Some Criticisms Of Effective Altruism Are Silly And Far Too Hypothetical

You can be an effective altruist without being an online weirdo utilitarian fundamentalist

Starting last year, I decided to donate a portion of this newsletter’s annual profit to GiveWell, an effective altruism organization. I stole the idea from Matt Yglesias.

I plan to make the same donation this year. Some people would argue this is not a good use of my finite donation funds. After all, these are boom times for critics of effective altruism, or EA, which philosopher (and EA doyen) Will MacAskill defines as “using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.”

First, MacAskill’s book What We Owe The Future came out and got a great deal of media coverage, casting a mainstream light on both EA and longtermism, or “the view that positively influencing the long-term future is a key moral priority of our time.” MacAskill and a lot of other folks in and around EA are longtermists, and there are various flavors of this movement, some of which are a bit crazy (we’ll get to that). Then, Sam Bankman-Fried, who is closely affiliated with a lot of EA folks (including MacAskill), and who declared his intention to give away his vast fortune to EA-friendly causes… well… I don’t know where to begin, but he appears to have run a mind-boggling crypto scam. (I should say that I haven’t read MacAskill’s book, but I have read some of the coverage, such as this great New Yorker profile by Gideon Lewis-Kraus, which also covers the origins of MacAskill’s relationship with Bankman-Fried.)

It’s understandable, given the growing awareness of longtermism’s weirdness and influence on EA, and given that Bankman-Fried will likely turn out to be a world-historic con man, that people are taking their shots at EA. But a lot of the arguments I’m seeing don’t really hold water, and I think we should distinguish them from legitimate critiques of EA — especially because one of the more admirable things about EA is that it tends to be very open to criticism!

Now, I’m potentially biased here for two reasons: first, the aforementioned annual donation. Of course I don’t want it to turn out that I donated to an unworthy cause. Second, I have a relative who now works at GiveWell, which could introduce bias in the form of my wanting his organization to do well, in part so he can do well. (He applied for the job long after I started my annual donation practice.) So keep that in mind as you read what follows.

Anyway, EA is inextricably intertwined with utilitarianism, which the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines as “the view that the morally right action is the action that produces the most good.” That’s because a lot of EA folks are deeply committed utilitarians. While anything more than a gloss on this issue would balloon this post to unmanageable length, utilitarianism, as reasonable-sounding as it is, quickly gets weird. If you follow it down its own logic, it appears to lead to repugnant conclusions, including one helpfully called the repugnant conclusion.

As the neuroscientist and novelist Erik Hoel writes, in an essay to which we will return:

The term “repugnant conclusion” was originally coined by Derek Parfit in his book Reasons and Persons, discussing how the end state of this sort of utilitarian reasoning is to prefer worlds where all available land is turned into places worse than the worst slums of Bangladesh, making life bad to the degree that it’s only barely worth living, but there are just so many people that when you plug it into the algorithm this repugnant scenario comes out as preferable.

“Shut up and multiply,” say the hardcore utilitarians — don’t let your intuitions or your heart get in the way of choosing the morally correct option. And the math isn’t even close. For the sake of a repugnant conclusion thought experiment, let’s assign 90 utils to an excellent life and 10 utils to a barely tolerable life, and then look at the difference between a scenario in which there are 10 billion humans inhabiting a utopian Earth and a scenario in which 1 trillion humans are living lives that are just barely tolerable, in a hellish interstellar dystopia consisting of nothing but AI-ruled prison planets.

10 billion lives × 90 utils = 900 billion experienced utils

1 trillion lives × 10 utils = 10 trillion experienced utils

To the committed utilitarian, it isn’t even close: Given the choice, colonizing planet after planet with imprisoned, wretched masses of humans who just barely want to be alive isn’t just better than a utopian situation involving Earth and only Earth — it’s so much better that the comparison is ridiculous. If (1) you hold that certain choices made today will affect whether humanity is able to seed our solar system and eventually other stars with more human life, (2) you view those potential lives as adding to the total amount of good created, and (3) you are committed to shutting up and multiplying, then this is how longtermism gets weird. When billions of potential future lives are at stake, and you grant those lives as much weight as current ones, then it’s only natural you’d be willing to maybe sacrifice a continent or two here on Earth for the sake of generating many descendants (and a lot of utils). (Note that if you change the number of utils assigned to good versus bad lives, it won’t change the overall story much — it’s the quantity of lives that quickly renders the math weird.)

This sounds like supervillain stuff, and the fact of the matter is that it’s mostly a thought experiment and an example of how weird utilitarianism and longtermism can get. I have to confess that I have never been able to understand the logic here. I just can’t grok why we should view a future potential life as equal to a currently existing one. Someone who currently exists can suffer and feel pain and be mourned by their loved ones. Someone who doesn’t exist yet… doesn’t exist yet. If they never come to exist, they are not experiencing any negative consequences. My brain sort of returns a divide-by-zero error when I try to stack up a happy life against a nonexistent life. You can’t compare them! The nonexistent life doesn’t exist, so it has no happiness level. (If you find this stuff interesting, the nonidentity problem is a good way into it.)

Anyway, it’s not unusual for these sorts of conversations to blast off quickly into strange territory. But you don’t need to invoke tragic, galaxy-spanning space operas centering on prison planets to understand why utilitarianism is weird. There’s also the psychotic surgeon.

The psychotic surgeon is an offshoot of the trolley problem, and like that problem, it is an oft-chewed-over hypothetical that utilitarians and their critics debate. It goes something like this: There’s a psychotic surgeon who is committed to saving as many lives as possible via unlicensed organ donations. So he snatches people off the street, murders them, and then makes sure as many of their vital organs as possible save the lives of people on donation wait-lists.

Again, if you shut up and multiply, you will have a lot of trouble coming up with a substantive argument against letting the psychotic surgeon do his thing. If he can save seven lives by killing one person, why not? And the devilish thing about utilitarianism is what happens when you make concepts like joy and hope and terror fungible. Sure, the people he murders experience brief moments of terror before their demise, but aren’t the folks languishing in hospitals at the precipice of death also feeling terror? If you have to cause a bit of terror to alleviate a lot more terror, why not?

I’ll leave my general remarks about utilitarianism at that; I’m far from an expert and couldn’t possibly do justice to a debate that has raged in one form or another for centuries. If you want to hear more about it, you can listen to Sam Harris interviewing Erik Hoel, a thoughtful EA critic (again, we’ll return to him soon).

For me, what it comes down to is that many criticisms of utilitarianism seem quite fair and difficult to wriggle out of, but I’m just not sure how much they matter to my decision to donate to EA causes versus others. I also think there’s a slipperiness here that could allow anyone to attack any institution that engages in cost-benefit analysis on the grounds that it is “utilitarian,” which (as we all know) is a broken morality system that involves a lot of deranged surgeons running around slicing people up.

For example:

A: “I’m going to donate to GiveWell because they carefully study the impact of the charities they recommend.”

B: “Oh, so they want to maximize the overall good? That sounds a lot like utilitarianism to me! What’s next — are they going to populate a bunch of planets with wretched people in some sort of sick utility-maximizing scheme, or give money to homicidal surgeons?”

I think it should be pretty clear why B’s argument doesn’t make sense. In giving money to GiveWell, I am not endorsing utilitarianism in all its forms, in every context. I am endorsing the ideas that 1) I want my money to do as much good as possible in the context of this one annual donation, and, relatedly, 2) if an organization raises money for the purpose of doing good, there should be some accountability there. Often there isn’t!

If that’s utilitarian — I mean, I guess? If you’re going to slag EA for being bad “cuz utilitarianism,” you should also explain why your strategy for charitable giving is better, especially if it concerns efforts that don’t engage in the sorts of vetting, program evaluation, and transparency that GiveWell does. In other words, it could both be the case that it would be disastrous to take GiveWell-style logic too far and apply it to every sphere of human life (“Why should I nurture my kid? That money and time could save 20 African kids!”), and that on the narrow question of charitable giving, this sort of approach gets you the best bang for your buck as a donor.

“Sure,” you might respond, “but the EA community is composed of very specific people doing very specific things, and a lot of those people are committed utilitarians of the at-least-slightly-weird variety. For example, that Lewis-Kraus profile portrays MacAskill as a guy who actually holds some pretty wacky beliefs about things like longtermism, but who is adept at hiding them when giving media interviews.”

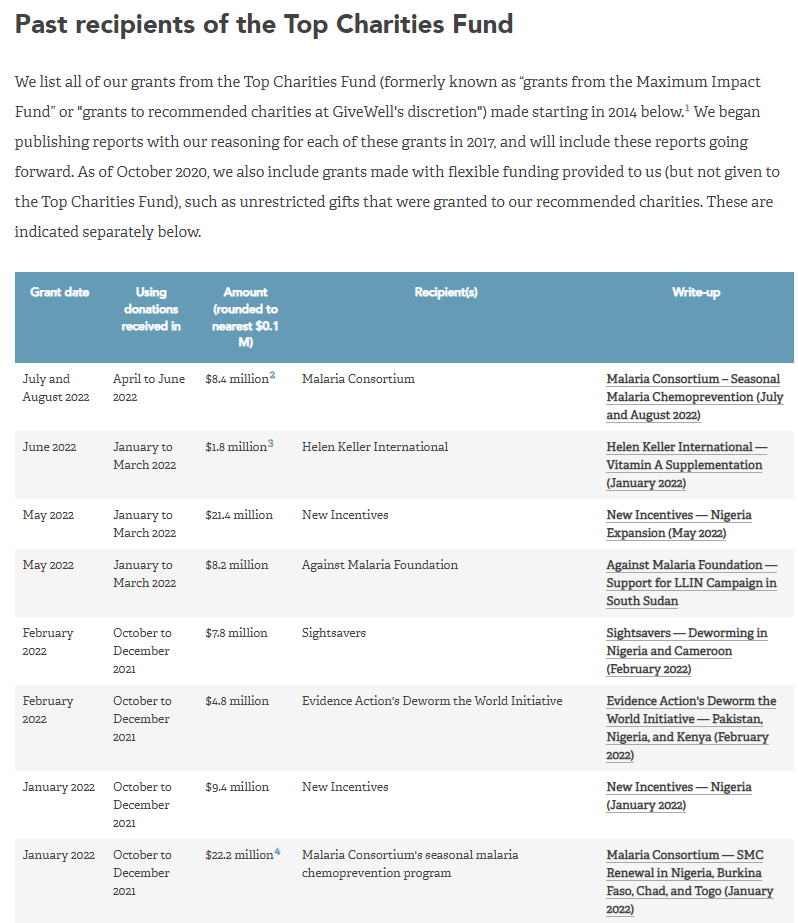

That may be, but I’m not giving money to Will MacAskill or weirdos on Reddit. I’m giving money to GiveWell, and GiveWell is, again, pretty transparent about the causes it supports. It is very concerned with helping present-day, real-life people: If you go to the organization’s Top Charities Fund page, you’ll see that it favors charities engaged in efforts to, for example, fight malaria and prevent blindness, generally in poor regions that lack access to quality healthcare.

So is “Effective Altruism” GiveWell, or is it Will MacAskill, or is it the weirdest corners of rationalist Twitter? I think those distinctions are getting melted down by the heat of internet discourse, and there’s some serious cherry-picking and conflation going on.

For example, one of the sillier knocks on EA came in the form of this tweet (archived here):

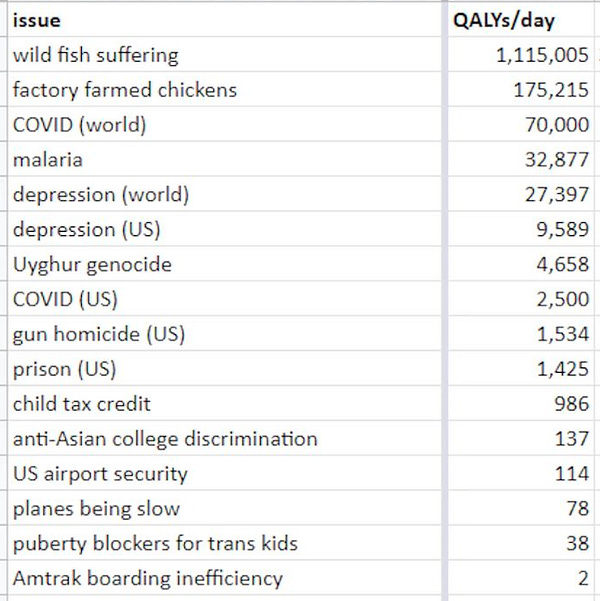

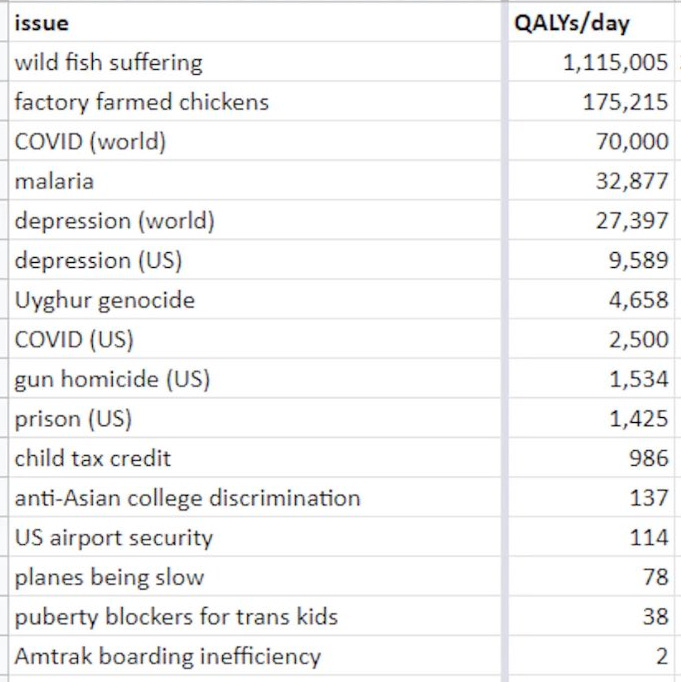

Yes, I know, it’s just some rando — we’ll get to the non-randos soon — but this is what I’m talking about. It’s just a strange spreadsheet stripped of any context:

A QALY is a “quality-adjusted life year,” or, according to Wikipedia, “a generic measure of disease burden, including both the quality and the quantity of life lived.” So someone, somewhere, made a spreadsheet determining that if you do weird utilitarian math, no one experiences as much suffering as wild fish. O… kay? There is a multi-link chain of rumors that might connect this spreadsheet to Bankman-Fried’s alleged ex-girlfriend, Caroline Ellison, but even then: O… kay? Bankman-Fried’s ex did a weird spreadsheet that had effectively no real-world implications. If GiveWell said they were giving my money to alleviate the suffering of wild fish (maybe by committing icthyocide against the fish species that prey on them, which, if you shut up and multiply, is obviously the right move), I would obviously look for a different charity.

On to non-randos: This piece by MSNBC columnist Zeeshan Aleem, “How Sam Bankman-Fried’s fall exposes the perils of effective altruism,” is strange and illustrative. Aleem insists that “if one pays close attention to the more unsettling ideas behind how effective altruism works, it should become apparent how this whole debacle unfolded.”

What are those ideas?

It is a belief system that bad faith actors can hijack with tremendous ease and one that can lead true believers to horrifying ends-justify-the-means extremist logic. The core reason that effective altruism is a natural vehicle for bad behavior is that its cardinal demands do not require adherents to shun systems of exploitation or to change them; instead, it incentivizes turbo-charging them.

I’d love for Aleem to list some belief systems that bad faith actors cannot easily hijack. It’s even weirder for him to accuse EA of failing to “require adherents to shun systems of exploitation or to change them,” because this is true of the vast majority of charity efforts. Every night in Manhattan there is some benefit gala with very fancy people raising money for what they believe are very important causes. Then, every morning, the attendees go back to their jobs participating in the worst and scammiest and most exploitative parts of our financial system.

Some more from Aleem:

The value proposition of this community is to think of morality through the prism of investment, using expected value calculations and cost-effectiveness criteria to funnel as much money as possible toward the endpoint of perceived good causes. It’s an outlook that breeds a bizarre blend of elitism, insularity and apathy to root causes of problems. This is a movement that encourages quant-focused intellectual snobbery and a distaste for people who are skeptical of suspending moral intuition and considerations of the real world. The key to unlocking righteousness is to “shut up and multiply.” This is a movement in which promising young people are talked out of pursuing government jobs and talked into lucrative private sector jobs because of the importance of “earning to give.” This is a movement whose adherents are mainly people who went to elite schools in the West, and view rich people who individually donate money to the right portfolio of places as the saviors of the world. It’s almost like a professional-managerial class interpretation of Batman.

I don’t want to get bogged down here but again, there’s a lot of weirdness. First: “The value proposition of this community is to think of morality through the prism of investment, using expected value calculations and cost-effectiveness criteria to funnel as much money as possible toward the endpoint of perceived good causes.” I think it’s clear from context that Aleem does not mean this in a complimentary way. But what is charitable giving if not an investment? Or it should be, at least, because supposedly the point is for the money to leave your account and then go into someone else’s account and then go out into the world and help people. How else should we measure the effects of charitable giving if not via “expected value calculations and cost-effectiveness criteria”? Very few critics of EA seem to answer that question, and Aleem doesn’t proffer an alternative.

As for Aleem’s claim that “This is a movement that encourages quant-focused intellectual snobbery and a distaste for people who are skeptical of suspending moral intuition and considerations of the real world,” doesn’t it depend? Yes, there are EA-focused rationalists who have become convinced, as a result of thought experiments, that it might be moral to sacrifice one million human lives for a 15% chance to seed the stars with human life, or whatever, because Shut Up And Multiply. But then there are the EA groups, foremost among them GiveWell, that do the most work out in the real world (rather than in weird internet forums). Are they focused on the strange and inhumane and cold-blooded stuff of utilitarianism-on-steroids thought experiments? No! They are attempting to fight blindness and supply mosquito nets to prevent malaria and so on. If you’re not even going to grapple with that fact, it suggests you’re not interested in good faith rather than demagogic criticism of EA.

And I do think what Aleem is doing here borders on demagoguery. For example: “This is a movement in which promising young people are talked out of pursuing government jobs and talked into lucrative private sector jobs because of the importance of ‘earning to give.’” You know what else pushes promising young people into lucrative private sector jobs? Everything! This is a very well-known problem at places like Princeton University, and it’s embarrassing — kids with everything going for them, who could do just about anything they want, decide to enter amoral, money-oriented fields just to rake in as much cash as possible. It’s been an issue forever. It’s very silly to claim that effective altruism, of all things, is a root cause of that dynamic, simply because some have argued for this approach, and because it’s what Bankman-Fried did. I promise you ambitious 22-year-olds don’t need philosophical movements in order to be convinced to chase dollars and status. It’s almost like saying the reason so many teenagers are interested in sex is because of risqué HBO shows.

Last thing on Aleem’s article:

Mainstream effective altruism displays no understanding of how modern capitalism — the system that it eagerly chooses to participate in — can explain extreme destitution in the Global South or the vulnerability of our society to pandemics. This crowd seems clueless about the reality that funding research into protecting against dangerous artificial intelligence will be impotent unless we structure our society and economy to prize public safety over capital’s incentive to innovate for profit. If longtermists want to mitigate climate change, they should probably be radically reappraising an economic system that incentivizes short-sighted hyper-extractionism and perpetual growth.

Ah, okay, so your gripe is with capitalism, and you are mad EA is not committed to fighting capitalism. This is ridiculous. EA’s goals are to do the most good in the world we currently inhabit. That’s why GiveWell focuses on meat-and-potatoes charity issues in the developing world. What would it even mean to fund attempts to reappraise the worldwide capitalist system? Why would an organization focused on quantifiable do-goodery possibly enter that sort of morass? If Aleem wants to blame capitalism for global poverty and oppression (a massive oversimplification, to say the least) and call for some sort of worldwide economic revolution, that’s his right, but it’s very strange to accuse pragmatically focused organizations of not joining you in that quixotic effort.

***

Erik Hoel’s Substack essay “Why I am not an effective altruist” and its follow-up “We owe the future, but why?” are stronger, better-faith critiques of EA than Aleem’s, but I think they do a better job demonstrating the problems with living a life of radical utilitarianism than they do demonstrating the problems with EA.

Here’s how he lays out his thesis in his first essay:

For despite the seemingly simple definition of just maximizing the amount of good for the most people in the world, the origins of the effective altruist movement in utilitarianism means that as definitions get more specific it becomes clear that within lurks a poison, and the choice of all effective altruists is either to dilute that poison, and therefore dilute their philosophy, or swallow the poison whole.

This poison, which originates directly from utilitarianism (which then trickles down to effective altruism), is not a quirk, or a bug, but rather a feature of utilitarian philosophy, and can be found in even the smallest drop. And why I am not an effective altruist is that to deal with it one must dilute or swallow, swallow or dilute, always and forever.

The “poison” is the aforementioned homicidal surgeons and weird longtermist math and so on. Hoel believes that you can’t really correct this since it’s intrinsic to utilitarianism, and he makes a clever comparison: “Just as how Ptolemy accounted for the movements of the planets in his geocentric model by adding in epicycles (wherein planets supposedly circling Earth also completed their own smaller circles), and this trick allowed him to still explain the occasional paradoxical movement of the planets in a fundamentally flawed geocentric model, so too does the utilitarian add moral epicycles to keep from constantly arriving at immoral outcomes.”

Hoel then makes two important allowances: First, he notes that “utilitarian logic is locally correct, in some instances, particularly in low-complexity ceteris paribus set-ups, and such popular examples are what makes the philosophy attractive and have spread it far and wide.” Then, later in the essay, he explains that overall he likes effective altruism and thinks — italics his — “effective altruists add a lot of good to the world.” (Emphasis his throughout.)

But, he argues, EA can do good in the world only by diluting the philosophy that birthed it:

[T]he effective altruist movement has to come up with extra tacked-on axioms that explain why becoming a cut-throat sociopathic business leader who is constantly screwing over his employees, making their lives miserable, subjecting them to health violations, yet donates a lot of his income to charity, is actually bad. To make the movement palatable, you need extra rules that go beyond cold utilitarianism, otherwise people starting reasoning like: “Well, there are a lot of billionaires who don’t give much to charity, and surely just assassinating one or two for that would really prompt the others to give more. Think of how many lives in Bengal you’d save!” And how different, really, is pulling the trigger of a gun to pulling a lever? [The lever is a reference to trolley problem–type scenarios.]

First, I’d like to stake out the bold stance that it would be bad to murder billionaires to try to terrify other billionaires into donating to EA causes. That out of the way, I just don’t understand what he means that the EA movement “has to” conjure a swirl of justifications to restrain people from sociopathic behavior. From my (admittedly limited) interactions with GiveWell folks, I’m just not seeing any signs of dangerous utilitarian fundamentalism. I do not think anyone who works there, say, neglects their own children because helping children in sub-Saharan Africa would be much more cost-effective (which surely it would be!).

I think Hoel’s take, like a lot of the other takes out there, pays too much attention to utilitarianism’s online weirdos and too little attention to how legitimate organizations within EA operate. What these organizations show is that EA is actually the sort of constrained decision-making scenario in which, as Hoel allows, something utilitarianism-ish can work pretty well: It’s really just about what sorts of charitable donations folks with a bit of extra money should make. There is no radical movement to live one’s every waking moment in accordance with utilitarian precepts, which would of course be psychotic.

So overall, I just think Hoel’s argument makes more sense as “Why I Am Not A Utilitarian” than “Why I Am Not An Effective Altruist.” I just can’t emphasize enough how easy it has been to decide to give to EA causes while spending almost zero time (other than this essay) mucking about in the swampy lowlands of Utilistan. That’s partly because — and this is another fact critics of EA often leave out — the world of charitable giving has long been really, really bad at the sort of research and transparency and self-correction that EA organizations advocate and seem to practice. Hoel’s essay was actually submitted as part of a contest to award money to the authors of the best criticisms of EA. Now, that contest was funded by the FTX Foundation, which, whoops, but the fact remains that EA is good at this sort of thing: In September, GiveWell announced its Change Our Mind contest, which looks similar, and the organization also has a page logging “Our Mistakes.”

The push to make charity better doesn’t come just from nerdy philosophical types — Charity Navigator is another example — and the fact is that these efforts represent a vital improvement over how things were done in the past. It’s much, much better for wealthy people to give their money to organizations that have practices in place to ensure solid bang for the buck than it is for them to throw their money at whatever random glossy philanthropic cause catches their eye (perhaps because its galas are le-gen-dary). This argument stands on its own, without any references to horrifying futures in which a trillion humans languish on prison planets.

I want to make a couple final points about Hoel’s philosophical claims, because I think they actually highlight why people like utilitarianism, and why it’s often difficult to come up with alternatives that don’t smell pretty similar.

In Hoel’s second essay, he quotes Will MacAskill saying the following:

It is very natural and intuitive to think of humans’ impact on wild animal life as a great moral loss. But if we assess the lives of wild animals as being worse than nothing on average, which I think is plausible (though uncertain), then we arrive at the dizzying conclusion that from the perspective of the wild animals themselves, the enormous growth and expansions of Homo sapiens has been a good thing.

(Again, things just get so weird when you try to determine what is “better” or “worse” than “not existing.” It just breaks my brain.)

Hoel responds by pointing out that this is a good example of what happens when you treat morality as a simple exercise in measuring “good dirt” versus “evil dirt,” treating both as fungible — as in, a hiccup is a little bit of bad dirt, but if you pile up enough hiccups you’ll eventually have so much bad dirt, it’s equivalent to genocide.

He writes:

MacAskill’s error in lumping wild animals into the “evil dirt” category is due to misunderstanding a qualitative aspect of morality, an old verity which goes back to Plato: it is a good when creatures enact their nature. A polar bear should, in accordance to its platonic form, act true to its nature, and be the best polar bear it can possibly be, even if that means eating other animals. In turn, humans preventing it from doing that is immoral, an interference with the natural order. This is why the vast majority of people agree that polar bears dying out is bad, even if they occasionally eat seals, which causes suffering. [citation omitted]

I certainly agree with Hoel about the good and evil dirt, but don’t we need some way to compare harms? Let’s just accept, for the sake of argument, that old verity handed down to us from Plato: “It is a good when creatures enact their nature.” Polar bears certainly have natures. But seals also have natures — they don’t want to be eaten, or to have their offspring be eaten. Humans have natures as well — our own nature involves building permanent settlements that might interfere with polar bear habitats and, in the long run, building so many of those settlements, not to mention other stuff, that polar bears (and seals) may go entirely extinct.

Like everyone else I want to save the polar bears, but my point here is simply that “it is a good when creatures enact their nature” doesn’t actually get us very far in making moral decisions, because at some point, one thing we value is going to have to trump some other thing we value. Which should we value more? Conflicts are inherent to nature. And I don’t understand how Hoel could explain why we shouldn’t let a polar bear eat a human baby without engaging either in utilitarian math (the harm to the baby and its parents and family from being eaten far outweighs the harm to the polar bear being denied a single — and, let’s be honest, not very caloric — meal) or introducing his own epicycles (sure, creatures should be allowed to enact their nature, but of course there are exceptions in which no, we shouldn’t let them do that at all). Maybe he’d reply that this is the sort of constrained moral choice where utilitarianism does work pretty well, but there are a lot of much more complex scenarios in which that cop-out won’t work, but in which it’s still necessary to pick a “winning” side.

Utilitarianism can definitely get very weird, very quickly, and anyone who adopted it in a truly fundamentalist sense would become a monster, but I think it has a hold on people because it does provide a method for working through moral problems that at least seems relatively straightforward and intuitive — probably too straightforward and intuitive.

The other philosophical point I wanted to make involves, as all good philosophical thought experiments do, having sex with a dead dog.

Toward the end of his second post, Hoel highlights a “collection of recent tweets from different people who self-describe as effective altruists.” He later clarifies that these are all paraphrased so as to protect the weirdos who tweeted them, but one of them is:

It’s not morally wrong for someone to have sex with their dead dog, provided no one knows about it and the body is put back. The disgust you feel at this is not an argument against it.

Hoel sees this as a self-evidently ridiculous argument. So ridiculous he doesn’t explain why. “This is your brain on utilitarianism” is the point.

But, God (and dog-lovers) help me, I think thought experiments like this are really useful, and that it isn’t self-evidently clear why this would be morally wrong. Disgusting, yes! I’m grossed out by it. But a lot of people are disgusted by a lot of things, and I think this anonymous EA weirdo is absolutely right that disgust is not an argument. In fact, disgust has often been used to justify positions we now view as morally backward, such as the criminalization of consensual gay sex.

In much the same way I genuinely wanted to know more about Hoel’s view on the polar bear question, I wanted to know more about his view on the — well, dead dog question. Why is it wrong? What argument is there other than disgust? Does the corpse of a dead dog have rights? If we took that view seriously, it would lead to a lot of strange and likely undesirable outcomes elsewhere. Or maybe the argument is that, more generally, a range of unusual sexual interests are wrong because they go against “our nature” as humans? But that’s just a different version of old evangelical arguments against gay marriage.

My point is — I cannot emphasize this enough — not to defend hypothetical dead dog buggery, but simply to point out that morality is difficult and weird! It’s easy to point at the weirdos on the internet, with their psychotic surgeons and AI prison planets, and recoil at the horror of it all, but it’s harder to come up with genuinely better alternatives. Maybe there aren’t any — maybe morality is just too damn weird for there to be any hard-and-fast rules that can be universally applied. But it’s a bit too breezy to say, “Why are these weirdos ignoring ancient truths like ‘Let things be true to their nature?’” without actually grappling with where those sorts of belief systems would lead.

I hope GiveWell keeps doing what it’s doing. If it starts developing an interest in using my money to ease the suffering of wild fish, or fighting against potential future AI demon-gods, I’ll take my money elsewhere.

Questions? Comments? Attempts to solve this whole “morality” thing? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The image comes via DALL-E, produced by the prompt “a menacing robot giving food to a hungry child.”

Philosopher: I need you to fuck a dog.

EA: Done

Philosopher: No, wait, it's gotta be a dead dog.

EA: Hold on a second... done.

Philosopher: Great, this will be a really useful thought experiment for philosophy.

EA: A what for what?

I am skeptical of EA and utilitarianism in general, for various unoriginal reasons... but also a GiveWell donor. They're great! I don't think you really need to be a utilitarian or any particular philosophy to think, "money should be given to charities that prove they are spending it well", and that seems to be their basic operating principle, so good on 'em.

I sometimes wonder if maybe someone at GiveWell, through a utilitarian calculation said, "if we start supporting the weird causes EA gets into, we will start losing donors. So we're obligated to support good, popular causes as effectively as possible to ensure people who aren't necessarily true believers in EA help us continue to do our good work". And if they did, I'd be fine with that; it's working.