No-Platforming Didn’t Wreck Milo — *Milo* Wrecked Milo

Revisionist accounts of the Yiannopocalypse help no one

(A file photograph of Milo Yiannopoulos)

If You Label Me, You Negate Me

In response to yesterday’s thoughts on the Intellectual Dark Web and Intellectual Lite Web and so on, a reader named Daniel wrote in to say, “Your comments on the IDW and unofficial journalist groups in general got me thinking about the utility of using these labels. I think it resembles a signaling model. Writers incur some cost in order to convey non-obvious information about themselves (and on the internet, everything is non-obvious because everyone everywhere is acting in and therefore assuming perpetual bad faith) that helps readers differentiate between writers.”

I think there’s something to this. Though I also think there’s a simpler reason people like and generate these labels: There’s a ton of information out there and our brains latch onto stuff that keeps the world organized. But yes, these labels can certainly serve as useful heuristics — if I hear someone is a member of “weird Twitter,” I can safely assume they have leftist politics and a certain very-hard-to-describe sense of humor that I will definitely know when I see. A “classical liberal” will likely have strong feelings about freedom of speech (pro) and political correctness (not a fan). And so on.

What I was trying to get at yesterday when I said I don’t mind the label progressive but am not interested in anything spicier or more specific is that I don’t feel particularly hemmed in by it. The aspects of my ideology progressive points to are pretty vanilla, having to do with things like my stances on redistribution (more, please) and incarceration (less, please). Within that label I have plenty of room to maneuver — if a specific plan that would increase overall redistribution struck me as ill-conceived, it wouldn’t feel like a threat to my politics to point that out. My worry is that when writers or thinkers decide they belong to more tightly defined clubs than that, the club-membership comes to be a bigger and bigger part of their identity and it introduces forms of bias and ideological pressure that might not be there otherwise. I don’t want that.

People Are Taking the Wrong Lessons from Milos Yiannopoulos’ Swift and Spectacular Downfall

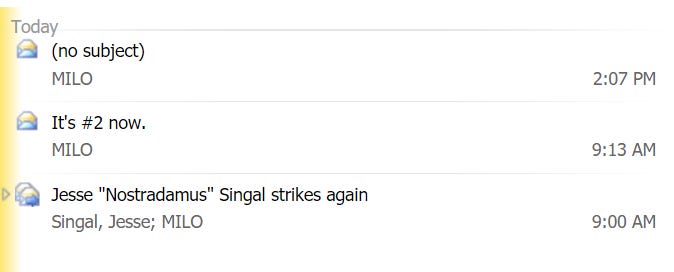

A couple days ago I came across someone I like and respect and know in real life arguing that the fall of Milo Yiannopoulos is proof that no-platforming “works,” at least sometimes. Then I realized that I had more or less missed a Vox article by the (generally!) very smart and sharp Zack Beauchamp making a similar argument last month. Indeed, if you click around you’ll see that this claim, that it was no-platforming killed the beast, has hardened, through repetition, into the status of fact among generally pro-no-platforming liberals and leftists. But the actual facts on this one are pretty straightforward, and they suggest that Milo Yiannopoulos himself, not his no-platforming, was the primary catalyst of the Yiannopocalypse.

Those who followed his career may recall that Yiannopoulos benefited greatly from feeding fodder into the right-wing “Lookit that triggered lib!” machine by being ostentatiously outrageous and offensive.

Here’s how it works: Yiannopoulos goes to a college. He says dumb and offensive trolly things. Students react with outrage and sadness, either during the talk itself or in gatherings afterward. Inevitably, some of them either freak out or burst into tears, because college students are college students. Breitbart and other right-wing outlets then trawl for student-paper coverage, footage of angry students, or both, and then cover these reactions as “proof” that everything Yiannopoulos says about colleges and modern society — something something free-speech SJWs feminazis lesbians — is true.

The attempted no-platformings and (more rarely) violence associated with Yiannopoulos’s campus appearances only accelerated this cycle. Back then Yiannopoulos worked for Breitbart and had the billionaire Republican donor Robert Mercer as a patron, and the idea that Breitbart or Mercer thought “triggered” students or no-platformings or even violence at Yiannopoulos events were bad, rather than a tasty treat delivered from the heavens to help them pump up Yiannopoulos's brand and far-right content in general, doesn’t make sense.

So why did his career collapse? First, in early 2017 a Republican Twitter account surfaced comments in which Yiannopoulos said that sexual relationships “between younger boys and older men… can be hugely positive experiences.” All that misogynistic, anti-Muslim, anti-trans, and other disgusting stuff was totally fine for Breitbart and many of Yiannopoulos’ other enablers, but this was a bridge too far. And it’s clear that it directly sparked the beginning of the end for Yiannopoulos. “The effect was like nothing previously seen in the aftermath of controversial comments from the right-wing provocateur,” Business Insider reported at the time. “Yiannopoulos lost his keynote-speaking slot at the Conservative Political Action Conference. He saw his lucrative book deal canceled. And he resigned as senior editor at Breitbart News.” (I will never forget, prior to all this happening, Yiannopoulos sending multiple gloating emails to my New York email account notifying me of his book’s preorder progress up the Amazon charts after I had written that his exile from Twitter seemed to have hurt his brand, at least based on Google search trends.)

Then, in October of 2017, Joe Bernstein — a journalist at BuzzFeed whose talents I’m genuinely jealous of — reported on the existence of a tranche of documents he had obtained which showed that Yiannopoulos, in the process of co-authoring a long Breitbart article that sought to soften the image of the alt-right and downplay its deeply racist and anti-Semitic roots, had directly solicited the input of, and closely integrated the suggestions of, a “neo-Nazi and a white nationalist” and various other deeply unsavory figures. And that was that for his most important remaining backers: A month later, Rosie Gray of The Atlantic reported that Mercer had announced in a letter to the employees of his investment fund that he was “stepping down from his hedge fund and selling his stake in Breitbart News to his daughters,” and disavowing Yiannopoulos. “I was mistaken to have supported him, and for several weeks have been in the process of severing all ties with him,” wrote Mercer.

It’s genuinely unclear where Yiannopoulos would be right now if he hadn’t been dumb enough to make those remarks about adult-child sex, to solicit direct editorial input from a literal neo-Nazi, and to allow the emails showing he had done so to get leaked to the press. I can’t prove it, but I think that the no-platforming wouldn’t have tripped him up one bit, that it would have only helped his brand, as it had in the past.

Others are free to argue otherwise, but at the very least, those drawing a causal connection between Yiannopoulos’ no-platformings and his precipitous fall have an uphill battle ahead of them if they want to explain away the possibility that the above blunders are its true primary causes. The revisionism taking root in some quarters, which backgrounds those blunders in order to present a cleaner, more pat storyline in which Yiannopoulos was raging unchecked until campus activists banded together and ended his career, doesn’t help anyone who wants to gain a better genuine understanding of the circumstances under which no-platforming might be useful and justified. I’m not a fan of no-platforming myself, but setting that aside we should debate the tactic on its actual merits, not on the basis of the fantasy that it took down a guy whose career was so clearly ended by his own repeated, reckless acts of Sideshow Bob-ery.

Questions? Comments? No-platforming threats? Pride-goeth-before-a-fall emails? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal.