On Scientific Transparency, Researcher Degrees Of Freedom, And That NEJM Study On Youth Gender Medicine (Updated)

There are a lot of unanswered questions here, which is unfortunate

(Update: Part 2 is published here.)

There’s a concept called “researcher degrees of freedom” that is quite important to understanding forms of shoddy science that are less salacious but (far) more common than, say, outright data fraud.

As Joseph P. Simmons, Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn wrote in 2011:

In the course of collecting and analyzing data, researchers have many decisions to make: Should more data be collected? Should some observations be excluded? Which conditions should be combined and which ones compared? Which control variables should be considered? Should specific measures be combined or transformed or both?

It is rare, and sometimes impractical, for researchers to make all these decisions beforehand. Rather, it is common (and accepted practice) for researchers to explore various analytic alternatives, to search for a combination that yields “statistical significance,” and to then report only what “worked.” The problem, of course, is that the likelihood of at least one (of many) analyses producing a falsely positive finding at the 5% level [of confidence that is a common benchmark for statistical significance in the social sciences] is necessarily greater than 5%.

As I put it in my book: “If I sell you a pill on the basis of data showing it reduces blood pressure relative to a control group given a placebo, but fail to tell you that I also tested its efficacy in improving twenty-five other health outcomes and came up empty on all of them, that’s a very weak finding. Statistically, if you have enough data and run enough tests, you can always find something that is, by the standards of the statistical tests psychologists use, ‘significant.’ ”

(Update, 6/20/2023: Back in April, I received an email from an astute observer who pointed out that the example I used here isn’t exactly right in light of what follows. I told him I’d look into it within a couple days and then promptly forgot, and here we are, in June. I’ll simply put the bulk of our email exchange in a footnote so that interested readers can see.1 My correspondent himself describes the difference between what I’m describing in my book and what I lay out in this post as “an incredibly subtle distinction.” After reading his emails and Part 2 of my coverage of this study, you’ll see that nowhere do I quibble with the statistical significance of the variables that did show improvement, so I think this is a fairly technical nitpick, but I don’t want to sweep it under the rug.)

Or, phrased differently, “Torture data long enough and it will confess to anything.” Then, once you get the confession you want, you can HARK, or hypothesize after the results are known — Ah, yes, this is what we expected to find all along. I knew the pill would help fight high blood pressure. In a situation like this, though, there’s a serious risk that what you’re looking at is not a pill that lowers high blood pressure, but statistical noise.

The good news is that there’s a growing awareness among researchers in psychology and other fields affected by replication crises of how these practices can generate weak and non-replicable results. Science reformers have begun constructing guardrails that effectively constrict researchers and reduce their degrees of freedom: For instance, you can incentivize or require researchers to “preregister” their hypotheses and lay out exactly which statistical tests they plan to run, so that if they change their analysis plan or hypothesis midstream, this will be visible for all the world to see. You can also incentivize or require them to share their data, which makes it easier for other researchers to check and see whether they engaged in statistical chicanery.

I think there’s a reasonably strong case to be made that the positive results reported in “Psychosocial Functioning in Transgender Youth after 2 Years of Hormones,” a highly anticipated research paper just published in The New England Journal of Medicine, can be at least partially explained by the sort of statistical cherry-picking that tends to generate wobbly findings.

The NEJM paper is part of the Trans Youth Care–United States (TYCUS) Study, which the researchers describe as “a prospective, observational study evaluating the physical and psychosocial outcomes of medical treatment for gender dysphoria in two distinct cohorts of transgender and nonbinary youth,” one receiving puberty blockers (the team hasn’t reported on those results yet), and another — this one — receiving hormones. The TYCUS study is taking place at four major youth gender clinics: The Center for Transyouth Health and Development at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; the Gender Multispecialty Service at Boston Children’s Hospital; the Child & Adolescent Gender Center Clinic at Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco; and the Gender Identity & Sex Development Program at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. The researchers listed as coauthors on this study include some of the bigger names in youth gender medicine and psychology: Diane Chen, Johnny Berona, Yee-Ming Chan, Diane Ehrensaft, Robert Garofalo, Marco A. Hidalgo, Stephen M. Rosenthal, Amy C. Tishelman, and Johanna Olson-Kennedy. A number of them have been outspoken advocates for youth gender medicine treatments.

This team has received significant sums of grant money to study this population, and for good reason: American gender clinics are very behind in producing useful data that can help us better understand whether and under what circumstances youth gender medicine benefits kids with gender dysphoria. As the authors write in their study protocol, their goal is to “collect critical data on the existing models of care for transgender youth that have been commonly used in clinical settings for close to a decade, although with very limited empirical research to support them.” They wrote that in 2016, but the situation hasn’t really changed: There is almost no good — or even decent — data on these vital questions. On the same page of the protocol they write: “This research is highly significant in scope as it is the first longitudinal study collecting data — assessing both physiologic and mental health outcomes — to evaluate commonly used clinical guidelines for transgender youth in the U.S.”

The researchers’ NEJM study marks the first time they have published data tracking, over time, the mental health of the youth cohort that went on hormones. And the news seems to be good: The team reports that two years following the administration of hormones, the trans kids in their study experienced increases in their appearance congruence, or the sense that their external appearance matches their gender identity, and positive affect. Trans boys (natal females) also experienced reductions in depression and anxiety, and increases in life satisfaction, though trans girls (natal males) didn’t.

On the basis of these findings, the study is being widely touted, both by most mainstream media outlets that have covered it and by the authors themselves, as solid evidence that hormones improve the well-being of trans youth. “Our results provide a strong scientific basis that gender-affirming care is crucial for the psychological well-being of our patients,” said Garofalo, one of the principal investigator for the study, as well as co-director of the youth gender clinic at Lurie Children’s Hospital, in a press release published out by the hospital. “The critical results we report demonstrate the positive psychological impact of gender-affirming hormones for treatment of youth with gender dysphoria,” added Olson-Kennedy, Medical Director of the Children's Hospital Los Angeles clinic.

I disagree with these assessments, but I’ll take that up in a separate Part 2 of my critique of this study, which will focus on the results the researchers reported. This post is mostly about the results they didn’t report, which is an important story in its own right.

My case that something questionable is going on here is simple, and rests largely on the study protocol the authors wrote as part of their Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval process. This document is listed and linked to right there in the supplementary section of their article’s NEJM page:

You can read or download the protocol, the paper, and a supplementary appendix we’ll get to later here if you want.

The protocol is a long, rich document, and among other information it lays out the study procedures for both the hormones and the blockers cohorts. There’s a note in the supplementary section of the document explaining that it includes both the “original” (2016) and “final” versions of the protocol. I’ll quote from the final and therefore more applicable version, which was submitted May 11, 2021, though when it comes to what I’m about to discuss, there aren’t substantive differences between the two versions (with one exception I’ll get to).

The protocol document acts as a de facto preregistration for Chen and her team (they also published a shorter version of it as a Registered Report, a form of more official preregistration), and it shows that in the NEJM study, the researchers simply excluded most of the key variables they had hypothesized would improve as a result of hormones, and that they changed their hypothesis significantly, in a manner that shunts some of those variables off to the side.

Let’s get specific about what the authors did and why it raises questions. They list a number of hypotheses in their protocol document. One of them fits the current study: “Hypothesis 2a: Patients treated with gender-affirming hormones will exhibit decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression, gender dysphoria, self-injury, trauma symptoms, and suicidality and increase [sic] body esteem and quality of life over time.”

The first subsection of their “Statistical Analysis” section is headed “Primary Objective: Effects of Hormonal Interventions on Mental Health and Psychological Well-Being,” and there the authors explain that their analysis “will investigate the changes over time in gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, self-injury, suicidality, body esteem, and quality of life.” So it’s pretty clear, between the hypothesis and this primary objective bit, what they were most interested in investigating.

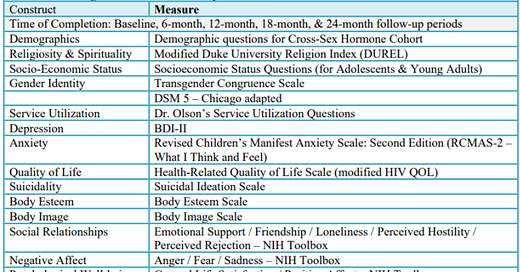

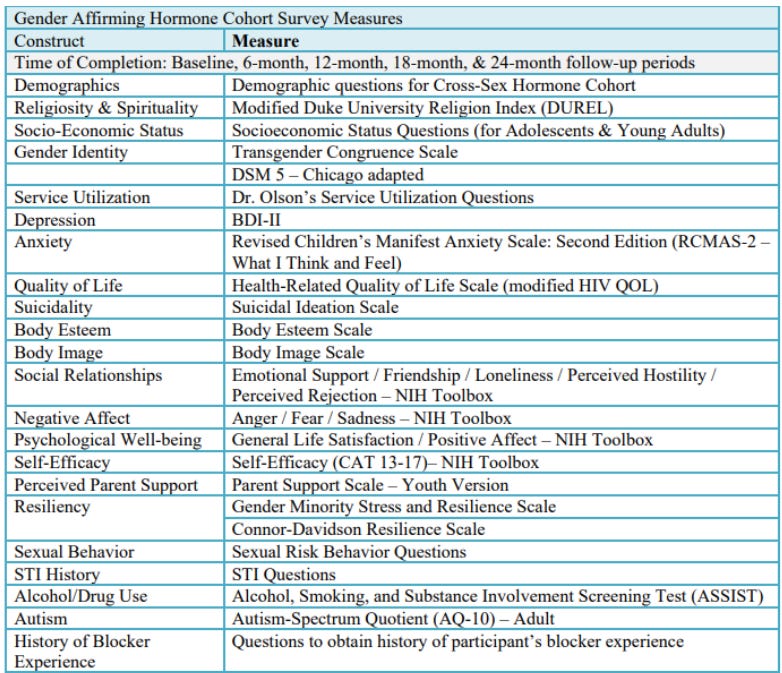

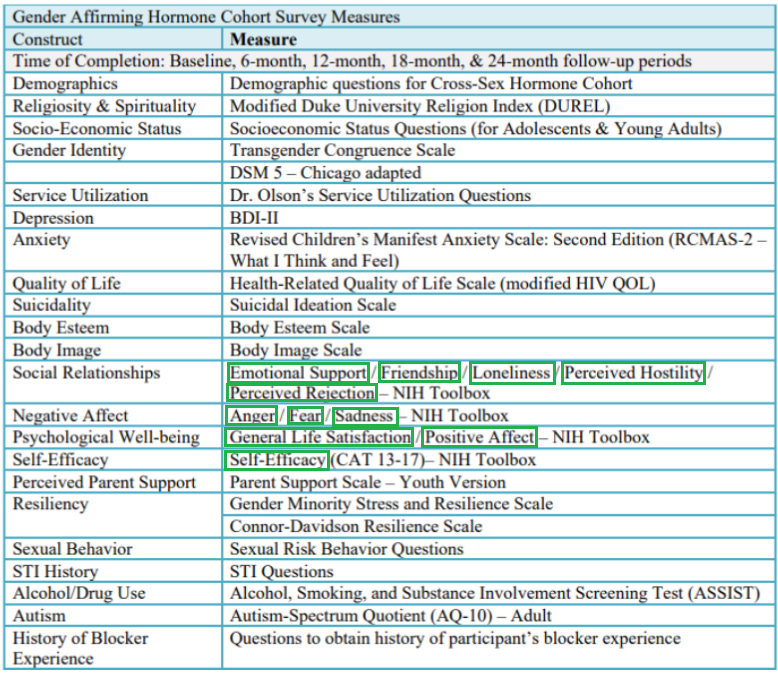

In Appendix II of the protocol document the researchers include a helpful chart of the instruments they plan on using to track these and other variables. It’s a bit out of date, though, as it still uses “cross-sex hormones” rather than “gender-affirming hormones” and includes a couple of variables that the researchers subsequently dropped. A more up-to-date version is downloadable here, and here’s the part of it listing all the variables for which data was collected at every six-month wave of the research effort (that’s the data the researchers would be most likely to report on in a big study):

Okay, now let’s jump to the “Measures” section of the present study in NEJM, where the researchers list their variables: “With respect to longitudinal outcomes, participants completed the Transgender Congruence Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory–II, the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Second Edition), and the Positive Affect and Life Satisfaction measures from the NIH (National Institutes of Health) Toolbox Emotion Battery at each study visit.”

If you compare that to the protocol document, you’ll notice that of the eight key variables the researchers were most interested in — “gender dysphoria, depression, anxiety, trauma symptoms, self-injury, suicidality, body esteem, and quality of life” — the ones I bolded are not reported in the NEJM paper. That’s six out of eight, or 75% of the variables covered by the researchers’ hypothesis in their protocol document (including the “officially” preregistered shorter version).2

In fact, most of these variables aren’t mentioned at all in the NEJM paper or its supplementary appendix. “Gender dysphoria” comes up early, because how could it not in a paper about, well, gender dysphoria, but there’s no mention at all of any gender dysphoria scale (this is the one missing variable they have a partial but non-exculpatory explanation for, which I’ll get to). Neither the phrase “quality of life” nor any mention of the Health-Related Quality of Life Scale appear in the paper. The authors do report on the number of completed suicides and instances of suicidal ideation in the sample (more on that in Part 2), but there’s zero mention of the suicidality scale — the one they reported on in the baseline characteristics paper — that would allow them to statistically analyze the sample’s level of suicidality over time the way they analyze other variables’ longitudinal trajectories. (They definitely have data on body esteem and suicidality, at least, because they report the baseline numbers for these variables in a 2021 paper.)

I checked the NEJM article’s supplementary appendix, too, to see if there’s any explanation for the disappearances there. I came across a very promising short section subheadlined “Rationale for Selecting Primary Mental Health Outcome Measures,” but alas, it concerns a relatively minor and unrelated issue — it doesn’t actually explain where their key variables went. Those variables go unmentioned in the rest of this appendix as well. (If the authors wanted to explain the absence of certain variables without taking up potentially limited space in the paper itself, this would have been a good place to do so.)

The researchers’ hypothesis changes in the NEJM study, too. To be fair, when they reference their hypothesis here it’s in a less formal and more colloquial way — there’s no official Hypotheses section like there is in the protocol document. But still, look at this shift:

Hypothesis from the latest version of protocol, published in 2021: “Patients treated with gender-affirming hormones will exhibit decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression, gender dysphoria, self-injury, trauma symptoms, and suicidality and increase [sic] body esteem and quality of life over time.”

Hypothesis from the NEJM study, published in 2023: “We hypothesized that [after kids were administered hormones], appearance congruence, positive affect, and life satisfaction would increase and that depression and anxiety symptoms would decrease. We also hypothesized that improvements would be secondary to treatment for gender dysphoria, such that increasing appearance congruence would be associated with concurrent improvements in psychosocial outcomes.”

There’s some similarity, in that depression and anxiety are mentioned in both instances, but the changes are rather striking. Out are a number of the variables they originally hypothesized would be most important, including several — GD, suicidality, and self-harm — universally recognized by youth gender researchers as vitally important. In are some other variables, like “appearance congruence, positive affect, and life satisfaction,” that, yes, were included in the original protocol document, but which weren’t treated as particularly important, failing to garner mentions in the hypothesis or primary objective sections. (And no, quality of life and life satisfaction are not the same construct — they’re listed under two different variables in the study protocol, and there’s at least one study out there attempting to evaluate the strength of the correlation between the two.)

In the NEJM paper, the researchers appear to be much more interested in the concept of “appearance congruence” than they were previously. While the vital terms suicide (and its variants) and dysphoria are mentioned eight and nine times, respectively, in the paper…

…“appearance congruence” gets mentioned 52 times.

It even comes up in the very first paragraph: “An important goal of such treatment is to attenuate gender dysphoria by increasing appearance congruence — that is, the degree to which youth experience alignment between their gender and their physical appearance.”

I mean, maybe? But again, the shift in emphasis is noteworthy. The phrase appearance congruence doesn’t get mentioned once in the protocol document, and the only time the word appearance turns up in this context, it’s in this description of the Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS), one of the variables the researchers collected data on: “A construct of congruence to conceptualize the degree to which transgender individuals feel genuine, authentic, and comfortable with their gender identity and external appearance.”

Even here, there’s apparent cherry-picking. In both the protocol document and the NEJM paper, the authors mention administering the TCS. But they don’t report the full results anywhere in the NEJM paper — instead, they report on only one of the scale’s two subscales, Appearance Congruence (again, we know they have the full data because they provided some of it in their baseline measures paper). This means the researchers had three bites at the apple: They could analyze the changes over time on the full scale, and then each of the two subscales. They report on only one of these three results, and this nets them what they describe in the paper as their strongest finding: Over the course of their two years on hormones, the average kid in the study improved about one point on this five-point subscale. The researchers then build a significant chunk of their paper around this finding, going so far as to say they hypothesized that appearance congruence would be important — which, to me, reads as though they hypothesized it all along, when I’m not seeing any evidence they did. Rather, they hypothesized something pretty different in their protocol document, and then they changed that hypothesis without explaining why. (I also think this finding about appearance congruence is far less impressive than the researchers are making it out to be, but I’ll leave that for Part 2.)

There’s something a bit similar going on in the researchers’ approach to the NIH Toolbox, “a multidimensional set of brief measures assessing cognitive, emotional, motor and sensory function from ages 3 to 85.” It’s basically a buffet of different survey items (more info and scoring scales here) — there are a lot of them. If I pull that big table back up and indicate the different items the researchers included from this battery…

…you’ll see that the researchers had participants in the study fill out NIH Toolbox items on Emotional Support, Friendship, Loneliness, Perceived Hostility, Perceived Rejection, Anger, Fear, Sadness, General Life Satisfaction, Positive Affect, and Self-Efficacy.

None of these items were emphasized by the researchers in their original hypothesis or primary objective section, so we probably shouldn’t have any prior belief about which ones we should expect them to report in a major study, but still: Nine of the 11 are nowhere to be found, leaving us with only Positive Affect and Life Satisfaction measures. Why? And why was it more important to report on “Life Satisfaction,” not listed in the hypothesis or primary outcomes sections, than it was to report on “Quality of Life,” which was? For that matter, why report on the Positive Affect but not the Negative Affect items? If hormones help kids feel better, shouldn’t they experience less anger, less fear, and less sadness over time?

We have a lot of useful information about the researchers’ protocol thanks to what they’ve posted online. They definitely needed to submit their protocol document for IRB approval and have it on file somewhere, but I’m a bit of an ignoramus about all this bureaucratic stuff, so I don’t know if they were obligated to post it publicly as a grant requirement or an NEJM requirement, or if they did so out of a spirit of openness. Either way, the existence of the protocol document nicely demonstrates why this sort of scientific transparency is helpful: In this case, it allows us to go beyond the officially published results, to compare those results to the broader process that produced them, and to ask questions. What’s less helpful is the lack of any sort of information about why the authors made the choices they made for the NEJM paper.

It should go without saying that I’m not arguing that if hormones have a beneficial effect on trans youth, every variable in this study should exhibit a large and salutary change. My point is that because there’s no explanation, we can only speculate as to how the researchers made all these subtle decisions — decisions that allowed them to write, in their final published article, that “there were significant within-participant changes over time for all psychosocial outcomes in hypothesized directions.” This is borderline misleading. By “all” psychosocial outcomes, they don’t mean all the ones they measured and evaluated for change over time — they mean the ones they chose to report results on. Which might render their findings totally trivial. To take a more extreme example, I can’t flip a coin over and over and over, until I finally get 10 heads in a row hours later, and then write “The presence of 10 heads in a row suggests the coin is not fair.”

So why did so many of the variables disappear? There are a few possibilities. One is that the researchers plan on reporting on these outcomes in an upcoming study, though I’m not sure why they would hold back from the NEJM, and this still wouldn’t explain how they chose which variables to report. Another possibility is that the journal itself asked the researchers to focus on specific variables. The path to getting a paper published in a journal as prestigious as NEJM can be a bruising one, and you might submit a first draft that you’re very excited about, because of what it shows about A and B and C, only to have the peer reviewers butcher your beautiful baby until, many months or even years (not to mention gray hairs) later, you resignedly sigh and agree to publish a paper with much less exciting, severely hedged findings pertaining to the far less sexy variables X, Y, and Z. I guess that could have happened here, but it would just kick that can of “Why did you go with these particular variables?” over to the NEJM, meaning the serious methodological questions would remain unanswered. Also, as we’ll see in Part 2, the NEJM didn’t exactly crack the whip when it came to this paper’s methodological tightness, so I’m not sure how much I buy this hypothetical version of events.

Overall, if I had to guess, I think the most likely explanation here is that the researchers did a lot of “exploratory analysis” until they found reasonably impressive-seeming results, and then chose to refocus their efforts — and to rejigger their hypothesis — around those results, tossing some disappointing results in a file drawer. If I’m right, this wasn’t necessarily an intentional process on their part. When you have a lot of people poking around in a lot of data without certain guardrails in place, it’s easy to lose track of all those unsuccessful statistical tests you ran while remembering the positive results that do support your preferred hypothesis. But regardless of whether I’m correct and whether any potential cherrypicking here was intentional, the researchers should have at least realized what was missing from their NEJM paper and explained what happened somewhere.

But all I can do is speculate, because they won’t answer any questions about their process, or about the possibility of sharing their data so others can investigate these issues. I sent specific questions to the NEJM, to press contacts at two of the universities, and to four members of the team (Chen, Hidalgo, Rosenthal, and Tishelman), and other than a response from NEJM saying I should reach out to the researchers' institutions directly, I only heard back from a Lurie Children’s Hospital press person confirming the researchers weren't doing any interviews. To be fair, the no-interviews stance appears to be consistent, regardless of the journalist who asks. My last email asked that press person if the team could share their data — she said she'd check but I haven't heard back. (I’m actually not sure how data-sharing works here — their protocol document notes that the team will eventually share it with other National Institutes of Health researchers,3 but it could be that they face restrictions when it comes to random journalists or independent academics. So an unwillingness to share data isn’t necessarily grounds for suspicion in this case.)

This refusal to talk to journalists is an unfortunate decision on the researchers’ part, especially when paired with their glowing quotes about the importance of their findings — quotes that obscure a lot of nuance and missing results. At the end of the day, this team publicly predicted that eight variables would move in a particular direction. Then, when it was time to report their data, they only told us what happened to two of those variables, and the two they did report weren’t even direct hits, given that trans girls didn’t experience reductions in depression and anxiety. If these findings are so impressive, where are all those other variables?*

***

I believe the seminal article on HARKing, or hypothesizing after the results are known, is this 1998 one published by Norbert L. Kerr in Personality and Social Psychology Review. At the time, this wasn’t a well-known phenomenon, and some people actually argued for it! The idea was that if in poking around your data you uncovered a new explanation, why not update your hypothesis to account for it? Many otherwise talented and good-hearted researchers didn’t really understand the statistical and other downsides to this back then, so Kerr had to actually, affirmatively argue that the cons of HARKing outweigh the pros. In that sense it’s a strange read by present standards — these days most researchers understand why these practices lead to shaky science.

Kerr writes:

Probably everyone would agree that, all other things being equal, “good” (i.e., clear, coherent, engaging, exciting) scientific writing is better than “bad” (i.e., incoherent, unclear, turgid, unengaging) scientific writing. But everyone would also probably acknowledge that an author of a scientific report has constraints on what he or she can write under the guise of telling a good story. Scientific reports are not fiction, and a scientist operates under different constraints than the fiction writer. No matter how much the addition might improve the story, the scientist cannot fabricate or distort empirical results. The ultimate question is whether any such constraints should apply to the fictional aspects of HARKing (e.g., inaccurately representing certain hypotheses as those hypotheses that guided the design of the study).

Did the NEJM article’s authors “inaccurately represent[] certain hypotheses as those hypotheses that guided the design of the study”? Maybe this is too strong a claim, but I’m not sure. The researchers are crystal clear about the variables they are most interested in in the protocol document that supposedly underpins this study — they hypothesize that “Patients treated with cross-sex hormones will exhibit decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression, gender dysphoria, self-injury, trauma symptoms, and suicidality and increase [sic] body esteem and quality of life over time.” Then, in the study that is one of the main reasons they were collecting all this data in the first place — a study that includes the line “The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol” — their hypothesis is substantially different, and they present their interest in appearance congruence as a hypothesis they had all along, when there’s no evidence that was the case. This change, and the disappearance of all these variables, go almost entirely unexplained.

As I alluded to earlier, the authors do offer a partial explanation for the absence of gender dysphoria variables. Originally, they collected GD data using two instruments, the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS) and the Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults (GIDYQ-AA). In a 2019 article in Transgender Health, they write about some of the ostensible flaws with these measures and explain that they stopped collecting data on them:

The necessity for an improved measure to capture the nuanced elements of gender dysphoria and its potential for intensification or mitigation over time has been highlighted by our transgender team members who have been on the front line with youth participating in the study. After significant deliberation, we chose to include the UGDS in this study, in the hopes that we might demonstrate its limitations in capturing the dynamic experience of youth with gender dysphoria. For similar reasons, we also included The Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults (GIGDQAA) [GIDYQ-AA].

Over the course of the past 2 years, there were concerns articulated by participants regarding distress they experience when confronted with some of the items from both of these instruments. A decision was made to remove the UGDS and GIGDQAA [GIDYQ-AA] from the participant assessments, except for those participants completing a substudy to obtain participant feedback regarding items included in those two scales. Our team felt that the Transgender Congruence Scale and the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Scale are likely the best existing measures to collect information about both distal and proximal drivers of gender dysphoria. [footnotes omitted]

I found this a little strange — they used these two GD scales not to measure GD, as their protocol document explains, but because they thought they were bad and wanted to demonstrate that? Setting that aside, this does check out, as the protocol document includes a 2019 “Letter of Amendment” removing those two instruments. (They’re still administered at the 24-month visit.)

But if the Transgender Congruence Scale and the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Scale are, in fact, “likely the best existing measures” to evaluate gender dysphoria, why are they both missing from the NEJM article, other than that one TCS subscale? And according to the protocol, the kids in this cohort were also asked about their DSM-5 gender dysphoria symptoms until a separate 2021 Letter of Amendment halted that question. But that data, too, is absent from the NEJM paper. Why?

So, long story short, whether the abandonment of the UGDS and GIDYQ-AA was justified, the researchers did collect data on three other measures that they believe serve a similar purpose, but then didn’t publish it. It’s disappointing that this study offers no data on GD, given that alleviating GD is the ostensible medical justification for putting kids on blockers and/or hormones in the first place despite the lack of solid published evidence about these treatments.4 It would be interesting to know whether any peer reviewers or NEJM editors asked the authors why their paper lacked longitudinal data on gender dysphoria, suicidality, and self-harm given the importance of these variables, and given the research team’s demonstrated prior interest in monitoring these outcomes.

Nothing I’m saying about researcher degrees of freedom or HARKing is new or controversial. Again, researchers have known for years that you really can’t do this — if you don’t account for the fact that you made a bunch of other statistical comparisons you didn’t report on, it might call your entire analysis into question, because results that appear to be statistically significant can be pushed under that threshold once you make the appropriate corrections.

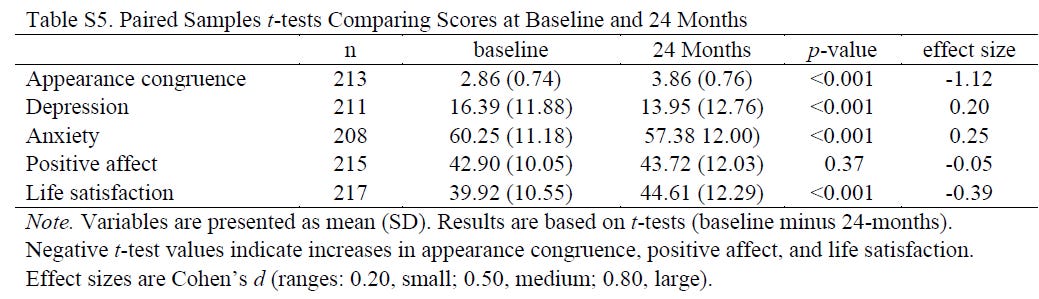

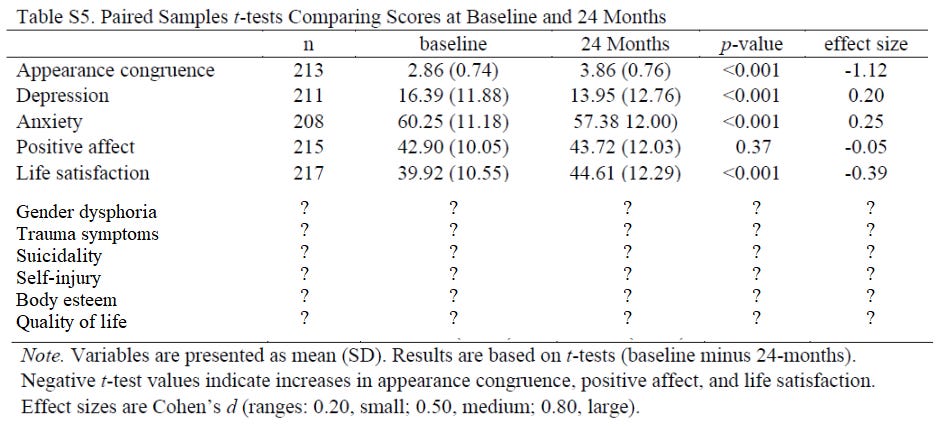

Here’s a handy table from the supplementary appendix running down the average scores on the five variables the researchers reported at baseline and 24 months (the final wave of data collection for this study):

Setting aside various issues that I will get to in Part 2, such as the fact that the researchers are touting a two-year increase of 0.82 points on a 100-point Positive Affect scale as evidence that hormones work, there’s so much missing from this.

Really — if you’ll excuse my truly dismal MS Paint skills — the chart should look something like this:

And that’s just the variables the researchers mentioned in their hypothesis; they saw fit to pick and choose from all those other variables, too, so really we could make a much, much longer version of this chart with many more question marks.

If you fill in those question marks, are the researchers still able to hail their study as an impressive finding? The whole reason you’re supposed to communicate in a clear, transparent manner about your methodological choices is to prevent critics from being able to ask such questions in the first place. The fact that all of this is up in the air should be seen as a shortcoming on the part of the authors, the journal, or both.

Or, to put it another way: Let’s do a visualization of the outcomes they did report, out of all the outcomes they could have reported:

The point is, however you phrase it or visualize it, the researchers explain so little about their process, about the path from their original study protocol to this finished product — an article in one of the top research journals in the world — that until they fill in some of these gaps, I can’t help but be skeptical. And I think you should be too.

Questions? Comments? Evaluations of this newsletter that suffer from myriad methodological shortcomings? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

*correction: In this paragraph, I originally said that the researchers revealed the results of six of their variables. The correct figure here is two, so I fixed it. Thanks to the attentive commenters who noticed this error.

His original email ([sic] throughout, his emails and mine):

Hi,

My name is [redacted], and I’m a statistics PhD student currently in my 4th year of study. My research focuses on causality within the point process framework (not that that’s helpful here but regardless). I’m writing to offer a slight critique of this article. There’s some statistical errors that I think should be addressed.

You state this:

“If I sell you a pill on the basis of data showing it reduces blood pressure relative to a control group given a placebo, but fail to tell you that I also tested its efficacy in improving twenty-five other health outcomes and came up empty on all of them, that’s a very weak finding. Statistically, if you have enough data and run enough tests, you can always find something that is, by the standards of the statistical tests psychologists use, ‘significant.’ ”

This is, obviously, a correct statement. You are describing, as I’m sure you’re aware, what’s usually referred to as p-hacking. I want to explain why the case you discuss within this article is not relevant to this issue.

What is the problem with p-hacking? As I’m sure you’re aware, the issue lies in the fact that when performing hypothesis tests, the significance level is the value for the proportion of “false positives” that you are satisfied to observe. The problem is that when you perform multiple hypothesis tests, the probability of a false positive increases, since even with two tests being done now the probability of one false positive will be (assuming a 5% significance level) (2)(.95)(.05) + (.05)^2 > .05.

The solution to this is to divide the significance level you have (for example, .05) by the number of tests you are performing, and use that as your new significance level (this is called the Bonferroni correction). This is why it’s not appropriate to state you will only observe 1 variable, then observe 25 and report out only the significant one—the chance of a false positive is incredibly high.

The issue I have within this is that this is the exact opposite of what this paper did—they actually stated they were going to study more variables, and then cut the number of variables down. I know this is a subtle distinction, but stating you’ll observe 1 variable then observing 25 and reporting one is actually different than stating you’ll observe k variables, observing k variables, but only reporting on 4. In fact, there is an error within their analysis, but it’s not the one that you believe to be true (and it doesn’t affect the paper in the way you think it will). The proper procedure to show that you have achieved significance of your variables without risking an increased false positive rate when you have stated you’ll observe k variables is to perform a Bonferroni correction on the significance level. You’ll notice within the supplement that the p-value for all the variables included within this paper had a p-value well lower than even .05/50, so even if they had stated they were going to observe k=50 variables, it would still be correct to state that the variables they did observe as significant are truly significant.

You’ll notice they didn’t actually do this step—as I suspect they weren’t aware [of] its proper procedure, so that is the error within this paper.

Just to be clear, this is why your accusation of cherry picking variables for false positives is not correct. The removal of variables could mean either:

1) They are actively hiding a significantly negative results or

2) They are excluding insignificant results

NOT that they performed p-hacking to report variables as significant when that isn’t an appropriate statement to make. This is, from my understanding, what you were stating when you provided the pill example, and I hope I’ve made it clear why that is not an appropriate comparison.

Thanks and let me know if you have any questions,

[redacted]

My response:

Thanks for the email, [redacted] — I think I’ll need to at least update the piece to account for that Bonferroni correction issue. On this: “The issue I have within this is that this is the exact opposite of what this paper did—they actually stated they were going to study more variables, and then cut the number of variables down.” What do you mean when you say they stated they were going to study more variables? Just want to make sure I’m getting this. My understanding/claim is that they preregistered a hypothesis dealing with a number of variables, collected data on those variables and other variables, but then published a paper ignoring the original statistical comparisons of interest in favor of (presumably) cherry-picked ones that pointed in the direction they wanted. If I have that right, it could both be true that the results they did report would remain significant post-Bonferroni correction (meaning simply they went up/down a significant degree between t = 0 and t = 1 — the causal questions still remain), but also that the unreported results are a problem that point to the possibility that when it came to the variables they professed interest in, they didn’t see what they wanted to see. Right?

His response to my response:

Hi,

“but also that the unreported results are a problem that point to the possibility that when it came to the variables they professed interest in, they didn’t see what they wanted to see. Right?”

Yes, that’s exactly correct. I know it’s an incredibly subtle distinction, but the problem is either that they could be potentially hiding either not significant results (which is an issue) or results that are significantly negative (which is much more of an issue). There’s also a chance that the inference conditions were not met for a paired t-test as well as a possibility of non-inclusion of the variables (which, while it should have been stated, isn’t an ethical issue).

The correction I think is relevant is that neither of these disrupts the significance of the variables that they did observe, which is how I read your piece to imply, especially with the opening pill example (if I’m reading your work wrong I apologize).

Thanks so much,

[redacted]

A couple too-in-the-weeds notes about these variables: It’s unclear, from the protocol, what instrument the researchers used to measure trauma symptoms, but I’m not seeing any sign it was covered by the variables included in the NEJM study. Either way, the term trauma doesn’t come up in the paper, so it does go unreported. Also, “self-injury” and “suicidality” are indeed separate variables. In their protocol, the researchers mention “Self-Harm – Questions about if and where participant has purposefully harmed themselves” separately from the suicidal ideation scale. So that’s how I got to my count of eight variables.

From the protocol document: “Data will be made available to other NIH investigators under the data-sharing agreement with [Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development] after a reasonable time period that includes enough opportunity to prepare and have submitted for publication four manuscripts presenting the basic outcomes of the project. Beginning in Year 3, peer-reviewed publications will be developed pertaining to cross-sectional hypotheses and research questions found in primary and secondary objectives, though the bulk of publications are longitudinal in nature and will be developed in Year 5. Dissemination of findings to State and County officials, policy makers, and organizations will begin in Year 3, when preliminary data become available.” In the study itself, the authors also note: “There were no agreements regarding confidentiality of the data among the sponsor (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development), the authors, and the participating institutions.”

I guess someone could say “That’s not fair — they did at least publish those Appearance Congruence subscale results.” But that isn’t a validated measure of gender dysphoria, a phenomenon that goes well beyond discomfort with one’s appearance.

I'm the parent of a child who had severe gender dysphoria of the ROGD variety. We didn't go down the affirmation path and his dysphoria has been gone for almost two years.

Having gone down the rabbit hole deep on this topic, here's something obvious to me. Most of the adolescents showing up at gender clinics are dealing with other traumas: not fitting in at school, grossed out by puberty, unable to connect to people because they're autistic. Around ages 13 to 15 are the worst years for these kids. Of course they're depressed and that pain shows up in many ways.

The ones that actually get to a doctor in a clinic are most likely going through a rough patch when they get there. Most of them will feel better after two years of some treatment or no treatment just because they grow up a little and find some friends or a tribe to hang out with.

Any study that says trans kids feel better after two years with transitioning needs a really strong control group. The "feel better" effect of just being 16 instead of 14 is huge.

It is right to be skeptical of science when it has an agenda. For all these gender clinics who've been doing what they've been doing to kids for so many years, they absolutely must prove that they're helping, and helping a lot. It's more than just their jobs at stake.

Well and clearly written! This is a difficult concept to get across, as you and Kerr have discovered. The coin flipping example was good, but I wonder if there's another example that could be given that focuses more on 'torturing the data'.

Possible XKCD example? https://xkcd.com/882/

I'm looking forward to part 2, which I'm guessing will use the word Testosterone (or T) at least 20 times.