How An Academic Article On Violence And Religion Almost Got Unpublished For Political Reasons

An interesting case study in politics and science colliding in an unhealthy way

Quick note: I originally pitched and had this story accepted as a fairly short, bloggy, “Check out this controversy in academia”-type item for New York Magazine’s website. But as I dug into the details, I realized I wanted to go a bit longer and more in-depth than would work for a NYMag.com piece, so I decided it might be a better fit for Singal-Minded, given that I likely have a disproportionate number of readers interested in this sort of story. This is the first time I’ve written up something for Singal-Minded that started as a potential article for another outlet, so I figured I’d note that — this will also explain a reference to NY Mag you’ll see toward the end.

Oh, and if you want to support this sort of thing...

It’s neither original nor radical to point out that all science is, to a certain extent, political. Science is a human endeavor and all human endeavors entail politics in one sense or another. So the questions of which academic researchers enjoy widespread publication and which ones watch helplessly as their careers languish, and of which areas of research get a great deal of attention and which are neglected, are tied up in politics — always. Usually, the forces that politicize science remain somewhat in the background. Quiet decisions are made for questionable reasons, and the process is obscured to the public.

That’s what makes the case of a contested upcoming article in Contemporary Voices: St. Andrews Journal of International Relations, or CVIR, is so interesting: According to Joshua Wright, a postdoctoral fellow at Simon Fraser University and one of the article’s two coauthors, two editors at the journal attempted to have him and his coauthor modify its contents for political reasons after it had already been accepted for publication following a round of edits. Correspondence and a tracked-changes document Wright shared with me support his account.

CVIR has since relented and agreed to publish the article without all of the changes it originally requested, but this messy, somewhat convoluted episode is still fascinating for two reasons: First, it pulls back the curtain on an unusually straightforward-seeming episode of political concerns interfering with the scientific publication process. And second, it demonstrates how social media and the growing norms toward transparency in some areas of scientific research are making it easier for academics convinced they are being treated unfairly by the system’s gatekeepers to respond publicly.

In April of 2018, Wright and Yuelee Khoo, then an undergraduate research assistant of Wright’s (he is entering a PhD program in biostatistics next fall), submitted a paper with the title “Empirical Perspectives on Religion and Violence,” a preprint of which can be read here, to CVIR. The point of the paper was simple: to take a broad, critical overview of the evidence for and against the “religion as cause” argument, which “implies that religious faiths are more inherently prone to violence than ideologies that are secular.” In the paper, Wright and Khoo argue that there is less support for this view than one might think. “Following an evaluation of the scientific literature on religion and violence, we argue that wherever evidence links specific aspects of religion with aggression and violence, these aspects are not unique to religion,” they write in the abstract. “Rather, these aspects are religious variants of more general psychological processes. Further, there are numerous aspects of religion that buffer against aggression and violence among its adherents.”

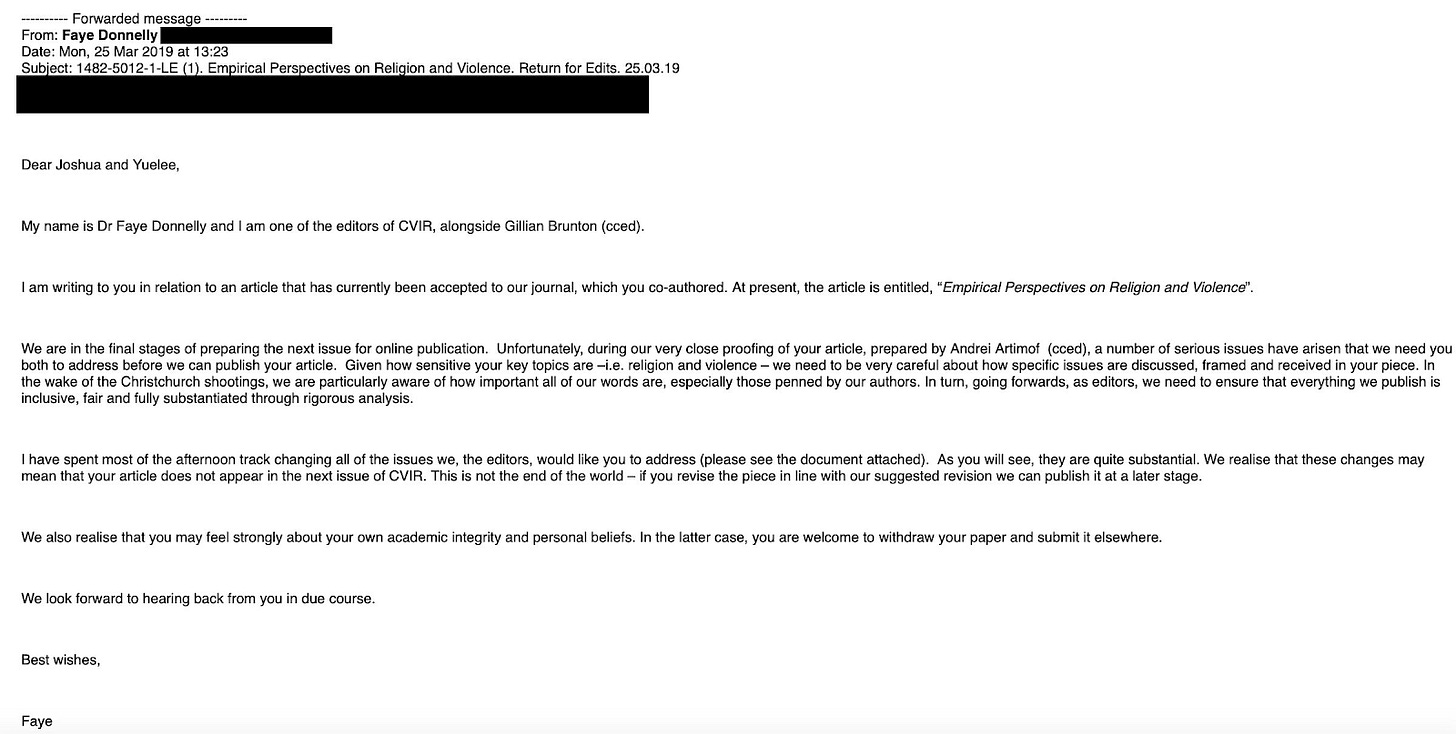

In December of last year, after the coauthors made a round of standard requested edits for CVIR, the journal notified them it had accepted their paper for publication. Then, in late March, the coauthors received what Wright viewed as an unusual email from Faye Donnelly and Gillian Brunton, the two editors of CVIR (there was some sort of email-address snafu, according to Wright, and so they didn’t actually receive the email until the latter part of April). “We are in the final stages of preparing the next issue for online publication,” the email read in part. “Unfortunately, during our very close proofing of your article, prepared by Andrei Artimof (cced), a number of serious issues have arisen that we need you both to address before we can publish your article. Given how sensitive your key topics are -i.e. religion and violence - we need to be very careful about how specific issues are addressed, framed and received in your piece. In the wake of the Christchurch shootings, we are particularly aware of how important all our words are, especially those penned by our authors. In turn, going forwards [sic], as editors, we need to ensure that everything we publish is inclusive, fair and fully substantiated through rigorous analysis.”

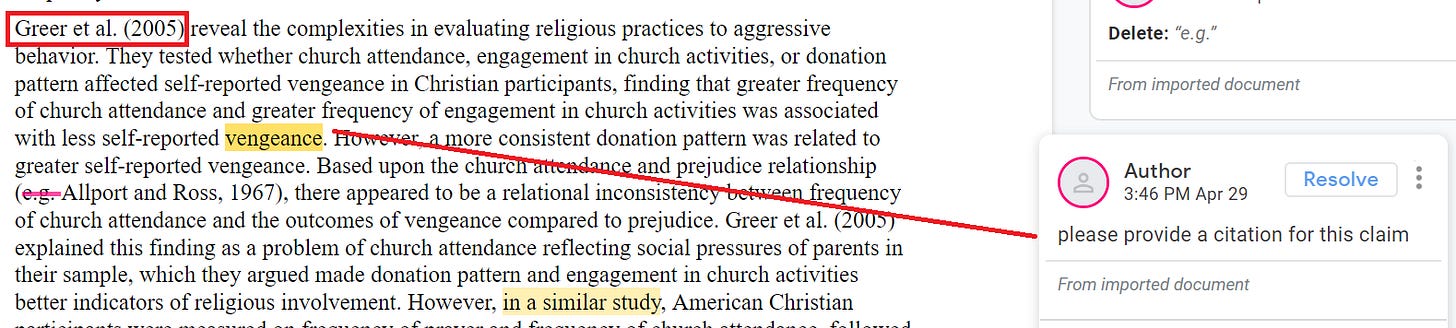

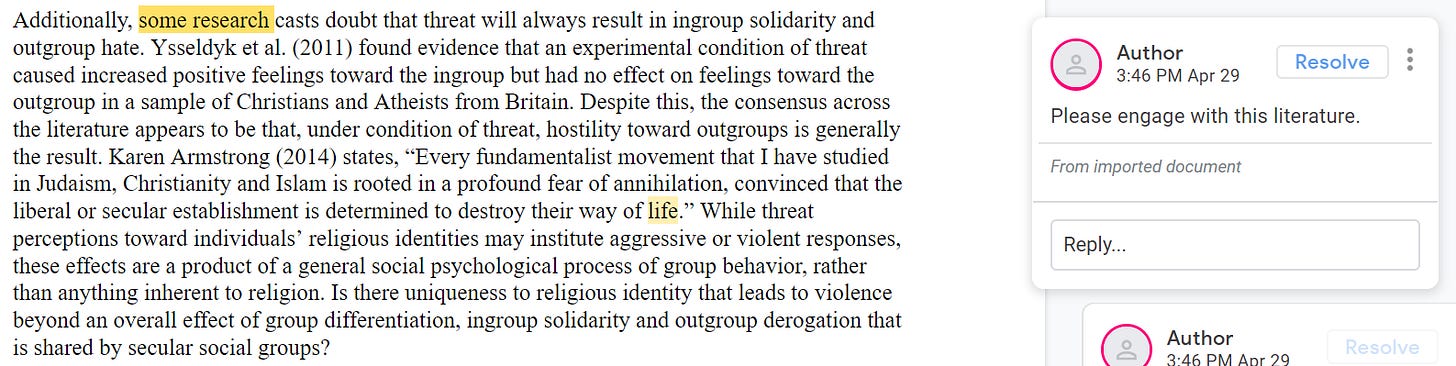

The editors asked the coauthors to make some “quite substantial” changes that, they said, might delay the article’s publication to a later issue of the journal. Wright was not happy with the request, which led to some further back-and-forth. But the key piece of evidence here is the tracked-changes document Donnelly and Brunston sent to Wright and Khoo, and which Wright shared with me. On the whole, it is strange.

For one thing, it contains multiple instances in which Wright and Khoo are asked to source claims that they sourced right there, in the text being referenced, or to engage with literature they clearly are engaging with. Here’s an example of the former:

There’s a citation one sentence prior to the highlighted word.

And here’s an example of the latter:

The paragraph is devoted to “engag[ing] with the literature” in question.

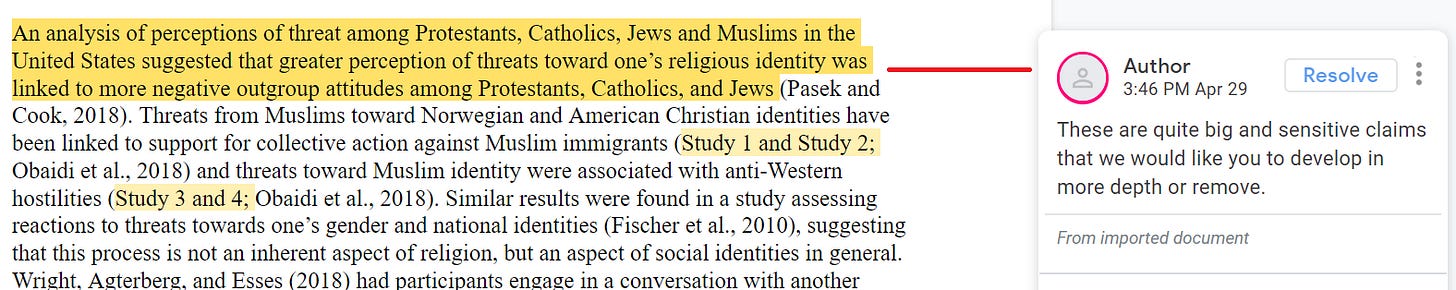

Elsewhere, Wright and Khoo are asked to provide further support for, or remove, rather basic claims that appear to be supported in the literature they are citing:

In this case, Wright and Khoo are reporting a simple, straightforward correlation revealed in a research study — a correlation that wouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone with a bit of exposure to social psychology. It’s unclear why it constitutes a “big and sensitive” claim that requires further documentation.

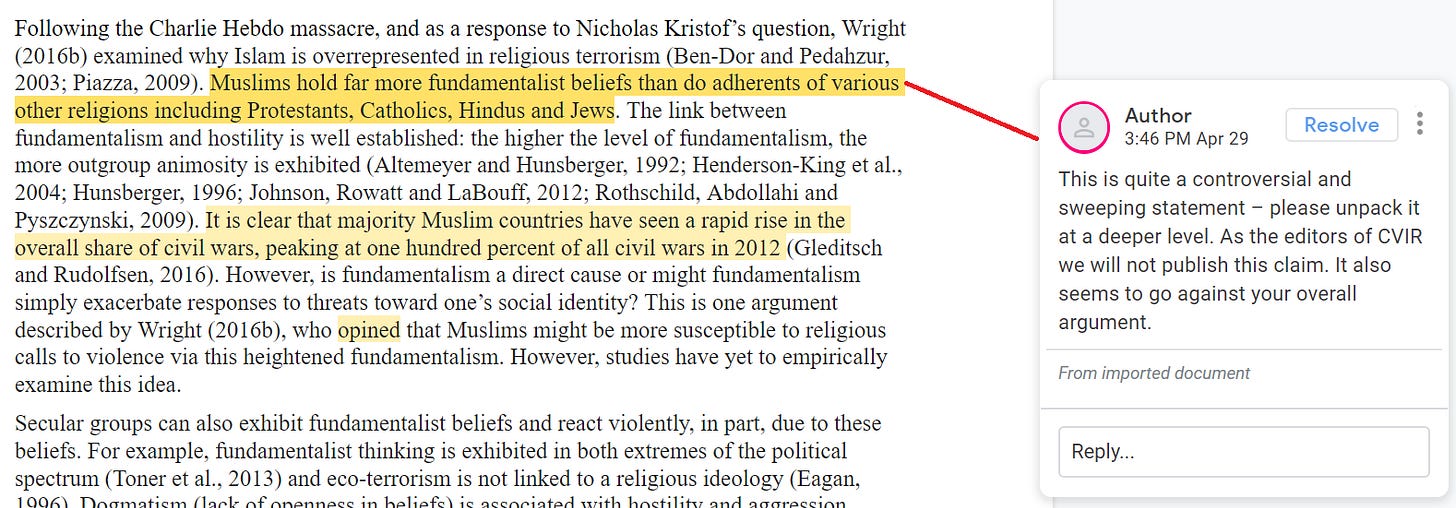

Another example:

Here, Wright and Khoo reference a paper Wright published in 2016 in which he successfully replicated an older finding showing that in the United States, at least, Muslims score significantly higher on a fundamentalism scale than do members of other religious groups. It appears to be a sturdy finding, so it’s strange to see the editors say they “will not publish this claim.” In arguing that it “seems to go against your overall argument,” the editors also exhibit a clear misunderstanding of the point of a paper like this, which is to evaluate all the evidence for a claim, for and against, and come to a best-guess general conclusion.

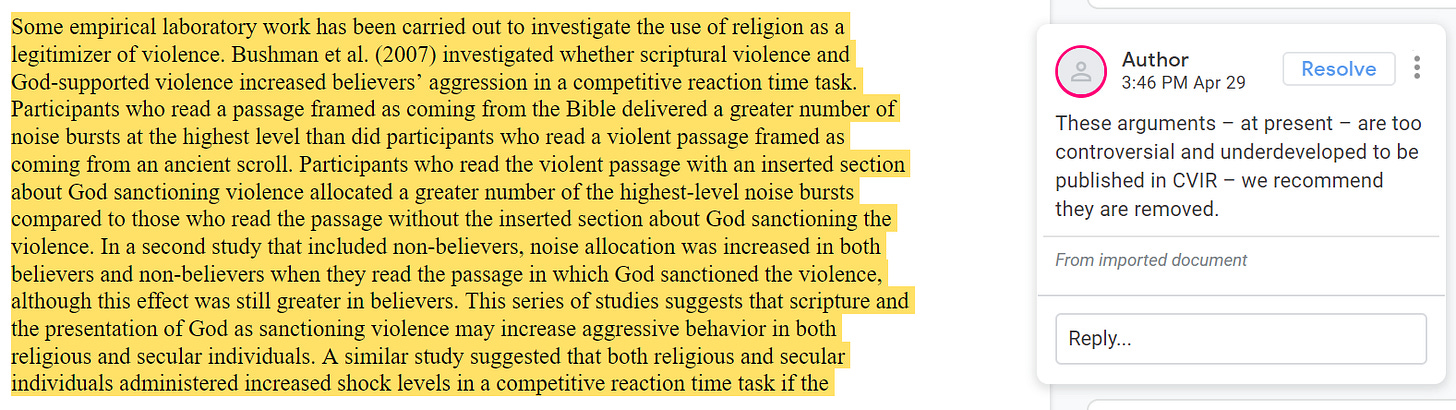

This might be the most striking example of the editors refusing to publish one of Wright and Khoo’s claims, though:

If, in the Year of Our Lord(s) 2019, a journal with the term International Relations in its name finds the claim that scriptural support for violence might make religious adherents more violent too controversial to publish, it’s unclear what the point of this sort of scientific inquiry is at all.

***

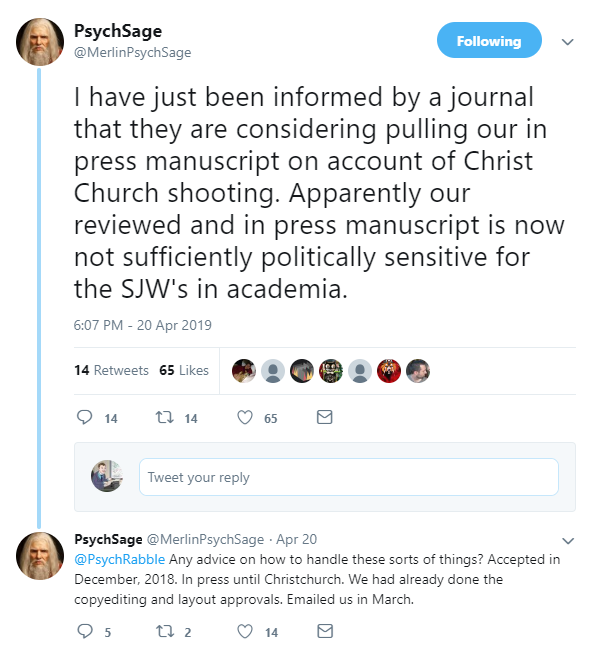

Wright was rather outspoken in his criticism of the initial email he received from CVIR. On April 20th, he tweeted, “I have just been informed by a journal that they are considering pulling our in press manuscript on account of Christ Church [sic] shooting. Apparently our reviewed and in press manuscript is now not sufficiently politically sensitive for the SJW’s [social justice warriors] in academia.”

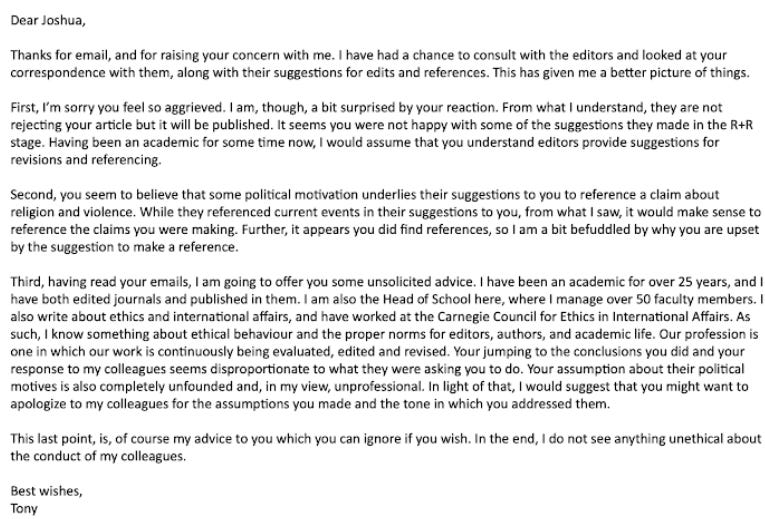

Wright also sent an email to Anthony Lang, the chair of the political theory department at the University of St. Andrews, with “unethical editors” in the subject line. Lang sent him back this email, as passed on to me by a press officer at St. Andrews:

There’s a lot going on here. The email does seem to focus more on Wright’s tone and immediate reaction to the CVIR request than on the fact that the request itself was unusual — Lang is writing as though Wright simply overreacted to a normal request for revisions (“R+R” is a reference to “revise and resubmit,” a standard response to a paper a journal is interested in). But these requests for edits “came months after the paper had already been accepted post peer review,” as Wright pointed out to me in a Twitter direct message. “This is not at all the normal process of peer review.” That is, after Wright and Khoo had made the requested edits and the paper had been accepted, a whole host of new edits were requested. Moreover, these requested changes were couched, by the editors of the journal themselves, in explicitly political terms: “Given how sensitive your key topics are -i.e. religion and violence - we need to be very careful about how specific issues are addressed, framed and received in your piece,” that email went. “In the wake of the Christchurch shootings, we are particularly aware of how important all our words are, especially those penned by our authors.” Lang presents this as normal, but it is not.

Brunton also sent Wright an email expressing displeasure at the idea of this story receiving media attention:

Dear Joshua

Our Corporate Communications team are in contact with Jesse Singal who is writing an article for the New York Magazine after you complained to him that you felt unreasonable changes were being requested of you and Yuelee, after your paper had already been accepted for publication.

Are we to assume then that you no longer want your article published in CVIR?

Our Corporate Communications team have sent on all requested papers by Jesse to him. We have also highlighted that the changes requested of you have in fact been made and that the piece has been accepted for publication. In our view, there really is no story here but if Jesse does have his piece published, I don’t believe you will want to have your article associated with the Journal.

Please can you confirm at your earliest convenience?

Kind regards

Gillian

Wright sent a curt reply that read, in part: “You are not to assume that. The paper has now been accepted twice and should be published as accepted.”

To which Brunton responded:

Thanks Joshua

We just wanted to be sure. Jesse has indicated he is sympathetic to your claims so we can only presume that if published, his article will aim to undermine the academic integrity of the Journal and in turn, perhaps the integrity of those articles already published in it.

You seem happy that your article will not be affected by Jesse’s story so we will publish as scheduled.

Kind regards

Gillian

I’m certainly sympathetic to Wright’s claims, but that’s because he forwarded me an email in which the editors of an academic journal suddenly introduced a host of new, last-minute edit requests — many of them a bit confusing or confused — to the authors of a paper that had already been accepted for publication, and specifically cited political concerns as a reason for doing so. My aim here isn’t to “undermine the academic integrity of the Journal,” but rather to amplify what strikes me as an interesting and telling story about what happens when politics and research collide in unhealthy ways.

Whether or not Wright responded with the appropriate degree of frustration and the proper tone, the fact remains that according to the editors of CVIR itself, the requested changes to the manuscript were, in fact, political. Here’s where the story likely would have gone a lot differently 20 or 30 years ago. Back then, Wright couldn’t have made his case directly to Twitter, and couldn’t have posted his preprint online for the world to see, making it clear that there isn’t anything unusual or particularly controversial about the paper in the context of its area of research (which there doesn’t appear to be).

In short, Wright had a bit more power than he would have had in the past, relative to the editorial gatekeepers he saw himself as being up against. Even without my decision to write up this incident in this newsletter, he would have been able to draw a fair amount of attention to it via social media, and to point to the paper itself and say “This is too politically incorrect to publish?” rather than force everyone to take his word for it in a he-said, they-said situation. It feels like a slight rebalancing of things that gives academics — particularly those who don’t have much clout otherwise — a bit more power than they used to have.

Questions? Comments? Religiously or secularly inspired threats of violence? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal. The lead image comes from Wikimedia Commons.