, or even majority representation, in some corners of academia, “many emerging trends in academia can be attributed, at least in part, to the feminization of academic priorities.” The basic structure of their argument is to take certain observed or hypothesized average-level differences between men and women and then use them to explain aspects of academic culture — particularly the recent rise of illiberalism and “cancel culture” therein.

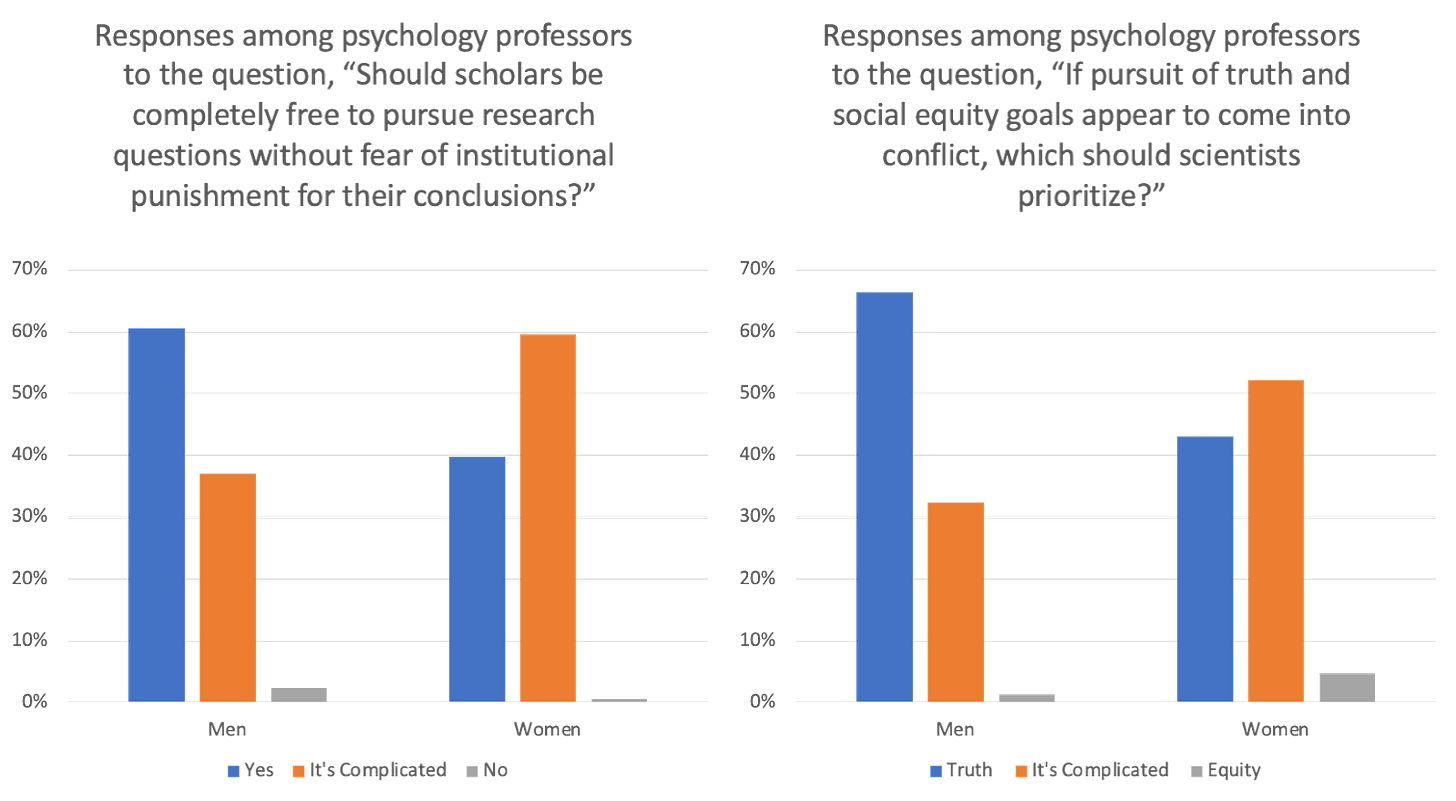

They note that, on average, women report being more open to censoring certain claims and punishing the speakers than men do. Their article included both national polling on this subject showing a pretty consistent gap in which men are generally free speechier as well as some of their own research. For example, a team led by Clark conducted a “2021 survey. . . [of] 468 psychology professors from over 100 top universities in the US” which showed that men were both more free-speechy and more likely to rate “pursuit of truth” as more important than “social equity goals” should the two conflict.

At the time of the Quillette article this was a preprint, but it’s since been published in final form here. It’s a pretty rich bit of survey data, and it highlights some of the complexities that need to be untangled to accurately understand this debate.

Winegard and Clark, to their credit, note in their article that “Of course, this pattern of change in academia is also confounded by ideology. Women are generally more left-leaning than men, and ‘equity and inclusion’ has become a major moral concern on the political Left with which academia is increasingly dominated. In our own data, however, female sex continues to predict lower support for academic freedom and lower prioritization of truth after controlling for political allegiance.”

That’s technically true, but sex didn’t stand out as particularly important compared to other factors in the final published research:

When gender, ideology, and age were simultaneously regressed on support for academic freedom, with small but not always significant effects, female professors (semipartial r = −.10, p = .048), more left-leaning professors (semipartial r = .11, p = .024), and younger professors (semipartial r = .22, p < .001) were less supportive of complete academic freedom.

Statisticians can get into arguments about the proper way of interpreting even fairly basic findings like this one, and I’m not going to stretch above my pay grade here. But the point is, those really big gaps in the above graph are arguably a bit misleading. The relationship between gender, ideology, age, and belief in academic freedom are tangled. For example, roughly speaking, “being young” was twice as good a predictor, in this sample, of being skeptical of capacious concepts of academic freedom (as the researchers describe it), as was gender and ideology, which had equal predictive power. And for what it’s worth, the female variable barely reached the traditional threshold for statistical significance, anyway.

So let’s temporarily grant that technically speaking, attitudes toward free speech on campuses are changing as a result of an influx of female faculty. Is this because they are younger, because they are leftier, or for other reasons? And to what extent does it make sense to shorthand all of this as them being female per se?

Male Versus Female Conflict

One could imagine a nerdier version of the feminization argument that noted that because women are, on average, more to the left than men, and because those on the left have different attitudes toward speech, the feminization of academia and other institutions might bring with it less tolerance for certain types of speech.

Clark, Winegard, and others go beyond that. They approach this through an evolutionary psychology lens that posits that what we’re seeing in “feminized” institutions might be the result of rather deep-seated differences in how men versus women handle certain basic elements of human social life. They sum up these differences in this manner in the Quillette article:

Men compete more overtly than women for status; they are the larger and more physically aggressive sex (especially as that aggression becomes mortal), and they are more contest-oriented, vying against each other openly. Women, on the other hand, compete more covertly, using relatively safer and often more subtle methods. Men also compete mortally against other groups of men and have therefore evolved traits and tendencies that encourage the creation and coordination of large coalitions with status hierarchies. Women, on the other hand, prefer egalitarian social relations when in large groups and are not as predisposed as men to coordinating in large groups. Consequently, women prioritize equality more than men.

Clark also gave an interesting talk on this subject at a University of Southern California–hosted conference earlier this year (I also spoke at it on — you guessed it — youth gender medicine stuff). In the talk she argued that men and women handle conflict differently, and that therefore, the feminization of academia can help to explain the rise of cancel culture:

When men get into a conflict, or a man does something wrong, his status takes a hit, he gets kicked down the hierarchy, he has to prove himself and earn his way back up. But he’s not kicked out of the group altogether because we can’t just afford to be kicking people out left and right when, you know, maximally large groups are more competitive — we want to make sure we’re taking advantage of everybody’s skills.

In contrast, for women, the solution would be if you’ve shown me that you’re a risky person, you’re a person who’s posing risks of harm to others, I don’t give a shit what you can contribute or do in the future. You’re out forever and you’re never welcome back. That is a more female-oriented strategy, and it is also the strategy that we see in cancel culture.

In academia (and journalism, for that matter), here’s how this usually goes down: When someone says something that is “harmful,” that is construed as them posing a threat to others, and therefore they are kicked out of the group.

As with all of these arguments, the problem is that we don’t have access to a parallel-universe simulator. We can’t put a male-dominated group and a female-dominated group in the exact same situation and see which differences emerge. But historically speaking, it seems pretty obvious that men, especially during times of political ferment, can be quite eager to adopt ostracization in response to conflict.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Singal-Minded to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.