Aurora James, The Designer Of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's "Tax The Rich" Dress, Said She Started A 501(c)(3) To Help Black Businesses. Her Organization Is Not A 501(c)(3)

More trouble for the fashion entrepreneur

Recently the New York Post reported that Aurora James, the Canadian fashion designer and entrepreneur behind the “TAX THE RICH” dress and bag Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez sported at the Met Gala, “had unpaid [tax] debts dogging her in multiple states,” owed tens of thousands of dollars in unpaid rent, and was accused anonymously by one former contractor and one former intern of exploitative labor practices.

James has also claimed, for more than a year, to have founded a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization devoted to helping black business owners. But there’s no evidence the organization in question is actually a 501(c)(3), or that it is seeking to become one.

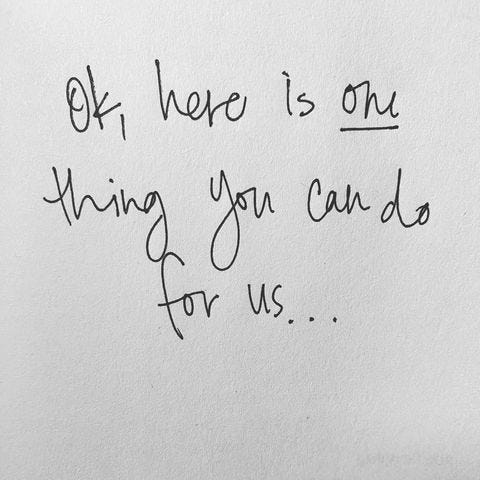

This story goes back to May 29, 2020, four days after George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. James posted to Instagram a photo of a handwritten note reading, “Ok, here is one thing you can do for us...” The photo was accompanied by text calling out major retailers like Target, Whole Foods, Home Depot, and others for doing business in an exclusionary manner. James wrote: “I am asking you to commit to buying 15% of your products from Black owned businesses.” “So many of your businesses are built on Black spending power,” she continued. “So many of your stores are set up in Black communities.”

The post sparked what appeared to be a very successful campaign — a number of major retailers agreed to the pledge, generating glowing coverage of James and her activist efforts in outlets ranging from Vogue to The New York Times. James was even just named one of the 100 most notable people of 2021 by Time because of her activism.

There was a formal component to these efforts: In the wake of her Instagram post, James launched an organization called Fifteen Percent Pledge (archived version of the site here). “I posted it on a Saturday, we had a website launched by the following Monday, and were a 501(c)3 by Wednesday,” James told CNBC in 2020. (Disclosure: It’s behind a paywall, but I recently wrote a newsletter criticizing this effort and arguing that it seemed more likely to direct money and energy to black entrepreneurs who are already in comfortable financial shape — like James herself, who recently did an ad for Jaguar and launched a product line at Sephora — than the sorts of black businesses struggling the most right now, the vast majority of which were never in a position to seek shelf space at major retailers in the first place.)

Until very recently, FPP described itself as “a 501c3 non-profit advocacy organization urging major retailers to commit 15% of their shelf-space to Black-owned businesses. It offers large corporations accountability support and consulting services with the goal of advocating for and supporting Black-owned businesses.” Elsewhere on the site, FPP said it was “a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization calling on multi-brand retailers and corporations to dedicate 15% of their total purchasing power to supporting Black-owned businesses.” I copied and pasted all the above language last week, and you can also see it on the most recent Wayback Machine archive of the site, though that dates back a bit further, to mid-September. (For those unfamiliar with the term, 501(c)(3) is a tax status granted by the Internal Revenue Status to certain charitable organizations: A 501(c)(3) “does not pay income tax on its earnings or on the donations it receives,” explains Investopedia. “Also, any taxpayer donations may reduce a taxpayer's taxable income by the donation amount.)

Now those references to the organization’s tax-exempt status have been quietly removed. This occurred not long after I asked Fifteen Percent Pledge and its ostensible “fiscal sponsor,” Philanthropic Ventures Foundation (more on this soon), for proof that James had actually asought 501(c)(3) status for her organization.

James did register Fifteen Percent Pledge, Inc. as a domestic not-for-profit corporation in the State of New York — its listing is available here, and the timing lines up with her reference to having immediately formed a 501(c)(3) after the Instagram post went viral. Except the two are not the same thing. Forming this sort of corporation is indeed the first step in obtaining 501(c)(3) status, according to a law professor I spoke with who has expertise in this area and who did not want to be quoted by name commenting on a specific organization. But there’s a second step: After that, you need to “Apply to the IRS for recognition of 501(c)(3) status,” the law professor wrote in an email. “Only churches and very small organizations (under $5k in annual revenue) can skip this step and ‘self-declare’ their exemption.

All the available evidence suggests Fifteen Percent Pledge either never took this step, or did and was rejected by the IRS, or that something else went wrong and the organization isn’t even on a trajectory to become a 501(c)(3). That’s really the only way to explain the current timeline of events.

If Fifteen Percent Pledge isn’t a registered 501(c)(3), where do donations to it go? To Philanthropic Ventures Foundation, which is a legitimate 501(c)(3) (Guidestar listing here). It is an organization that “has consulted with over 400 community and family foundations in the United States, Canada and Europe. The focus is on creative grantmaking, streamlined operations and community impact.” At various points on FPP’s website and during the donation process — I donated a few bucks to see what the receipt would look like — FPP mentions this relationship. One portion of the website, for example, notes that PVF “serves as the fiscal depository for 15 Percent Pledge.”

There’s a version of this arrangement which is oftentimes kosher: If a would-be 501(c)(3) is awaiting its official approval from the IRS, which can take months or sometimes even longer, it can have another nonprofit accept its funds in the meantime. In this arrangement, which is generally referred to as a “fiscal sponsorship,” that organization will usually skim a small administrative fee and disburse the funds to the new organization while it is in its nascent phase. So if Fifteen Percent Pledge were an actual 501(c)(3)-in-progress, that would explain all of the above.

When I reached out to Fifteen Percent Pledge and Philanthropic Venture Foundation about the fact that there didn’t appear to be any evidence the former was incorporated as a 501(c)(3), I was referred to a couple of staffers from the public relations firm BerlinRosen. They were helpful and responsive and last Tuesday one of them sent me this statement from PVF:

The Fifteen Percent Pledge is incorporated in New York State Under Section 402 of the Not-for-Profit Corporation Law, with processing EIN number 85-1243386.

The Fifteen Percent Pledge is fiscally sponsored under the Philanthropic Ventures Foundation's 501(c)(3), under PVF's Federal Tax ID of 94-3136771.

Fiscal sponsorship is a common practice with a long history, to support new charitable programs while they await federal 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.

All of which is true, but only really applies here if Aurora James actually applied for 501(c)(3) status for Fifteen Percent Pledge. Otherwise, she and her organization were collecting money on a false pretense, given their repeated claims their organization is an established 501(c)(3) . So I followed up. “Thanks,” I wrote in a response email to the BerlinRosen rep. “[A]ll that's missing on my end pertains to this part: ‘to support new charitable programs while they await federal 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status.’ Can I just get confirmation Fifteen Percent Pledge has actually applied for 501(c)(3) status, as well as the date that occurred and if there's been any response from the IRS?” “Working on it,” responded the rep just an hour later. (Update: I added the language in bold to clarify what I meant by “only really applies,” since a couple people thought I was saying the sponsorship relationship itself was illegitimate, which wasn’t my intention.)

But that email, a week and a half ago, was the last I heard from her, or from anyone at BerlinRosen. I sent (polite) followup emails to her, to higher-ups at PVF, and to James’ personal publicist. Nothing. And then, sometime in the last week or so, Fifteen Percent Pledge quietly scrubbed from its website the claim that it is a 501(c)(3). (It still mentions PVF being its sponsor, and PVF, for its part, still lists it as one of the “designated funds” it sponsors “that do not yet have their tax-exempt status but are otherwise ready to commence their charitable work.”)

The most likely explanation here is that Fifteen Percent Pledge never filed for 501(c)(3) status, or it did but was subsequently rejected. If that isn’t the case, why wouldn’t any of the organizations or PR folks involved just pass along the documentation I asked for? Why would FPP strip these mentions from its website shortly after my inquiry? If it were just a matter of the organization having jumped the gun a bit while its application was pending, it could have replaced the website language with something like “We are currently seeking 501(c)(3) status,” which is phrasing you’ll sometimes see other groups use.

My theory — and it is just a theory — is simply that Aurora James didn’t know the difference between registering as a nonprofit corporation with the State of New York and obtaining 501(c)(3) status from the federal government. That would neatly explain why she claimed to have immediately founded a 501(c)(3) after the viral Instagram post, despite the fact that it takes quite some time (and a fairly involved application) to gain this status. And I should be clear that ignorance or disorganization are much tidier explanations here than actual malice or fraud. After all, the donations have been going to an actual 501(c)(3)! It isn’t as though she herself pocketed them, or anything like that.

On paper it’s Philanthropic Ventures Foundation’s responsibility, as the sponsoring organization, to make sure Fifteen Percent Pledge’s ducks are in a row. The money that goes to FPP to, for example, pay staffers — and FPP appears to have staffers and to be seeking to hire more — flows first through PVF. So, given that PVF is a legitimate organization, it would be interesting to understand exactly what’s going on here if, as all evidence indicates, FPP isn’t on track to become a 501(c)(3). (Feel free to email me if you have information about any of this, of course.)

One last point worth noting: It’s by no means a slam dunk that even if James sought 501(c)(3) status for her organization, she would obtain it. The aforementioned professor told me in an email that she was skeptical, based on Fifteen Percent Pledge’s website, that it would qualify under the IRS’s rules:

Based on their website, I'm doubtful that 15 Percent Pledge is operating for charitable purposes that would make it eligible for 501(c)(3) status. They appear to (1) promote Black-owned businesses, (2) provide "consulting" services to big companies on how they can meet their pledge (it's unclear whether they charge for this service), and (3) provide a jobs board for companies that they deem worthy (like Sotheby's). Serving private businesses is usually not considered a charitable activity unless it's designed to alleviate poverty (e.g., helping low-income entrepreneurs), combat neighborhood deterioration (e.g., inducing a business to open in West Virginia and provide jobs), or eliminating prejudice and discrimination. The last one is tricky because there are a few IRS rulings from the 70s and 80s saying that helping minority-owned businesses is charitable due to pervasive discrimination in business lending, etc., but it's not clear whether these decisions would come out the same way today. It might take an equity approach (Black-owned business underrepresentation on shelves automatically signifies discrimination) or it might insist on an individualized determination that the beneficiary has faced discrimination or is otherwise disadvantaged.

Another law school professor, also an expert in this area, agreed with this professor’s assessment after I sent it to him. “If what they do is as described, I think the expert is correct,” he wrote in an email. “This description does not fit easily into section 501c3. There could be other facts of which I am unaware.”

Again: This does not look like an intentional scam. But it’s certainly fraught to tell people you have founded a 501(c)(3), and to collect donations for it, when that is not the case — it’s sloppy and misleading at best.

If James or any of the organizations involved can provide more information about what’s going on here, I’ll be happy to update this post.

Questions? Comments? Ideas for nonprofit scams we could start together? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

Image credit: BROOKLYN, NEW YORK - SEPTEMBER 08: Aurora James attends the Christian Dior Designer of Dreams Exhibition cocktail opening at the Brooklyn Museum on September 08, 2021 in Brooklyn, New York. (Photo by Ilya S. Savenok/Getty Images for Dior).

> for proof that James had actually asought 501(c)(3) status for her organization.

Minor typo here.

There's been quite a bit of fraud in the post-Floyd everything. Are nonprofits/wannabe-charities usually this unscrupulous?

Boy, you really nailed her here… So you’re saying she’s collecting money for a non-profit that is going to a non-profit but it’s not the one that’s doing the collecting?