Here’s More Evidence That Youth Gender Medicine Researchers Might Be Hiding Unfavorable Data From The Public

Thanks, Illinois Freedom of Information Act

I hope people realize that when I complain about the lackluster quality of youth gender medicine research, there’s a much bigger issue at stake: something I’ve been concerned about for years, and that was a large part of my motivation for writing The Quick Fix. That issue is, simply put, whether we can trust science to produce accurate findings, and whether science is willing to allow external critics to question those findings.

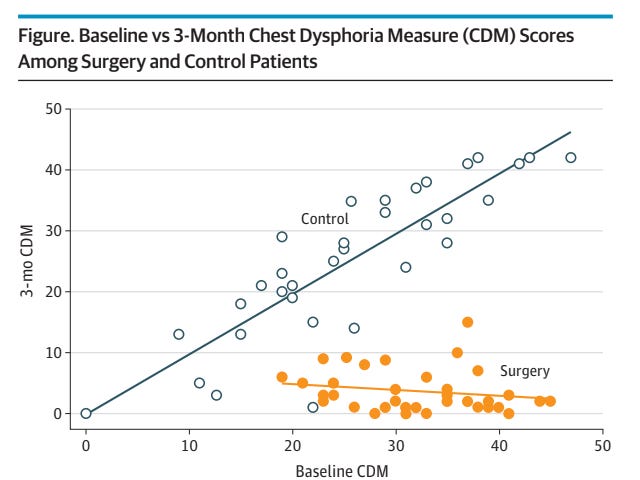

Let me use a very specific, ongoing example from youth gender medicine that nicely sums up this entire gigantic problem. Back in October I published an article about a JAMA Pediatrics study following up with a group of young people aged 13 to 24 three months after they got double mastectomies to treat their gender dysphoria. The most impressive-seeming finding came in the form of a reduction in the subjects’ scores on something called the Chest Dysphoria Measure (CDM), which, as the name suggests, is supposed to measure chest dysphoria.

If anything, I may have given short shrift to the magnitude of the reductions in participants’ CDM scores. Check out this chart from the study:

You can ignore the white circles, which represent members of a very strange “control group” that didn’t get surgery (the researchers openly admit that the control group differed from the treatment group in various ways — this means we really can’t make anything of any subsequent differences in the outcomes between the two groups). Those orange dots represent young people who got double mastectomies. The x-axis represents their baseline CDM scores, out of 51 points, and the y-axis represents their scores three months later. As you can see, a lot of the young people who got surgery saw their scores reduce 20 or 30 or 40 points. Hell, four of the subjects saw their scores drop all the way to zero out of 51. Zero!

But there’s really no way to know whether we should care about these seemingly huge improvements. As I pointed out, this unvalidated instrument seems to consist, in significant part, of different ways of asking someone whether they presently have breasts. It would be hard for someone’s score on it to not go down, in other words, after a double mastectomy. On top of that, I noted that what scant research is available on the CDM does not suggest it correlates all that meaningfully with other, validated measures of mental health (and even if it did, as an astute commenter pointed out, that wouldn’t necessarily suggest a causal relationship in which reducing someone’s CDM score led to reductions in anxiety, depression, or whatever else).

Given that this is major surgery being performed on young or very young people, where were the validated mental health measures evaluating outcomes like anxiety, depression, or suicidality? “[T]he complete absence of these measures in the study itself made me wonder if maybe the researchers had collected this data at baseline but simply chose not to report it because the trajectories were not what they wanted,” I wrote at the time. I reached out to the authors to ask and didn’t hear back, which certainly didn’t allay my concerns.

I remained curious about this study months later. In late January, I published this piece pointing out that a much-touted New England Journal of Medicine study supposedly showing that hormones improved trans kids’ mental health failed to report on six of the eight variables mentioned in its pre-registered study protocol. That study was something of an exception, because often study protocols are not published publicly, meaning we are forced to take researchers at their (usually implicit) word that they are not hiding unfavorable data. In February I sent an email to the University of Illinois–Chicago Institutional Review Board address to see if I could get hold of the approved IRB paperwork for the JAMA Pediatrics study. I got a friendly call from a PR person at the university, explained what I was looking for, and never heard back. (Update: I missed an easier way to get some of this information! See Addendum at the bottom.)

Luckily, I had learned along the way that sometimes these documents can be obtained via Freedom of Information Act requests. The short and oversimplified version is that when at least one of the coauthors of a study works for a public institution and/or the study was in part federally funded, you might be able to turn some stuff up. In this case, since a public university, UIC, was involved, I filed an Illinois Freedom of Information Act last month, focusing on that institution’s Institutional Review Board office. My goal was to get as much of the approved IRB paperwork as possible.

The University of Illinois sent me only a fraction of what I was asking for. The research protocol and other material couldn’t be sent over, they said, because it’s exempt from FOIA requests “under the Illinois Medical Studies Act.” We’ll get back to that in a bit. But the office did send over some of the consent forms for the study that participants and their parents had to fill out.

And there was some interesting stuff in there. First, here are the contents of a box titled “WHY IS THIS STUDY BEING DONE?” (bold in the original):

This research study aims to understand the impact of ‘top surgery’(mastectomy and chest masculinization) on gender congruence, gender dysphoria, chest dysphoria, and other domains of quality of life.

Gender congruence is the degree to which you feel that your body and life match your gender identity. Gender dysphoria is the distress you may feel from your body not matching your gender identity. Finally, chest dysphoria is the distress you may feel from your chest not matching your gender identity[.] We want to see how top surgery changes all of these feelings for you.

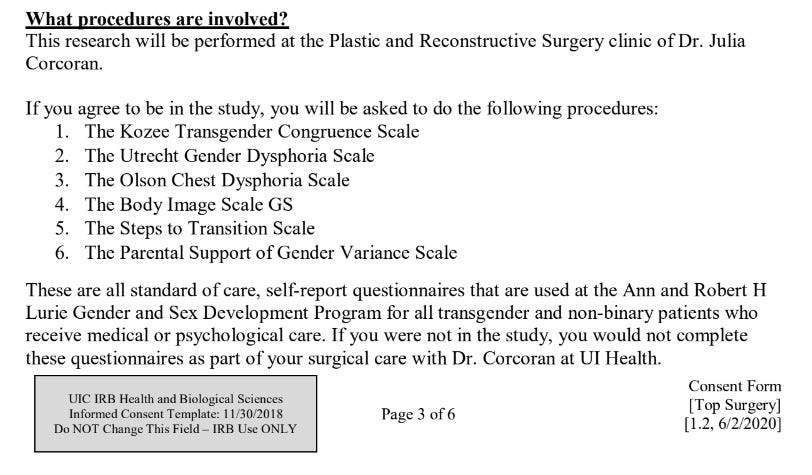

The consent form also lists the instruments the participants will be filling out:

If you agree to be in the study, you will be asked to do the following procedures:

1. The Kozee Transgender Congruence Scale

2. The Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale

3. The Olson Chest Dysphoria Scale

4. The Body Image Scale GS

5. The Steps to Transition Scale

6. The Parental Support of Gender Variance Scale

. . .

If you enroll in the study, you will complete all six questionnaires prior to your surgery. You will do this in the privacy of a clinic room during one of your pre-operative visits. You will then complete questionnaires 1, 2, 3, and 4 three months and one year after your surgery.

So this paperwork makes it clear that the researchers viewed chest dysphoria and gender dysphoria as two separate variables worth measuring with two different scales — the aforementioned Chest Dysphoria Scale (unless I’m badly missing something, this is used interchangeably with Chest Dysphoria Measure, or CDM) and the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale. And both of these instruments were supposed to be administered during all three waves of data collection: before surgery, three months later (the data underpinning the present study), and one year later (a yet-to-be-published study).

The UGDS is an established, validated scale that has been in use for quite some time. While one could reasonably argue that it isn’t as useful as other, better established mental health instruments that measure symptoms like anxiety and depression for determining whether we should be giving young people double mastectomies to treat their GD, it’s miles ahead of the CDM.

Guess where the Utrecht GD Scale data is in the published paper? Nowhere, that’s where. The scale isn’t even mentioned in the published paper. This is from the abstract:

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Patient-reported outcomes were collected at enrollment and 3 months postoperatively or 3 months postbaseline for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the Chest Dysphoria Measure (CDM). Secondary outcomes included the Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS) and Body Image Scale (BIS). Baseline demographic and surgical variables were collected, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to estimate the association of top surgery with outcomes. Probability of treatment was estimated using gradient-boosted machines with the following covariates: baseline outcome score, age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, insurance type, body mass index, testosterone use duration, chest binding, and parental support.

You’ll notice that the point of the study has shifted between the consent forms and the final publication. To paraphrase the researchers:

In the run-up to the study: “We’re interested in measuring gender congruence, gender dysphoria, chest dysphoria, and body image.”

Describing the study after it was published: “We were interested in measuring gender congruence, chest dysphoria, and body image.”

(Edit: I meant “gender congruence,” not “transgender congruence” as I originally wrote in the previous two sentences.)

So the researchers stated, in their consent forms (and presumably study protocol), that they were interested in measuring gender dysphoria, told the kids in the study they’d fill out surveys gauging their gender dysphoria, and collected this data — and then published a study that doesn’t mention this measure as a variable of interest. Huh?

I find this very weird, and I suspect that the researchers simply disappeared the variable because it didn’t move in the direction they wanted. But there’s simply no way to know for sure. The researchers won’t answer very basic questions about their methodology. Julia Corcoran, the UI plastic surgeon and study coauthor listed on the consent forms, didn’t return a request for comment, nor did her university’s press office, nor did the press office at Northwestern University (where most of the study’s authors are based), nor did Sumanas Jordan of Northwestern, the listed corresponding author. Remember that I reached out to some of these folks for comment before I initially wrote about and criticized the study — I was hoping they could answer my questions about it.

Meanwhile, the University of Illinois, a public institution funded by taxpayer money, won’t provide the documentation that would help us determine how suspicious we should be about the absence of this data from the published paper. Apparently it can’t, because of the Illinois Medical Studies Act Records law. Does that law actually exempt the paperwork in question? I dunno. I read the relevant brick of a paragraph and couldn’t see how it could possibly be meant to apply to this sort of situation, but of course as a non-lawyer, my opinion on this is barely better than worthless. I could definitely be wrong on that. (Correction: As if to prove I am not on solid footing here, I got the name of the law in question wrong here. I was right the first time: It is the “Illinois Medical Studies Act,” which you can read more about here.)

But am I, an independent journalist, going to hire an attorney who is an expert on the Illinois Freedom of Information Act and spend as much money as it takes —probably four or five figures — to make sure the University of Illinois hands over every last page of paperwork to which I am entitled? Of course not. Because the researchers did their job in an obfuscatory manner, all we can do is speculate, while they enjoy the professional benefits of a high-profile publication on a hot-button issue that got some glowing media coverage.

***

It doesn’t matter whether the subject is youth gender medicine or the implicit association test or cancer research or whatever else. If researchers aren’t transparent about their methods and won’t answer basic questions about those methods, they are not entitled to our trust. Full stop. We’ve been through this so many times, at this point, in so many different areas of science. There have been many replication crises. It’s crazy that in 2023, researchers are still allowed to hide so much of their work.

I really can’t overstate what a threat to science this is. This paper was published as part of a giant social and professional ritual that includes getting IRB approval, recruiting patients, collecting data, working with peer reviewers, and so on. The power of that ritual is supposed to be that the finished product — the research that is published — reflects a different, higher-quality type of knowledge than speculation or opinion or demagoguery. But for all we know, it might not be much better than that.

What is the point of having science if it is this shrouded in mystery and uncertainty? Of course there will always be some uncertainty in science; it wouldn’t be science if it claimed otherwise. But there are some types we should tolerate and some we shouldn’t. We should tolerate measurement error and other types of inherent fuzziness; there will never be a perfect way to gauge, on the basis of self-report (or anything else), someone’s level of gender dysphoria. But we should not tolerate variables disappearing and/or being file-drawered in this manner. It’s a very low bar to clear, and an absolutely vital one given that we are talking about a very vulnerable population.

This should exasperate you. It should exasperate you if you’re skeptical of these treatments, but it should also exasperate you if you favor them. Either science takes these kids’ lives and treatment decisions seriously, or it doesn’t. Disappearing a key variable without any explanation why could not be a clearer signal that at root, this was not a serious effort to understand the effects of these surgeries.

Addendum: Despite looking pretty deeply into this study, I missed something fairly obvious, which is a ClinicalTrials.gov page associated with this study that does lay out the researchers’ hypothesis: “The investigators hypothesize that masculinizing top surgery (e.g., mastectomy and chest masculinization) leads to an improvement in self-report chest dysphoria, gender dysphoria, and gender congruence in assigned-female-at-birth, transgender and non-binary youth and young adults.” Gender dysphoria is listed as a “secondary outcome.”

Apologies — I am still new to chasing down this sort of information. But all my arguments about transparency stand, because there’s still no explanation anywhere as to why this variable disappeared. Thank you to the reader who emailed me to note the existence of this page.

Questions? Comments? The study protocol? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com. Image (recycled from my last post on this): “Surgeon adjusting glove in operating room - stock photo” via Getty.

Make sure to see my Addendum -- some (not all) of this information was available on a government website, it turned out.

This seems like a growing problem with gender affirming care. Assessing whether an intervention “works” can be thought of in two ways: did removing breasts make the patient feel better because they no longer have breasts, and therefor it “worked”? And then the question of whether the mastectomy worked in terms of reducing gender dysphoria and/or improving general mental health.

So often it seems like these studies say, It worked! But they only assess the first question, and then claim it answers the second question, as if the one obviously follows the other.

But does it?

Anecdotally we hear a lot about an incessant, almost Sisyphean quest to find the next thing that will assuage GD--first the blockers, then the hormones, then a suite of surgeries, always looking for the next one that will make them pass better or maybe make them feel that they are more “truly” the target sex.

I think the difference between question one and question two is profoundly important, and the latter is probably the one that matters the most: if an intervention doesn’t resolve dysphoria and/or improve the mental health of the patient, what’s the point?