Mainstream Media Outlets Keep Botching Their Coverage Of The Critical Race Theory Debate (Updated) (Unlocked)

A lot of these laws are bad, but we need to have a shared, reality-based understanding of what's actually in them

(Unlocking today, 7/2/2022. Originally posted here.)

This anti-critical-race-theory movement is getting out of control. Really out of control. To the point where, in Wisconsin, right-wing state legislators are seeking to ban an entire list of words from public-school curricula. They literally don’t want kids to have the terms they need to accurately describe the unjust country they see around them!

That, at least, is the dark message you’d have received if you read Slate, Esquire, The Hill, or Scientific American this past fall. And it’s just plain incorrect — part of a growing problem mainstream outlets have accurately conveying the actual, real-life content of the recent spate of bills attempting to ‘ban’ “critical race theory” from schools.

You may have noticed those scare quotes. These bills are all over the place, and they often don’t actually come close to banning critical race theory per se. CRT is a big, loose academic movement that generally isn’t taught in K-12 schools (though that doesn’t mean “It isn’t taught in schools!” is close to an adequate political response, that it doesn’t pop up in teacher-training materials, or that some folks within the education system aren’t trying to increase its presence in K-12 settings). Some of the bills outlaw schools from forcing students to endorse certain sentiments often associated with CRT (which is already illegal — schools can’t generally force students to endorse beliefs they don’t want to endorse), some of them try to regulate whether and how schools can differentiate between students on the basis of race, some do genuinely ban classroom discussion of subjects no right-thinking person should want banned, and others, well… There are a lot of bills, many of them poorly written and conceptually confused. More on which in a bit.

But first: Shouldn’t media outlets, at bare minimum, honestly and accurately tell the public what is and isn’t in these proposed laws?

Let’s start with what happened late last year. Here’s the relevant paragraph from the Scientific American article, which was authored by the academics Daniel Kreiss, Alice Marwick, and Francesca Bolla Tripodi, and which is headlined “The Anti–Critical Race Theory Movement Will Profoundly Affect Public Education”:

The perceived success of anti-CRT campaigns also jeopardizes any meaningful discussions of systemic inequality as part of public school education. As of August, eight states had passed anti-CRT legislation, and another 20 had introduced or planned bills. These bills have the practical effect of preventing even tacit acknowledgement of racism or sexism. A bill passed by the Wisconsin Assembly, for instance, bans any books, educational materials, or classroom discussions that include terms like “racial prejudice,” “patriarchy,” “structural inequality,” “intersectionality” or, ironically, “critical self-reflection.” With this in place, it is hard to see how the Civil Rights movement, women’s suffrage or any number of events in American history could be discussed at all, let alone with depth. Indeed, such legislation may effectively “chill” the teaching of race by teachers scared to run afoul of conservative politics.

If you click on the words “bill passed,” you’ll see that the link points not to the bill itself, but to testimony about the bill given to the Wisconsin Legislature by its architect, Republican State Rep. Chuck Wichgers.

That testimony reads, in part:

I have an addendum to my testimony that lists several of the different terms associated with critical race theory or the words that are part of the praxis of the theory. Yes, it’s extensive and you can tell a lot of this was created in legal academia, but the point of this legislation is to prohibit it from being taught in our government schools.

…

[From the addendum itself:] Additional terms and concepts below that either wholly violate the above clauses, or which may if taught through the framework of any of the prohibited activities defined above, partially violate the above clauses in what is otherwise broadly defined as “critical race theory”:

Then follows a long list of words, including the ones mentioned by the Scientific American article.

One thing you’ll notice is that Wichgers himself hedges, saying that the items on the list either violate the law or may do so “if taught” through a particular ‘framework.’ He doesn’t specify which words land in which category, other than by pointing back to the text of the bill itself.

It’s quite easy to read that text, alongside the memo explaining what it does published by the nonpartisan Wisconsin Legislative Council. If you do so — a grand total of about seven pages of reading, mostly double-spaced — you’ll see that the actual text of the actual bill doesn’t really come close to banning any specific terms or concepts in the manner described by Scientific American and so many other outlets. It is not, in fact, “hard to see how the Civil Rights movement, women’s suffrage or any number of events in American history could be discussed at all” if the bill passed — not if you read it.

The meat is here:

118.018 Instruction and employee training regarding race and sex stereotyping. (1) A school board or the operator of a charter school established under s. 118.40 (2r) or (2x) shall not allow a teacher to teach race or sex stereotyping, including any of the following concepts, to pupils in any course or as part of any curriculum: [emphasis in the original]

(a) One race or sex is inherently superior to another race or sex.

(b) An individual, by virtue of the individual’s race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

(c) An individual should be discriminated against or receive adverse treatment because of the individual's race or sex.

(d) Individuals of one race or sex are not able to and should not attempt to treat others without respect to race or sex.

(e) An individual's moral character is necessarily determined by the individual's race or sex.

The rest of the bill lays out how this will be enforced (by cutting funding to offending schools), explains how complaints can be leveled, and calls for schools to put their curricula online so parents can see them. There’s also a provision banning public- and charter-school administrators from requiring teachers to attend trainings that include any of the above beliefs, and another that allows parents or guardians to “bring an action in circuit court” against schools they believe are violating the law.

Full disclosure — I don’t like this bill! Not at all. I don’t like deputizing parents and guardians to sue schools the moment they think they are violating this law. And, like a lot of supposedly anti-CRT bills, AB 411 casts too wide a net and risks banning, or at least having a chilling effect on, potentially useful discussions. What does it mean to “not allow a teacher to teach race or sex stereotyping”? The language is extremely vague and lends itself to some pretty bad outcomes.

Take, as an example, race-based affirmative action in college admissions. It is less popular than some people realize, but is undeniably a raging, live public-policy debate. Unless I am badly misreading this law, which seems to lack any sort of exception for situations where students are learning both sides of a debate, and which seems explicitly written to be as broad as possible (“in any course or as part of any curriculum,” emphasis mine), it would effectively ban any lesson even presenting the pro-affirmative-action side.

If you don’t think the bill would have that effect, explain to me how teaching about the affirmative action controversy wouldn’t run afoul of the clause about “An individual… be[ing] discriminated against or receiv[ing] adverse treatment because of the individual's race or sex.” Race-based affirmative action is, definitionally, a form of discrimination, albeit for what its proponents believe to be a socially virtuous purpose. Do we think state governments should be banning schools from even balanced classroom treatments of this issue? That seems ridiculous to me. And that tends to be the problem with these laws, which is an issue my podcast cohost and I have discussed previously.

But does the law ban specific terms like all these outlets say it does? It absolutely, 100%, clearly does not. Everyone writing about it for the aforementioned publications seems to have confused the text of the bill with Wichgers’ testimony and his very strange, much-too-broad list. I feel like he’s tipping his hand there — the subject of “racial discrimination” has been a mainstay of history and social studies textbooks for many decades, so why would he put it on this list? He wouldn’t be the first conservative to get super mad that schools are teaching kids something a bit more nuanced than “America is the greatest place on earth — a shining beacon of hope and democracy.” And this longstanding complaint is certainly one driving force behind all these proposed laws.

When I asked Wichgers about the list more generally in an email, he said, “It is my understanding that CRT is taught in praxis and through the pedagogy that may be associated with the words and phrases I included in my testimony.” So his basic view seems to be that these concepts, in some cases, are trojan horses for the icky CRT stuff he doesn’t like. But he was clear, in his email about what his bill does and doesn’t do: “Assembly Bill 411 does not ban any words or phrases, it prohibits concepts that enforce race or sex stereotyping; a violation of the Equal Protection Clause found in the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.” (I don’t understand the point of banning something that’s already banned, but again: Many of these bills are terribly written and are much more about culture-war point-scoring than resolving substantive issues.)

We should find it really worrying that these outlets proved incapable of accurately communicating the content of Wisconsin Assembly Bill 411. The Hill, Esquire, Slate, and Scientific American articles were produced by at least ten writers and editors (assuming one editor per piece — sometimes there are more). It doesn’t appear any of these ten individuals, whose jobs are to write and publish things that advance human understanding and present the world accurately, read the actual content of the bill they railed against, or even the nonpartisan memo explaining what it does in very digestible plain-text language, closely enough to truly understand what was in it.

What’s striking in reading these articles is that they provide readers with almost no accurate information about the actual content of the bill. You can read all four articles and come away with only a fantastical version of what the bill does, setting aside a few sentences in the Hill article dealing with some of the less important provisions (to be fair, the Slate and SciAm articles aren’t just about the bill, but about the broader anti-CRT movement as well). All four articles treat the bill as mostly a list of banned words, without making much effort to communicate its full content — content which is, again, a 30-second Google search away.

At the end of the day, none of this is really going to matter in Wisconsin. As the Hill reported at the time: “The proposal has virtually no chance of becoming law: It passed the Assembly on a party line vote, and even if it clears the Senate, it would almost certainly be vetoed by Gov. Tony Evers (D), himself a former superintendent of public instruction.” But the point is that a bunch of liberals, who in any other circumstance would come out loudly and proudly against “fake news,” spread exactly that — all because mainstream outlets that should be viewed as trustworthy couldn’t bother to enforce even very basic quality-control standards.

Cut To Present

Jeffrey Sachs is a politics instructor at Acadia University and a consultant at PEN America's Program on Free Expression and Education. He is a good-faith voice on these issues and follows them closely.

On Sunday, he tweeted:

Sachs is annoyed because the AP reported on Saturday that “Black lawmakers walked out in protest Friday and withheld their votes as the Mississippi Senate passed a bill that would ban schools from teaching critical race theory.” The other AP language he highlighted with dismay: “The bill says no school, community college or university could teach that any ‘sex, race, ethnicity, religion or national origin is inherently superior or inferior.’”

First of all, as the AP writeup itself notes, the bill (text here — it’s very short!) doesn’t mention critical race theory in its body — just in its title. Right off the bat, that makes it unlikely that it actually bans CRT. And the bill doesn’t exactly say it’s illegal to teach any “sex, race, ethnicity, religion or national origin is inherently superior or inferior” — rather, that language is one example of a list of beliefs schools are not allowed to force students to endorse. The relevant section starts thusly: “No public institution of higher learning, community/junior college, school district or public school, including public charter schools, shall direct or otherwise compel students to personally affirm, adopt or adhere to any of the following tenants [sic — they mean ‘tenets’].” (This is, again, already prohibited.) This bill, like the Wisconsin one, was widely misreported in major outlets — it wasn’t just the AP at fault.

Same deal in Florida (bill text here). Seemingly everyone has been screeching about how crazy it is that that bill bans private institutions from any training materials that could make white people feel ‘discomfort.’ But that’s just the same damn type of misreading. The bill bans “Subjecting any individual, as a condition of employment, membership, certification, licensing, credentialing, or passing an examination, to training, instruction, or any other required activity that espouses, promotes, advances, inculcates, or compels such individual to believe any of the following concepts constitutes discrimination based on race, color, sex, or national origin under this section[.]” Below that, one of the listed beliefs is that “An individual should feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin.”

So if the bill passes, it will outlaw the practice of compelling employees to undergo certain types of race trainings if they want to get or keep or advance within their job — including race trainings that force people to acknowledge that by being white, they possess some sort of original sin or whatever (this is a mainstay of Robin DiAngelo’s approach). Whatever you think about this, it goes without saying that this is very different from a bill rendering illegal any training that causes any ‘discomfort’ about race in a workplace setting.

(Update: Sachs thinks I’m misreading this. Here’s what he said after I sent him this post:

You're going to hate me, but you got one of the bills in your article wrong

The Florida bill. https://flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2022/148/BillText/Filed/HTML…

…

You're looking at the wrong section. Scroll down to lines 297-299. That bill says that "Accordingly, instruction on the topics enumerated in this section and supporting materials must be consistent with the following principles of individual freedom:"

"(f) An individual should not be made to feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.”

So in other words, the bill would (in one plausible reading) prohibit curricular material that makes an individual feel discomfort. That's my read, anyway. But it's a tricky bit of language.

I think he’s probably correct. “[S]hould not be made to feel” is such vague language that I probably should not have lumped it in with that other category of bill saying “You can’t force someone to believe XYZ.” This might be a your-mileage-may-vary situation, but overall I think I was wrong about this — in a newsletter about folks getting these bills wrong! — and I appreciate Sachs pointing this out.)

A Quick Note On “Legislative Intent”

Jumping back to to the Wisconsin bill for a minute, what bugged me the most was the response I got when I tagged the Scientific American authors on Twitter and suggested they correct their errors:

Marwick is a communications professor. She should care about spreading misinformation! But after I accused her of doing that, she simply reiterated what I’d already pointed out — that Wichgers’ testimony included a list of words. Of course she didn’t include the part where he explicitly used the word ‘may’ to describe the relationship he perceived between the terms he listed and the legislation he sponsored. Fischman, meanwhile, is an editor at Scientific American. He should care about his outlet spreading misinformation! But he simply argued that Wichgers’ list of banned words is “part of [the bill’s] legislative record,” as though that magically changes the text of the bill itself.

The concept of “legislative intent” is controversial, but the short version is that yes, in situations of genuine textual ambiguity, the courts can bring in other materials to try to figure out exactly what the architects of a given piece of legislation intended, including the legislative debate that preceded its passage. But the version of it being presented here, as an excuse for claiming a bill says stuff it plainly doesn’t, is fairly cartoonish. I guess “never say never” is the safest bet when it comes to predicting what some random judge somewhere will or won’t do, but still: In this case, the idea of a judge saying “Well, the bill doesn’t ban discussion of ‘structural racism’ anywhere, or contain language that would support such a ban, but the bill’s sponsor declared in separate testimony that perhaps that concept would qualify for the ban, so I hereby agree that structural racism can no longer be discussed in Wisconsin schools” seems pretty silly.

Again, it’s not impossible that Wichgers’ testimony could be brought to bear if there were genuine ambiguity about what the bill does and doesn’t do, but you can really just read the bill and see that it doesn’t ban the words on this list. And again, his testimony is itself ambiguous about which terms are banned, what with that language about how the items on the list either violate the bill or ‘may’ do so.

In any case, it really is plainly false for Scientific American to say the bill “bans any books, educational materials, or classroom discussions that include terms like ‘racial prejudice,’ ‘patriarchy,’ ‘structural inequality,’ ‘intersectionality’ or, ironically, ‘critical self-reflection.’” If you want to do the legwork of explaining how certain court rulings could possibly bridge the gap between the text of Wichgers’ bill and his list of magic words, go for it — but as a journalist or commentator, you can’t just say “Yup, these words are all now banned from Wisconsin schools.”

There’s a similar situation going on in Mississippi. The bill’s text mentions critical race theory, but nothing in it bans CRT itself. Technically, you could still teach critical race theory as long as you didn’t force kids to endorse certain viewpoints sometimes found in some CRT texts. You can’t just wave your hands and say “legislative intent!” and claim this bill is an outright ban on CRT because of its title. If you want to explore that possibility, do so journalistically — talk to legislative intent experts and cobble together a realistic account about how a bill that doesn’t appear to come close to banning CRT would ban CRT. But just read the damn thing and report on its actual words as a first step, is my point.

So How Should We Feel About These Bills?

Of course there’s the question of the bills themselves and how we should feel about them. One important thing to note is that their actual text isn’t the whole story. Part of the goal here is, in fact, to chill speech in classrooms. Just not quite as straightforwardly as the more lackluster coverage of this controversy is suggesting.

As Sachs put it in a PEN report published in November:

We need not ask ourselves how a rational person would interpret these bills. We need only ask how the most paranoid attorney or the most distracted and cash-strapped high school administrator is going to interpret these bills. They are going to immediately shut down any course content that would upset a sensitive student or an outraged parent.

This is itself a very interesting story! How are teachers and administrators going to respond? I’m not saying this type of reporting has been entirely absent, but there hasn’t been a lot of it, and there has been a huge amount of misreporting on the content of the bills themselves.

After I reached out to Sachs to get his thoughts on all of this, he sent a very helpful email that I want to include in full, and also pointed me to some very useful resources just published by PEN. First, his email:

Hi Jesse,

Prepare yourself. I'm going to give you way more information than you asked for, but I want to vent.

First of all, these bills are often terribly written. They are confusing, self-contradictory, and leave important terms undefined. Before we can even broach the topic of journalistic incompetence, we have to talk about legislative incompetence.

Worse still, many legislators are writing one thing on the page and saying something else in committee. Take Mississippi HB 2113, which was widely reported in the press as "banning CRT". Even a cursory glimpse at the legislative text reveals that's false. But note that the bill's summary states "that no course of instruction shall be taught that affirms" certain ideas associated with CRT. That's a totally false and misleading summary of what the bill would do, but it's not one made up by journalists. That's the legislature's fault. On top of that, during senate hearings on HB 2113, its chief sponsor affirmed that it was "absolutely" true that his bill would "ensure that everything that's being taught in our classrooms is colorblind, no preference over anything."

In other words, journalists are often seeing one thing on the page of a bill and being told another by the legislator who authored it. My point is not to excuse journalists who get it wrong, but rather to spread out the blame more widely.

But let's be real. Journalists, along with activists, pundits, and politicians, have very little incentive to describe these bills accurately. Supporters will tell you that they are harmless re-statements of established First Amendment jurisprudence. For instance, Chris Rufo wrote in the Wall Street Journal last year that the anti-CRT bills then under consideration in Tennessee and Texas "would simply prohibit teachers from compelling students to believe" certain ideas associated with critical race theory. False. Those bills forbade teachers from including those ideas in their pedagogy. They were not and are not about compulsion. They are about discussion. Either Rufo lied to the WSJ or he is incapable of understanding a legislative text.

For opponents of the bills, the same logic applies in reverse. Liberal content-mongers like Occupy Democrats know that they'll get far more clicks if they call HB 2113 a "ban" on CRT. Caution and precision do not sell. The collapse of basic due diligence at the Associated Press is less explicable but even more disheartening. I don't know if it is basic illiteracy or the belief that journalism works best when it makes people mad. Whatever the reason, it is getting worse.

At the core of it, nobody seems willing to actually read these things. I get it. It's tedious, frustrating work. So far, I've read and cataloged 122 different bills and let me tell you, it is no way to spend a pandemic. But the alternative appears to be letting falsehoods monopolize the public discourse.

What worries me the most is that we seem poised to make the same mistakes all over again. Right now, so-called "school transparency" bills are being rolled out all over the country. And who could possibly object to transparency? Nobody!...until you see what some of these bills actually say. Rufo is already out there acting like he's luring liberals into a trap, but (as usual) he has it precisely backwards. It's conservatives who are falling for the trick. They think they're just supporting some basic bill about parents' rights, when what they're actually doing is voting to let total strangers sit in a classroom and eyeball their kids all day. Centrists and conservatives are finally starting to accept that many of these anti-CRT bills are more dangerous than they initially believed. Watching them nevertheless make the same mistake all over again with "school transparency" is going to be too much to bear.

So that's my rant. I don't know if any of it will be useful to you, but it was certainly fun for me to get some things off my chest in slightly longer than tweet form. And thanks for calling me an honest broker. I'm trying to do that over at PEN, which I'm happy to say has been absolutely terrific on that score. They're very concerned with getting the analysis of these bills just right. I wish more organizations would follow that example.

Sachs also pointed out that, coincidentally, PEN just published another article of his on this subject, “Steep Rise In Gag Orders, Many Sloppily Drafted,” as well as a comprehensive spreadsheet tracking all the anti-CRT bills being debated. I haven’t fully caught up on all this yet, but knowing what I know about Sachs’ and PEN’s efforts on this front, I highly recommend all of this as further reading.

I’m obviously mad at mostly-liberal mainstream outlets that seem hellbent, on a day-to-day basis, on proving they don’t deserve our trust — you may have noticed this is a bit of a theme for me. But I don’t think that should be the only takehome message here. These bills are mostly bad and are, at best, a giant waste of time and energy and other resources. In many cases, the legislators drafting them barely even know what they’re mad about and are just trying to score political points among their riled-up constituents, many of whom have been hearing scare stories about CRT in their kids’ schools. Let’s not lose sight of all that.

A Final Note On Equivalencies

I’ve found that people react really angrily when I suggest the left is developing a fake-news ecosystem that is, in certain respects, starting to mirror the right’s. This is part of a broader go-to accusation, a cousin of whattaboutism, that some person isn’t spending the ‘right’ amount of time being upset about various problems. That is, why would I spend so much time and effort complaining about misreporting about the bills themselves given the dire threat posed by them? Isn’t the latter issue more important? Or: Why are you criticizing Robin DiAngelo, who whatever her faults is trying to fight racism, rather than focusing on fighting racism itself, which is still very much alive and well in the United States? Isn’t the latter issue more important?

I’m really, really sick of this argument — well, it’s more of a derailing tactic, to be precise — which comes across as a tic at this point. I guess on paper I don’t need to defend myself beyond “I can write about what I want to write about,” but it’s probably worth noting that this is exactly the sort of myopia that causes intellectual and political movements to corrode. Basically the question comes down to when we should criticize ‘us’ versus when we should criticize ‘them,’ and it’s implied that there is a proper ratio of us-criticism to them-criticism that must be adhered to in order to remain in the good graces of one’s fellow liberals or leftists.

But I don’t have any obligation, whatsoever, as a writer, to follow any such made-up rules. There’s also a lot of question-begging going on here. For example, it would be useful to know how worried we should be about these supposedly anti-CRT bills. You can’t really establish that without knowing exactly what’s in them, and you can’t know what’s in them unless someone tells you or you read them. So if a bunch of media outlets are refusing to do their jobs and are spreading misinformation about the bills, it’s unclear how we can even get to a place of having a reasoned conversation about how much of a threat they pose, which would be a prerequisite to figuring out the right ‘ratio’ in the first place, if you’re into ‘ratio’ thinking (which I’m definitely not).

What I’m saying is this all makes us stupider.

Now, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that I do, as a matter of fact, think the misinformation situation on the right continues to be much worse than its counterpart on the left, for various reasons. That partly explains why tens of millions of Americans continue to think Donald Trump won the last election. Whenever I express this view, other people get mad at me because they think I’m just trying to throw up the I’m A Good Liberal signal. But I don’t know what to tell you, because I actually think right-wing misinformation is very, very bad! I just got tired of writing about it and think there is basically blanket coverage of that subject, anyway. I’ll likely revisit it at some point but no one can credibly claim it is being ignored in the meantime.

Either way, this is all sort of beside the point. The point is, or should be: It is worrisome that mainstream liberal and liberal-leaning media outlets start to stumble down a very truth-y road. And the present controversy is a striking example, because no one is being asked to clear a particularly high hurdle. It isn’t hard to read a bill and to accurately relate what’s in it. It isn’t hard to differentiate between the text of a bill and testimony given about that bill. It isn’t hard to get in touch with a state rep to see if he can clarify things — I heard back almost immediately from Wichgers, and many of these state legislators are quite thirsty for the attention of journalists. Why did so many outlets fail to do this basic homework, instead misinforming everyone about such a basic, easily checked set of facts? This seems like an important issue to me, and I find the notion that I should ignore it just because people are mad about a perceived violation of a completely made-up ratio-rule to be pretty silly and annoying.

Questions? Comments? Complaints that I’m much too focused on A, B, Q, and Y, when C, D, F, G, L, and Z are obviously much higher priorities? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

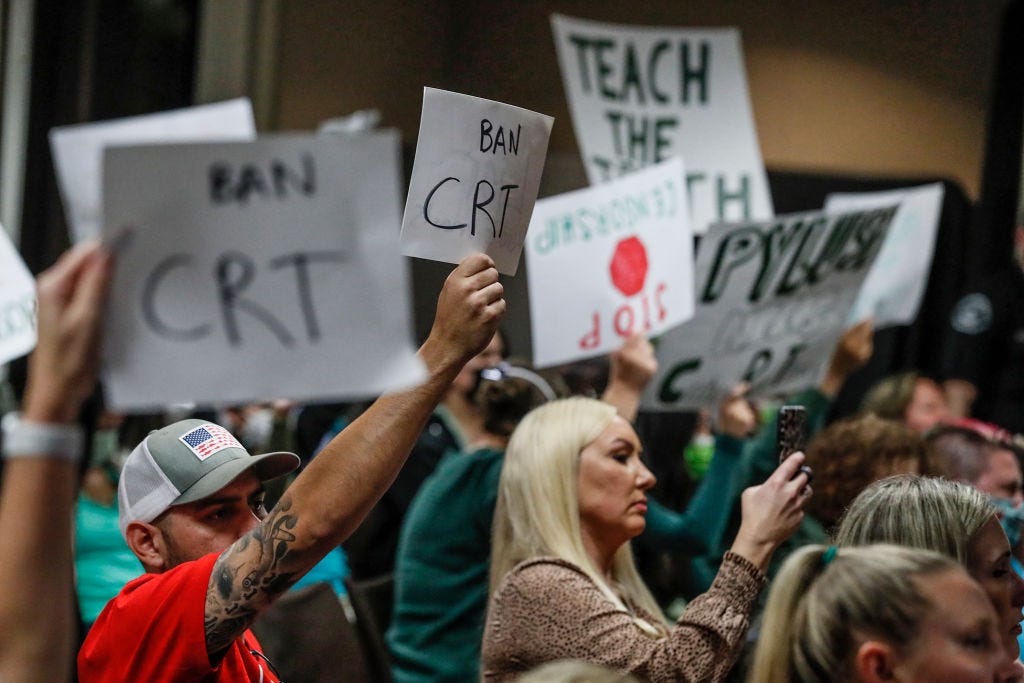

Image: Yorba Linda, CA, Tuesday, November 16, 2021 - An even mix of proponents and opponents to teaching Critical Race Theory are in attendance as the Placentia Yorba Linda School Board discusses a proposed resolution to ban it from being taught in schools. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)