I’m lucky in a lot of ways, and one of them is that every so often I’m able to hop on a plane in New York and, five or six hours later, hop off that plane having been conveyed thousands of miles to the west. I’m writing this from my friend’s home in Burbank, California, having returned, early this afternoon, from a couple days in and around Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, a place I had never heard of that has spectacular landscapes like the one you see above this text. It’s special there — as a Brooklynite, it’s like visiting another planet. (Good bagels are a problem, though.)

Okay, one more:

Did Aramark Throw Two of its New York University Employees Under the Bus?

Over the weekend, New York Magazine published a story I’d been working on awhile about what really happened in the wake of a controversy that engulfed New York University last year, after some students said they were offended by the offerings at a Black-History-Month-themed dining-hall meal. Aramark and NYU blamed the whole thing on two Aramark employees, who were fired as a result. Emails suggest that this may have not been the full story. If you can suspend your disbelief long enough to imagine a corporation in the midst of a PR crisis not acting with complete honesty and integrity, you might enjoy this one.

Allow Me to Literally Pummel You Mercilessly With Some Words About Why Words Shouldn’t Be Considered Violence

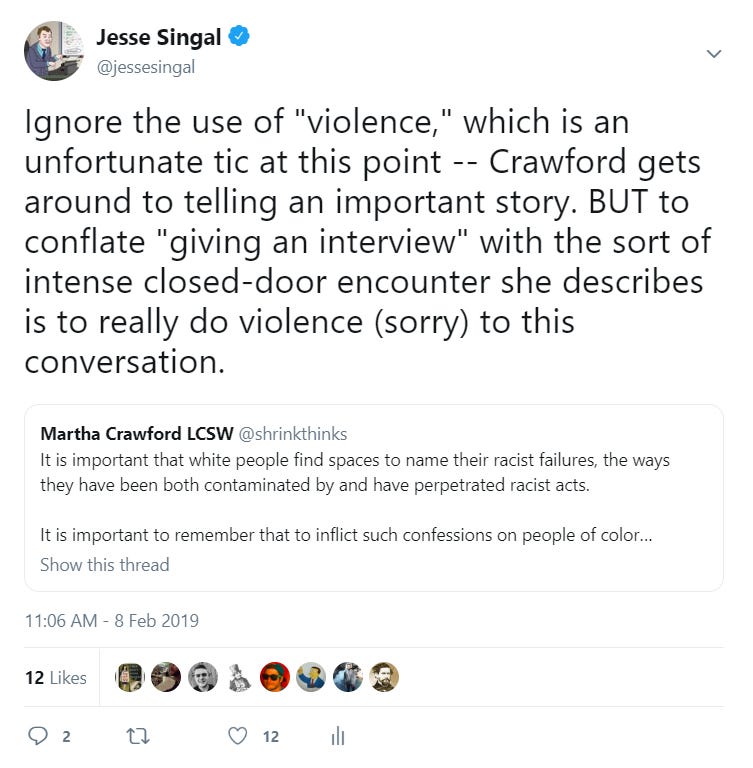

Last week I tweeted the following in response to a thread by a psychotherapist and social worker named Martha Crawford, who was in turn reacting to Liam Neeson’s admission that when he was younger, he harbored racist revenge fantasies after a friend was raped:

The thread in question does, in fact, get to an important story about what was (in effect) a diversity-training-gone-very-wrong at a Brooklyn clinic where Crawford did a social-work internship. The key bits start here and you should read them if you get a chance. But, more importantly for our purposes, Crawford pushed back on my criticism of the words-are-violence trope. Which got me thinking about why it bugs me.

Some of this I’ve laid out before. I don’t think it’s a good idea to teach people, particularly young ones, that it’s common for words, on their own, to cause trauma or other forms of lasting harm. At the most basic level, these claims just aren’t very accurate. When people make them, they tend to exaggerate or conflate or confuse certain things — in the linked-to article, for example, I critiqued a New York Times column by the Northeastern psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett on the following grounds:

Setting aside the fact that no one will ever be able to agree on what’s “abusive” versus what’s “merely offensive,” the articles Barrett links to [as evidence of the ostensible link between offensive speech and physical harm] are mostly about chronic stress — the stress elicited by, for example, spending one’s childhood in an impoverished environment of serious neglect and violence. Growing up in a dangerous neighborhood with a poor single mother who has to work so much she doesn’t have time to nurture you is not the same as being a college student at a campus where [Milo] Yiannopoulos is coming to speak, and where you are free to ignore him or to protest his presence there. One situation involves a level of chronic stress that is inflicted on you against your will and which really could harm you in the long run; the other doesn’t. Nowhere does Barrett fully explain how the presence on campus of a speaker like Yiannopoulos for a couple of hours is going to lead to students being afflicted with the sort of serious, chronic stress correlated with health difficulties. It’s simply disingenuous to compare the two types of situations — in a way, it’s an insult both to people who do deal with chronic stress and to student activists.

Now, even if mere words don’t usually cause lasting physical harm on their own, there could be an aspect of self-fulfilling prophecy here. If you tell young, malleable people over and over that they are being harmed by types of speech that are rather prevalent in society — turn on a.m. radio anywhere and you’ll quickly be able to find far-right demagogues — that could, in the long run, be harmful to some of them. (Though I of course don’t want to overstate this argument, either.) And, again, it’s needless potential harm when the arguments for this link basically boil down to “Offensive speech something something something chronic-stress health effects.” There’s just no good evidence to suggest occasional exposure to offensive speech brings with it negative health effects with any real frequency.

But let’s dig just a little bit deeper into this. The more I thought about Crawford’s response, the more I realized that my qualms about speech-as-violence claims stem largely from the fact that there’s such a society-wide consensus on what violence is. Everyone agrees that even just a single moment of genuine violence can kill someone or ruin a life (or multiple lives), and because of this, just about everyone agrees that it is okay for the state to intervene to prevent violence and to punish those who perpetrate it.

Violence, as most people understand the term, is the only category of human action that has these sorts of properties. No non-violent act committed by one human against another can kill or maim that person in the short term, except in ultra-outlier cases (you are so offended by my comment you have some sort of devastating physical reaction to it), and so the question of what speech should be prevented or punished by the authorities is much more hotly contested than the question of whether it’s okay for authorities to intervene to prevent and punish violence. Even intense forms of speech that just about everyone agrees merit a response from the authorities — violent interpersonal threats delivered via phone, anonymous bomb threats, and so on — while deeply unpleasant and scary to be on the receiving end of, do not, on their own, cause physical harm of the sort associated with violence.

Violence, in short, is very different from not-violence. So when I see people try to expand the definition of ‘violence’ to include things that, according to the standard dictionary definition, aren’t violence, it worries me. What’s their goal in doing so? How does calling something that is hurtful or offensive or bigoted or menacing violence make the world a clearer, more easily understood place? Why not just call it hurtful or offensive or bigoted or menacing?

One simple answer simply has to do with the internet’s attention economy. If I say “X is offensive,” I’ll get a lot less attention, sympathy, clicks, whatever, than if I say “X is violence.” That’s part of the reason why if you spend a lot of time on Twitter, you’ll notice that these days it seems like everything is violence. (I also think that in certain rare cases, people — particularly vulnerable ones who spend too much time on social media — fall so deep into some of these rhetorical vortexes and unorthodox belief systems about the nature of harm that they come to really believe they are being violently assaulted whenever someone offends them online.)

But there’s often a broader ideological project at work here, too, I think. Many of the people who push the violent-words trope are in favor of weakening free-speech laws and norms in the U.S., often on the basis of their belief that “free speech” arguments are nothing more than fig leaves for those seeking to defend the powerful against the powerless, and to make life even harder for the latter. If words really were violent, it would be harder to justify free-speech protections, because the same logic underpinning the overwhelming consensus in favor of anti-violence intervention on the part of authorities would apply to at least certain utterances, too.

People are free, of course, to make these arguments about free speech, as silly and self-defeating as I find many of them to be. But language should be as clear as possible. Distinct concepts should remain distinct unless there is a compelling reason to collapse them together. The term ‘violence’ already points to such an important, terrifying part of being alive. Why water it down?

Questions? Comments? Violent words hurled fecklessly? I'm at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal.