Shoddy Research Won’t Help People Who Actually Have Long Covid

On a new PLOS ONE study about “Long Covid stigma”

Long Covid is a little-understood subject. The Centers for Disease Control certainly views it as a real thing, explaining that “Some people who have been infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 can experience long-term effects from their infection, known as post-COVID conditions (PCC) or long COVID.”

But if you read its page on the condition closely, you’ll encounter a bit of shruggery. The list of potential symptoms, for example, includes tiredness or fatigue that interferes with daily life, fever, respiratory and heart symptoms, difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, cough, chest pain, heart palpitations, difficulty thinking or concentrating (“brain fog”), headaches, sleep problems, dizziness when standing up (light-headedness), pins and needles feelings, changes in smell or taste, depression, anxiety, diarrhea, stomach pain, joint or muscle pain, rashes, or changes in menstrual cycles.

It goes without saying that a lot of these symptoms are quite common, and can be explained by any number of conditions. If you get Covid, and then a few months later develop sleep problems and anxiety, does that mean you have long Covid? Who knows? Because we’re so early in our understanding of this condition, the CDC can’t even provide much detail about how long these symptoms last: “People with post-COVID conditions can have a wide range of symptoms that can last more than four weeks or even months after infection. Sometimes the symptoms can even go away or come back again.” I had Covid less than a year ago and I’ve certainly had a number of these symptoms. I definitely don’t think I have long Covid, though.

I’m going to tread carefully when it comes to long Covid because it’s a very fraught subject. Some people think they have it and are very frustrated that they are not taken more seriously, or given more useful advice, by the medical establishment. This is understandable.

But if we don’t know much about a subject, we don’t know much about that subject. We should be particularly careful and methodical about advancing our knowledge of it, rather than leaping to conclusions before much evidence is in.

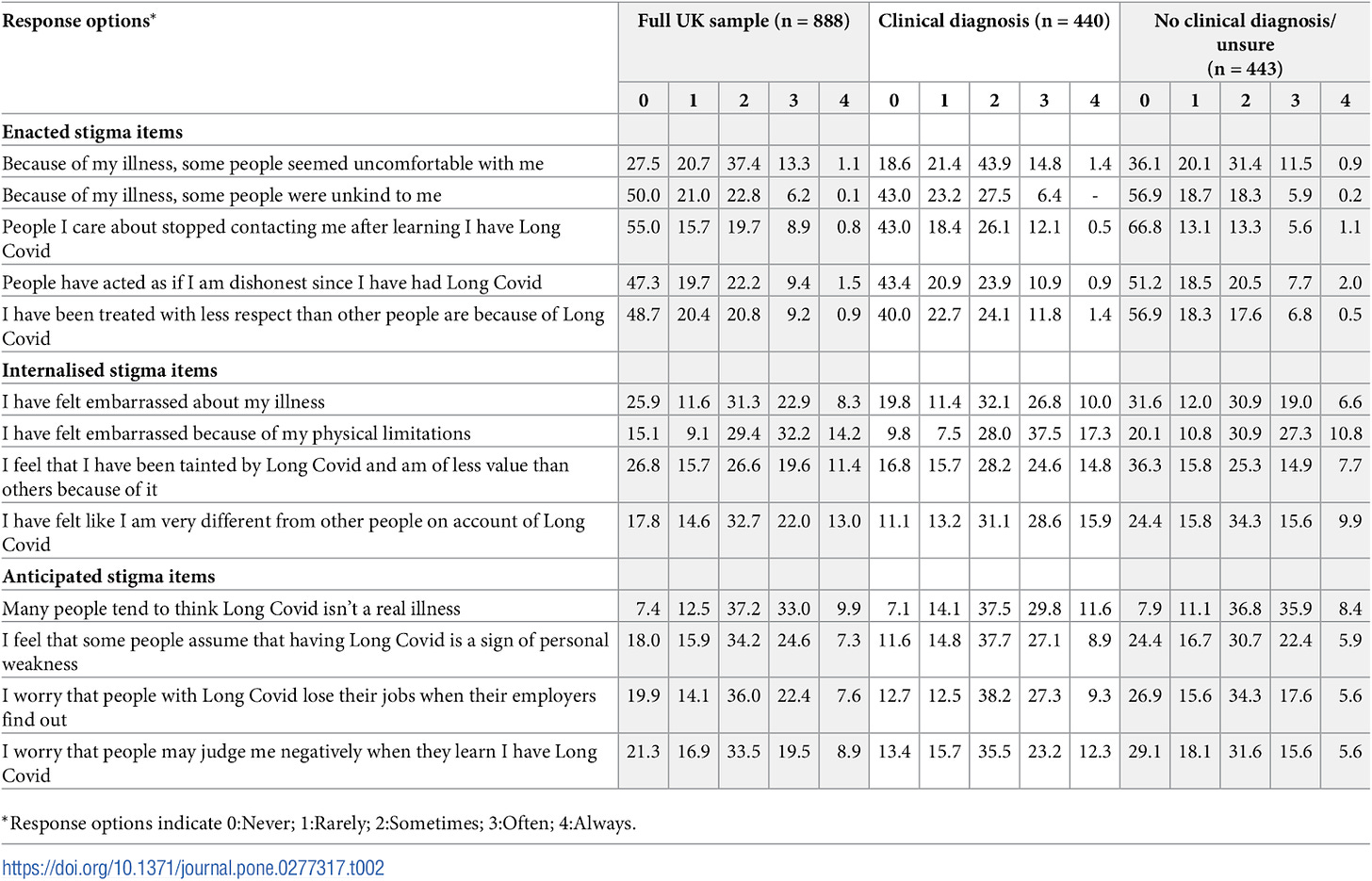

Which brings me to a just-published article in PLOS ONE called “Long Covid stigma: Estimating burden and validating scale in a UK-based sample.” As the name suggests, the researchers — Marija Pantelic, Nida Ziauddeen, Mark Boyes, Margaret E. O’Hara, Claire Hastie, and Nisreen A. Alwan — are seeking to validate a new scale measuring stigma against individuals with long Covid, and to estimate the prevalence of said stigma.

Reading this paper got me thinking about my coursework in psychology. It was somewhat limited — AP Psych, which I loved, and a handful of college courses — but my instructors hammered certain lessons home repeatedly. One is that people are biased judges of their own conditions, or of what will help or harm them. Those courses, and a ton of stuff I read in the years that followed, instilled in me a more general belief that we are all caught in the fog of our own cognition and experience, and that oftentimes this can make it hard for us to make accurate judgments about ourselves. That is why therapists — or, in the case of physical ailments, doctors — are useful. Of course they shouldn’t ignore what we have to say about how we are feeling or doing, but they can also provide useful clarification or context or even pushback, because (in theory, at least) they are the experts.

It’s been interesting to watch some of these understandings get supplanted by new, very different understandings. Science isn’t static — the presumptions that underpin it are ever changing and are subject to the whims of cultural tides. And I wonder, sometimes, about the new way of doing things that at least some researchers have adopted.

In this paper, for example, the researchers rely on a sample of individuals who chose to respond to online surveys about long Covid because they believe they have it. Believe is the operative word because we don’t know if they have it; 50% of them said they were diagnosed with it, but we don’t know if that’s true, either. So this is a very biased sample and the researchers have no idea who actually has long Covid and who has mistakenly or prematurely self-diagnosed themselves.

I feel like if my AP Psych teacher had handed out this paper just a month or two into our first semester and asked what was the major flaw with it, everyone would have shot their hands up to point out that people might not be able to accurately diagnose themselves with a medical condition, and that they also might not be excellent judges of the effect that condition has on how others perceive them.

And yet Forbes reports in a confident headline: “At least 76% Of People Who Have Long Covid Face Stigma Frequently.” That 76% figure is apparently derived from the survey questions in the study, which asked respondents to rate their agreement with statements such as “Because of my illness, some people seemed uncomfortable with me,” and “People I care about stopped contacting me after learning I have Long Covid.”

We’re presuming a lot if we take these claims at face value. We’re presuming the person really has long Covid, for one thing, and then we’re presuming that they are correctly attributing certain events in their life, such as a falling out, to long Covid rather than a host of other factors. To take the most obvious, albeit fraught, possibility, a hypochondriac type might come to be convinced they have long Covid, and become fixated on it, and this could affect their relationships with others. In a situation like that, does it help anyone to chalk up the result to “long Covid stigma,” or is something a bit more complicated going on? And again, this wasn’t a random sample of confirmed coronavirus sufferers, or anything like that — it was folks who responded to a solicitation to fill out an online survey about their long Covid. Even just the sheer out-of-whackness of the gender breakdown (84% female) should give us pause.

The researchers acknowledge none of this. They simply ignore some rather well-established principles of human psychology. Strikingly, they do mention — a couple times — that some of the authors themselves have long Covid. The first sentence under “Strengths and Limitations,” for example, treats this as a strength: “[Their scale] was informed by theory and other stigma scales, co-designed with people with Long Covid and validated in a large UK sample, and takes less than 10 minutes to complete.” They don’t explain why someone with long Covid would be better at developing a long Covid stigma scale than someone without it. I’m not saying this isn’t the case, but couldn’t you see that going in either direction? It’s just a strange bit of identitarianism slipped in without any attempt to defend it, as though anyone reading this will already know why this is an inherent strength. (Of course researchers studying a condition should consult with sufferers on various fronts, but that’s a different claim from the idea that having the condition automatically makes you better qualified to develop a survey instrument.)

Science communication is so often a game of telephone. A lot of people are going to treat this study as solid evidence that stigma against a condition that no one really knows much about is a pervasive societal problem, at least in the UK. This will, of course, boost the researchers’ profiles and spur more research into this fairly niche subject — research that will likely continue to use shoddy methods crippled by unacknowledged confounds. But will any of this actually lead to useful information that will help long Covid sufferers? I’m skeptical.

Questions? Comments? Proof that I have long Covid despite my feverish denials? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Image: “Young woman is looking at the thermometer. She has fever. - stock photo” via Getty.

To muddy the waters even further, most people at this point have had both Covid vaccines and Covid itself. Any lingering symptoms tend to be interpreted politically; some people will say they have Long Covid while others with identical symptoms will say they're suffering adverse side effects of the vaccine.

This “study” is the equivalent of a journalist who wants to offer a certain opinion or interpretation of an event, so goes to a source he or she knows will say the “right” thing, and uses that quote to express said opinion. There are supposed to be checks against that kind of practice in science. Thanks to Jesse for continuing to bring these things to light.