Against Detached Entitlement In Liberal Intellectual Spaces

A critique of an “Inside Higher Ed” column on affirmative action

Yesterday, Inside Higher Ed ran a column headlined “Affirmative Action Is Probably Dead: Now What?” In it, authors Antar Tichavakunda and Suneal Kolluri, researchers at the Universities of Cincinnati and Southern California, respectively, “review the options for those who worry about the Supreme Court’s possible decision,” as the subheadline put it.

I try to be somewhat sparing with how often I use this space to respond to a single column or news article, but sometimes it’s useful to do so. In this case, the column in question reveals certain shortcomings in liberal intellectual spaces that deserve to be addressed.

The authors’ premise is that opposition to affirmative action is itself racist. They don’t say so explicitly, but they’re pretty clear:

Our line of thinking here is inspired by [critical race theory godfather Derrick] Bell’s scholarship—especially his paper “Racism Is Here to Stay: Now What?” About his seemingly pessimistic title, Bell said, “far from an invitation to ultimate despair,” acknowledging that racism is here to stay “can serve as an opportunity for new insight, more effective planning.” We feel similarly about the demise of affirmative action. We need to start thinking differently about how to counteract the inevitability of setbacks in efforts toward racial justice.

They go on to explain that “Bell urged activists to adopt a stance of ‘racial realism’—assuming that racism is a permanent feature of life in the United States. This stance compels us to think creatively and strategically about how to counteract the inevitability of setbacks in efforts toward racial justice.”

I would question the utility of this framework in this particular setting. Yes, race-based affirmative action (let’s just call it RBAA so I don’t have to keep typing that) is likely to be dealt a crippling blow by a conservative-dominated Supreme Court set to hear a pivotal case on the subject this autumn, and yes, white people who feel racial resentment, and/or who are outright racists, are vehemently opposed to RBAA.

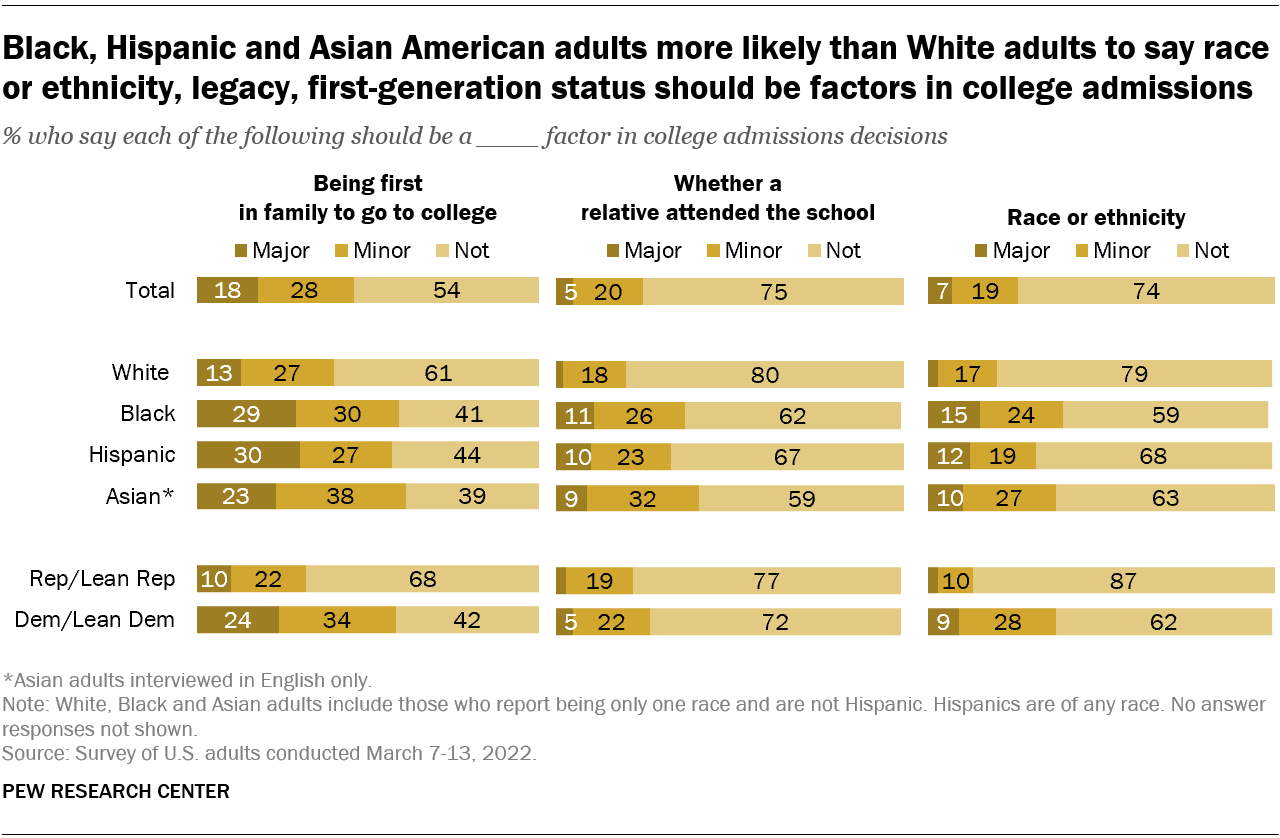

But these aren’t the only people who dislike RBAA. The fact is, it’s an unpopular policy, full stop. The racial group that most favors RBAA is black Americans, and even there, 59% say race should not be a factor in college admissions at all, according to Pew polling from earlier this year:

Among all other racial groups, the numbers are significantly worse. This is a policy that enjoys no broad support among anyone, and that includes the groups most likely to benefit from it.

Sometimes public opinion matters a lot, and sometimes it matters a little. In this case, at the end of the day it’ll be just nine Americans — the ones in the funny robes — who will decide the fate of RBAA. But of course, the policy’s mass unpopularity is also relevant. Take California, which has been the epicenter of many fights over this policy. There, opponents of affirmative action were able to use the state’s wacky referendum system to enshrine into the state’s constitution a ban on all forms of affirmative action in 1996. In November 2020, around the peak of the post–George Floyd racial reckoning, an attempt to repeal this amendment lost by 15 percentage points.

So even if RBAA didn’t face constitutional challenges, there’d still be the fact that, rightly or wrongly, people don’t like it. You’d think a column by two scholars very concerned about the potential extinction of this policy would make some reference to its durable unpopularity, and perhaps offer a strategy or two for convincing voters to feel more warmly toward it. They do neither: They present a flattened account in which supporting RBAA is supporting racial justice and opposing it is opposing racial justice. Never mind the fact that opponents of RBAA range from far-right white racists to… the average black voter.

It’s also noteworthy how little Tichavakunda and Kolluri have to offer in the way of substantive non-RBAA policies to address the lack of black (and to a somewhat lesser extent, Latino) students at competitive colleges. This is a really big, thorny problem that has existed for decades. At root, it comes down to the fact that black and Latino kids are simply less likely to be accepted into these schools if you use “traditional” metrics. As the University of Michigan put it in an amicus brief it filed supporting the pro-RBAA side of the SCOTUS case being heard this fall:

The University of Michigan has concluded that while targeted recruiting and outreach efforts, combined with emphasis on socioeconomic factors in admissions, are helpful in increasing attendance by underrepresented minorities, such measures are not themselves sufficient to secure the educational benefits of student-body diversity. While U-M’s efforts have attempted to expand the cohort of qualified racially and socioeconomically diverse candidates, the overall pool of potential minority applicants with competitive academic qualifications remains very small—both in absolute terms and relative to the number of qualified non-minority and wealthier applicants.

I’ve argued previously that people tend to stigmatize this sort of argument as itself racist, but that they shouldn’t. These numbers reflect, in part, the fact that certain groups have gotten a raw deal as a result of the nation’s very racist past and need more help to catch up with everyone else. It has nothing to do with being black per se — certain recent black immigrant groups are flourishing (those from Nigeria and Ghana in particular), doing better than many non-black ethnic groups, in part because they simply aren’t lugging this baggage around. It’s the subgroups that have been locked in intergenerational cycles of poverty that are the ones most likely to be shut out of higher education. It isn’t a surprise that a group that is numerically small (the United States is just 12.4% black) and whose ancestors were disproportionately likely to have been subjected to this sort of historical brutalization would have trouble competing for slots in competitive higher education settings.

Here’s where we can safely predict Tichavakunda and Kolluri will offer up some ideas for closing these gaps. It obviously won’t be easy, but you have to start somewhere, right? Sure enough, the authors reference the “deep historical inequities that constrain [marginalized individuals’] opportunities” and state their intention to “turn to two communities who have long served marginalized youth and who would benefit from expanded support toward racial justice: public high schools and minority-serving institutions of higher education.” They excitingly note that there are “promising developments in high schools [that] have potential to expand educational access and racial justice for marginalized communities.”

Good stuff! Let’s do this. Let’s dive into policy.

But then:

In states and school districts, ethnic studies is being implemented as a graduation requirement, mandating that all students consider race and racial justice as part of their high school curricula. The College Board has begun piloting an Advanced Placement African American studies course. Schools are implementing restorative justice practices, aiming to undo disciplinary disparities by race and ethnicity.

While these race-conscious curricula and policies are receiving staunch resistance in conservative states, universities committed to the ideals of racial justice might push back by requiring their applicants to think and act on issues of racial justice. Could racial equity be expanded by requiring all applicants to have taken an ethnic studies class or by requiring students to include in their application a statement on their commitments to racial justice? Though universities may soon be denied the ability to consider race in admissions, they can consider a commitment to racial justice as part of a holistic admissions process.

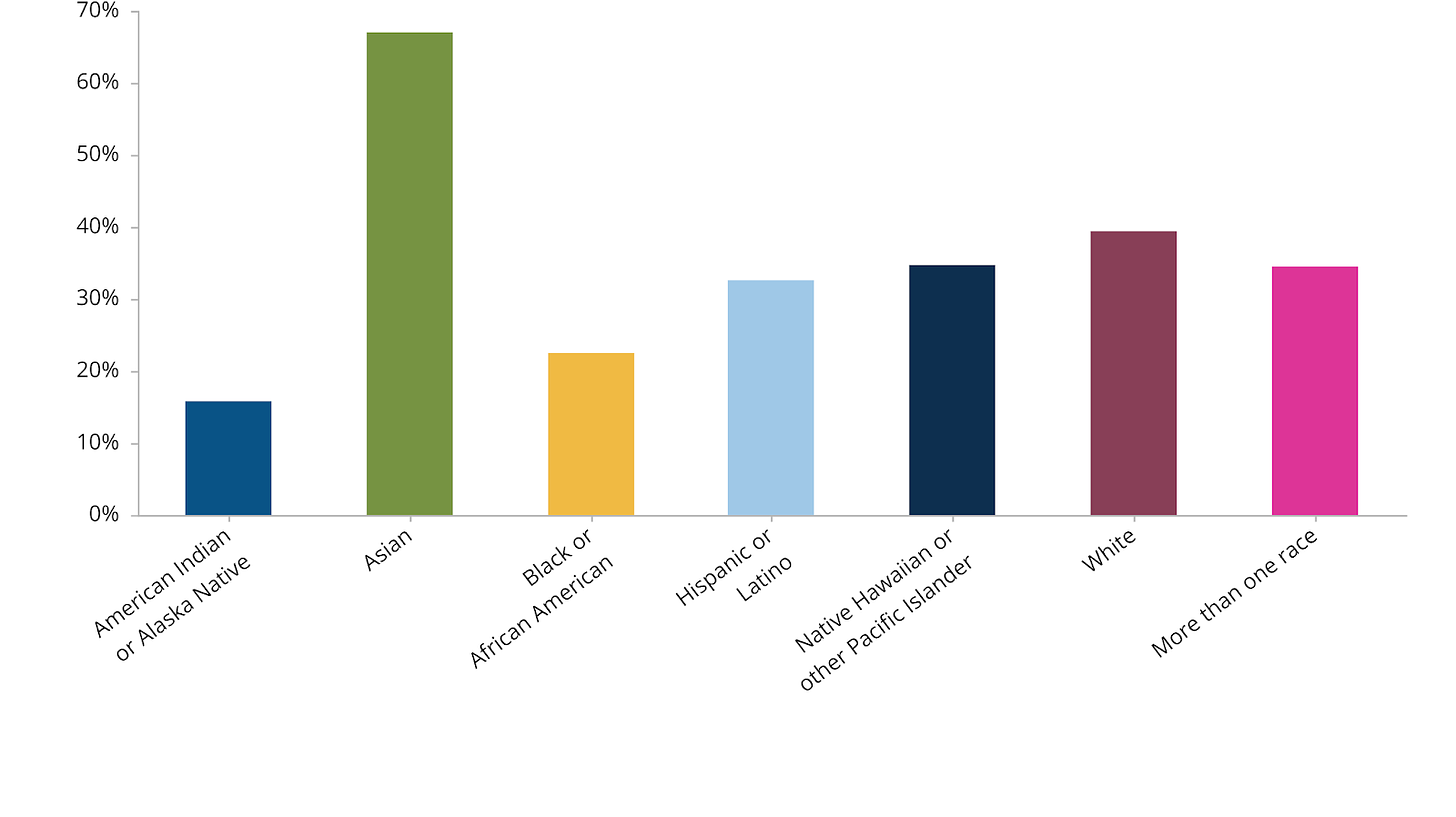

Very little of this makes sense. Yes, an AP African American studies course sounds like a great idea — there should already have been one. But how is this going to create a more competitive pool of black and Latino college students? Naturally, the chart of who takes AP classes roughly maps onto the chart of who succeeds in higher ed:

So if you introduce another AP class, whatever the subject, you’ll get… a group of disproportionately Asian and (to a lesser extent) white kids taking it, racking up college credit, and using that to jockey in the admissions game. It isn’t like by introducing a black-related subject, you’ll suddenly get more black students qualified to take and pass AP courses, because the question of who does and doesn’t enroll in college-level coursework as a high-school student is overdetermined, and sadly has a lot to do with factors which occur much earlier in life.

It’s a very similar deal with “requiring students to include in their application a statement on their commitments to racial justice.” We already know what would happen in a hypothetical race-blind admissions system that introduces this element: Kids in positions to “write” (read: have their parents hire someone to write for them) compelling admissions essays will pen searing, poignant, beautiful essays about their commitment to racial justice. These kids will be… the same kids already dominating college admissions. I mean, just imagine going to a poor black single mom hoping her bright 16-year-old will be the first in their family to go to college, but who is facing all the logistical and financial hurdles this entails, and telling her: “Good news: There’s a new admissions requirement, and your son will now be required to write about his commitment to racial justice.” Does this reflect 1) a realistic understanding of the challenges faced by such a family; or 2) a privileged person’s belief that a great deal of injustice would resolve itself on its own if only more left-wing politics were injected into everything? To believe that the introduction of this new criterion would help such a kid compete is to engage in rather rank essentialism.

Look, it’s not as though this column is completely devoid of decent ideas. Who would be against fighting genuine instances of unfairness with regard to school disciplinary policy? But even some of the substantive suggestions reflect a disconnect from how this policy controversy is actually playing out on the ground. For example, the authors suggest that “universities might partner with school districts serving students of color to expand the resources of those communities,” citing Yale and Stanford as two examples. But of course such programs already exist: Yale spends $5 million a year helping qualified New Haven public school students go to college. Perhaps this amount should be higher (Yale’s endowment is $42.3 billion), and perhaps such programs should be expanded, but to point to an elite university that already has such a program and to suggest they implement one points to a certain perfunctoriness to this whole column.

It was the last bit that annoyed me the most, though:

[W]e end this essay with a call to those who care about racial justice to struggle, to come up with creative ways to fight for a more racially just higher education, pre-emptively. Let us set the rules of engagement. Let those who oppose us—the conservative critics, the conservative wing of the Supreme Court and those beholden to white supremacy—let them catch up. What else can we dream up? Let us use new strategies until the court deems them unconstitutional and we start over again. Let us continue to struggle. Let us continue to resist.

I know this is more of a closing flourish than a meaningful argument, but it bugged me. “Let them catch up.” My dudes — you are losing. You have just laid out an entire column about how your preferred policy is on the ropes, teetering on the brink of being knocked out, possibly forever, and you’ve offered basically no substantive alternatives, and you haven’t even addressed the second-biggest political obstacle to race-based affirmative action after SCOTUS (its unpopularity). You finish a column like this?

There’s an ingrained breezy entitlement in some liberal intellectual spaces that mucks everything up. If people don’t agree with our preferred racial justice policies, it’s because they’re racist. Okay, whatever, they’re racist — what are you going to do about it? Ummmm, more ethnic studies? Wait, so your argument is that affirmative action is on its deathbed because society is too racist, but you think ethnic studies is part of the answer instead? Or what about if, like, rich universities gave money to poor kids? Okay, but isn’t that already a thing and don’t you worry that — Also: Let them catch up.

I don’t think this represents a very serious effort to address what is, in fact, a very serious problem.

Questions? Comments? Ideas for race-neutral columns? I’m at singalminded@gmail.com or on Twitter at @jessesingal.

Image: Students protest outside the meeting of the University of California's Board of Regents in favor of Affirmative Action. The protests proved ultimately ineffective, partly because of pre-existing state voter initiatives. (Photo by David Butow/Corbis via Getty Images)

What’s really lacking is a willingness to admit that the reason Black kids aren’t getting admitted to top universities without racially discriminatory policies favoring them is that Black kids aren’t being prepared by the primary education system to be successful in top universities.

I mean maybe some “traditional” metrics for admission unfairly overlook some minority students. But grades and SAT scores and basic literacy really do predict college success, and Black students are lagging on these metrics. You can’t fix this by offering a slot at Harvard to an unprepared 17 year old - the damage of lousy education is done by that point. You’re just going to end up with students in over their heads among better prepared students racking up debt (and indeed Black students have much higher college dropout rates and higher average debt).

I can’t find it at the moment, but there was a study of UC outcomes post the 96 amendment that found that basically, the end of RBAA has significantly reduced Black admissions… but hadn’t changed Black graduation much at all. In other words, most of the students who were getting in “because of” RBAA were washing out.

The problem hasn’t been “anti-Black racism in college admissions” for half a century at this point, so explicitly pro-minority discrimination at college admission was never going to be more than a band aid.

Any serious proposal to improve minority outcomes in post-secondary education needs to start at correcting the abysmal performance of minority education at the primary and secondary levels. That’s a much harder but to crack, but the only one that’s going to work.

What a long, strange trip it's been, this reckoning with race these last 60-70 years. I remember when I became aware of RBAA in the early 1980's. I thought in those long ago times it (RBAA) made a lot of sense, even if most of the folks I worked with didn't agree. I'm not so sure it makes sense in 2022.

When someone suggests to me that no...in fact we've made little progress towards a less racist culture, I can't take them seriously....because I was there, all those long years ago.

It's a monster of a problem, complicated, painful, a real struggle, and results a mixed bag. but we're a work in progress, and I still have hopes for us.

I'll close with this: Loudly proclaiming that....if you don't agree with us or my ideas, you're a racist. Or casually claiming that millions of fellow citizens are Fascists!!! isn't helping the cause: It's offensive; it's insulting; and it's obnoxious. It not how to win friends and influence people.