Is It Offensive To Use The Term "Totem Pole" Informally?

And what about 'kosher'? Is that, you know, okay?

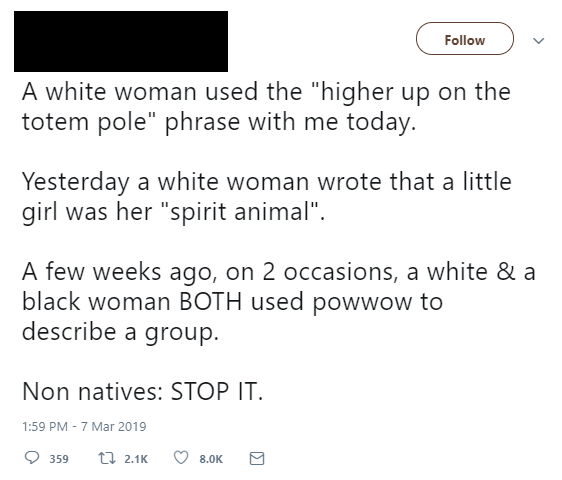

Someone sent me this tweet and it got me thinking:

There’s definitely some support for this sentiment — both the two-thousand-plus retweets, for what that’s worth, and, more anecdotally and broadly, the fact that there does appear to be a movement on the left to enact more conservative norms with regard to which sorts of people are allowed to use which sorts of words.

I’d like to make a good-faith effort to explain why I don’t think it’s offensive for a non-Native person to use a term like “totem pole” or “spirit animal.” I’m going to discuss this in a really informal way, relying on what strike me as common-sense understandings of how English works, of what’s ‘happening’ when someone uses a term or idea from a culture that is not their own to express something in English. I’m sure some sophisticated stuff has been written on this, so please send me your recommendations if you have any. But I don’t think there’s anything wrong with talking about this stuff at a pretty basic level. We need to be able to debate what is and isn’t offensive without hauling out giant philosophy-of-language tomes, after all.

Okay, so: Imagine Ted, a gentile, says to his wife, Christina, also a gentile, “I asked the boss if it would be kosher for me to leave early on Friday so we can hit the road to beat the beach traffic, and he said it was fine.” That utterance is meaningful to both of them because they are, at the very least, familiar with the less formal, precise definition of kosher that has caught on (they may or may not be familiar with what the term originally meant before it caught on in this manner). That is, here kosher (obviously) doesn’t mean Ted asked his boss if leaving early would break traditional Jewish dietary law, but rather that he asked his boss if leaving early would be okay.

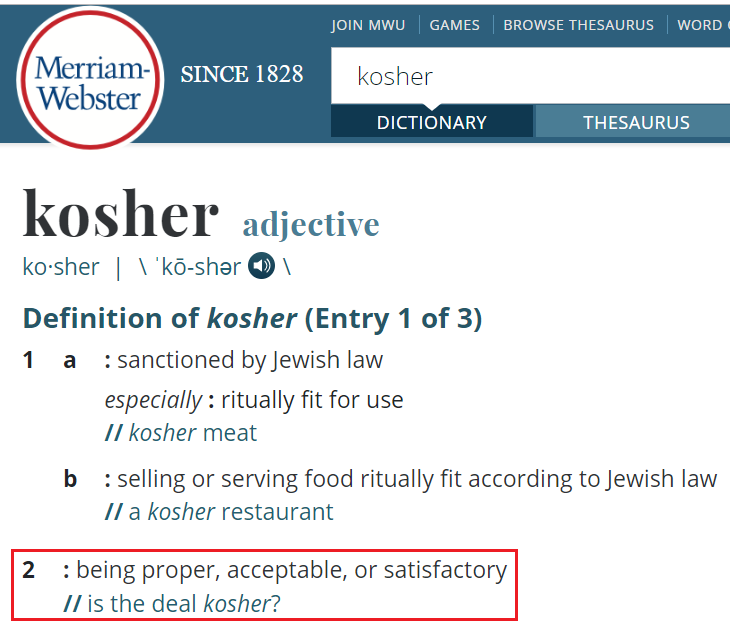

This secondary definition is right there in Merriam’s:

I would argue that the reason kosher is used in this way is that Americans have developed a certain degree of familiarity with Jewish people and customs — it’s a sign of a certain form of assimilation. How else would it catch on? Today, in 2019, we’re probably at a point where the secondary definition has been in use long enough (since 1896, in fact, according to this source) that not everyone even knows kosher had an original definition; maybe some people just think it’s a funny-sounding word meaning “being proper, acceptable, or satisfactory,” and they don’t think about it much beyond that because who has time for etymology? But along the way, there had to be a period during which the term’s definition expanded outward based on knowledge of what it originally meant, right?

It feels like that familiarity is a necessary bridge from the old definition to the new one. Once the new definition is established and repeated enough, you don’t need the bridge anymore — to torture this metaphor, for some people the bridge has effectively been blown up, and they are trapped on the ‘new’ side of the, uh, usage river(?), familiar with the term’s new but not old definition.

Kosher has been around for awhile, but you can see this happening now with some other words from other cultures. If I say to a friend, “I’m trying to stay away from Carl — I genuinely don’t know what I did, but lately it feels like he’s embarked on some sort of jihad against me,” that usage relies on my friend understanding the connection between (one definition of) jihad and violent conflict, and further understanding that I’m taking one slice of the term’s original definition — a slice involving intense conflict — to use it more informally. This is a more colorful and memorable way of saying Carl is pissed at me than saying, well, “Carl is pissed at me.” Maybe this new usage will catch on and in 50 years, even people with no knowledge of the original Arabic word will use it more informally.

In both these cases, kosher and jihad, it strikes me as obvious that the speaker is not directing any dislike toward Jews or Muslims. They are simply using words that started out having one or more original definitions, and, as words are wont to do sometimes, took on other, looser definitions, too. This is how language works. If you really, really wanted to dig for offence, you could come up with a reason to be offended — “Jewish dietary laws are an important part of an oppressed people’s millenia-long history, and you’re trivializing that history by using the word kosher to refer to your dumb beach trip” — but would you want to sit next to the sort of person who would say something like that on a plane? (I recognize that these words might be used by bigoted people, but that’s a different question from whether this type of definition-loosening is intrinsically harmful or bigoted. And using jihad in an informal sense no more suggests most Muslims are jihadists than using kosher in an informal sense suggests most Jewish people are religiously observant.)

So, back to totem pole and pow-wow and spirit animal. These terms have developed secondary, less formal definitions because American English-speakers are generally familiar with their original definitions. Most Americans know what totem poles and pow-wows are. I bet fewer could give a solid, accurate definition of ‘spirit animal,’ but that most people understand that it means, more or less, a being I feel a connection to, or which reflects my personality. So “He’s higher up the totem pole than she is” is a more colorful way of saying “He is held in higher esteem than she is.” “That pow-wow about the kitchen situation was pretty tense” is a more colorful way of saying “That house meeting about the kitchen situation was pretty tense.” I don’t think these terms are directing any hate or bigotry or dislike at Native Americans, because they’re being used in exactly the same way kosher or jihad are in the above examples — this is just how language works.

In the spirit of the above hypothetical person you wouldn’t want to be stuck on a flight with, I suppose you could make some sort of argument about how it’s okay to borrow some terms and concepts, but not ones from oppressed groups (unless you’re a member). Setting aside the difficulty of dividing the world neatly into “oppressed” and “not oppressed,” boy does that make me feel uncomfortable. That would mean that it would be kosher (sorry) for me to use Sturm und Drang and cul-de-sac, which come from German and French, respectively, because neither German nor French people are historically oppressed — there are all sorts of cheap jokes of the form “Except when it comes to…” I could insert here, but I’m going to resist the temptation — but not okay for me to occasionally sprinkle my speech with references originating from Native or Muslim culture (I guess since I’m Jewish I could still use Hebrew- and Yiddish-originating words and references, which is good, because oy vey would I schvitz if anyone told me I couldn’t ). It would mean I couldn’t sometimes say Yo to a friend when saying hello or Peace when saying goodbye — two expressions I’ve picked up from simply growing up and moving around over the years in a very diverse country — because those, too, originated from a power-down group: African-Americans.

Doesn’t this idea make you a little sad? The idea of only historically powerful groups getting to have their ideas and words borrowed by and integrated into English? Wouldn’t we be missing out on something?

As a final note, I should recognize I sometimes get into trouble trying to logic my way into or out of situations that aren’t really about logic. A lot of the time, when someone makes a claim about language that doesn’t really make sense, logically and causally — my favorite recent example is definitely the claim that using language like ‘colonize’ to refer to space exploration “erases the stories of and violence against the people of color who lived and ranched in the [American West]” (erases!) — there’s a kernel of real truth and hurt underlying it. In this case, yes, European colonization murdered millions of people and plundered untold wealth. And when you have something this big and awful — or, relatedly, something as big and awful as the genocide and continuing oppression of Native Americans — a little bit of that bigness and awfulness is going to spill out into forms of outrage or censure or petty-seeming attempts at control that might not entirely make sense. That’s human nature. People have lashed out over far less.

But at the end of the day, I just think the best way to puzzle this stuff out is to discuss it openly, not to treat claims of language-causing-harm as sacrosanct and therefore beyond dispute. A small, possibly hopelessly naïve part of me thinks that if people thought through how language works a bit more clearly, they’d see less reason to fear the parts of it I find so wonderful and peppery and exciting.

Questions? Comments? Fatwas? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com, or on Twitter at @jessesingal. Lead image via.