Freddie deBoer Let Me Resurrect Three Of His Excellent Essays And You Should Read Them

Welcome to the Planet of Cops, where everyone is a snitch

(“They should have sent… a poet…. It’s so beautiful.”)

I am worthless in the kitchen, and for a long time I viewed the task of baking my own bread the same way I viewed the task of, say, creating a large sculpture of myself swinging a sword at a monster: cool in theory, but there was just no way someone like me could pull it off. But then I bought a bread machine on a whim thanks to an online deal. It worked: I produced actual bread I could and did eat, and it wasn’t even that difficult to do. Then I discovered the New York Times’ famous No-Knead Bread recipe, adapted from Sullivan Street Bakery here in New York, which, again, worked: I followed the instructions and about 22 hours later (lots of time waiting for the dough to rise), out popped some bread. A little flatter than I would have liked, but very tasty. Weird! I actually made bread from scratch.

Finally, I discovered Jenny Can Cook’s Faster No Knead Bread recipe (video here), which has been my go-to ever since. The bread poofs up more, and it tastes better — all despite taking a lot less time. Yes, yes, I realize I am still but a bread-neophyte and haven’t come close to doing all the fancy things people who bake sophisticated bread do (like, uh, kneading dough for even one minute). But it’s still been a lot of fun. And I guess if there’s a lesson or a point here — really I was just looking for an excuse to post the above photo of one of my bread-children — it’s that as soon as you demystify something by just doing it, you might find you aren’t quite as terrible at it as your utter, pathetic haplessness in that general domain had previously led you to believe you would be.

I should give inspirational speeches to kids or something.

Admin Stuff

None! Well, other than deciding whether to include the subhed “Admin Stuff” when I don’t have any actual admin stuff to mention. I’ll answer this question during a 10-part series in my upcoming newsletter-administration spinoff newsletter, Talkin’ Newsletter Administrative Decisions (With M’Pals). Keep an eye out.

Freddie DeBoer Let Me Resurrect Three of His Essays and You Should Absolutely Read Them

There aren’t a lot of people who Get It like Freddie DeBoer does. He’s able to pack a huge amount of insight into politics, human nature, and the more frustrating aspects of online culture into tight, expertly constructed essays and blog posts. He’s very much a leftist, but because he’s such a smart and clear writer, over the years he has attracted enthusiastic fans from across the political spectrum — not to mention a group of dedicated and frequently disingenuous haters on the left who can’t stand the idea of someone critiquing our side as cuttingly as he does.

Unfortunately, deBoer pulled a lot of his best essays offline. I don’t know why, but he has written openly and honestly about his severe struggles with mental illness, and he left social media because of what it was doing to him, so that might partly explain it. (Lest I be accused of whitewashing, it should be added that he sometimes lashed out at others online, and in one instance made a serious false accusation he later retracted and apologized for.) Lately I’d been thinking a lot about a few of these essays, still available on internet-archive sites, and found myself reading and sharing them with others over and over and over. They’re so good. And frequently quite prescient.

Yesterday morning I emailed deBoer and asked him if he had ever thought about republishing them, or allowing someone else to. He gave me permission to repost anything I wanted that had been archived, so I grabbed my three favorites and they’re now up on Medium. You should definitely read “of course, there’s the backchannel” (every time I read that one it gets truer and more worrisome), you should definitely read “the Iron Law of Institutions and the left,” and you should definitely definitely read “Planet of Cops,” which includes this paragraph:

A cop culture is one where a mob forces a company to patch its game because the treatment of video game parrots is somehow deficient. Do you buy that narrative at all? Do you think any single human being is so fucking daft as to believe that lots of children are going to be inspired by Minecraft to feed their real parrots real chocolate chip cookies? Or do people like being cops? Do they like being in a position to make demands? Do they like lazily threatening people, “nice company you have here… wouldn’t want it to get embroiled in some controversy”? People are alienated and worn down and hopeless, and so they see their opportunity to finally be the one pulling over somebody else’s car, lazily tapping the glass with their flashlights. “I’m the one in charge now,” he thinks, as he sends an email to somebody’s boss over a Facebook status he doesn’t like.

We need more Freddies deBoer. Especially now.

Here is a Really Interesting Graph About How Biased Our Brains Are

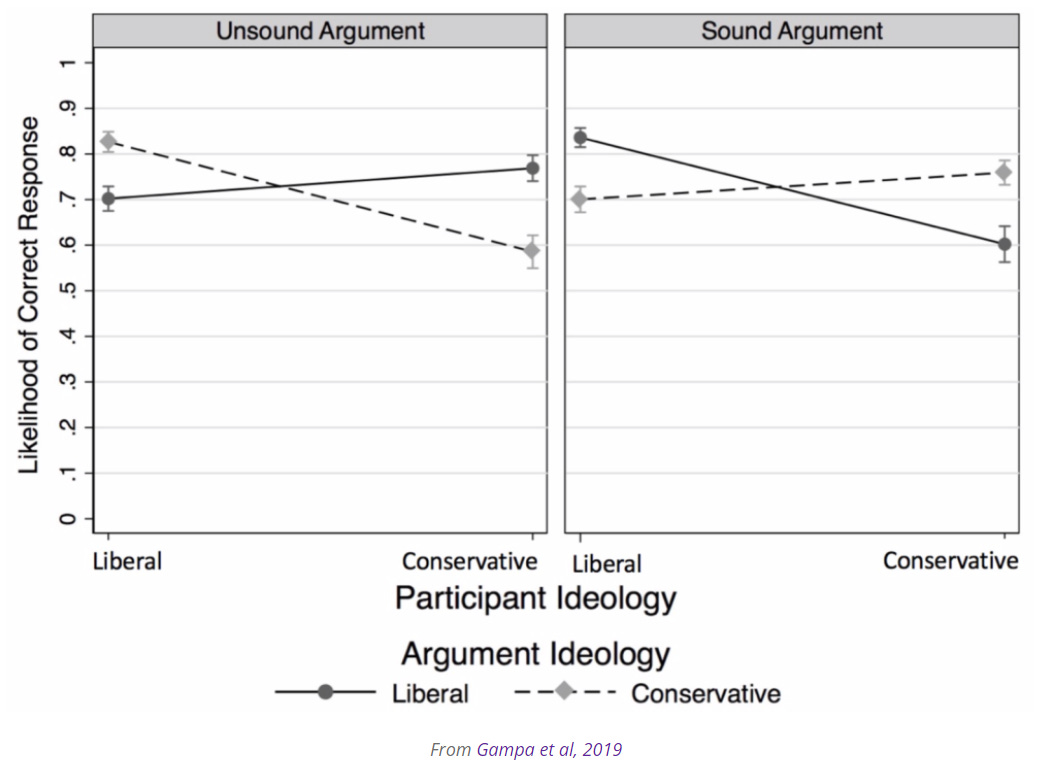

I have a side-gig as a contributing writer at the British Psychological Society’s Research Digest website, and yesterday the site published my writeup of such a cool article. It included this graph which might take a minute or two to parse, but which is, in my opinion, worth dwelling on:

Click here for the article itself, but basically, what this graph shows is that participants in it had more trouble accurately determining whether arguments were logically formed when the conclusions of those arguments clashed with their personal politics. The article’s three experimental studies relied on syllogisms, which are series of statements like this one:

(1) All things made of plants are healthy. [premise]

(2) Cigarettes are made of plants. [premise]

(3) Therefore, cigarettes are healthy. [conclusion]

This is a valid syllogism. Given the rules of the syllogism-game, it doesn’t matter whether cigarettes are healthy in real life (I do remember reading somewhere that they are not). What matters is that the conclusion logically follows from the premises.

In the study, when syllogisms had conclusions likely to be met with disagreement by liberal or conservative subjects (“Marijuana should be illegal” was one conservative-leaning conclusion, and “Abortion is not murder” was one liberal-leaning one), those subjects were more likely to mess up and inaccurately describe valid syllogisms as invalid, and invalid syllogisms as valid.

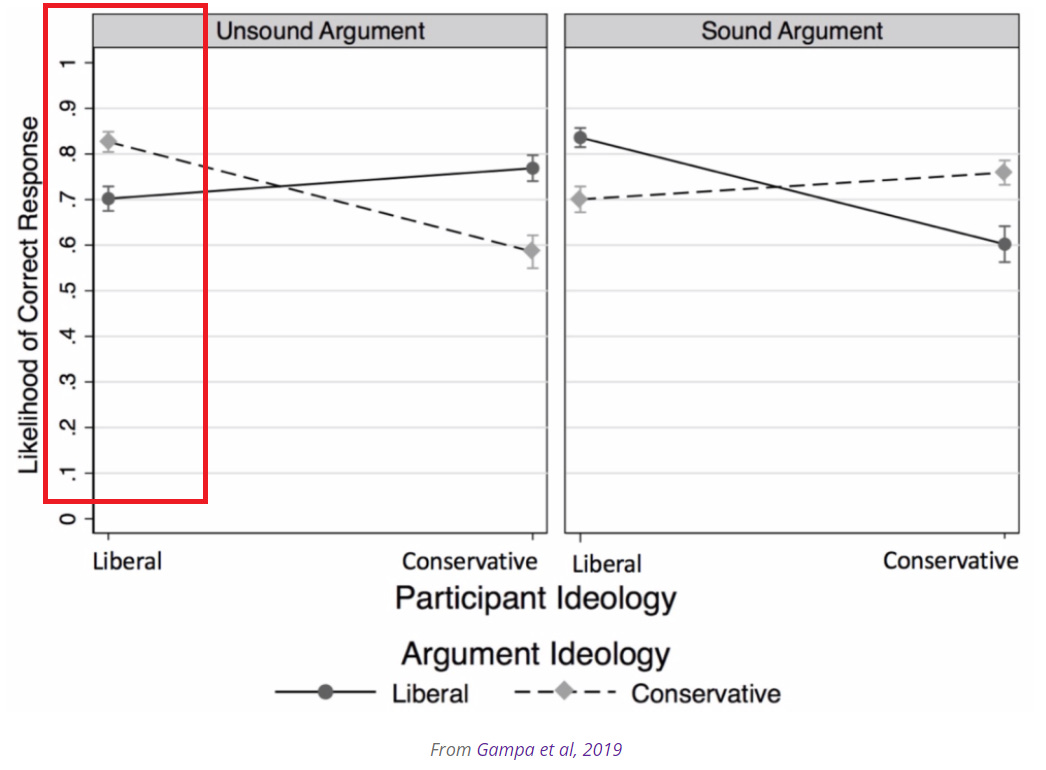

At the risk of overexplaining the graph — it took me a little while to fully get it, since there’s a fair amount going on — it might be easiest to just look at its very leftmost part: That part shows how likely it was for liberals respondents to accurately determine that unsound arguments with liberal and conservative conclusions were, in fact, unsound.

As you can see, there was a greater than 10 percentage-point gap: Liberal participants were a lot better at correctly calling foul at unsound conservative arguments than unsound liberal ones. It’s like they were more likely to wave through the liberal ones because they felt right, and more likely to closely inspect the conservative ones because they felt wrong. And elsewhere on the graph, similar, corresponding patterns hold for all the other types of arguments. This finding lends support to a heaping pile of other research on the general subject of motivating reasoning, or our tendency to discount evidence that would threaten beliefs we hold or want to hold; it suggests that both politically friendly- and unfriendly-seeming conclusions might actually disrupt our reasoning abilities.

As the authors explicitly note, their studies weren’t designed to be able to tell which side does it “worse.” I think that’s a really complicated question and one which would generate different answers depending on how exactly it was phrased and tested and so on. Complicating matters further, and as I wrote last summer, I do think some of the past research on conservative psychology itself exhibits signs of bias, possibly the result of the fact that the vast majority of the researchers who have conducted it over the years have had politics in the same ballpark as my own.

But I also think it’s a little bit beside the point to talk about whether one side is, on average, in some significantly zoomed-out way, more susceptible to bias than the other, especially if the question is what you or me or any other individual should take from a graph like this one. There is overwhelming, overwhelming evidence that it isn’t liberal or conservative or libertarian brains that are biased, in the general sense: It’s brains that are biased. And there are so many examples of members of every conceivable political tribe making catastrophic judgement errors as a result of bias that everyone should be on the lookout for it. Research like this helps untangle these dynamics; it helps keep us all vigilant.