If You Want To Help Vulnerable People, You Need To Turn Them Into Faceless Abstract Units (Unlocked)

"This is just an abstraction to you." I mean, yes! It has to be at some point!

My subscribers voted, overwhelmingly, that they are okay with me sometimes unlocking previously paywalled posts that are at least three months old. That’s what I’m doing here — this post ran on 3/26/2021, and the original version lives here. As always, I’m cloning it to protect the privacy of subscribers who commented on the original — this version was created on 6/28/2021.

If you find this article useful or interesting, please, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. My paid subscribers are the reason I was able to write this piece in the first place, and they’re the ones who keep this newsletter going.

The chapter of my book I'm most excited to get out into the world is probably the one about Comprehensive Soldier Fitness. CSF is an Army program that was adopted in the late aughts, at the height of a horrifying PTSD crisis. Soldiers were enduring incredibly grueling tours in Afghanistan or Iraq or both, coming home with crippling trauma, and suffering immensely. An alarming number of them were killing themselves or — less frequent but more attention-getting — others. (Update: This chapter was adapted into an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education.)

So the Army adopted CSF as a universal, mandatory program geared at preventing PTSD and suicide. The why is complicated — BUY MY BOOK! BUY MY BOOK! — but the Key Takehome Points, more than a decade and something like half a billion dollars later, are surprisingly easy to summarize:

1. CSF doesn't appear to do anything to prevent PTSD or suicide.

2. There was little sound theoretical reason to think CSF would do anything to prevent PTSD or suicide.

Okay, good post! See you guys next week.

Just kidding. I want to talk a little bit about why the final version of the chapter, while quoting a lot of people, including veterans and people on both sides of the CSF controversy, actually doesn’t include the voices of soldiers themselves discussing the CSF experience. Because I think this ties into some broader debates going on about the value of testimony and the supposed perils of ‘abstraction.’

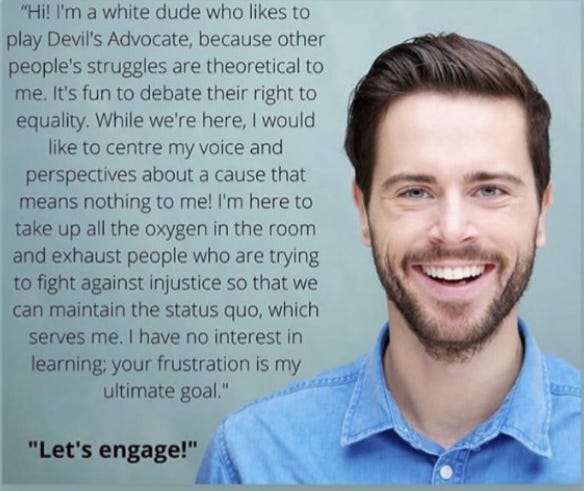

In the past, I've criticized the idea communicated in this meme, which I once saw tweeted approvingly by a New York Times opinion editor:

It’s a smug-looking white guy — could be a friend or family member of mine, really — with the text:

Hi! I’m a white dude who likes to play Devil’s Advocate, because other people’s struggles are theoretical to me. It’s fun to debate their right to equality. While we’re here, I would like to centre my voice and perspectives about a cause that means nothing to me! I’m here to take up all the oxygen in the room and exhaust people who are trying to fight against injustice so that we can maintain the status quo, which serves me. I have no interest in learning; your frustration is my ultimate goal.

Let’s engage!

The beliefs expressed (sarcastically) in this meme are pretty widely held in my corner of the world. You will often see people making arguments like “This is all just abstract to you.” The clear implication is that having a direct stake in a given issue gives you an advantage in understanding and solving it, and that therefore your views should be deferred to.

When I first encountered this meme, I did a little tweetstorm about it, tying Smug White Guy into my long article critiquing the implicit association test, which is one of the works of journalism I’m proudest of, and which was adapted into a (significantly different) chapter in my book as well:

Seeing someone whose job is to edit New York Times op-eds tweet this approvingly really got me thinking. And yes, I am probably shooting myself in the foot by tweeting this, because of COURSE I would like to write for the page again. So be it. Three and a half years ago, I wrote a very long piece on the implicit association test. The piece was driven in part by my belief that the IAT was distracting from a more realistic, evidence-based understanding of racism in America -- one focused more on structures. I believe this piece played a small part in nudging the conversation. These days, I am seeing a lot of people publicly decrying institutions’ over-reliance on this test, especially since there’s no evidence to suggest it does anything. This is good. The test was overrated and the science overhyped. Of course, *at the time I wrote about it* it was still very widely accepted, and mentioning it was (and sorta still is) a way of demonstrating one’s anti-racism bona fides.

I could see someone like [this editor] responding to a piece like my IAT critique with, well, that meme: Why am I wandering into this conversation when I *personally* have nothing at stake? Why am I debating people's “right to equality” by gainsaying the oh-so-vital IAT? Why am I turning a matter of people’s very lives into an abstraction, into statistics and correlations? Of course, the answer to all these questions is that in order to improve the world, we need to understand it better, bringing to bear the sharpest, best tools available. And I don’t want to work in a journalistic landscape where someone trying to do that will be instantly derided as some sort of “Just asking questions” dudebro simply for having the wrong skin color or questioning a currently faddish concept (that might be destined to die out soon anyway!). Anyway, that's all I’ll say. It's one thing for random people to tweet stuff like that, but seeing industry gatekeepers do it is another story....

In short, while I’m of course against anyone questioning someone else’s “right to equality” or barging into a conversation space and taking up all the oxygen, I don’t really think that’s what this is about. Rather, it’s part of a broader attempt to derail certain criticisms by positioning the interlocutor in question as some sort of callous hobbyist who is just asking questions because he likes to debate, is skeptical of this whole ‘equality’ thing, or is otherwise a dick.

Back to the Army: The reason the chapter doesn’t include a bunch of soldiers saying “I did CSF, and here’s why I think it was [good/bad/whatever],” is that this actually doesn’t matter. Anecdotal accounts don’t offer us all that much information about whether the program worked. That’s a matter of statistical proof, and when it comes to statistical proof anecdotes are useless and sometimes worse (though hold tight for some imminent slight backpedaling).

Now, where I do quote veterans is on the subject of what it’s like to have PTSD. “What is it like to have PTSD?” isn’t a statistical question in the way “Does Comprehensive Soldier Fitness accomplish its stated goals?” is. You can’t show, statistically, what it’s like to have PTSD any more than you can show, statistically, what it is like to be a bat. If, as someone who doesn’t have PTSD, you’d like to know what it’s like to have PTSD, the best thing you can do is Listen To People Who Have PTSD. If you’re trying to treat PTSD? Sure, you should Listen To People Who Have PTSD in the sense of making sure the treatments are comfortable for them to go through, but overall, that honestly won’t tell you that much about how well you’re doing, because people aren’t good at introspecting accurately with regard to their mental health and predicting what will improve it. If they were, Americans wouldn’t spend something like $10 billion per year on self-help.

I think there’s a chronic mixing-up of these two types of information. “What does it feel like to be followed around a convenience store because of your race?” is a mostly qualitative question. “How can we reduce racism among convenience-store owners” is a mostly quantitative question. I can read an account of experiencing this racism and hopefully gain some empathy and understanding of what it feels like, but I would never then email the author to ask them for their thoughts on building an anti-bigotry intervention. Think about how weird it is to even think that I should! “I had the flu, so I can create a treatment for the flu” is a very weird sentiment. For some reason people think folk-psychological theories are more useful than folk-medical theories, but often they aren’t.

Much of this goes back to left-wing identitarianism, which is a very strange, mystical, feelings-driven ideology, if you can even call it that. So you can’t really expect its adherents to explain their views in the normal, coherent sense. But boy do they express them with confidence! You will see otherwise genuinely brilliant people loudly proclaim that the only way to fight racism/homelessness/poverty is by “listening to” people who are victimized by it, and that people who treat these ills as “abstract debates” or whatever are committing some sort of sin.

But if you want to end homelessness (to switch gears) of course you need to have an abstract conversation about homelessness-ending efforts! There’s a debate over how to best help homeless people! Given perpetually limited resources, is it better to give homeless people direct cash payments? To just plop them in available apartments? To link them up with resources to fight addiction? How should the pie be divvied up? What is the alternative to developing some way to weigh the pros and cons of these approaches that will, in the end, be ‘abstract’? Should we just hold a bunch of meetings and let the side whose advocates can scream the loudest win the day?

I was joking when I typed that last part but I think that’s sort of what some left-wing identitarians want. “I screamed very loudly that this didn’t make me happy so it shouldn’t be allowed to happen.” This might seem uncharitable, but you can search high and low for any attempt on their part to explain what they mean by “listen to X people” — they certainly don’t listen to X people who disagree with them — or what they see as the alternative to the mainstream social-scientific approach to this sort of problem-solving, and you will find zilch. Nada. They are making what is, in fact, a radical claim but they’re not doing any of the legwork of defending it. Because it’s really just a derailing tactic.

Okay But On The Other Hand (Slight Backpedaling)

Perhaps for the sake of making my argument forcefully, I’m positing too clean a divide. There’s one sense in which “listening to” homeless people or the victims of racism or domestic-violence victims or anyone else is obviously important not just from a gaining-empathy standpoint, but also from a program-design standpoint. If you swoop into a new homelessness-fighting effort not knowing anything about the day-to-day lives of homeless people, and as a result you open up a gleaming new transitional housing center five miles outside the city center, far from any mass transit, and there’s no way for most of the people who might benefit from it to get there, then sure: You should have Listened To Homeless People. During the Freedom Summer and other instances of educated white northerners attempting to help liberate the South during the civil rights movement, this was a famously common problem: over-educated college kids barging into communities and wanting to help, but doing so in an aggressively self-assured manner and talking over local activists who knew what they were doing.

Or to use the more concrete example of Comprehensive Soldier Fitness: An anthropologist named Emily Sogn has researched CSF, in part by interviewing those who have participated in it. She found that soldiers reacted particularly poorly to the Global Assessment Tool, the mandatory survey instrument that serves as the backbone of CSF and which was supposed to help the Army gather useful information on soldiers’ well-being (though, as I write in my chapter, it wasn’t designed well enough to actually serve this purpose).

We unfortunately had to cut this material (in the course of writing a book you inevitably have to get rid of a lot of worthwhile stuff), but here’s some language from one of my book drafts:

Yes, it is true that the Army has produced various PR materials in which soldiers claim that CSF has been great or even life-changing, but in an Army of 1.1 million people any program is going to be liked by some of them. What seems to be more common is that soldiers view CSF as a chore or a PR gimmick they need to grind their way through rather than something to actively engage with.

That was the conclusion of Emily Sogn, a New School anthropologist whose doctoral dissertation was on CSF, at least. Most of the issues stemmed from how soldiers viewed the GAT, she told me. “Soldiers are often very flip, very casual, sometimes very hostile about the effectiveness of these surveys,” she said. “They’re often very strategic about how they take these surveys.” This feeling extended up the command chain. “Mostly what I heard in terms of the kind of command climate was that there was a casualness, that the soldiers sensed that it wasn’t very important and that they could do it fairly quickly — and that what they were doing was just getting it done, not that it was something they were supposed to kind of reflect on and treat in a sincere way, comes from the commanders’ attitudes toward it,” Sogn explained. “That this was one task among many, many tasks, many of which the commander deemed more important.”

This is a nice example of how “listen to soldiers” can be useful when designing something like CSF. Adopting their insights might lead a CSF architect to realize that if your survey is the 100th piece of paperwork a soldier has to fill out in a year, and if soldiers already feel like they are overwhelmed by these tasks, it is unlikely they will take it seriously. Had CSF benefited from a longer, more thoughtful design process (it didn’t), perhaps qualitative interviews with soldiers would have uncovered this jadedness about surveys and led to the decision to either make the GAT shorter, change the way it is presented to soldiers, or otherwise take some action to prevent it from being seen as just another bit of annoying paperwork atop an already imposing pile.

So I don’t want to completely throw out Listen To X as a sentiment. Listening is great! But of course at some point, if you want to actually help the soldiers you are Listening To, you have no choice but to abstract them. You need to turn the fully fleshed-out, textured human that is Lieutenant Dan into an abstract unit in your n = 10,318 sample so that you can actually do science and hopefully come up with an intervention that will help him come to peace with losing his legs.

Questions? Comments? Attempts to abstract me? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The image is Kandinsky’s Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor).